|

The Dagger Of Amon Ra |

|

|||

|

Studio: |

Sierra

On-Line |

|||

|

Designer(s): |

Bruce

J. Balfour / Roberta Williams |

|||

|

Part of series: |

Laura

Bow Mysteries |

|||

|

Release: |

1992; 1993 (CD version) |

|||

|

Main credits: |

Designers/Writers: Josh Mandel, Bruce J. Balfour, Andy Hoyos Programming: Brian K. Hughes |

|||

|

Useful links: |

Playthrough:

Complete

Playlist Parts 1-10 (620 mins.) |

|||

|

Up

until 1992, all of Sierra’s franchises had remained the exclusive

brainchildren of their respective parents. Roberta Williams worked on King’s Quest; Mark Crowe and Scott

Murphy continued to humiliate Space

Quest’s Roger Wilco in more ways than the galaxy ever thought possible;

Al Lowe kept digging into the bottomless pit of dirty jokes for Leisure Suit Larry. Yet as the company

continued to expand, making a bumpy, but ultimately successful transition

into the age of point-and-click, the basic principle of «one person, one big

idea» began to wane. With more and more people added to the staff, Sierra was

able to simultaneously work on numerous projects — way more than the original

veteran creators could handle — and this meant finally starting to detach

franchises from their «auteurs» and view them rather as the collective

property of the company. As was common in the Sierra family, any such new

development had to be centered on the Holy Mother — Roberta Williams — and it

was her who willingly sacrificed her youngest daughter, Laura Bow, for the

greater good of the firm. Although credited as «creative consultant» for The Dagger Of Amon Ra — the second and

last game in the Laura Bow Mystery

series — this was probably just a polite way of reminding us who had invented

the character in the first place. I honestly have no idea what sort of

«creative consultations» the game’s designers would be running to get from

their boss — 1920s hat fashions? (I don’t think Roberta was ever into that angle). Anyway,

the two most important names in the creation of The Dagger Of Amon Ra were Bruce Balfour, a mystery and sci-fi

writer and game designer with a bunch of poorly known strategy and adventure

titles behind his belt; and Josh Mandel, who had already been with Sierra for

a couple years, working various odd jobs from producing to voice acting to a

little writing. Balfour was in overall charge of the project and supplied

much of its «mystery» angle; however, most of the actual writing for the game

came from Mandel, who was ultimately responsible for the main spirit of The Dagger — besides, Balfour did not

last long at Sierra, whereas Mandel, having cut some serious new teeth on the

game, would go on to become one of the most important people at Sierra for

the rest of its duration. Thus, The

Dagger Of Amon Ra remains largely associated with Mandel, the guy to put

his nose inside almost every pie baked for almost every Sierra franchise in

the 1990s. Somewhat

predictably, since it would be difficult to find two game designers and

writers with more differing approaches to their work than Roberta Williams

and Josh Mandel, The Dagger Of Amon Ra

feels like it owes almost nothing to its direct predecessor, The Colonel’s Bequest, other than the

name of its protagonist — oh, and the fact that this is another murder

mystery where the protagonist finds herself in an enclosed, inescapable space

with murder victims dropping around her faster than the actual screen loading

times. The biggest technical difference is that the game was finally a talkie

(at least, in its final CD-ROM version from 1993; the original floppy disk

version from 1992 carried only text messages) — and thus, a perfect

playground for Josh Mandel to test out his own brand of witty humor. Where The Colonel’s Bequest excelled mainly

in terms of «sensual» atmosphere, The

Dagger Of Amon Ra would place a far stronger emphasis on the snarky,

sarcastic, post-modern intellectual side of things — something about as far

removed from Roberta Williams’ proverbially «housewife» approach to

game-making as possible. Admirably, Roberta herself endured and even

encouraged this, almost as if she were sending away her farm-bred girl to

Harvard University. It

is little wonder, though, that The

Dagger Of Amon Ra managed to assemble itself quite a cult following over

the years: even a cursory investigation of gaming forums, YouTube channels,

etc., shows that memories of it are still going strong, and that far more

people continue to have it on their minds than there are veteran fans of The Colonel’s Bequest. Of course, to a

large degree this is because the first game is older (in 1989, there were

still a whole lot fewer gamers around than in 1992-93) and has no voice

acting; but an equally significant reason is that Sierra’s Mandel-style games

typically appeal to the same kind of tongue-in-cheek,

sarcasm-over-sentimentality college geeks who, over the years, have succeeded

in making «LucasArts» sound so much cooler than «Sierra». Ironically, the

game still inherits a large number of flaws from its predecessor — to the

point of still being more of a «multimedia experience» than a proper «game» —

but the new-found slickness of its design and sharpness of its verbal humor

masks these flaws much more successfully. |

||||

|

Content evaluation |

||||

|

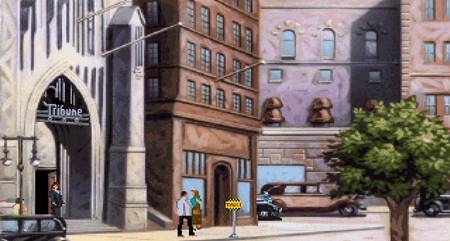

For Laura Bow’s second adventure, Balfour and Mandel decided to

bring the Southern lady a little closer to home; the Queens-born Josh Mandel

probably did not feel too comfortable about setting the action back up in

Louisiana, and thus it is that at the beginning of The Dagger Of Amon Ra, we see our heroine, having graduated from

Tulane, board a train for New York, where, in an age of new-found

emancipation for women, she is going to try and find herself a job with one

of the city’s prominent newspapers.

