|

The Colonel’s Bequest |

|

|||

|

Studio: |

Sierra

On-Line |

|||

|

Designer(s): |

Roberta

Williams |

|||

|

Part of series: |

Laura

Bow Mysteries |

|||

|

Release: |

October 1989 |

|||

|

Main credits: |

Programming: Chris Hoyt, Chris Iden |

|||

|

Useful links: |

Playthrough:

Complete Playlist Parts

1-7 (422 mins.) |

|||

|

The Colonel’s Bequest holds a certain amount of nostalgic

value for me — the way I remember it, I think it must have been my very first

«unboxing» experience, way back in an era when second- and third-hand pirate

copies of videogames, transmitted through friends and colleagues, were still

the norm in faraway Soviet Russia. Back then, it all looked like a miracle —

an actual box! Colorful art on the

front and back! Serial numbers! Manual! A cleverly designed copy protection

system that comes with its own magnifying glass! And, of course, all those

carefully numbered and marked floppies — I think I still only had a 5-inch

drive at the time, so these funny little square 3.5-inch diskettes had to

just lie around for a while. Even if the game were to suck in all sorts of

terrible ways, I knew I had no goddamn right to dislike it. (Honestly, looking

at digital copies of all that memorabilia even today, I think that the

packaging was quite outstanding for its time, and can still serve as a good

example of how to serve your product to the customer). Fortunately,

the substance turned out to be quite on par with the packaging. Combining a

decent – and even somewhat disturbing – mystery plot with the atmosphere of

both a Gothic novel and the exuberance of the Roaring Twenties, The Colonel’s Bequest once again

expanded the borders and technical potential of the Sierraverse in ways that

few people thought possible in 1989; and although most of the veteran players

today prefer to gush about its sequel, The

Dagger Of Amon Ra, the original Laura Bow mystery as envisaged by Roberta

Williams continues to retain that exclusive bit of «silent-movie charm» that

is naturally lacking from the sequel. As

was already established with her King’s

Quest games, Roberta Williams was never as much a talented «video game

storyteller» as she was an awe-inspiring «video game mother figure». Her

games never featured much creative dialog (because she was never an

outstanding writer) or challenging, unpredictable plot twists (because she

was a traditionalist at the core, and seems to have always operated on a «far

wiser people than us have already invented all the good stories» basis). But

she had a great knack for transferring humanity’s accumulated artistic

baggage into the medium of video games, providing classic fairy tales with a

new kind of digital life, showing great love and admiration for the genre and

— this is going to be particularly important to us — never shying away from

their gruesome and gory elements. Thousands of mentally traumatized gamers

probably still remember all the jump scares they got from Evil Wizard Manannan

or that pesky cave troll in King’s

Quest IV... Gruesomeness

and gore was actually the way things started out with Sierra and Roberta

Williams way back in 1980, when they were releasing their very first

graphical adventure game — Mystery

House. Incidentally, thrillers and mysteries were the real love of

Roberta Williams, and even after Sierra struck gold with King’s Quest, leaving Roberta with the necessity to continue

upgrading that fairy-tale formula, her craving for detective stories never

subsided. Finally, after King’s Quest

IV gave the lady her biggest hit yet, she decided that the time had

finally come to diversify her line of production, and that implied going back

to the spirit of Mystery House and

fully upgrading it for the next generation of video gaming. The Colonel’s Bequest does indeed

share the premise of that game — the protagonist being locked up in a large

mansion with bodies piling up all around, an idea itself borrowed from the

concept of Agatha Christie’s Ten Little

Indians — but puts it in a much larger, multi-level context, where the

surrounding atmosphere matters just as much — actually, matters much more than — the mystery itself. As

far as I can tell, The Colonel’s

Bequest — as opposed to its sequel — is Roberta’s own brainchild in its

entirety, though, of course, she is not directly responsible for the game’s

beautiful visual art or excellent soundtrack. She would only assume such full

responsibility one more time (for King’s

Quest V), with all of her other games made either in collaboration with

other Sierra talents (Jane Jensen, Andy Hoyos, etc.) or being «Roberta

Williams» largely in name only (most of The

Dagger Of Amon Ra would actually be written by Josh Mandel). This makes The Colonel’s Bequest share all the

common flaws of a typical Roberta Williams game — such as the near-total lack

of humor (except for all the unintentional bits), a certain rigid

straightforwardness, relative absence of subtext, etc.; but all these

qualities were, amusingly, just as helpful in the early days of computer

gaming as they may seem detrimental today, because the «minimalism of

essence» as espoused by Roberta fits in very well with the «minimalism of

style» as determined by the improving, but still quite sparse technical

possibilities of the late Eighties / early Nineties. What

I’m trying to say is that Roberta Williams was really the perfect gamemaker

for the years of 1988-89, and these were

the years during which she delivered her two best games: King’s Quest IV and The

Colonel’s Bequest. And even though the fame and appeal of the latter

seems to have largely faded away with time — even when people nostalgically

mention Laura Bow, they usually do it with Josh Mandel’s The Dagger Of Amon Ra in mind — I think that this is more the

