|

|

||||

|

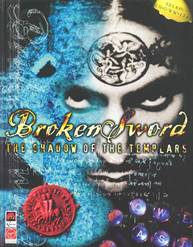

Studio: |

Revolution

Software |

|||

|

Designer(s): |

Charles

Cecil |

|||

|

Part of series: |

Broken

Sword |

|||

|

Release: |

September 30, 1996 (original) / March 21, 2009 (Director’s Cut) |

|||

|

Main credits: |

Producers: Charles Cecil, Chris Dudas, Steve Ince, Michael

Merren Writers: Charles Cecil, Dave Cummins,

Jonathan Howard Art: Eoghan Cahill, Neil Breen, Mike

Burgess Music: Barrington Pheloung |

|||

|

Useful links: |

Complete

playthrough (Director’s Cut; 9

parts, 574 mins.) |

|||

|

Once upon a time, there

used to exist an entire colorful industry of adventure-themed comic books, in

which all sorts of sympathetic, sprightly, somewhat naïve, and, well,

adventurous characters roamed the world to solve its many mysteries and

unravel its darkest conspiracies. This industry still exists, of course, but

it’s been a long time since it looked the way it looked in the

pre-post-modern era — simple and innocent, sometimes sadly tainted with the

vices of commonplace colonialism, Orientalism, and plain old racism, but just

as often offering its customers beginners’ lessons in how to fight all these

things. The genre was more European than American, since in the States the

chief emphasis had always rather been on crime-fighting superheroes, yet it

was loved all over the world, and even your humble servant remembers with

fondness his childhood hunt for all the volumes of Hergé’s Adventures of Tintin, which were

completely unavailable in the Soviet Union at the time. In the world of movies, the

single greatest tribute to those young and innocent days was arguably Lucas’

and Spielberg’s Indiana Jones — but

in the world of adventure games, somehow, despite the word «adventure» itself,

no such tribute really existed as late as the mid-1990s. Of course, there had been plenty of adventure games in

which your characters roamed the various corners of the world to unravel the

mysteries — in fact, LucasArts made two adventure games based on Indiana

Jones himself — but they did not really have the light, old-fashioned,

wide-eyed babe-in-the-woods attitude of one of those ye olde comic books like

Tintin In The Congo or something

like that. You could have your Roberta Williams fairy-tale, your Ron Gilbert

smarty-pants post-modern grin, some nice detective story or a spooky bit of

horror, but there was most definitely a niche waiting to be filled. In stepped Charles Cecil, a

young British game developer whose early childhood, somewhat ironically, had

been spent in the Congo (which his parents had to flee after Mobutu Sese

Seko’s coup in 1965). He and his company, Revolution Software, had already

made a name for themselves in the video industry with their two first games,

the fantasy tale Lure Of The Temptress

(1992) and the dystopian sci-fi adventure Beneath

A Steel Sky (1994). Yet neither of the two was good enough for Cecil to

become the love of his life (though he did return to sci-fi thematics with

the sequel, Beyond A Steel Sky, as

late as 2020). What he really

craved for was an Adventure game with a capital A — one that could immerse

the player in a colorful, old-fashioned, china-shop-meets-dark-alley universe

like Tintin’s, of which Cecil is a

self-acknowledged fan (and you could tell it in a flash just by playing the

game, without even reading any of his interviews). For his principal subject matter, Cecil

chose the Knights Templar — not exactly a fresh subject, but one that had

been recently refreshed thanks to Indiana

Jones And The Last Crusade, as well as properly fattened up with the 1982

publication of Holy Blood, Holy Grail,

the quintessential nonsense book to have inspired so many juicy works of art,

from The Da Vinci Code to Jane

Jensen’s third Gabriel Knight game. Charles Cecil, however, was there first,

though he barely scratched the surface of the intrigue — which, admittedly,

was more than enough for the genre he wanted to reflect in his game. For his principal location, Cecil chose

Paris — not so much the actual Paris of 1996 as the mythologized, idealistic

bourgeois Paris of French textbooks and, well, comic books — however, there

would naturally be multiple other locations in the game, since Adventure with

a capital A is quite impossible without lots of travel. Yet for the principal

character who would be doing most of the travel, Cecil preferred an American

rather than a Frenchman — either to make the game more marketable for an

American audience, or to make it more fun by means of the trusty «an American

in Paris» cliché, or, most probably, both. In any case, meet George

Stobbart ("two B’s and two T’s", in George’s own words), the

friendly and nosey American intellectual who would go on to star in no fewer

than five Broken Sword games and

become one of the most iconic protagonists in the history of story-based

video games (and a sixth one might well be in the works). The result was a smashing critical and

commercial success — Beneath A Steel

Sky had already established the reputation of Revolution Software as a

serious player, but Broken Sword: The

Shadow Of The Templars (for some reason, originally titled Circle Of Blood in the States)