Largely because of a bit of a pull that her father has on the editor, she is

hired for a brief probation period, during which she has to cover and help

investigate the theft of a precious Egyptian dagger from the prestigious

Leyendecker Museum (loosely based on the Museum of Natural History). Like

its predecessor, The Dagger Of Amon Ra

is structured into several «Acts», within each of which you have to complete

a certain set of time-advancing actions in order to progress to the next

stage (and if you procrastinate or get stuck, some of these events are going

to take place even without you involved; the game constantly has the clock

running). However, this time around the world surrounding you is a bit more

of a sprawl — where The Colonel’s

Bequest immediately chained you to the Colonel’s mansion and plantation,

the entire first act of The Dagger Of

Amon Ra lets you freely roam around several locations in New York City,

using a cab to journey from one point to another, and it is not until the

second act of the game that you become fully confined to just one locked-in

environment (the Leyendecker). Admittedly,

the first act is not entirely disconnected from the rest of the game — you do

get to meet several important characters who shall be a constant presence in

the Museum as well, such as Detective Rian O’Riley, responsible for handling

the case of the missing dagger; «Ziggy», the ratty stool pigeon spending most

of his time around the local speakeasies; and the handsome stevedore Steve

Dorian (duh!) from the ship which had earlier transported the Egyptian

cultural artifacts to the US. Through those guys and other encounters, you

can gather some preliminary information on the case before the main course

starts at the Museum. However, in

general, I do believe, the chief purpose of the first act is to establish

the motif of «Southern Girl Makes Good In The Big Apple» — and recreate the

vibrant atmosphere of New York in the 1920s, ever so slightly warped with a

touch of sarcastic humor and the inescapable post-modern attitude. The

scene is a little messy at first, in that the game does not quite understand

if it wants to be a «loss of innocence» story (it certainly begins as one,

with Laura getting mugged as soon as she gets off the train to New York), a

straightforward detective story (which it reverts to as soon as you ask

anybody a pertinent question), or just a collection of humorous remarks on

the flaws and virtues of ordinary New Yorkers in the Jazz Age. Then again,

why should it necessarily be only one out of three? Granted, the «loss of innocence»

thing quickly dissipates, as Laura’s personality becomes one-sidedly

concentrated on the angle of «strong, stubborn girl making her way through a

world of male chauvinists»; and the flaws and virtues of ordinary New Yorkers

are left behind in the dust once we make the transition to Act II, after

which Laura almost never gets the chance to revisit those ordinary New

Yorkers again. (There’s a little bit of socially conscious banter centered

around Ernie Leach, the Museum’s African-American caretaker and a veteran of

World War I, but it’s short and most people will miss it anyway because it’s

quite a pain in the ass to catch Ernie in a talkative state). Sooner or

later, everything fades away, fizzles out, and makes way for the murder

mystery. Which

is not too good, because, frankly, the murder mystery sucks. At the very least, in terms of plot twists, intrigue, and

denouement it is in no way an improvement on the mystery of The Colonel’s Bequest. There are just

too many superfluous twists, too many plot holes, too many actions that do

not make any sense — and I do realize that this is not so much a serious

murder mystery as a parody on a murder mystery, but even parodies have to

have their inner logic, and this particular one places way too much emphasis

on «surprise» and «shock value» to have enough left for reason and logic. The

plot is certainly more complex than last time around — for instance, the

killer is ultimately revealed to have been motivated by more than one motive

in his endless rampage — but this is one case where extra complexity only

serves to ruin the mood. We

may at least be thankful to the writers for getting rid of the strangest plot

circumstance of the first game — namely, that throughout the game Laura Bow

is the only person to ever be aware that a series of murders is going on —

but it’s not as if they are doing a great job with it: this time, even when

some of the other NPCs do learn

that a murder has been committed, all they do is take notice, commend Laura

for a job well done, then continue to roam around the Museum as if being

locked up in a confined space with a serial killer running around is just one

of the many uncomfortable perks of life you’re supposed to walk your way

through. Yeah, sure, I’d love to get out of here and all, but... the front

door is locked, and the service guy has lost the key, so pardon me while I

just roam around all these corridors some more while the killer is taking

their time to decide whom to bump off next and in which particularly gruesome

way. Unsurprisingly,

while much of the dialog in the game — particularly in its first Act — is

sharp, witty, and hilarious, this only

concerns those lines which have the least of all to do with the mystery plot.

By contrast, a typical detective-related dialog runs something like this: The

Countess:

What are YOU doing here? Laura: I just happened to be hiding behind the tapestry. The

Countess: You’re LYING! Laura: How could you tell? The

Countess: Nobody just happens to

HIDE behind a museum tapestry! Laura: And nobody

just walks around a museum late at night with paintings under their arms. The

Countess:

Paintings? Oh, you mean THESE

paintings? Ah...I just found them laying around on the FLOOR...and I picked

them up so nobody would STEP on them! Laura: I don’t think so. The

Countess:

You don’t think so? Are you ACCUSING me

of something, you SILLY girl? Laura: What do you think? The

Countess:

I think you’re a RUDE girl who needs to

learn some MANNERS. The nerve... going around ACCUSING people of stealing

paintings! Laura: Did I say anything about you stealing them? The

Countess:

Well...of COURSE you did! Don’t try to

TRICK me, girl. I've got more tricks than you have BRAIN CELLS! I

only hope it wasn’t Josh Mandel who wrote this kind of tripe and forced the

poor voice actors to record it, but nothing could really be excluded. I, for

one, much prefer dialog like [Laura] "What do you think of New York, Mr. Carter? Isn’t it exciting?"

— [Dr. Pippin Carter] "I hate it.

It’s crowded, it’s noisy, and you Americans have no concept of how the class

system is supposed to work. You go around treating each other like equals,

which I find very distasteful." Or: [Dr. Olympia Miklos] "You are wise to carry a magnifier, my

dear. You miss so many of the good things if you don’t look close enough.

