|

|

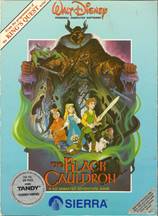

||||

|

Studio: |

Sierra

On-Line |

|||

|

Designer(s): |

Al

Lowe |

|||

|

Part of series: |

[stand-alone title] |

|||

|

Release: |

1986 |

|||

|

Main credits: |

Game design: Al Lowe, Roberta

Williams |

|||

|

Useful links: |

Complete

playthrough (91 mins.) |

|||

|

Unlike Sierra’s

better-known early AGI titles such as King’s

Quest 1-3, Space Quest 1-2, or Leisure Suit Larry In The Land Of The

Lounge Lizards, The Black Cauldron

is one of those games to which I have no nostalgic attachment whatsoever. As

an adventure designed specifically for children, it did not get much

promotion back in 1986, and I first played it probably already well into the

Internet age, as part of George’s Quest

to get acquainted with each and every one of Sierra’s adventure titles. It

was an interesting experience, however, in that I had never seen the Disney

movie on which it was based (or, for that matter, read the books on which the

Disney movie was based) — and found out that I was still able to form a mild

attachment to the game on its own, despite the understandable confusion with

its lore and internal logic. In spite of its shortness and simplicity, and in

spite of being more tightly restricted by its source material than any of

those other early Sierra games, The

Black Cauldron still preserves its own charm, though, admittedly, it is

much easier appreciated in the context of 1986 than any later year in video

game history. While at a certain point in

time following up a commercial blockbuster with one or more video games based

on its universe became a common practice — everything from James Bond to

Harry Potter has been sucked up by the interactive medium — back in the

mid-Eighties this was certainly not the case yet, and those few movie

franchises that did put out a tentacle into the world of digital gaming

usually remained contented with simple arcade products, e.g. Broderbund’s

early Star Wars games where you

just had to shoot up stuff. To the best of my knowledge, The Black Cauldron was not just a unique cooperation between

Sierra and Disney, but, in fact, the very first graphic adventure game to be

explicitly based on a movie (and, as it would turn out, Sierra’s first and

last such experience). This fact alone deserves that the game be at least

enshrined in a museum or something; but there’s actually quite a bit more to

be said! One reason why the game was

so quickly forgotten is that The Black

Cauldron itself — the animated movie, I mean — was received fairly poorly

in its time. Based upon Lloyd Alexander’s acclaimed fantasy series (Chronicles Of Prydain), it boasted

Disney’s hugest budget expenses to-date, featured the studio’s first use of

digital technologies, and had a generally darker tone than most of the stuff

from Disney’s post-war years; but either because of this latter circumstance,

or because the movie was gruesomely cut up by Jeffrey Katzenberg (in the

first of his many crimes against humanity), it flopped both critically and

commercially, and even today remains more of a cult favorite than a properly

revived survivor. Personally, I think that, with a few reservations, it’s

mostly fabulous — much darker and scarier indeed than anything from the

«Disney Renaissance» that followed Katzenberg’s arrival on the scene, not to

mention being one of the very few Disney movies without a single Disney song

in it (that alone should turn it into a sacred cow). But I guess this is not

quite what «family entertainment» was all about in 1985, certainly not for

those who’d previously feasted themselves on the likes of The Fox And The Hound. I am not sure if the Disney

people contacted Al Lowe because they were really thrilled with the idea of

turning a movie into a video game, or out of financial desperation — with the

studio losing money at a tremendous rate, they might have thought they could

at least cut some losses by lending its soul to a different body. In any

case, as Al himself

recollects, "they gave me

complete access to the original hand-painted backgrounds, the original Elmer

Bernstein score, even the original animation cells, which were still

literally lying in heaps, before being sent off to the dump!"

Amusingly, I also remember reading in some other interview with him which I

cannot locate at the moment that the Disney guys were apparently confused

when they learned that some of the player’s choices could result in

consequences different from the movie — the first documented case of a lack

of proper understanding between the «linear» and «non-linear» medium, if you

wish. Fortunately, Al was able to prove the rightness of his ways, or else

the game would have been nothing but a pale shadow of the cartoon. Unlike the other concurrent

Sierra games like King’s Quest and Space Quest, The Black Cauldron had one pre-attached condition: it was to be specifically

oriented at a young kids’ market, apparently including kids who still had

problems with writing (but not reading). This resulted in the game being

somewhat innovative (in its jettisoning the text parser), but also limited

its appeal — another reason why hardly anybody remembers it any more. It is

quite telling, actually, that Sierra never tested those waters again: after The Black Cauldron, its only