singlehandedly put the company on the same level with such top competitors as

Sierra On-Line and LucasArts (both of whom it would actually manage to outlive

by playing it smart and avoiding risky business decisions). Reviewers praised

almost every aspect of the game, buyers were delighted, and for a brief while

it really seemed that point-and-click adventure games might have found a new,

highly promising direction, breaking up the solid, but already predictable

and somewhat obsolete formulae of the old giants. That hope did not last long

— in fact, much of it was extinguished already with the second game in the

series — but the reputation of Templars

has endured, and even today rare indeed would be a best-of adventure game

list that would forget to place it somewhere close to the highest ranks. I myself was very late to the party,

having mostly lost interest in adventure gaming with the demise of Sierra and

LucasArts, and did not pick up a copy until much later, already after Cecil

had revived the title with a special Director’s

Cut (in 2009), remastering the game for consoles and higher-end PCs,

redesigning its interface, and throwing in lots of additional sections,

primarily those in which you also have to play as Nico Collard, George’s

journalist sidekick and future love interest. My review will, therefore, be

centered around the special rather than the original edition, though I did at

least watch some gameplay of the original version to understand the main

differences; they will affect those

suffering from childhood nostalgia, but it is clear that if the game will

live on into the future, it is the Director’s

Cut that most people will be playing — and while I certainly do not think

that this is the best adventure game ever made, I have no doubt that it does

deserve to live on into the future. |

||||

|

Content evaluation |

||||

|

Just like one of them good old Tintin adventures, Shadow Of The Templars begins relatively

low-key — as a murder mystery (a double murder mystery in the Director’s Cut, with Nico Collard

witnessing the shooting of one character and George Stobbart accidentally

caught up in an explosion causing the death of another), which gradually

escalates into something far more complex and sprawling, ultimately revealing

a megalomaniacal plot to take over the world which George and Nico have no

choice but to stop in its tracks. The plot will take both of them all across

the posh and the slummy areas of Paris, as well as across the border to

Ireland, Spain, Scotland, and even a remote village in Syria, where they

shall meet all sorts of colorful characters, uncover enough mystical secrets

to fill up an encyclopedia, risk their lives on countless occasions, and (in

the case of Nico) even have the opportunity to reassess their family history. Let me get this out of the way first

and foremost, though: the plot of

the game — and this applies even more strongly to all of its sequels — is

fundamentally crappy, and I have no doubt that Charles Cecil himself is well

aware of that. I am not even going to waste space and time on going into

details (just play the game or consult Wikipedia): all those Neo-Templar

cults, idols of Baphomet, murders, burglaries, and conspiracies largely just

recycle old pulpy clichés which were hardly brilliant in the first

place. Even some of the Tintin

adventures, with Hergé at his best, could have more character, soul,

and invention to their plots than Cecil, to whom the story in these games

always takes third, if not thirty-third, place to everything else. Nor does the author give much of a damn

to historical depth. Apparently, Cecil did travel to Paris and conduct some research

on the Templars, but whatever he may have learned was not integrated too

seriously in the game. All we need to know, ultimately, about the Templars,

is that they’d discovered a MacGuffin, and that their modern day followers

are looking for the MacGuffin to help them rule the world. If you want a game

that attempted to take the Templar lore with a bit of actual respect, look no

further than Gabriel Knight 3; this

game approaches the subject with about as much delicacy as Hergé

approached the topic of the Soviet Union in his Tintin Au Pays Des Soviets at the earliest stages of his career. Arguably the only general strength of

the plot lies in its amazing diversity, almost unprecedented for an adventure

game of its time. Already the Paris section swiftly moves its characters from

the gaudiest locations of the city to regular «bourgeois» living quarters and

from there, to dirty and unpleasant sewers — or to places where funny and

unexpected culture clashes take place, such as George’s encounter with an

aristocratic British lady who helps him overcome the stuffiness of a typically

French clerk ("an Anglo-American alliance that actually worked!",

in Lady Piermont’s own words). Less than midway through the game, George is

whisked away to Ireland, where you have to help him sort things out with the

everyday customers of a classic pub; from there, we are taken away to a

lively market in Syria, then to a remote mansion in Spain, and then, finally,

to a rundown stone castle in the depths of Scotland. Ultimately, there is just so much

happening that you actually have to step back a bit and assess the general

picture to understand that none of what you see makes much sense, that none

of the characters may be taken seriously (at least, not as far as they are

related to the main story), and that there is nothing genuinely outstanding about

any of the twists and turns that the plot takes along the way. But if you

thought that Charles Cecil himself might take offense at you for feeling this

way, the ending of the game, hopefully, will reassure you of the opposite.