Imagine never seeing pores, or lice, or fungus spores!" Sure, this

has nothing to do with the plot as such, but really, The Dagger Of Amon Ra is all about its characters, and it is here, certainly not in the ugly

twisted contortions of the plot, where the game really stands head and

shoulders above its comparatively bland predecessor. Of

course, all these characters are every bit as stereotypical and

clichéd — I think Balfour and Mandel specifically made a point of them

being clichéd, so as to keep strictly in line with the first game — but

the difference is that now they talk funny, and sometimes they talk funny and smart at the same time. The new

French sexy tart, Yvette Delacroix, gets ten times as many lines as did Fifi,

the French maid, in The Colonel’s

Bequest, and you get to be both disgusted at her character and feel some actual pity for her

plight as her story unfolds from its uncouth beginnings to its gruesome

conclusion. The «aristocrats» are all comically snobby, yet even the above-mentioned

Dr. Pippin Carter (obviously named after and loosely based upon Howard

Carter, the discoverer of Tutankhamun’s Tomb) occasionally gets the chance to

deliver a snarky, insightful observation on life that’s worth mulling over.

The Museum’s Security Chief, Wolf Heimlich, is perhaps the single most

over-the-top parody of a classic Imperial German militarist ever designed for

a video game — or, at least, should be somewhere in those ranks ("NEFFER point a veapon at me, Fraulein Bow!

My highly trained reflexes could kill you in three seconds if I vanted to!

THREE SECONDS!"). Only Laura’s potential love interest, the

stevedore Steve Dorian, is about as boring as a splash of paint on the wall —

but I suppose that was at least partly intentional as well, as there was

probably some deep meaning implied in the fact of Laura getting the hots for

the single least explicitly «interesting» member of the party. There

is definitely a bit of a social angle to the game as well: much of the plot

revolves around the idea of the Dagger of Amon Ra unscrupulously smuggled out

of its native country (Egypt), and of certain individuals’ brave

anti-colonial struggle to restitute it. That angle is clearly handled with a

bit too much humor, crudeness, and political insensitiveness to be acceptable

for today’s mainstream values — but in the game’s defense, let it be said

that Mandel and Co. apply pretty much the same parodic standards to each and

every one of their characters, be it a snub-nosed, elitist British

archaeologist with clear ideas on racial superiority, or a snub-nosed,

elitist, European-educated Egyptian bourgeois with equally clear ideas on a

different kind of racial superiority. The game lets you in on the eternal

debate about the ruthlessness of British and American colonialism, but

declines from taking sides — which is, perhaps, for the best. The Dagger Of Amon Ra’s main purpose

is for you to have fun, not raise your level of awareness; but if you do want to profit from the sensitive

topics it lightly touches upon in order to raise that level, you are most

certainly welcome to try. The

game does go somewhat over the top in its anachronistic depiction of Egyptian

neo-paganism (today usually known as «Kemetism»), presenting all

(both) of its Egyptian characters as comically over-the-top

reconstructionists of the cult of Amon Ra at a time when genuine «Pharaohism»

was typical of a small freakish minority, as opposed to the more generally

Arabic- and Islamic-minded independence movement. It is clear that Mandel and

Co. made quite a bit of research into Egyptian mythology and history while

writing their dialog for the game, but much of that research seems to have

been superficial — to the extent that it is hard for me to tell, when one of

the characters says stuff like "I

do not understand your meaning. Perhaps it is the English... it is such a

curious language... not as clear as Egyptian", if that line is

supposed to be taken seriously or tongue-in-cheek, considering that «Dr.

Ptasheptut Smith»’s native language could only have been Arabic, and that

even if he did go to the trouble of

learning to speak Ancient Egyptian, he would have had serious trouble

perceiving it as «clear». Then

again, Mandel’s writing style is always complex: over and over again, real

and accurate information on the reality of Ancient Egypt is interspersed with

intentional humorous nonsense and gibberish, mixing admiration for the

culture with merciless lampooning, so I would rather honestly refrain from

pronouncing any strong judgement on anything that might superficially feel

«ignorant» or «offensive» in this game, and just relax and enjoy the comedy

instead. In

any case, let us just mark the inescapable fact that the dialog — at least in

those parts where it does not explicitly concern the main storyline of the

game — is a huge improvement over The

Colonel’s Bequest; that the plot of the game, on the whole, makes even

less sense than it used to; and that, once again, it really doesn’t matter as

long as you get your laughs, your atmosphere, and your «edutainment» value. |

||||

|

The puzzle system is where The

Dagger Of Amon Ra shows the most continuity with its predecessor. Just like The Colonel’s Bequest, it dumps Sierra’s classic point system in

favor of certain sets of actions you need to perform in order to unlock the

«good» ending of the game (one in which Laura manages to stay alive, find the

Dagger, and properly identify the murderer). These actions involve getting

useful information from the surrounding NPCs, collecting a large bunch of

potential evidence from crime scenes, and gathering various visual clues all

over the museum. However, unlike The

Colonel’s Bequest, you do not get any actual «rankings» — what you have

to do at the end is be able to correctly answer a number of questions and own

a certain amount of corroborating evidence in your possession; failing this,

Laura may meet a grim end, and the Dagger may never return to its rightful

owners. (The «bad ending» of the game is still well worth getting, though —

just about every single character meets a different fate due to Laura’s

blunders!). As

before, this means that you can essentially all but sleepwalk your way

through the game, for instance, spending most of your playing hours just

admiring the various exhibits in the museum while time slowly marches on and

people get murdered one after another without Laura paying any attention

whatsoever. A much larger part of the action this time is tied to specific

time windows — by failing to be in the right place at the right time, you can

miss some crucial events or some useful chances to extract information from

people when catching them red-handed. This is, however, not a problem, since

(a) most of the time, the blame is on the player for failing to properly

analyze a clue or to explore each area as thoroughly as possible once the

game moves into the next «Act»; (b) in this way, it adds to the replayability

factor, as there almost inevitably will be interesting, and sometimes funny,

things that you will have missed on your first playthrough. You do have to

work quite hard to be on the very top of your game — and there is nothing

wrong about not being pampered all the way through. What

is a problem is that the lack of a

point system, just as it did in The

Colonel’s Bequest, does not properly allow you to track your progress.