«toddler-specific» line of production was Roberta Williams’ Mixed-Up Mother Goose, while all of its

proper adventure titles, even including the «edutainment» line of Eco Quest and Pepper’s Adventures In Time, were clearly family-oriented and

could be enjoyed by kids and grown-ups on an almost equal level. There is no

doubt in my mind that The Black Cauldron

coould have been much better, had it not been designed with a specifically

pre-pubescent audience in mind — then again, I suppose Al Lowe himself

suffered so much from this restriction that he just had to promise to himself

that his next game would be

decidedly oriented at a post-pubescent

crowd. (For a good old culture shock, try beating The Black Cauldron and Leisure

Suit Larry In The Land Of The Lounge Lizards one after the other, then

come to terms with the fact they were written by the exact same person!). Anyway, I don’t even know

if the game managed to recoup its (tiny) budget. It blipped on the PC gaming

radar in a brief flash, then remained exclusively in the memory of a few 1986

kids and avid collectors. To this day, it’d be hard to find a proper review,

and it is not even available for sale on GOG — though, admittedly, it does

not have to be, since you can just download it for free off Al’s personal site. In the

review below, however, I shall briefly try to demonstrate that making it was

not a complete waste of time, and that even today it is quite possible for it

to provide you with half an hour’s worth of lightweight atmospheric fun —

particularly if you’re a 50-year old guy with a 12-year’s old heart inside. |

||||

|

Content evaluation |

||||

|

In general, The Black Cauldron sticks to the plot

of the Disney cartoon, which was, in turn, condensed from several volumes of

Lloyd Alexander’s Chronicles Of Pridain.

Playing as Taran, «Assistant Pig-Keeper» for the old enchanter Dallben, you

are supposed to employ the talents of your Oracular Pig, Hen Wen, to prevent

an evil wish-granting macGuffin (the Black Cauldron in question) from falling

into the hands of the Horned King — and, if it does, be ready to sacrifice

your own life in order to stop the cauldron from working its magic and

granting the King his own personal army of the undead. Along the way, you

meet many friends, such as the weird hungry creature Gurgi, the talentless

bard Fflewddur Fflam, fairies, elves, witches, and a plethora of beautiful

women, including Princess Eilonwy, to each of which you may hopelessly try to

lose your virginity... oops, wrong game. Once again, Al Lowe got me confused. Anyway, if you want to learn about the

actual plot in more detail, go see the movie and / or read the books. Since

it was clear that, by the standards of 1986, Sierra’s game would never even

begin to hope to match the beauty and the terror of Disney’s animated

visuals, Al cleverly decided to compensate in another direction — alternate

plot twists. Being able to solve the same puzzle in several different ways

was already a staple of Sierra games from as early as the first King’s Quest, but The Black Cauldron actually went further than that. From the very

beginning of the game, your quest could unwrap along completely different

trajectories — for instance, you could lose Hen Wen, the pig, to minions of

the Horned King and have to rescue her from the King’s castle (just as Taran

did in the movie), but you could also avoid

the henchmen and bring the pig safely to the proposed hideout, following two

not particularly complicated, but utterly different scenarios. The most important choices came at the

end of the game, where you could also follow the movie path if you so wanted

(Gurgi sacrifices himself for the sake of his friends and is later revived by

the witches), but could just as well trigger a much less uncomfortable ending

(by means of a magic mirror), or, on the contrary, a far creepier one (jump into

the cauldron yourself). There were also additional minor variations in your

final interaction with the witches, so, on the whole, the number of possible

different endings was formally huge — for a game that was supposed to be just

a light footnote to a Disney extravaganza. If only the game itself were a bit more

epic on the whole, this plot mechanics could have turned it into an early

masterpiece for Sierra. Unfortunately, in general there was simply not that

much to do. The entire playable area occupied about a third of the Kingdom of

Daventry (the Horned King’s Castle alone had about as many rooms as the

entire territory of Caer Dalben and its surrounding areas); dialog with most

of the characters was reduced to a small handful of lines of text; and there

was hardly any possibility to take a close look at any of the characters’

personalities. It is almost as if the thrill of «rewriting Disney history»

took over Al so much that he pretty much forgot to do anything else —

including his notorious sense of humor, of which there is not a single trace

anywhere. (Nor, for that matter, is any of the occasional humor in the movie

transferred over to the game — one could at least hope for a secondary

bumbling villain like Creeper to make a few gaffes, but I think the poor guy

doesn’t actually have even one line of dialog to his name). In the end, the game leaves behind an