Once you get to the final climactic denouement, it is over in less than five

minutes (perhaps a bit more, depending on how much time it takes you to crack

the final puzzle), as abruptly as things typically come to an end in a

Hitchcock movie — and subsequent games would make this even more obvious,

totally cutting out any farewell scenes or epilogues, to save you from the

danger of taking the time to read something much more than necessary into the

story. It was all about the suspense, the action, the intrigue, the

characters, the atmosphere, and, in Cecil’s case, the puzzles — it was never

about «what is the philosophical significance of what just happened?» (Of

course, you can discuss the

philosophy of Hitchcock, but it is found in the personalities of the characters rather than in their actions). As frustrating and disappointing as

this shallowness might come across, there are certain angles from which Cecil

could even be commended for making such a light-headed, simple-and-stupid

game precisely at the time when adventure games, armed with recent

technological advances, seemed to be taking a sharp turn towards depth and

maturity — Cecil, on the other hand, made use of exactly the same

technological advances (graphics, sound, voice acting) to create an

unabashedly retro experience, practically a love letter to those strange

times when the grass was greener and complex issues could be handled

simplistically without anybody complaining. What is even more admirable is

how the man, with the tenacity of a veteran bulldog, managed to carry that

aesthetics almost unchanged through the next two decades, sticking to his

guns through thick and thin the same way Angus Young sticks to his school

uniform. Curiously, The Director’s Cut, in its introduction of Nico as a playable character,

did seem to try and make a very small step in the direction of giving more

depth and sense to the plot and at least one of its heroes. Unlike George,

who is mostly all about solving the mystery and staying alive, Nico is shown

as somebody deeply concerned over her family history, shocked by the awful

revelations about her own father, disturbed by at least some aspects of the

murders and betrayals going on around her, and tends, on the whole, to behave

more like an actual human being than a completely conjectural, cartoonish

character. On their own, these additions work reasonably well — but there is

a huge dissonance between them and the rest of the game, not to mention

Nico’s personality in subsequent games, which displays none of the

psychological complexity of the Director’s

Cut additions (unsurprisingly, since all but one of these subsequent

games were produced before, not after the Director’s

Cut). It is, therefore, not surprising that not all veteran fans, judging

by their Web reactions, were all that fond of the additions. Imagine James

Bond, after disposing of yet another of his SPECTRE enemies, substituting the

expected one-liner for "was it worth the tears of a tortured

child?" (Better yet, don’t

imagine it, or you might end up in the director’s seat). It is not, of course, as if the typical

adventure game of the 20th century was generally distinguished by a masterful

and meaningful plot — but I do wish to emphasize just how much Shadow Of The Templars went against

the grain of the time, taking a sharp turn into the oncoming lane with its

retro aesthetics. The fact that it went on to achieve such unexpected success

should, by itself, be inspirational to all who want to make their personal

mark upon the world but are too afraid of not finding their audiences and end

up latching on to current trends and losing their identity. And, of course,

the personality of Shadow Of The

Templars has nothing to do with its story — it is all about its

atmosphere, which we will get around to shortly. |

||||

|

Shadow

Of The Templars did

not revolutionize the established puzzle mechanic models of the

point-and-click adventure game, but it did put its own subtle twist on them.

First, unlike the typical Sierra and LucasArts game in which actual puzzles

(logic puzzles, construction puzzles, mazes, etc.) were always extremely

limited as compared to situational challenges, solvable through dialog and

object manipulation, Shadow

explicitly acknowledges such puzzles as being more or less on par with

everything else. The game is not exactly Myst,

but you will have to spend lots of

time wrecking your brain over grotesquely complicated locking systems,

linguistic codes, chessboards, and optical phenomena to get where you’re

going, and if you are a seasoned adventurer who tends to think of such things

as nuisances, not fun, Shadow Of The

Templars, as well as all of its successors, are definitely not for you. Of course, in a game that tries to

follow in the footsteps of Tintin

and Indiana Jones, franchises that

more or less assume that the entire world population is split into two halves

— our ancestors, who design insanely complex traps for future generations,

and future generations that try to show themselves worthy of the mighty

intellect of their ancestors — in such a game, logic puzzles are to be

expected as the norm. I remember almost rage-quitting at being unable to

crack the very first one in The

Director’s Cut (where Nico has to dismantle two locks which some Parisian

dumbass has constructed as tricky sliding puzzles), but from a reasonably

impartial standpoint, most of these puzzles seem to be fair — at least, to

the player who knows a thing or two about them and is not mathematically /

geometrically challenged, like I am — on the other side, with my linguistic

background and all, I quite enjoy the code-breaking puzzles, which may well

be a thorn in somebody else’s backside. That

is actually the treacherous circumstance: in his admirable attempt to make

the puzzles as diverse as possible, Cecil made sure that there will most

probably be at least one or two moments of absolute impasse for any given

group of players. Oh well, at least we know that the Internet is for

walkthroughs. The «regular» puzzles are not too

difficult; apart from the usual necessity to pick up everything that is not

nailed down and manipulate your inventory to find the right solution, success

frequently depends on talking to the correct character at the correct time to

receive the right cue, and, occasionally, on proper timing. It was, of

course, the latter that was responsible for the infamous «Goat Puzzle», which

allegedly cost the nerves of miriads of adventure gamers back in 1996, when

Internet walkthroughs were hard to come by — a challenge based on properly

timing your way out of a tricky situation. (For The Director’s Cut,

Cecil simplified that puzzle to the point of making it trivial — which was

doubly silly, since /a/ by that time, anybody could look up the solution on

the Web and /b/ he could have at least replaced it by something more logical,

yet still worthy of a challenge). But in reality, what makes the Goat Puzzle

so difficult is precisely the fact that the other puzzles are generally quite trivial in comparison; since