result of an unfortunate combination of circumstances than of the game’s

actual flaws. After all, unlike King’s

Quest IV, The Colonel’s Bequest

did not trigger a revolution in the gaming world (even if it did introduce

some unprecedentedly neat new features); for many players, it was just

another murder mystery game, of which there were already quite plenty on the

market. Well... maybe it was, yes. But it was definitely a murder mastery

game done in great style, and hopefully what I plan to write below will

remind us all that every once in a while, great style may happen to be even

more important than great substance. |

||||

|

Content evaluation |

||||

|

Plotline

That

said, at least the set-up is pretty decent for an old school adventure game.

The story takes place in the 1920s, with you playing as Laura Bow, a young

and, as befits the «Roaring» decade, independent-minded student at Tulane

University in New Orleans, who is invited by her friend, the dapper-flapper

Lillian Prune, to spend the weekend at her uncle’s old plantation house

somewhere down in the bayou — apparently, Colonel Henri Dijon, a grumbly old

veteran of the Spanish-American War, has called a large family gathering for

some unknown purpose, and Lillian is loth to take the long river journey on

her own. After arriving and acquainting themselves with the large crowd of

people — which includes not just the Colonel’s close relatives, but his

personal doctors, lawyers, and staff as well — Lillian and Laura soon learn

the real reason for the invitation: apparently, the Colonel has just written

up his will, in which he wishes to distribute all of his impressive wealth in

equal shares among everybody present (except for Laura, of course). This

immediately sets off a storm of bickering — apparently, none of the guests

are able to stay civil for long — and soon after dinner, as the guests retire

for the evening, somebody promptly begins bumping them off, one by one... This

is, of course, not so much a set-up for a proper story as it is for a board

game like Clue, and, try as I

might, it is hard to find anything even remotely special about the plot. The

stylistic combination of the «old world», represented by the slightly

dilapidated plantation mansion itself, the elderly characters such as the

Colonel and his sisters, the ancient ghosts in the cemetery, the antique

newspapers in the attic etc., and the «new world» of the 1920s, represented

by the younger guests and their habits and attitudes, works well enough, but

it’s more a matter of atmosphere than storyline, and will be discussed later.

The plot, however, mostly just gets busy trying to suck in every single

stockpile character feature from the classic pulp market. Characters include

the Creepy Lecherous Old Doctor; the Ruthless Cynical Lawyer; the Silent

British Butler; the Slutty French Maid; the Wise and Loyal Black Cook; the

Dumb And Beautiful Blonde Hollywood Actress; the Dashing, Egotistically Evil

Young Gambler With Moustache; the Drunken Old Widow Sister... have I

forgotten anybody? Oh yes, there’s also a parrot (who, naturally, talks and

can occasionally spill some useful beans), an old warhorse and an old dog —

all of whom can be suspects, too, from a certain angle, if you so desire. The

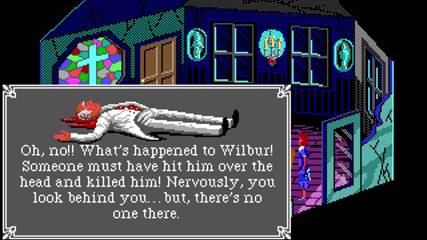

story, formally segmented into eight hour-long «Acts» that stretch out from

early evening into late night (you have to complete a certain set of four

«quarter-hour long» actions to trigger the next act) develops in a fairly

straightforward manner: Laura wanders around the mansion and the outside

grounds, interacting with the various guests for questioning and eavesdropping

on some of them for extra bits of their personal stories. At the beginning of

each new «Act», she can (and usually will, unless you really suck at

pathfinding) run into a fresh dead body of one of the guests — which will,

however, miraculously disappear as soon as she leaves the grounds, leaving

her unable to prove to anybody else out there that a new murder has just been

committed. This is just a crude artificial device, of course, planted by

Roberta to keep the game moving in accordance with the same pattern for all

the acts — otherwise, it’d require too much extra work on the characters’

reactions to the murders — unfortunately, it makes it rather hard to suspend

the proverbial disbelief, reminding you over and over again that this is just

a digital equivalent of a board game, rather than a true life simulation. Another

piece of bad news is that, for all of her alleged independence and

astuteness, Laura Bow is not much of a character herself — not in this game, at least. Regardless of how

many private conversations you have overheard, of how much evidence you have

gathered, of how many bodies you have located, you are essentially unable to

fit yourself into any of this story — other than getting killed, that is, if

you do something that you weren’t supposed to be doing (like... taking a

shower!). You cannot prevent any of the murders; you cannot properly warn any

of the guests; you cannot call the police or make anybody leave the

plantation island before dawn. All you can do is hop around, talk, pick up

objects that don’t make sense to anybody other than yourself (even if it’s a

blooded poker or an actual weapon), and wait for the next turn of events.