odd impression. For a kid to play it after having seen the movie and be able

to explore the different endings must have been an interesting experience,

but just how many kids actually saw the movie and bought the game at the time? And for those who did not see

the movie (I only saw it after playing the game, for instance), how exciting

could it be to play a game which quickly introduced you to a whole bunch of

characters with weird Welsh names and unclear American purposes, then came to

an abrupt ending just when you were hoping to actually get to know at least

some of them better? Well... like I said, there’s about half an hour of

genuine intrigue here. |

||||

|

Given the game’s specific

age orientation, one should hardly expect a Monkey Island level of challenge, but that does not mean The Black Cauldron is just a breezy

walk in the park. In order to make the game «easier» for children, Al Lowe

introduced a revolutionary mechanic — he abandoned Sierra’s usual text

parser, which could theoretically make him, rather than Ron Gilbert of

LucasArts, into the father of point-and-click mechanics, except there was one

small impediment: in 1986, most PCs still had no mouse support, which meant

that any interaction with objects on the screen still had to be handled via

keyboard. The only solution was to have your character move as close as

possible to the required hotspot, then have him press one of the function

keys to interact with it (F8 to look, F6 to «operate»). The system is not difficult

to get used to in general, but figuring out specific details can be

frustrating. In a regular Sierra game around that time, for instance, when

coming upon a bridge across the river, you knew it always made sense to type

"look under the bridge"

even if the screen itself gave you no hint of anything valuable under it —

there could always be a payoff. In The

Black Cauldron, in order to look under the bridge you have to move into a

very specific position, wading into the water, and press F8. Considering that

most of the locations on the screen will give you a generic response, not a

lot of people — certainly not a lot of children — will even think about such

an option, and, consequently, will miss a very useful object which is not

crucial to winning the game, but can make your life a hell of a lot easier

throughout it. No surprise that the most

«complicated» puzzles in the game are the ones that require finding something

— like the hideout to where you are supposed to bring Hen Wen, or navigating

your way across the rocks at the foothills of the Horned King’s Castle. (All

this maze stuff is, of course, present in other Sierra games as well, but

here it is at the forefront just because everything else is so simple). The

actual object-based puzzles are mostly trivial; the most difficult thing is

arguably not to lock yourself out of the game’s best ending by rushing too

far ahead — ironically, those who would play the game after watching the movie are more liable to fall into that trap

than those who did not, and are therefore not intuitively motivated to

blindly follow the turns and twists of Disney’s plot. A few of the challenges

involve action-style mechanics — for instance, there is a primitive «combat

system» where you have to properly time your sword swing to knock out the

Horned King’s henchmen; a short climbing mini-game where you have to scale

the walls of the castle while avoiding falling boulders; and, of course,

plenty of agility requirements when you have to navigate your character

around tiny twisting paths over moats and precipices. I hate that shit in an

adventure game, and I suppose the kids who played it must have hated it as

well, but Sierra would not budge on its classic principles — whether you’re a

kid or an adult, death is a space of equal opportunity for all of us. An extra impediment is that

Taran actually needs to eat and drink every once in a while — a notable

innovation for Sierra, whose King Graham and Prince Alexander could easily

roam all over Daventry or Kolyma without the need to take a bite — however,

this quickly becomes an annoyance, particularly if you forgot to refill your

flask before infiltrating the Castle, where you can easily avoid all the evil

henchmen only to fall dead in the middle of your escape... from dehydration.

This is precisely the kind of cruel discipline that ultimately cost Sierra

its long-term reputation: people like to be disciplined with their video

games no more than they like to be in real life. Still, as far as 1986 goes,

the quality of the challenges is not that far behind the average King’s Quest (at least, the first two

games in the series; King’s Quest III

was already on another level). Beating the game is not challenging, but

beating it with the full score of 230 points without a walkthrough could take

a few tries even from a grown-up; and as for kids, I cannot state with

certainty that the elimination of the text parser actually makes things all

that easy — unless the kid in question does not know how to write (but they

still have to know how to read).