you do not have to bother about timing your actions right until your meeting

with the goat, it catches you unawares and messes you up. That said, trivial or not, nobody could

deny that Cecil really makes you work for your money (literally). While about

half of the game will have you simply talking to its characters, the other

half will be all about thinking your way out of situations — and in most

cases, the challenge will amount to much more than just picking up an object

in one location and giving it to another character in another location. Most

of your tasks — how to get into Khan’s room at the hotel? how to get money to

pay the Syrian driver? how to break through to the ailing witness in the

hospital? — can only be solved in several stages, at least one of which will

not be logically obvious in the least («bad design», some will say, but

that’s debatable — if all the puzzles were always logically obvious, what

would be the challenge in that?). In the modern world, I just do not see how

anybody could be patient enough to get through it all without a walkthrough,

but hey, that’s classic adventure gaming for you. At least Cecil loyally follows the

LucasArts formula — there are very few situations when you can die in the

game (and you are immediately revived anyway), and no situations where you

could get deadlocked because you forgot to pick up an object in Ireland that

you needed in order to solve a puzzle in Syria, or something like that.

However, there are also no multiple paths or solutions — other than a few red

herrings here and there (don’t forget to give the demon statue at the end of

the game a smoking pipe, for a laugh), your trajectory should be quite

straightforward, meaning no real replay value. Occasionally, you get to make

a choice in one of your conversations, but these are included just for a bit

of atmosphere (as they are in LucasArts games), and even when one choice is

obviously «right» and the other just as obviously «wrong» — for instance,

letting the restaurant waitress drink alcohol after the explosion knocks her

out, while refusing her a drink leads to you getting some extra information —

making the «wrong» choice never penalizes you too seriously (the waitress

does not know anything particularly important anyway). Overall, the puzzles are more or less

what you’d expect from a game that takes Tintin

as its ideal — browse through the early volumes of Hergé’s works and

you will find out that the young Belgian reporter used more or less similar

(and sometimes, similarly ridiculous) tricks to get himself out of difficult

situations, except that he did not have to solve goddamn sliding puzzles in

real time. |

||||

|

Oh yes, baby. Broken

Sword: Shadow Of The Templars is not really a game about the Templars. It

does not teach you any significant moral lessons (other than that of staying

away from short-tempered goats). It will probably not make you love sliding

puzzles and chess compositions more than you already do (or do not). But if

it does not enchant you with the shapes, colors, manners, and speech patois

of its universe, it is then and only then that you will know it has truly

missed its mark — although, admittedly, I can very well understand how a

typically 21st century mindset might be wired to sweep all of that aesthetics

under the carpet, given its decidedly pre-1960s flavor. Although, to the best of my

understanding, the game is set to take place in modern times, the only things

about it that look «modern» are the occasional hi-tech gadget, the occasional

hi-tech vehicle, and the occasional jet plane. Cecil’s Paris is by no means

the Paris of 1996 — it is the Paris of Hergé’s Tintin from, say, the

1940s or the 1950s, and with strong echoes of an even earlier Paris, the

legendary mythical imperial Paris of Napoleon the Third or something like

that; at least, 90% of the architecture you see around you comes from the

times of Baron Haussmann — and since there is not a lot of traffic in the

game to impede your progress, you might as well use your imagination to draw

in a bunch of horse carriages to complete the picture. The people usually match the place —

police officers, such as the comedic Sergant Moue, walk around dressed like

pre-World War I gendarmes; Inspector Rosso (sic!) wears a classic trench coat and probably comes right out of

a Georges Simenon novel; representatives of the working class are all

middle-aged, grumbly, sarcastic, and heavily mustached; clowns and jugglers

provide street entertainment for children and parents alike; and, of course, Paris

is presented as a land of absolute racial purity, with every last store clerk

and ditch digger looking like the proud descendants of ten generations of

proud Norman farmers. Absolutely the same concerns every

other place in the game as well. Ireland is, of course, the place of

funny-talking stout little ale drinkers, gruff, burly, suspicious of

strangers, but potentially friendly if you can find the right touch. Syria is

one huge colonial bazaar, half of it occupied by stupid Western tourists and

the other half by crafty local entrepreneurs making money off stupid Western

tourists. Spain is the slowly dying territory of obsolete aristocratic legacy

— probably just what Paris would become without all the tourists to keep it

alive. And Scotland is the land of slightly more helpful and less stuffy Celts

than Ireland, green hills, and lonesome deserted castles that harbor

terrifying secrets. All of this could be very offensive —

and I have no doubt that, to many people, it is — if it were taken just a tad

more seriously than it is. But it is absolutely impossible to mistake the

fantasy world of Broken Sword for

something even remotely reminiscent of the real universe; it is no more

realistic, in fact, than the world of The

Witcher or even The Lord Of The

Rings, just as the world of Tintin

was not realistic when Hergé painted it on the pages of Le Petit Vingtième. Nor is