You can talk to almost every character on a number of subjects, and this time

around, their answers will be more informative, more diverse, and/or more

hilarious than they used to be — but you have no way of knowing which of the

answers were «formally» useful to you and which ones were just decorative,

and this is particularly frustrating given the inconvenience of the dialog

interface: every time you have to ask somebody about something, you have to

pull out your notebook, browse to the appropriate topic, click on it, read

the character’s answer, and then repeat the process, which is thus quite

time-consuming compared to the more standard dialog trees to which we are

used in modern adventure and RPG games. So, even if talking to people is

typically more productive and entertaining this time around, it actually

becomes even more of a chore than it used to be. In terms of actual «puzzles», the game is a bit more

challenging than Bequest, at least

in its first «Act», where Laura has to come up with various strategies in

order to achieve her objectives — the most difficult of these involving

getting herself into her first speakeasy and finding an official dress for

the reception at the Museum. They are not too

difficult, though, as long as you remember to thoroughly explore your

environments and regularly hop from one place to another, as people and

objects sometimes change places after you have completed certain other

actions. Personally, I don’t remember getting stuck for a long period of time

anywhere — I do remember missing

stuff, though, and even today am not 100% sure that I have actually uncovered

every secret conversation or every individual clue in the game

(perhaps I’m just too lazy to read through the entire transcript of the game

which is now, of course, easily available on the Web). In classic old school Sierra fashion, there are some

dead ends in the game — all of which come to haunt you for its last «Act»,

when the game suddenly turns from a suspenseful, but rather leisurely and

relaxed process of detective exploration into a frenetic cat-and-mouse chase

scene. In The Colonel’s Bequest, the

murderer always manifested oneself as an unseen, hidden presence, watching

you from the shadows, liable to make an unexpected move every now and then

but never ever stepping out into the open. In The Dagger Of Amon Ra, the last section of the game becomes an

exercise in survival horror, where you have to take quick decisions

concerning your own safety — and, unfortunately, some of these decisions depend on your possession or lack of

objects that may have been collected earlier in the game; if they are not in

your pockets by now, tough luck as you are going to die in one of the

inventive half-dozen ways of dying. At least a couple of these are very absurd and moon-logical, most

importantly the one bit where you have to offer your temporarily handicapped

boyfriend one of your useful finds in order to prevent him from stepping on a

nail and dying (!). Needless to say, some of those sequences could have been

designed a little better. But I wouldn’t call these decisions too catastrophical. In fact, the game really only gets seriously bad — as opposed to «tolerable» — in

its challenges at the very end, when you are supposed to identify all the

murderers and match the corresponding motives from a large, and largely

useless, menu of choices during the Coroner’s inquest. The problem there, in

addition to you never knowing which particular objects you have to be in

possession of in order to corroborate your answers, is that the menu options

are quite ambiguous, particularly in the «Match a motive» part, and even if

you have managed to reconstruct the

chain of events reasonably well in your mind, you may easily check the

«wrong» box despite the answer being quite acceptable (e.g. the difference

between «Fear», «Jealousy», «Thrill», or «Revenge» as a motive is not always

clearly understood). The entire inquest just happens to be very poorly

designed, and I think that Balfour and Mandel acknowledged as much in some

later interviews on the game. From this point of view, the final scoring in The Colonel’s Bequest, where the AI

simply evaluated your performance on its own, was actually superior — at

least you had no chance to fuck things up at the end due to poor designer

work after doing everything right throughout the game. In other words, the chief flaw of The Dagger Of Amon Ra is the one it

shares with its predecessor, despite being designed by an entirely new crew:

both Laura Bow games pretty much suck as «detective» games. You have to sweat

the shirt off your back to discover every clue — only to learn at the end of

the game that you didn’t really need half of them and cannot put the other

half to truly good use. You have no way of influencing the chain of events;

and many of your conclusions will still be based on intuition rather than

strict, logically flawless deduction. The back story that you uncover will be

completely and utterly absurd, rife with plot holes and stupid senseless

crimes committed by people who are supposed to be cunning criminals. In a

way, The Dagger Of Amon Ra feels

even more like a parody on an actual detective story than Roberta Williams’

take on the genre — hers was, at the very least, a fairly simple tale where

the characters’ motives were clearly defined. Here, the level of absurdity

totally blows the roof off the house — and the only salvation is that, in all

honesty, I have never ever in my mind really thought of The Dagger Of Amon Ra as a «detective» game. Instead, all of its

charm — maybe even all of its genius

— lies in a completely different dimension. |

||||

|

Both the first and the second Laura Bow games mainly get you

through the «feels» — and this is where the difference between a Roberta

Williams game and a Josh Mandel game really makes itself palpable. The Colonel’s Bequest, as I wrote

earlier, based its feels largely on a conflict between the light and the

dark, the old and the new, the progressive present and the conservative past

— the game loved its references to the Jazz Age not by themselves, but in

contrast to the 19th century ghosts of the old plantation house. It was

really all about chillin’ to a Scott Joplin rag in the fancy billiard room of

the house, then stepping out into the creepy darkness of the swamp and

getting swallowed by an alligator, just to be reminded that Mother Nature does

not think all that much of human progress in the industrial era. The Dagger Of

Amon Ra still has some of that «contrastive» spirit, but since the entire game

takes part in the Big City, there is hardly any space here to go on with the

mystical tug of anti-civilizational forces. There is enough space, though, to

offer the player two different atmospheric environments — which do not enter

into mutual conflict all that much, since they are essentially separated from

each other by the chronological line between «Act I» and the rest of the

game. In fact, emotion-wise it’s almost as if you were offered two completely

different games: «Southern Girl Arrives In New York City» and «Gee But The

Museum Is A Creepy Place». There is a bit of continuity between the two, but

ultimately it’s rather hard and strenuous to imagine a smoothly running,

logical plan that would derive the second one from the first. Which is not a

tragedy — in a way, it’s like you’re getting two separate stories for the

same amount of cash. Of these two stories, my personal favorite is

unquestionably the first one. I love New York, Josh Mandel loves New York,

and I admire Josh Mandel’s lightweight, satirical, but loving portrayal of

New York in one of the most fascinating and exciting periods of its

existence. We don’t get to see too much of it, but we do get to explore

several different locations — the docks, the police station, the Chinese

laundry, the newspaper office, the speakeasy — each of which has a little

spirit, reflected in the beautiful art, the appropriate music, and in

Mandel’s snappy dialog. As you travel back and forth between these locations

in the exact same grimy taxi cab, you are constantly reminded of the day and

age you have been transported to (e.g. Rocco, the taxi driver: «Be careful of the sticky spot on that