There is only one serious choice of action made available to you at the very

end — and you’d have to be very

dumb, or, actually, more like «maliciously curious», to take the Bad Ending

choice out there. All in all, when it comes to Roberta Williams’ famous list

of Intrepid Female Protagonists, Laura Bow loses to Princess Rosella hands

down. (Although it would take Adrienne Delaney from Phantasmagoria to fully complete the «Helpless Damsel Watches As

World Burns» trope). The

game’s dialogue somewhat inverts Woody Allen’s classic «the food is so

terrible, and such small portions!» joke by being, in fact, quite terrible,

but coming in VERY large portions for compensation. If you aim for a truly

thorough exploration of the game, you shall soon find yourself doing almost

nothing but talking to the various characters — particularly in the first two

or three acts, when most of them are still alive. You can ask or tell just about anybody about just

about anybody else, or anything

else, including the Colonel’s pets and each single item in the

ever-increasing inventory of your evidence — moreover, in an absolutely head-spinning

twist you can expect to get different

answers in each new act, which,

altogether, makes up for hundreds, if not thousands of lines of dialogue: the

hugest ever amount of text in a Sierra game up to that moment. The down side

is that approximately 90% of that dialogue is either completely useless, or

totally boring, or both (the most common case). E.g.: «Ask the Colonel about

the monocle» — ‘so it’s a monocle, what

do I care?’ (Act I), ‘leave me

alone with your monocle!’ (Act II), ‘I

don’t know anything about a monocle!’ (Act III), ‘stop pestering me about monocles, young lady!’ (Act IV), ‘monocles? we don’t need no stinking

monocles!’ (Act V). (I actually made all these up on the spot, but I

think I got the spirit largely right). Getting a useful clue from all this

talk is a needle-in-a-haystack kind of thing. And don’t even begin to hope

for anything humorous to come out of it — as we all know, Roberta Williams

simply does not have a sense of humor, period. I don’t think any single

character drops even a single joke throughout the entire game; it would take

Josh Mandel and The Dagger Of Amon Ra

to teach them Roaring Twenties’ people to actually talk funny. Although

pretty much each character has their own backstory and their own skeleton in

the closet (including the Plantation itself, which has its own mysteries

dating all the way back to the Civil War), they are all board game

clichés. Some have problems with alcohol, some with gambling, some

have secret or semi-secret romances or painful breakups going on, some are

victims of circumstances and some are schemers and predators... it’s all in

the line of duty. Everyone is just a cardboard figure, voicing predictable

issues and behaving in predictable patterns. The dirty doctor makes vain

passes at you, the nasty lawyer keeps on insulting you, the flirty French

maid gets it on with whoever she lays her eye upon, the silent English butler

keeps silent, and only the Loyal Black Cook feels lonely enough to regale you

with a few lengthy stories about the Plantation and its former and present

owners after you gain her trust (if

you get her trust — this is something you must work for), but even the Loyal

Black Cook, as expected, is a church-going Voodoo practitioner with a sixth

sense about things. Pretty

much the only character with a curious case of split personality is Laura’s

best friend Lillian, who starts out as a snarky, life-savvy flapper, but soon

emerges as an actually deeply psychologically disturbed victim of a childhood

trauma, with bipolar disorder just around the corner. Of course, she is not

given much space to evolve and thrill you as a character, but at least she is

somewhat memorable, unlike any other character in the game; I do remember the

original strange feeling I got upon watching her transform from a character

who felt fun to be around to a character who felt dangerous to be around, and

I guess this motive is something that holds a special meaning for Roberta as

well, as she would later continue to explore it with Phantasmagoria. All

in all, though, remember that if you do decide to boot up The Colonel’s Bequest, you’re not

really doing it for the story — if you want top-level murder mysteries and

detective romps in your adventure gaming, you’re much better off with the Nancy Drew or Tex Murphy series. The genius of Sierra On-Line in its Golden Age

rarely lay in the story plotting or dialog writing anyway, and the games that

were personally designed by Roberta Williams are probably the best evidence

of that. All that The Colonel’s Bequest

had going for itself in that respect back in 1989 was the hugeness and

monumentality — such a great lot of content compared to pretty much anything

that came before — and with time going on, this is obviously no longer a

relevant factor, what with so many games now having so much more action and

dialogue, and all of it a far higher quality. Let us take a look, then, at

some other aspects of the game to see what, if anything, actually continues

to make it worth the while of the Discerning Antiquarian. |

||||

|

Puzzles

We

should certainly admire Mrs. Williams for her noble effort to do something different, compared to Sierra’s

previous games. For one thing, The

Colonel’s Bequest completely dispenses with the classic point system — in

this game, you do not play for points, you play for information and evidence.