I’d actually say that the easiest aspect of the game is how short it is — I

guess that Al Lowe regarded the kids of 1986 as having the same IQ as

grown-ups, but a shorter attention span... which, come to think of it, may

not have been far from the truth. |

||||

|

Unfortunately, this is

where being based on a Disney movie — a good,

if thoroughly underrated Disney movie — really hurts the game. When it comes

to the Kingdom of Daventry, there is no single, direct prototype which it is

based upon, and so you can sort of regard it as a little CGA universe in

itself; the land of Prydain, however, is a straightforward projection from

the cartoon, and there was no way that the beauty and the terror of classic

Disney animation could even faintly be evoked in a video game around 1986

(Sierra would remember that dream, though, and come close to finally bringing

it to life with King’s Quest VII eight

years later). When your Horned King looks more like a roast chicken on two

legs and your three evil witches look like a 3-year old’s drawings, you gotta

have one hell of a power of imagination to compensate for the distance

between the game and the movie. Still, an interactive game

is an interactive game, and immersing yourself in the character always helps.

In designing the map, Al clearly relies on the experience of Roberta

Williams, who had already excelled in delimiting between the «safe» and the

«dangerous» zones of the Kingdom of Daventry, with subtle transitional

buffers in between. Here, too, you begin the game frolicking in the cozy,

cuddly green meadows of Caer Dallben, before the need to save Hen Wen or kick

the shit out of the Horned King brings you to the swampy and forested areas,

where it can be pretty unnerving to make your way through the evil-grinning

purple trees. Overall, the contrast between «safe» and «dangerous» zones

works here just as fine as it does in the old King’s Quest games — and for a game specifically designed for 10-year olds, I would say that the

level of scariness is just alright. I know I felt that familiar sense of relief each time I got out of the

forest / swamp and back to the green grass of Caer Dallben, and I played the

game while being at least twice as old as its recommended age! It is too bad that the

atmosphere could not be supported by meaningful dialogue; even though it

would have technically been quite possible to make the characters’

interaction a bit more sophisticated than it is, Al never goes beyond the

bare minimum, way below even the dialog in the movie, let alone the books. One

could suggest that it was specifically due to making the game accessible to

younger players, but the truth is that it actually has precisely the same

level of verbal sophistication as the King’s

Quest games, which were explicitly targeted to everybody. Indeed, such

was Sierra’s style at the time, and while Al would soon push those boundaries

forward a bit with the Larry games,

here he was perfectly happy to take Roberta as his role model in this area as

well. Alas, it’s just a bit difficult to form a «bond» with «your friend»

Gurgi, if pretty much the only thing you ever hear, er, read out of his mouth

is "Hi! I’m Gurgi. Do you have any

munchings and crunchings for me?" |

||||

|

Technical features |

||||

|

In terms of visuals, Black Cauldron is neither bad nor

outstanding for its time — the art is handled by Sierra’s chief early artist,

Mark Crowe, and is hardly all that different from his work on King’s Quest. In fact, the land of

Prydain looks very much like Daventry (or Kolyma), at least as far as the

«safe», green zones are concerned; for the «evil» zones, Mark chose a deep

purple palette which, along with the sickly green water in the moat around

the Castle, gives the Evil part of this world a slightly more psychedelic

flavor than anything he did for King’s

Quest. (Some of the assets, however, were blatantly recycled from that

franchise — for instance, the alligators in the moat were «borrowed» directly

from the moat around King Edward’s Castle at the beginning of King’s Quest I). And I may be wrong,

but I think that on the whole, there is a bit more of a concentrated attempt

to dazzle the young player with the dashing colors — check out the final

screen, for instance, where the heroes, echoing the finale of the movie, walk

into the sunset: dark and light green grass, blue mountains, purple flowers,

yellow-tinged clouds reflecting the setting sun (and they’re gliding across the screen!), and a mix

of blue and purple for the sky. This kind of «CGA scenery porn» can hardly be

found in any of the King’s Quest

games to that point. The smaller details,

unfortunately, remain as sketchy as always: for inevitable technical reasons,

sprite models of Taran as well as various NPCs bear not the slightest

resemblance to their prototypes in the movie, although at least Crowe had to

design a variety of new sprites (the Horned King, Creeper, Gurgi, Hen Wen,

the three witches, etc.) which had no direct precedent anywhere. And he does

try relatively hard — it is cute, for instance, how the sprite of Princess

Eilonwy looks just a little bit hunched, just the way she walks in the movie

(for that matter, she’s also strictly flat-chested, unlike, say, the sprite

of Princess Rosella in King’s Quest III),

or how funnily — and how fast — Gurgi waddles across the screen. These are

all, of course, just minute historical details, but it is instructive

sometimes to pay attention to all the subtle graphic tricks those early

artists and animators had to resort to in order to make those 320x200 pixel screens