seat! I’m always taking that 6-year old Asimov kid over to his parents’ candy

store in Brooklyn. He likes to read science fiction pulps and lick lollipops

in the back seat. Intelligent kid, but kind of messy» — amusingly, this

is a fairly historically accurate depiction) — and overall, what with all the

random NPCs walking about and the occasional short dialogs you can have with

accidental bystanders, this version of New York City is about as alive as it

could be in a 1992 adventure game. As in The

Colonel’s Bequest, most of the people around you remain stereotypical;

the difference is that Mandel provides them with individual personalities as

well, successfully mixing tropes and clichés with sarcasm and wit.

Some people today might cringe, for instance, at the allegedly «racist»

depiction of Lo Fat, the owner of the Chinese laundry (starting with his very

name, which I personally think is hilarious), but stick around his laundry

long enough and you clearly get to understand that the funny-talkin’

mock-Chinese NPC is actively selling his stereotypical Fu Manchu image to his

loyal customers as part of a wickedly cunning commercial strategy. (Try to

look at the «Chinese» characters behind Lo Fat’s back and you get a brutally

honest reply: «They’re not really

Chinese characters. Lo Fat displays them to give himself an aura of

authenticity... since he was actually born in Newark, New Jersey»). The New York around Laura is full of such characters

— brimming with various aspects of life, from street wisdom to snarky humor. The

kids outside Lo Fat’s laundry, getting busy incinerating ants with a magnifying

glass, represent the city’s spirit of survival («It’s a nice day, isn’t it?» – «I dunno...» – «Well, there’s not a

cloud in the sky and the sun is shining!» – «I guess. Makes the ants light

quicker, that’s for sure»). The Irish sergeant at the police desk (who

sometimes behaves as if he were really Scottish) is the classic «good-natured

cop suffering from bureaucratic pressure». The lesbian flapper in the back

room of the speakeasy (voiced by Sierra’s creative genius Jane Jensen, no

less) reminds us of the exciting «moral relaxation» of the decade.

Seriousness, humor, sarcasm, and absurdity produce a mix that feels more

influenced by the likes of Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton than F. Scott

Fitzgerald or Virginia Woolf, and provides us with one of the funniest and wittiest love letters to the old

(but once very, very young) spirit of New York in a video game. Skip ahead to «Act II», though, and all of that is

largely gone. As Laura finds herself swallowed up by the vast expanse of the

Leyendecker Museum, not to be released until the very end of the game, by

which time she has lost all agency anyway, she becomes locked out of the

semi-realistic, semi-parodic New York and enters a whole new dimension — one

in which all of the surrounding characters suddenly become small and

insignificant next to the sprawling and looming heritage of human and natural

history. The Leyendecker Museum hosts pretty much everything, from mammoth

and dinosaur fossils to Renaissance paintings to medieval armour to enormous

Ancient Egyptian exhibits — it’s really like the Metropolitan and the AMNH

all in one — and, as befits a classic horror story, it behaves as a huge,

autonomous organism with a life all its own, so much so that it actually

seems futile to look for the murderer, when it is clear that the entire

series of murders has been orchestrated by the Museum itself. With dead

bodies trapped inside sarcophagi, cast in plaster like ancient Greek statues,

dismembered in order to look like exhibits in the Anthropological section, or

implaed on Mastodon tusks for authentic reproduction, it is once again as if

the ghosts of past history have rallied themselves against their foolish,

greedy, and brainless descendants. To me, though, this second part is a bit of a

letdown, possibly because it is a bit too

sprawling. Unlike the plantation house and environment in The Colonel’s Bequest, the Leyendecker

Museum is too large and disjointed. It is confusing and difficult to

navigate; exhibits seem to be arranged completely randomly, with dinosaur

fossils next to medieval tapestries and medieval tapestries two feet away

from Egyptian mummies. Strangely, the game also places a huge emphasis on

«mock-edutainment»: most of the exhibits are accompanied with detailed

descriptions, some of which are quite accurate (e.g. information on all the

1st century Roman emperors when you look at their busts in the atrium) and

others are there just for the joke (e.g. the silly stories about the

Hottentot and «Poppentart» tribes in Dr. Carrington’s office). I fully

appreciate the idea — after all, everybody with a good IQ should be able to

distinguish between truth and fiction in these depictions on their own — but,

unfortunately, all the humor also serves to detract from the creepiness /

spookiness of the murders. Perhaps that was the gist of it — not let the

player be creeped out by all the seemingly random murders by making the whole

situation overtly grotesque, like a set of Mortal Kombat fatalities — but this is not an ideal combination

of humor and horror. (Something like Gabriel

Knight would manage this mix a lot more successfully). Where the first act of the game clearly stated I