Unfortunately, nothing too good came out of the idea, because the essence

remained the same: the game still requires you to successfully complete a

large number of actions in order to achieve the best detective ranking at the

end — most of these actions are optional, and many can be easily missed, and

the only difference is that now the game does not explicitly let you know

when you have performed a useful task. (There’s a tiny encouraging beep

played whenever you pick up a piece of evidence, but you have to keep your

sound on all the time, and there are no such sounds when you do something

useful in a different way — for instance, ask one of the characters an

important question, or investigate a stationary, non-removable object). For

another thing, this is probably the first Sierra game which can be beat —

technically — by doing almost nothing.

A veteran speed-runner could technically complete the game in about 5-10

minutes; all you have to do is run around the mansion and the outside

grounds, stumble into certain NPCs or groups of NPCs, and trigger the

clock-advancing events, about 30 of them in total to cover the entire eight

«acts». You don’t need to discover

any bodies or secret locations, you can get away without picking a single

piece of evidence (other than take one key off one body at the very end), you

might not want to talk to any of the guests at all (and I wouldn’t blame you,

as most of them really have very little to say). And you can still nail the killer at the end, even

without knowing who exactly he has killed. The

only thing that will be different during the final reckoning is your status

on a little thermometer that can, theoretically, go all the way up from

«Barely Conscious» to «Super Sleuth». Both the lowest and the highest rankings are comparably difficult to achieve — to

be «Barely Conscious», you really have to go out of your way to not see anything out of the ordinary during

the night (like, actively avoid all the locations with dead bodies, which is

itself a logistic challenge), whereas the «Super Sleuth» ranking can be

achieved only if you successfully complete more than 95% or so of all the

tasks marked in your notebook, some of them related not just to the main

topic, but to various outside matters as well (e.g. «Person Wishing To End An

Affair», «People With Gambling Habits», etc.). As the game rarely gives you

any hints in the process, this is excruciatingly difficult to achieve without

a walkthrough or hint book, but that’s Sierra On-Line for you, nothing too

surprising here, other than the lack of intermediate satisfaction because of

the elimination of the point system. In

other words, beating the game in general is super-easy; beating it with the

highest possible rank is super-difficult, though there are maybe only two or

three challenges in all which I would consider completely unfair (for

instance, a couple of things that depend upon randomized scripts running

during your visits to secret rooms). Even so, The Colonel’s Bequest is not so much a «puzzle-solving» game as a

«disciplinary» game: you get most of your progress not from wrecking your

brain for complex solutions to specific problems, but simply from being as

meticulous and obsessive as possible. Discipline yourself to look at everything (not forgetting the

magnifying glass!), push, pull, open,

and tamper in various ways with everything that can be tampered with, talk to everybody, and you’re pretty

much set. There is, I think, only one multi-step puzzle that you have to

solve in order to discover the plantation’s ultimate historical secret, and

even that one hardly requires true creativity, just a lot of snooping around

to collect all the necessary paraphernalia. One

more innovative detail in the game was the addition of a bunch of post-game

hints, issued to you on account of everything you forgot or did not figure

out while playing. These are often quite vague and faint (e.g. "look for multiple rusty objects",

"murderers leave ‘tracks’, check

them closely!", etc.), but it’s still better than nothing — prior to

The Colonel’s Bequest, the only way

to get any hints from Sierra was to

give the company more money (by calling their service or buying a hint book).

The same technique was also borrowed by Al Lowe for the third game in the Larry series, on which he was working

at the same time, but I think that ultimately it did not stick, largely

because the only reason for a post-game hint series is to point out the

optional tasks that you might have missed, and as time went by, the number of

optional tasks with extra points in Sierra games grew progressively smaller

anyway. For this particular game,

however, where almost any task is

optional, the hints were quite essential, as they could at least point you in

some vaguely specific directions. In

any case, the puzzle system of The

Colonel’s Bequest is a classic case of Noble Intentions soiled and

neutered with Dumbass Execution. The single worst thing is the total

detachment of the game’s finale from the protagonist’s work over the eight

«Acts» — none of your choices and actions have any direct bearing on the

denouement, and any evidence that you may have collected is useless to the

plot (it only makes an impact on your final ranking). Ultimately, this makes

the game fail as a true «murder mystery challenge», in much the same way in

which it just failed as a potentially involving «story». Is there anything, then, that in any way

redeems it as a memorable playing experience?.. |

||||

|

Atmosphere As usual in Sierra games, when all else fails, atmosphere and

ambience come to the rescue. I would all but bet my life that nobody who’d

played The Colonel’s Bequest back

in its time remembers it specifically for its brilliant plot or inventively

designed puzzles — but that most people probably remember how their Laura Bow

ended up in the hungry jaws of a swamp alligator, or fell under the knife of

the murderer while trying to take a shower, in a totally and utterly

gratuitous and just as totally unforgettable stylistic nod to Psycho... «just because we can».