there any realism in the game’s caricaturesque villains — and even its

sympathetic figures are odd concoctions of a unique imagination. Naturally, this does not mean that

characters in the game are not relatable, or that their personalities and

their sense of humor cannot be connected to our own issues in this here day

and age — on the contrary, precisely the fact that Cecil allows himself to be

completely free of realistic conventions and go whenever he wishes to go is

responsible for most of the game’s atmosphere. When playing the game, by no

means should you be tempted to hurry it up and miss all the optional

conversations with ordinary people on the streets — this is what gives the

game most of its character, and this is usually where most of the hilarious

jokes are buried, too. (George: "I’d

be glad to talk with the Inspector, but I don’t want him working his psycho

weirdness on me". Sergeant Moue: "Ah, no, m’sieur. You are confusing the science of parapsychology with

witchcraft." George: "Oh

yeah? What’s the difference?" Sergeant Moue: "We don’t do sacrifices".) Arguably the most memorable NPC in the

game is Nejo, the Syrian street vendor boy who, instead of a country bumpkin,

unexpectedly turns out to be quite smart, sarcastic, and extremely well

educated in Anglo-American pop culture (even having learned his English from

tapes of Jeeves And Wooster),

meaning that the word «Templar», for him, is most closely associated with

works by Leslie Charteris. He is still a little stereotypical, a bit of a

cross between Disney’s Aladdin and the Artful Dodger, but his entire schtick

is symbolic of Cecil’s constant struggle to transcend stereotypes and

surprise the player with unpredictable personality features — a struggle in

which his failure-to-success ratio is about 50/50, but Nejo is his crowning

achievement in this line of work. If there is one thing in which Cecil’s work

is, after all, more modern than that of Hergé’s, it is in the sphere

of wittier and more educated dialog. (Nejo does have the honor, after all, of

posing the most brilliant question in the game — "What good is a Picasso, sir, if you cannot bounce it off a wall?") Much, if not most, of the game’s humor

is based on culture clashes: although the character of George Stobbart

certainly transcends the stereotype of the «uncultured American tourist», his

simply being American already activates the image in the minds of everybody

who he comes across (George: "Don’t

shoot! I’m innocent! I’m an American!" – Sergeant Moue: "Can’t make up your mind, huh?"),

and the poor guy has to carry that cross all the way until Syria, where he

finally is relieved of his burden by a couple of genuine uncultured American tourists (the ultra-annoying Duane and

Pearl Henderson, cursed with subsequent appearances in every single Broken Sword game). Meanwhile, Nico

has to carry the cross of posing as the French Femme Fatale, as deadly as she

is beautiful and all that, though most of the time she only gets to inflict

her beauty and deadliness (deadly humor, that is) on George (even in The Director’s Cut, her added parts

are mostly solitary). If there is one glaring flaw in Cecil’s

universe, it is the inability of its characters to engage with credibility

and heart in any sort of romantic scenarios. Admittedly, this, too, may be

inherited from Tintin (whose hero

was always notoriously asexual), but we are definitely introduced to the idea

that there is something between

George and Nico (there is even a third component in this triangle, an

obnoxious Templar scholar called André Lobineau, who keeps inserting

himself between the two lovebirds with the subtle insistence of an 18-year

old street thug) — yet Cecil is too afraid that any realistic romance will

break up our immersion into his fantasy world of old-fashioned irony, so

anything explicit is limited to a brief kiss at the end of the game, and (only

in The Director’s Cut) a final

picture of our heroes atop the Eiffel Tower (I mean, where else would a

Parisian journalist celebrate her affair with an American tourist?). The relationship between George and

Nico certainly brings to mind a similar cat-and-mouse relationship between

another famous adventure game couple — Gabriel Knight and Grace Nakimura — but

even though in Cecil’s universe the two actually do become lovers, unlike Gabriel and Grace (whose embarrassing

one-night stand in the third game ended in tragedy), it is unlikely that you

will ever feel a thing for the couple, whose union is more of an artificially

arranged engagement than a natural affair. Romance in Broken Sword is usually handled with the same old-fashioned irony

as anything else, which begs for the question of whether it wouldn’t have

been better to leave it out altogether. I mean, there is absolutely no need for George and Nico to develop

any feelings for one another — but perhaps Cecil thought that future fans

would crucify him if he did not make them do it, so he did make them do it.