LOVE NYC, the rest of it hardly makes any clear statements at all. For sure,

it’s got some great jokes, some cool red herrings, and some impressive signs

of dedication — like the medieval armour exhibit, where, for, like, no reason at all, you can just hang

out for about thirty minutes, reading all the detailed descriptions of

various helmets, cuirasses, and banners, trying to sort the historical facts

from the pseudo-historical jokes. As a collection of all sorts of random

jokes, witticisms, and unpredictable twists, the Museum sequence is great;

but it is nowhere near as coherent and reasonable as Laura Bow’s adventure in

The Colonel’s Bequest. You

generally live here in anticipation of seeing what other crazy twist of fate awaits you behind your next door — it’s

more of an Alice In Wonderland vignette-style adventure than a

Gothic-influenced murder mystery. The only thing missing, really, is a potion

bottle that says DRINK ME and lets Laura Bow squeeze through the keyhole of

her next locked door. (Those huge alcohol vats in the basement which even

have entrapped unicorns and King Graham itself stored there take us as close

to that reality as possible, though — I know these things are really designed

as Easter eggs, but they still fit in rather naturally with the surrealism of

the environment). When the final act comes along and the environment

changes from potentially dangerous to a real active threat, the effect is not

nearly as strong as it would eventually be in Roberta’s Phantasmagoria — precisely because the game has been way too

funny for most of its duration in order for us to begin truly fearing for our

life at this point. Oh, some Grim Reaper clown with a mace just clubbed Laura

to death in the hallway? Well, didn’t we just read «Death is a natural part of life, so when your time comes, it’s best

to accept it and go out gracefully» on a bottle of snake oil? It’s a

little inconvenient, sure, that all these clubbings get in our way of beating

the game before bedtime, but other than that, it still kinda feels like Monty

Python. It doesn’t help, either, that when you run into the sinister Cult of

Amon Ra in your attempt to escape from the murderer, the cultists are heard

to be chanting "RA RA AMON RA... RA RA SIS BOOM BAH...". You’ll die

of laughing before you get a chance to die of anything else. This is not to say that the entire time spent inside

the Leyendecker Museum is not enjoyable as such. It is simply skewed way too

heavily on the humorous side for a game that is formally a suspenseful murder

mystery — as opposed to something like Freddy

Pharkas, for instance, which also had a bit of a detective plot, but its

chief purpose was to be a video game equivalent of Blazing Saddles and the game never for one moment pretended that

it was something different. Meanwhile, The

Dagger Of Amon Ra relates to The

Colonel’s Bequest a bit like Dracula:

Dead And Loving It would relate to 1931’s Dracula, especially if it were advertised as the «true sequel» to

the 1931 movie. True, it totally annihilates the original game in terms of

quantity, quality, and depth of its dialog and characters — but does so at

the expense of completely mutating the original’s game genre and atmosphere.

And it is also not a very good thing that there is not a single moment,

whenever I’m playing it, when I am not

feeling a little sad about being taken out of the good old lovable New York

City and stuck into this weird out-of-time place with no connection to

reality whatsoever. That said, I do not want to complain too much, because even if Mandel’s

creative genius does seem a little misapplied in the game, it’s still genius.

Exploration in The Colonel’s Bequest

was merely okay — rather perfunctory and rarely rewarding, as the text was

usually laconic and bland and the game’s atmosphere was more due to sound and

visuals than words. Exploration in The

Dagger Of Amon Ra is tons of great fun, as pretty much every single object

either reveals a juicy bit of historical trivia or a joke (as a rule,

genuinely funny). Even if you are not scooping up a lot of murder-related

clues, you are still getting

actively rewarded for trying to look at or touch just about anything in plain

sight — or trying to talk to various NPCs about stuff like charcoal, carbon

paper, or an electric bulb in your possession. It’s not particularly

«atmospheric», but it keeps you on your toes and never lets the game slip

into boredom — particularly if you are playing the «talkie» CD version with

voice acting, the perks of which we shall get around to discussing fairly

soon. |

||||

|

Technical features |

||||

|

On

a purely visual level, The Dagger Of

Amon Ra reflects Sierra’s general standards of quality, but I wouldn’t

call the game exceptionally stunning or unique. Naturally, the main interest

here should be directed towards «Act I» and its depiction of New York — both

the exteriors and interiors of which look credible, but not particularly rich

in detail, almost as if the artists responsible were on a strictly regulated

time basis. The hand-painted backgrounds are stylish, yet somewhat

perfunctory, and you probably won’t be spending too much time pausing your

game just to take in the scenery. Some interiors are just downright

disappointing — like the speakeasy, for instance, which looks more like a

quickly put together imitation for some high school theater play rather than

a properly authentic recreation of a hustlin’ and bustlin’ environment.

Overall, Dagger’s New York looks

just a little... frugal, perhaps, next to what we usually think about the Big

Apple in the 1920s. Nice and colorful, but I think it’s safe to say that it

comes more alive in this game through text (and speech) than visual

impressions. The

same, slightly Spartan, approach is chosen for most of the interiors in the

Museum, but in this instance, the artistic approach works better — for one

thing, the emphasis is on showing the Museum off as a generally cold,

inhospitable place, not particularly welcome for its guests; for another,

cluttering the Museum too much

would have seriously inconvenienced the gameplay, much of which is focused on

exploring every nook and cranny. On the other hand, the visual contrast

between all of the Museum’s different locations — the dinosaur exhibits, the

Egyptian room, the Old Masters’ gallery, the medieval armor hall — is

presented quite sharply, emphasizing the somewhat surreal and thoroughly

unpredictable nature of this weird place you’re in, disjointed as it is from

any sense of reality, even a museum-related one. When

it comes to people and animations, most of the character sprites reflect

Sierra’s typical early 1990s ugliness — and it does not help that, in an

attempt to make at least a slight approximation to 3D, sprites get

progressively bigger or smaller depending on their proximity to the player;

«bigger», in this particular case, just means «more pixelated». It’s even

worse because the sprites contrast in such an ugly manner with the close-up

portraits of the characters, which, on the other hand, represent the highest

level of Sierra art to that particular date — all the faces are realistically

painted, skilfully animated, and let you know a whole lot more about the

personalities behind them than the perfunctory sprites. Perhaps there is not

quite enough continuity in Laura Bow’s own image from the first game (where

she had a fairly «downhome» aura) to the second (where she is portrayed a bit

more like a stereotypical «Southern belle» type), but there’s nothing to

prevent us from thinking that she might have simply «upgraded» her class for

the important visit to New York City. Another

area where the game certainly improves on the first one is the amount and

quality of the close-ups — this time, for instance, you are able to see the

«gruesome» murders up close, with each body arranged in its own uniquely

macabre fashion and with clues available for visual inspection, not just

appearing as results of blindly typing in «search the body» or the like. All

these «fatalities», though certainly not of the Mortal Kombat variety (this is a family-friendly game, after

all!), nicely support the game’s dark humor theme and are sure to procure at

least some players of the young adult variety a few delicious nightmares.