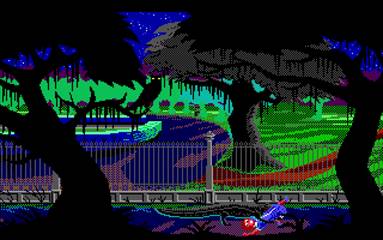

Or, maybe, not so tranquil after all, because the

second and even more pervasive part of the atmosphere is the Legend of the

South. Where games like Resident Evil

like to trap you inside creepy, danger-choked closed buildings, making you

yearn for the wide open spaces, The

Colonel’s Bequest does the opposite — it’s a game that promotes agora-

rather than claustrophobia, if you get my meaning. In theory, staying outside

the plantation house is not really as dangerous as staying inside it — the

murderer does not seem to be interested in getting to you in the open air,

and all you really have to do is avoid getting too close to the

alligator-infested swamp and river. But in practice, staying outside at

night, with all the eerie shadows thrown around from the Spanish moss on the

trees, with all the croaks and creeks of unseen living beings, with glowing

alligator eyes staring at you from nowhere, with thunder and lightning on the

horizon... wandering around this place is really like a cold shower right

after the warmth and coziness of the sunny spaces at Tulane. The inside of the plantation house, especially in

the first few acts while most of the people around you are still alive, is

where you really want to find yourself as quickly and as much as possible. I

remember this contrast vividly — one minute, you’re standing in the outside

darkness, with the wind howling and the frogs croaking and maybe a couple

hungry alligators snappin’ at your heels (it was all imagination, of course,

but the game did great at instilling fear inside your heart); the next

minute, you step inside the living room and there’s the dashing Gloria

Swansong (yes, with a hilariously brilliant final -g) sitting in her feathers and boas, listening to life-giving,

relaxing bits of ‘Maple Leaf Rag’ or ‘The Entertainer’ on the Victrola. No

other game at the time succeeded so well in making you run into the welcoming

hands of modern civilization from the vicious, terrifying maw of Mother

Nature. Of course, modern civilization had its own drawback:

a serial killer on the loose, who could crop up in the least expected places

— from the bathroom to an empty closet in the hall. The plantation house had

other ways to kill you as well — Laura could end her life buried under a

fallen chandelier, chopped in two by a rusty axe on an old suit of armor, or,

ironically, squashed to pulp under the weight of civilization’s latest

achievement, the electrically-powered elevator. Still, for some reason, the

plantation house was never nearly as creepy as the outside, and it was fun

exploring how modern life, in one way or another, was finding its way inside

something so decidedly mid-19th century. There are tons of fun artifacts,

from mechanical pianos playing rolls to Murphy beds to old-fashioned doll

houses to weapon collections; almost each room in the house has its own

special face, even if, unfortunately, there is only a very limited amount of

things you can do with them. (You can

close and open the Murphy bed, if you so wish, provided there isn’t a dead

body lying on it!). It is all these contrasts between the old and the

new, the safe and the dangerous, the creepy and the comfortable, that really

make the game worth playing and its universe worth visiting. The experience

is not particularly «realistic»: even in those of her games which are

supposed to take place in the «real» world, Roberta Williams is still far too

fascinated by Gothic novels and Hammer horror to make her environments and

her characters’ actions fully believable (this would reach a certain absurd

peak with Phantasmagoria half a

decade later), but does this really matter when you’re going for more of an emotional

punch than an intellectual appraisal? Particularly when that emotional punch

is more likely to be received by simply wandering from one game screen to

another, rather than by actually doing

something?.. |

||||

|

Technical features |

||||

|

Graphics

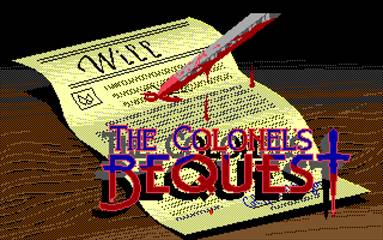

Already

the introduction was done in great style: a close-up of the Colonel’s will,

with his hand slowly tracing out the signature (Col. Henri A. Dijon), whereupon a bloody dagger pins it to the

table, and the dripping blood gradually transforms the game’s title from blue

to red. This kind of detailed cinematography was never before seen in a

Sierra game, and immediately created the feel that you’re about to witness,

and participate in, something truly special. Thereupon, the scene would

change to an introduction of all the NPCs ("Starring...") — who were seen both in their miniaturized

sprite forms and in animated

close-ups: an excellent device that immediately drew you in closer to the

«actors»; remember that up until then, Sierra was really skimpy on close-up graphic design for both the playable