come to life. |

||||

|

Okay, so this section will

inevitably be kept to a minimum. The entire game has but TWO very brief

musical themes, dutifully adapted for PC speaker from the original Elmer

Bernstein score (strangely enough, he is not actually credited in the game) —

one dark (the Horned King and the Cauldron!), one light (the green pastures

of Caer Dallben!), plus a few tinkly-dinkly sound effects here and there,

mostly recycled from other games as well. I suppose that Al himself must have

programmed the themes, being a musician and all, but given that, as he

himself recognizes, the studio was given full access to the complete score, I

feel he could have profited from it a bit more. That dark opening theme does

sound pretty decent when transposed from PC Speaker to MIDI, anyway. |

||||

|

Interface As I already mentioned in

the «Puzzles» section, the Black

Cauldron interface is pretty unique in Sierra history — this is,

essentially, a parser-based game whose parser skills have been cut off, much

like the tongue out of a mouth of an annoying blabberer. While I think it was

an interesting decision at the time, I am not even sure if it was really and sincerely caused by the desire to save the young and innocent

toddler from the need to learn how to spell the word ‘cauldron’, or if the

real reason behind it was that Al and his team were pressed for time and had

no desire to write even brief descriptions for the many objects on the screen

that the young and innocent toddler could be curious about. In any case, the

result was a system that could not have been anything but confusing for the

toddler. In this interface, you

«look» at things with F8 and «operate» on them with F6 — why F8 and F6?

Because F5 and F7 had traditionally been reserved for Saving and Restoring the

game in the Sierra engine. F1 is Help; F2 turns the sound on and off. What

about F3 and F4? These, even more confusingly, were reserved for «selecting»

an object from your inventory (F3) and «using» it (F4) on yourself (if it is

a food object, for instance) or your adversary (if it is a sword). So this

means that if the Horned King’s henchman approaches you and you have to cut

him down, instead of simply writing ‘hit guy with sword’, you have to press

F3, select the Sword from the newly opened inventory window, press Enter,

then wait until the henchman is in reach and press F4. Uh... okay. You can get used to it. The question is,

why should you? To add insult to

injury, there are three different

ways of handling your inventory — see a simple list of all the stuff you’re

carrying by pressing TAB; «see objects» by selecting this option from the

menu, where you can actually scroll through the same list and bring up small

pictures and descriptions of the objects; and the F3 «select object» command.

Poor young and innocent toddlers. In short, it does not take

a genius to see why this approach would not be adopted by Sierra for further

games, and why the elimination of the parser would have to wait until a

proper point-and-click interface would be elaborated four years later. Yet

there is still something to say about dead-end experiments like those — at

the very least, unlike a successful, well-tested and comfortable formula

repeated from game to game, they tend to stand out in memory (like the

much-maligned combat systems of the first Witcher

and Mass Effect games, abandoned

for their inconvenience to players but still remembered with a mix of hate

and curiosity for at least trying to be innovative). |

||||

|

Only a professional video game historian (that’s not me) or a

nostalgic fan of Sierra On-Line (that’s more like me) could ever bother these

days about replaying or even remembering The

Black Cauldron, yet this is not because it was a bad game — more because

its goals were so noticeably humbler than those of the titles surrounding it.

Short, highly derivative of both the movie it partially recreated and the

artistry of the far superior King’s Quest

titles, replacing the text parser with an even clunkier interface, and

explicitly oriented at younger audiences, it couldn’t even begin to hope to

compete with Sierra’s main lines of production at the time. I don’t think it

was ever included in any of Sierra’s anthologies, and even GoodOldGames does

not regard it as worthy of being sold for money (so Al Lowe just gives it

away for free), so why bother at all? Still, I don’t think it would be right to claim that the game does not

have its own «soul». Almost any product from the dawn of PC gaming has at

least a bit of it, and The Black Cauldron

is no exception. It was, after all,

one of the first attempts at transforming an animated movie into a video

game, a task that was taken seriously and with respect to the difference in

potential of the two types of media — all those branching paths and alternate

endings for which Al had to fight with the Disney people were very symbolic

of the opposition between «linear» and «choice-based» approaches to

storytelling in video games, and should necessarily be present in any

historical account of that struggle. With a slightly larger budget and a

little more respect, The Black Cauldron

could have easily beaten King’s Quest

in terms of lore, sympathetic characters, and plot tension; unfortunately,

neither Disney nor Sierra were wise enough to recognize this opportunity. |

||||