(And they definitely succeed in making us understand the concept of «the Art

of murder» with their chilling closeup of Yvette Delacroix’s «arrangement»!). On

the whole, though, I think that pretty (or pretty gruesome) pictures will not

be the first thing people are going to remember about this game —

particularly if they have the full (CD-based) version of it, allowing to

complement the visuals with a full voice acting cast... which is probably the

most enticing and bizarre part of

the game’s technical aspects. |

||||

|

The original floppy disk version of the game from 1992, which I

vaguely remember I played first, did not have any voice acting, thus having

to rely exclusively on the music to set up the aural atmosphere; and, much

like the visuals, the music was really quite good, but not particularly

outstanding. Naturally, for the first «Act» principal composer Chris Braymen,

a Sierra veteran from the days of King’s

Quest V, wrote several tracks reflecting the spirit of the times: some are

distinctively New Orleanian (‘Laura’s Theme’, playing during her introduction

and reprised as a piano rag at the beginning of each new «Act»), while others

are decidedly more «urban» in nature, including the happy Charlestons and

luscious waltzes playing down at the speakeasy. Chinese-style music is

expectedly playing at Lo Fat’s; a grumbly military march expects you at the

police station; and a Scott Joplin-derived theme is chirping away in the

office of Sam Augustini, Laura’s newspaper boss. It’s all lightweight, but

fun; do not expect the full impact of something like The Sting, but do expect to get all the moods set up just right. Similarly,

at the Museum, when you are abruptly ushered out of your specific

time-and-place window and into a totally surreal and unpredictable environment

where entourages change almost a random, the music usually fits the setting —

there is a «mystical» Mid-Eastern theme floating through the Egyptian exhibit

room, for instance, while Laura’s general travels through the museum

corridors are accompanied with suspenseful incidental music, reminiscent of a

1950s or an early 1960s soundtrack to some thriller or noir. Individual NPCs

are sometimes provided with their own appropriate themes (Yvette Delacroix,

rather predictably, gets jazzy «strip club muzak» to represent her character);

and the soundtrack gets appropriately sped up and frenzied during the mad

chase scenes in the last «Act», though, due to limited budget and ambitions,

the music still remains somewhat cartoonish as compared to, for instance, the

nearly-movie-quality musical arrangements for Phantasmagoria several years later. At

some points, you’ll probably want to turn the music off, because the design

is not always perfect — the lengthy second «Act», for instance, which you

mostly spend hanging out in the huge Museum lobby, chatting up and

eavesdropping on the guests, is accompanied throughout by the same ‘Museum

Waltz’; by the time you’re through with the action, you’ll probably have it

ringing in your ears on a permanent basis something worse than do you believe in life after love. For

some reason, nobody came up with such obvious ideas as varying the soundtrack

for a single environment, or using the theme only as an introduction, or at

least setting up lengthy pauses in between the reiterations (as they would do

in a Shadow Of The Templars or a Baldur’s Gate game later). For

the 1993 CD release of the game, the music did not change much — but,

following in the footsteps of King’s

Quest V, the developers threw in a «mini-song» performed at the speakeasy,

a bit of novelty vaudeville entitled ‘I Want To Marry An Archaeologist’

which is quite hilarious but, unfortunately, not quite original, being

strongly based, both musically and lyrically, on Erika Eigen’s ‘I Want To Marry A

Lighthouse Keeper’, well known to every fan of A Clockwork Orange. It is not totally out of left field, though —

the song does remind players of the

walk-like-an-Egyptian «Tutmania» ruling over the Western world ever since

Howard Carter’s discovery of Tutankhamun’s Tomb in 1922, and its reflection

in all sides of life including popular song and dance. And it’s certainly

better that they used ‘Lighthouse Keeper’ as a base reference point, with its

already persistent 1920s atmosphere, than, say, trying to make a meta-spoof

on Steve Martin’s ‘King Tut’ or something equally obvious (though, as we have

already established, The Dagger Of Amon

Ra can be quite friendly to anachronisms, what with the RA RA SIS BOOM BAH thing and

everything). Much

more odd than the music, however, was the voice cast assembled for bringing

the world of Laura Bow as close to life as possible. In 1992, Sierra was as

of yet unaccustomed to getting professional actors to voice their games,

other than maybe an occasional guest star or two (like inviting Gary Owens as

general narrator for Space Quest IV);

and whatever budget the studio may

have had at the time was all targeted towards Roberta Williams’ main project,

King’s Quest VI. Thus, pretty much

everything had to be voiced by the Sierra staff itself, like they did for

previous games starting with King’s

Quest V in 1990 — the exception being that this time, the amount of

dialog to be recorded was simply enormous, the cast of characters so large

that multiple NPCs had to be voiced by the same «actors», and most of these

characters were supposed to be so clichéd and stereotypical that the

«actors» were pushed hard to «over-act», sometimes with hilarious and

sometimes with embarrassing results. In the end, you may like the acting or

you may hate it, but you’ll probably never forget it. First,

the good news: Leslie Wilson. A lowly staff member at Sierra (either the

receptionist or a proofreader and text editor, I honestly forget which), she

was drafted along with everybody else to do some voice work, and after she

managed to fake a properly sexy French accent for Yvette Delacroix, Balfour

offered her to take on the roles of both Laura (which required a Southern

accent, of course) and the game narrator, which required... the ability to

entertain and charm the player by reading aloud a lot of boring or humorous

text, ranging from «you see a street

lamp» to «death is a natural part

of life». Apparently, Leslie Wilson emerged out of this game as Leslie

Balfour, and I can see, uh, hear

why — as the Narrator, she has an almost nightingal-ish purity to her voice, with