and the non-playable characters. The

backgrounds were painted with two things in mind: detail and atmosphere. The

importance of the second parameter also becomes clear as early as the intro,

when the opening scene of Laura and Lillian meeting on the lovely greens of

the sunlit campus of Tulane University is immediately followed by the mix of

black, dark blue and deep green of the plantation island at night — giving

you just a quick opening glimpse of safety and comfort before landing you

fair and square into the gloom and danger of «non-civilized» America. The mix

of vague shapes and dark shadows as you move from one plantation screen to

another is often disconcerting and confusing, and it always looks as if one

of these shadows might materialize and grab you... and occasionally it does,

if the shadow in question is a hungry alligator. Detail, on the other hand, serves a more

pragmatic purpose, since you are expected to be hunting for evidence, and

evidence may be concealed just about anywhere. Unfortunately, about 90% of

the surrounding paraphernalia are just red herrings, but then again, isn’t

that just like it is in real life? Almost every single room in the mansion is

cluttered with stuff, and it’s usually lovingly depicted stuff: bookshelves

with colorful titles, mantlepieces with shiny exhibits of guns, richly

upholstered chairs, globes, vases, pots, toys, you name it — apparently, the

plantation’s previous owners were quite compulsive hoarders in their day.

Most of that stuff is depicted quite well, too, even such tiny bits as a

small derringer pistol in a glass case — I do not recall ever wasting time,

wrecking my brain on how to identify an object before trying to

"look" at it or pick it up. Most

importantly, The Colonel’s Bequest

featured far more animation than ever before in a Sierra game (the real

reason why the whole damn thing ran so slow). As you walk around the

plantation, froggies are jumping around, alligators move from land to water

and back again, and huge lightning flashes in the sky keep spooking you into

thinking they’re coming for you sooner or later. Inside the mansion, clocks

are ticking, lights are flickering, the parrot is getting impatient in its

cage, and the guests are busy talking, smoking, drinking, eating, reading, or

snoring in their beds; nobody ever

just stands still at their post. As a result, the world of The Colonel’s Bequest was far more

dynamic than, say, the world of Police

Quest II, even if the latter took place on a lonely island in the swamps

and the former in the supposedly hustlin’-and-bustlin’ Lytton City. The

best work of all, arguably, was done for the close-up portraits of the

characters and their animations. The actual sprites look about as ridiculous

today as they always did — there’s no escaping the sad graphic limitations —

but in close-up (and you are going to see a lot of close-ups if you’re good at sleuthing and discover all the

ways to spy on the different characters early on in the game), they are all

fully representative of their personalities: the gruff and grumpy Colonel,

the salacious and unpleasant Doctor, the arrogant Lawyer, the dashing

Hollywood actress, the sexy French maid, etc. There’s even some reflection of

character development in the close-ups — for instance, Lillian looks all

sweet and happy while chatting up people at first, then has her expression

change to all-out rage and anger in Act V during her sorting things out with

«Uncle Henri», when she learns that she is apparently not nearly as «special»

to him as she’d always thought. Of

course, all of these praises have to be taken with a grain of salt, as we’re

still talking graphic standards of 1989. But if I have any real complaints

about the game, they are certainly not going to be directed at the visuals —

which seem to have been produced with far more love and care than the actual

plot or dialog. The Colonel’s Bequest,

like almost any Roberta Williams game, is a triumph of atmosphere and style

over substance, and the game’s artists, Doug Herring and Gerald Moore, seem

to have invested much more personality into its characters than Roberta

herself. |

||||

|

Sound

Sound-wise, pretty much the entire game is built around the

alternation of «merry» and «sinister». The opening theme is a haunted-house

church organ dirge, after which the credits roll accompanied with a catchy,

danceable piece of woodwind-led MIDI vaudeville. Laura Bow at Tulane University

gets her invitation from Lillian to the sound of a lively foxtrot (or is that

the Charleston? I confess I’m really bad at my popular 1920s dances) — but

arrives at the Plantation Island immediately after to the sound of a grim

cemetery tune, symbolizing not so much the upcoming murders as the overall

air of death, desolation, and otherworldliness associated with her

destination. All of these mood shifts are quite vivid; the themes truly set

the mood rather than merely hint at it from a formal point of view. Unfortunately, there is not really a lot of music beyond the

introduction and ending sections; music that would constantly run in the

background, like it did in Leisure Suit

Larry III, for instance, would probably detract from the suspense — thus,

while wandering outside the Mansion, Laura’s journeys are only accompanied

with sound effects (whistling winds, thunder in the sky, croaking frogs,

hooting owls, splashing alligators, that sort of thing), which is still

creepy enough, I guess. Inside the house, most of the music actually comes

from music-playing sources — in the Billiard Room, for instance, Gloria

Swansong will ceaselessly spin her Victrola tunes, which are either borrowed

by Ken from 1920s’ dances or composed by him in the appropriate styles;