Not that it’s a huge criticism or anything: the entire romantic line in the

game takes up maybe 1% of it. Nothing fatal. Ultimately, Broken Sword is all about the little things. One aspect of the

game that most players are not likely to explore is the option to try out all

your objects on all the NPCs with whom you are able to converse — in the Director’s Cut, this is made

convenient by having all of your inventory arranged as potential topics of

dialog (if a particular object has already been used up, it is shown blotted

out). The absolute majority of the resulting conversations are completely

unnecessary for progressing in the game, but it is often within them that you

will see concealed the most hilarious, most absurdist, most ironic, and most

dark-humored bits in the game. Show the Clown’s Nose to the stern Eastern

European professor, for instance, and he will tell you that "in my country, we have no use for

clowns... they were dealt with most severely in the last cultural cleansing"

(George: "What about the mimes?

Did you get them too?" Professor: "All gone. Our streets are mime free." George: "It sounds like heaven..."). Thus,

in one absolutely irrelevant exchange you get (a) an "I hate clowns and

mimes" joke, which is always nice to have if you hate clowns and mimes

(and you should), (b) a subtle reminder about the totalitarian practices of

the Eastern block (never mind that the game takes place in 1996 — remember,

it is an alternate universe in which Woodstock, Watergate, and the fall of

the Berlin Wall never really took place), and (c) who knows, maybe even a slight

jab at progressivism (embodied by George) which is so often ready to align

itself with totalitarianism whenever their interests intersect? Okay, (c)

might be taking things too far, but it’s still amusing that this silly bit of

dialog took my train of thought to that place. I do realize that a game whose primary

(or, at least, one of the primary) selling points is the ability to have

diverse conversations about drain cover lifting tools and to try out your

shiny electric buzzer on the hands of everybody in the neighborhood (not that

they ever fall for that, the bastards) may

be questionable as to whether it can have any lasting impact or replay value.

So do not take my word for it — if you have not done so already, just play it

for yourself, and see if the combined magic of a brightly colored idealistic

reflection of our planet imposed upon a lifting key as used by Parisian sewer

workers convinces you that Broken Sword

opens up a special path to perceiving the meaning of life... or maybe not. |

||||

|

Technical features |

||||

|

If you are creating a

dollhouse universe in the style of Tintin,

you’d better make sure that your visual art be up to par — otherwise, people

might not even catch on to the game’s legacy. Fortunately, by 1996 this was

technically possible. In terms of graphic resolution, Shadow Of The Templars was a huge improvement over Revolution’s

previous game, Beneath A Steel Sky

(640x480 vs. the latter’s 320x200), and while de-pixelation and upscaling in The Director’s Cut made it look even

better, I must say that I have few qualms about the way the original looked;

640x480 can work wonders for 2D comic-cartoon style, and it actually did for

both of the first two games in the series. (Then they switched to 3D, and

everything began to suck, but let us not get too far ahead). More precisely,

the resolution gives you exactly

the kind of detalisation you need to match the spirit of a colorful Belgian

comic book circa 1950 — anything less and you’re digitally screwed, anything

more and you begin going for extra realism which you don’t really need. Cecil’s art team did a fantastic job

bringing to life his idealistic fantasies. The bright colors of an autumnal

Paris, all brown and red and sepia; the lush green of Ireland and Scotland;

the yellow sands of the Syrian desert — the game is visually resplendent in a

way that no Sierra or LucasArts had a proper chance to be. The level of

detail is incredible — the leaves, the cracks in the pavement, the small

blemishes in old wall paint, the chimney smoke, the rich interiors in

Parisian luxury apartments and ethnographic museums, the overturned chairs

and broken lamps after the cafe explosion, everything looks like it was drawn

straight from the heart, making the fantasy world fully believable and well

worth escaping into, rather than from. The cartoonish characters are also

rendered sympathetically; higher resolution allows them to have changing

animated facial expressions and realistic walks across the screen, as well as

be scalable depending on their distance from the player. George is a dashing

young fellow (though, strangely enough, a bit hunchbacked) looking precisely

like an intelligent American

tourist should; meanwhile, Nico has the smoothest and sexiest walk of any

female protagonist in an adventure game up to that time (and much later, for

that matter, since most adventure games would very soon be in 3D, and it

would take a looooong time before

3D characters in adventure games would begin walking without suffering from

quantum disorder). One significant difference between the

original version and The Director’s Cut

concerns the fate of close-ups. In the original game, large images of

characters were only present during occasional phone conversations, when

George and his phone partner would loom over the entire screen; otherwise,

conversation would simply be illustrated with large subtitles over the

characters’ heads. In The Director’s

Cut, every time you strike up a dialog with somebody, you get small

cut-out profiles of the characters near the top of the screen, allowing you

to closely scrutinize their facial expressions — strange enough, the profiles

are not animated (was there not enough budget to make them move their

mouths?). However, phone conversations, like everything else, are also now

represented by cut-out profiles rather than full-screen images, which, I

think, was a mistake — there’s no reason we can never look at a full-screen

George Stobbart. Some of the game’s most climactic

events are transferred to animated cutscenes — a limited number of cartoon

videos with predictably low quality (unfortunately, they were not properly

remastered for The Director’s Cut)