Laura, meanwhile, can wind up the mechanical piano and play a bunch of nice,

brief arrangements of Scott Joplin ragtime pieces (‘Maple Leaf Rag’ goes off

real great!). In addition, the French maid Fifi seems to have really cool

musical taste, with a nice stock of classical records such as Satie’s

‘Gymnopédie No. 1’ and Ravel’s ‘Bolero’, adding a whole extra

dimension to her stereotypical sex doll personality. Every

now and then, there is also a musical joke or outside reference included —

for instance, the shower murder scene almost obligatorily alludes to the

strings of Psycho (just like the

shark theme in King’s Quest IV had to be borrowed from Jaws), and the ‘Drunk Ethel’ theme

playfully and painfully distorts, contorts, and mutilates the melody of one of

the game’s other themes... for no other reason than to slightly brighten up

your night when you’ve just narrowly missed being eaten alive by an

alligator, and need to be reminded of the fun side of life which involves

drunken old ladies fearlessly roaming on the premises (no alligator would

probably touch one of those). In

short, despite the laconic nature of the soundtrack (everything put together,

including the rags and Satie, occupies about 40 minutes at maximum), it is

extremely vital to the game — and it actually sounds not half-bad even with

an old PC Speaker (which is the way I first heard it, having no sound cards

or Roland synthesizers)! I also think this was the first time in Sierra

history when the soundtrack included so many different MIDI rearrangements of

classic musical pieces, in addition to original composing — it sure helped

that most of them were already in the public domain by 1989. |

||||

|

Although, in general, the gameplay system in The Colonel’s Bequest was typical of

most of Sierra’s second-generation golden-age titles, the stylistic and

substantial changes introduced by Roberta all but required things to be at

least slightly different in terms

of the accompanying interface as well. In fact, things are quite noticeably

not what they used to be right at the start of the game — featuring what is

probably the single most original «copyright check» device in Sierra’s

history, so elegant, in fact, that it is the only copyright protection

mechanism I find myself occasionally enjoying.

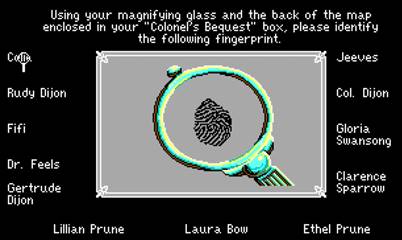

Even before the title screen, you are asked to identify a fingerprint

belonging to one of the game’s characters (each guest has two different ones)

which you have to look up in the accompanying copy protection sheet that came

with the box — except that sheets like that could be xeroxed, so they are

cleverly masked on the sheet so that you can only really see them with the

aid of a special red-lens magnifying glass. (Naturally, since there were only

12 characters, you could theoretically take your time and reach the correct

answer through a lengthy series of trials — with the initial chance of

success being 1 in 24, that would not be such a tough job — but then again, I

doubt people could be that patient even back in 1989). This is original, elegant, classy, and, in a way, constitutes

the most actual detective work you shall be doing throughout the game — and

not much of a determent, since sooner or later you shall begin to memorize

those nifty little prints anyway. It also prepares you to realize that this is

going to be a somewhat different

experience, and, indeed, quirky little changes from the usual style of King’s Quest or Space Quest quickly follow. For one thing, since the points

system has been eliminated, the overhead menu bar is typically hidden; it can

be easily accessed by pressing a key, but generally, the bar never obstructs

your sight, contributing to the «cinematic» experience. For another, the

usual style of «black text inside a simple white box» has been replaced here

with «white text inside an ornamental black box», giving the game both a bit

of Art Deco flavor and a murder

mystery one. (Unfortunately, they couldn’t do this with the pulled-up menu

itself). The game’s parser shares the usual flaws and benefits of a

Sierra parser, recognizing quite a few commands and objects but certainly not

enough to be fully adequate to the amount of detail in the pictures. The good

news is that there are shortcuts: interaction with other NPCs is made easier

by allowing you to press key combinations to «Ask about...», «Tell about...»,

«Show...», and «Give...» (you only need to type in the object of your inquiry

or transaction; the addressee will be automatically determined by the game

based on your relative positioning on the screen). «Look at...» is also a

shortcut, but, unfortunately, there is no specific «look at... with the

magnifying glass» shortcut, which really drags after you actually get the magnifying glass and have to

type that in repeatedly (yes, sometimes it is actually necessary). True to its detective story mission, the game has no action or

arcade sequences whatsoever, the most «action» thing about it being the need

to watch your step, particularly on the outskirts of the plantation where

deadly bogs and hungry alligators await, and an occasional timed sequence or

two, where you have to take a quick decision in order to influence the story

or get a higher ranking. This can certainly lead to a point where you simply

get tired of spending most of your time «asking» or «telling» other people —

but at least with people dropping dead around you at a steady pace, by the

time the last acts roll around, there is hardly anybody left to ask (and the

few people around you who are still

alive typically get grumblier all the time and eventually just refuse to answer

any more questions — what a relief!). As I already mentioned above, the one bad thing about

eliminating the points system is that you are never properly informed of your

overall progress, except for the major events that advance time 15 minutes

forward. Sometimes it is fairly obvious that you have progressed, for

instance, when you pick up an object or notice something unusual about it

through close scrutiny; at other times, it is much less so, e.g. when you

finally accidentally ask somebody an important question or spy upon a meaningful

conversation (some conversations are there only for decorum, and some

actually reveal significant information, and it is not always evident which

is which). I can understand Roberta’s disdain for the classic points system —

when people play for points, they tend to turn the entire experience into a

mechanical hunt-for-achievement algorithm — but couldn’t she have at least

introduced, I dunno, a flashing lightbulb or something each time you make

another tiny step on your long and winding road to «Super Sleuth»? And those

«hints» at the end really do not help all that much. Still,

with everything pooled together, Roberta does achieve her goal which she

proudly states in the «About...» section of the menu: "The Colonel’s Bequest" is different

than the so-called "normal" adventure game as it was designed

around a story and characters rather than a series of puzzles..."

Like these changes or not, the game was an interesting experiment in

broadening and tweaking Sierra’s standard formula, and while not every such

experiment did work in Sierra’s history (here’s looking at you again, Codename Iceman!), the tweaks

introduced to The Colonel’s Bequest

mostly worked. At the very least, the new interface certainly contributes to

the overall atmosphere — and, as I said, this game is all about atmosphere. |

||||

|

As is so usual with Sierra, anybody who begins and ends their

judgement of The Colonel’s Bequest by asking the question «just how

good is this game as a game?», will almost inevitably descend into a

plethora of complaints (many of which, though probably far from all, have

been tackled above) and even more inevitably start bringing up LucasArts or,

in this case, some classic Tex Murphy game or The Last Express

to back up the case of what a true murder mystery videogame may and should

look like. As a game, The Colonel’s Bequest was not

particularly good when it came out and it certainly has not improved with

age. But as a multi-media experience in which the total sum is

expected to be greater than the parts, The Colonel’s Bequest was an

inventive, inspired, and technologically creative application of the classic

Sierra formula. In fact, its principal flaw was not so much the lack of

serious puzzles or the stupid plot or the boring dialog, but rather the

emphasis its advertising campaign took on how it was all about you, the

player, being supposed to practice your logic skills in a game of wit — when,

in reality, the most wit one has to exercize here is on figuring out what to

do with that strange red magnifying glass in your box. Now if only the game had advertised itself for what it really was — a

trip to a slightly surrealistically-warped dimension in which you, the

player, made characters from the 1920s bump into and clash with memories from

the 1860s, with just a touch of Edgar Allan Poe from a more distant past and

Alfred Hitchcock from a more distant future sprayed around the edges — its overall

reputation might have securely solidified by now. The underlying cultural and

moral implications to this «clash» are simple enough — the present held in

the iron grip of the past; the greed, stupidity, and vanity of the modern age

next to the eternity of nature and the briefness of human life in comparison;

the «honored tombstones» silently looking down on their dishonorable

descendants, etc. — but the atmosphere of the game really makes them work.

And although it is true that in most respects, The Dagger Of Amon Ra

would put The Colonel’s Bequest on its knees (once the franchise

essentially migrated from Roberta’s lap under the wing of Josh Mandel), the

second game in the series could never even begin to be described with the

term ‘haunting’ — which I seriously considered employing at the

beginning of this review. But then I thought it a little too tasteless. (So I

found this way to stick it at the end instead!) Of course, given the sheer number of positive retrospective reviews

and the typically warm welcome that Colonel’s Bequest-related videos

seem to receive on YouTube nowadays, it can be stated with relative safety

that the game is not completely going away any time soon — and that its art

style, soundtrack, atmosphere, and (not the least) educational value are

still capable of attracting attention and providing inspiration, maybe even

from some people born in the 21st century. There are even some indie-style tribute

projects floating around (e.g. Julia Minamata’s ongoing Crimson Diamond

project), and there have been attempts to revive the game by remaking it in 3D

(abandoned, I believe) — which would be a mistake, I think, since I honestly

do not believe that The Colonel’s Bequest would ever work that well in

a modernized version; to do that, you’d have to vivisect its childlike soul,

and that would make it into something completely different, for better or

worse. Instead, let’s just make sure it continues to be available and to haunt

us people of the 2020s with its 1980s vision of a 1920s future ruined by the

ghosts of the 1860s... |

||||