which still do a good job of more closely familiarizing us with the principal

characters, as well as bring in bits of speedy and turbulent action, making

the generally static game more lively. The

Director’s Cut throws in even more of these, particularly in Nico’s

opening segment and during the ending (where we have that tacky romantic

scene with Nico and George atop the Eiffel Tower), but while they are

definitely more hi-res, they also look surprisingly more stiff and

comic-bookish than the little animated sequences designed by the original

team (this is probably the biggest stylistic incongruence between the

original game and the new edition). Overall, I think it would not be much

of an exaggeration to state that Shadow

Of The Templars is simply one of the most beautiful, most lovingly

crafted 2D adventure games of all time. The uniqueness of its art logically

stems from the uniqueness of the combination of its components — the

«mythical realism» of Ye Olde Dear Europe as represented by a classic comic

book drawing style in relatively high resolution. Other games would give you

one or the other part of this ensemble, but never all of it at once. I mean —

where else have you seen Paris pictured quite like that? Nowhere, that’s where. |

||||

|

For all the beauty of Shadow’s visuals, there was

surprisingly little work done on the music soundtrack. You would probably

think that a representation of semi-mythical quasi-1950s Paris would scream for some Edith Piaf or, at

least, some instrumental cabaret music; but, apparently, authentic French

music was too expensive to license, and nobody at Revolution Software could

compose French music in the first place. The hired composer for this game was

Australian-born Barrington Pheloung, whose chief claim to fame was incidental

music to the British detective series Inspector

Morse; for Broken Sword, most

of the music was quite incidental, as well, as the themes are usually

delivered in short, concentrated bursts at the beginning of the scene, and

then tend to be replayed after a carefully measured out period of silence. I certainly do not hold the

opinion that, with the arrival of proper sound cards, all games should have

music playing at all times — honestly, both adventure games and RPGs that do

that often tend to get on your nerves, replaying the same theme over and over

while you are stuck over a puzzle. So there is nothing wrong with much of Broken Sword taking place in relative

silence, with only marginal sound effects like chirping birds and whistling

wind accompanying the action (or lack of it). The problem is, some interesting, evocative, and

memorable music themes would be nice to have, and there are none. Pretty much

everything that plays out is just sweet background phonation, usually

orchestrated. Even the Syrian themes do not sound particularly mid-Eastern,

and the Irish flavor is only represented by an annoying fiddle part churned

out by a fiddler in the pub. The Director’s Cut fares even worse in this respect: for some of the new segments,

as well as Nico’s radio station at her apartment and the final titles,

Revolution contracted the services of jazz guitarist Miles Gilderdale and

young soul vocalist Jade Herbert. While both of them are obviously competent

(though nothing too special to my ears), this new music does not

stylistically fit in with the rest of the game at all — it is so immersion-breaking that I’d rather turn the

sound off altogether (fortunately, nobody is obliging you to turn on that

radio, and those final credits... who watches them anyway?). If the music in general is

a disappointment, the voice cast certainly is not, though, again, unlike the

graphic art, it is not outstanding. George is voiced by Rolf Saxon, a TV and stage

actor whose role in all five Broken

Sword games still remains his chief claim to fame; Saxon brings in just

the right amount of effort to make his Stobbart a little ironic, a little

naïve, a tad cynical and a tad idealistic — more or less the same

psychotype as Tintin, except that George is also a bit more attracted by the

opposite sex. Nico, who, unfortunately, did not have the luxury of being

voiced by the same actress throughout the game, is here represented by Hazel

Ellerby, to whom falls the task of also making her both cynical and

idealistic at the same time while always maintaining a heavy French accent —

a job that she does reasonably well. Most of the other actors do

a solid job as well, although they usually just latch onto the assigned

stereotypes, delivering the required combinations of French / Irish / Spanish

etc. accents with specific emotional states — the police inspector has to be

Suspicious about everything, the British lady has to be Victorian-Eccentric,

the East European professor has to be Stern, the Syrian driver has to be

Eastern-Suave etc. I do not remember any specific voice part that would

really stand out or defy expectations... well, maybe Fleur, the clairvoyant

lady selling flowers and telling fortunes next to Nico’s doorstep, does a

slightly more subtle and creepy job than the rest (she is voiced by Rachel

Atkins, whom most people now probably know as Dolores Umbridge from the Harry Potter movies). But on the

whole, this is precisely what you should be getting — all of these characters

were conceived as fixed stereotypes, and trying to give them Shakesperian

depth would inevitably lead to failure. |

||||

|

Interface Although the gameplay

mechanics of Broken Sword do not

exactly shatter the foundational principles of point-and-click adventures,

Cecil clearly took some time aside to think about design. For the standard

playing mode, he chose the two-option mode — in the original game, you could

switch between «Look» and «Pick up / Operate» options, while in The Director’s Cut you just have a

single-shaped mouse cursor hovering over the object, which you can click on

with the left mouse button to «Operate» it or with the right mouse button to

get a description of it (this actually took me a bit of time to discover

without reading the instructions — for the first hour of the game, I was

stupidly not even aware that I could «Look» at anything, despite the cursor

icon consisting of two parts, a moving «Cogwheel» for operations and a

blinking «Eye» for inspection). This certainly limits your playing options,

but at least it’s a little better than Sierra’s option-less programming of

the mouse cursor for most of its games since King’s Quest VII. Somewhat more innovative is the dialog

system, which is cleverly integrated with your inventory window — after the

initial conversation with the nearby NPC is over, you are given a list of

potential topics for discussion, all of them represented by icons rather than

words (arranged in a row at the top of the screen in the original game, and

in a special pop-up window in the remake). Already explored topics are either

shaded out or removed to save you from clicking on them again. Somewhat

confusing is the fact that some topics can actually be explored twice or even

thrice, but in order to do that you have to close the window and strike the

conversation up again, which some players may probably forget to do

(admittedly, most of these second-time options are laconic and optional). This design is certainly more

convenient than, for instance, a typical Sierra game like Gabriel Knight, where, in order to get

an opinion on or a reaction to any object from your inventory, you had to

open the inventory window, select the object, close the window, click the

object on the NPC, then rinse and repeat for all other items in your

inventory without knowing which ones are bound to trigger a generic "you

can’t do that" response and which ones will be significant or at least

hilarious. On the other hand, you could certainly argue that this makes the

game more predictable and less challenging. God be your judge in the matter. The mechanics for solving the game’s

tile, code, and other such puzzles are pretty self-explanatory and need no

comment — if you like these puzzles, you won’t be frustrated by their

implementation, and if you do not, no amount of smooth mouse control will

save the day. Saving and restoring is pretty easy and commonly available,

though the amount of save slots is limited (which is not a big problem

anyway, considering that you cannot get hopelessly stuck or hopelessly dead).

And since all the locations in the game are conveniently chopped up into

small clusters, joined by an insta-travel map, you won’t ever have to worry

about tedious backtracking upon forgetting to pick something from somewhere.

In short, Charles Cecil takes real good care of his customers! Apparently, The Director’s Cut takes even more care of its customers with an

integrated hint system which, honestly, I never used (whenever I do get

stuck, I just find a walkthrough — yes, I’m totally a renegade these days

when it comes to adventure gaming). There are other subtle ways as well in

which it simplifies the game (you can find many a grumble from old veterans

of the series on the Web), but I still cannot bring myself to openly

recommend the original over the remake — not that you are ever forced to make

a choice, since most places where you can buy the game today offer both

versions bundled together, with the original as a free bonus. |

||||

|

Although, as I have already pointed out, Shadow Of The Templars has pretty much become an unshakable part

of the gaming canon (no list of best-of adventure games of all time ever

dares to cut it out), surprisingly few people go to the trouble of trying to

explain what precisely it is about the game that makes it so endearing. The

cartoon art? The jokes? The tile puzzles? The, uh, adventure? We do have

hundreds of marketed titles that do all that, don’t we? Almost nobody points

out the aesthetics of the game as

its chief selling point — maybe, at least in part, because delving in deep

discussions of the game’s aesthetics can actually lead you out into somewhat

dangerous waters. Yet, want it or not, this game is all about aesthetics —

take Cecil’s imaginary, mythical, pre-modern take on the universe out of the

game, and you are left with a painfully average, clichéd, predictable

mystery whose only intrigue will come from purely mechanical puzzle solving. Even

when it was originally released, back in 1996, the game was not so much

behind its time or ahead of its time as it was out of its time — which is, kinda sorta, the precise thing that

unites it with Gabriel Knight, whose

author (Jane Jensen) has a lot in common with Charles Cecil, despite the many

formal and official differences between George Stobbart and the

Schattenjäger. Gabriel Knight

is a game steeped in tragedy; Broken

Sword is a comedic series. Gabriel

Knight wants you to care about its characters; Broken Sword wants you to admire the stylish coolness of its

characters. Both series, however, want to place you straight in the middle of

an alternate version of our universe — a little brighter, cleaner, and more

old-fashioned on the surface, but also a little darker and more mysterious on

the underside, dealing with the timeless battle of good against evil that is

only tangentially related to modern events. It

would not be right to state that Cecil does not at all want you to take his

universe seriously, though — it’s just that any of the depth in this game has

to be uncovered from its witty jokes, once you separate them from the chaff

of the corny ones. Shadow Of The

Templars boasts a level of sharpness that Cecil would never be able to

repeat — in fact, most of the subsequent games in the series feel more like

reflections of impressions from their average players and reviewers rather

than reflections of the same vision that the series’ creator had in store for

the first and best title. Lightweight as it is, there are many, many points

in the game that might make you want to stop and think, and find much tighter

parallels between this imaginary existence and the actual world we live in

than you thought there were at first. And it is for these parallels, not for

the goat challenge or the sliding tile puzzles, that the game is truly

replayable in our time, or, presumably, any time that might follow. |

||||