a slightly educational and moralistic tinge as would befit, say, a recent

graduate of some Finishing School for Young Ladies. As Laura, her Southern

accent is clearly fake, but she wiggles her way out of it by portraying Laura

Bow as, you know, a provincial type trying to adapt to a more New York type

of speech — with a nice degree of naïve innocence, inborn intelligence,

and independent, proto-feminist stubbornness. Sometimes she falls prey to

overacting (particularly in her romantic dialog with Steve Dorian), but

usually she is spot on, and pretty much the

main reason why you should give a try to the voiced version of the game. As

for the rest of the cast... well, probably the best I can say is that it’s

much easier to tolerate if you take the entire game for a spoof, which it

more or less is. Balfour and Mandel themselves take the lead, with Balfour alone

having to generate the snotty aristocratic Englishness of Dr. Pippin Carter,

the proverbial Teutonic militarism of Wolf Heimlich, and the New Yawk street

rat nature of Ziggy the stool pigeon — pretty impressive how he pulls off all

three, but it’s really all about pure parody. Meanwhile, Mandel totally

misses the boat with Laura’s beau Steve Dorian, whose voice, for some reason,

was imagined as a deep, rumbling bass, despite being totally incompatible with his sweet tenor appearance. Considering

that bass is not Mandel’s natural tone of voice, the result is doubly

grotesque; throw in Leslie’s rather clumsy handling of her love lines, and

the entire romance angle is blown to bits. John Smoot gives us an equally

unconvincing Detective O’Riley, who sounds more like a whiny banking clerk

than an intimidating police chief; and programmer Cynthia Swafford makes a

completely cartoonish, poofy Countess Waldorf-Carlton who sounds like she’s

on a constant dose of helium. Only Kelli Spurgeon as Dr. Olympia Myklos, the

Greek lady with a penchant for all things macabre, does a proper job, I

believe. Unfortunately,

even the idiosyncratic success of Leslie Wilson was not enough to turn her

into a voice acting star for future games — and the dubious «talents» of the

other «actors» showed Sierra, once and for all, that in the future they would

have to spend more money on some proper

talent if they did not want to end up as the laughing stock of a new era of

video gaming. Above all, this was realized by Jane Jensen (who is also here,

by the way, voicing the rebellious lesbian flapper in the changing room of

the speakeasy — in her usual nasal, sneery tone), who, fortunately, would

insist on a real Hollywood cast for her own Gabriel Knight next year (could you imagine the horror of having

Bruce Balfour or Josh Mandel voicing Gabriel Knight instead of Tim Curry?).

But, like I said, the overall eccentric and comical nature of Dagger at least partially redeems all

the negative consequences of having such a limited budget. |

||||

|

The general gameplay of Dagger

follows the standard patterns of Sierra’s point-and-click interface of the

early 1990s. Due to

Laura’s special ability to question the NPCs on various subjects, this was, I

think, the first game to split the traditional «Talk» option into two

varieties — the exclamation mark (!) takes care of «regular» conversations,

usually consisting of very minor dialog exchange, while the question mark (?)

leads to actual questioning (with a rather cumbersome notebook-based menu of options

whose logistic inconveniences I have already mentioned earlier); the same

principle would later be borrowed by Jane Jensen for Gabriel Knight and used in a few other games as well. Just

like it was in The Colonel’s Bequest,

Laura can die in half a million different ways — some of which are quite

honestly predictable, like when trying to cross a busy street, or spending

way too much time near the intoxicating alcohol vats in the Museum’s

basement; others are fairly mean (for instance, recklessly opening the trunk

in Dr. Myklos’ laboratory without knowing beforehand (!) what specific sort

of danger lurks inside) and require you to save your game before attempting

to perform any action that could be even vaguely

risky. But that’s Sierra for you — when they write up a small death vignette,

they simply want to make sure you don’t miss it («death is a natural part of life», remember?). Worse is the

presence of several dead ends, all of them near the end of the game — if you

have a save file right before Laura’s investigation of the last murder, this

won’t be too much of a problem, but if not, tough luck. In

terms of overall gameplay, an interesting innovation, carried over from The Colonel’s Bequest but seriously

expanded, is to have the NPCs strut all over the Museum, rarely sticking in

one spot but more frequently moving from one hall to another, as if having

nothing better to do. Ironically, even though this was probably done for the

purposes of adding extra realism, the result is rather goofy — the characters

spend the entire night pointlessly roaming around with no apparent purpose,

waiting to be killed off by the murderer. If you happened to be locked up inside a large museum for an entire

night, your most realistic purpose would probably be to find yourself a cozy

corner to catch some sleep... not for those

guys, though. It also makes it fairly inconvenient to catch any one of them

for some questioning — sometimes they have a habit of disappearing

completely, only to re-emerge after you have given up and switched to some

other purpose. Admittedly, it’s still engineered a little better than

Revolution Software’s Virtual Theatre games, in which interacting with moving

characters was a true logistic nightmare, but even so, still serves as a

classic example of that road to hell, paved with good intentions. The

only other thing worth mentioning is the copy protection system — only used

for the floppy version (the CD edition, like King’s Quest V and other early games from the CD era, did not

have one, since back in 1992 developers were still naïvely thinking that

CDs could not be copied), it regularly required you to prove your «knowledge

of Egyptology» by matching the image of an Ancient Egyptian deity with one of

its common attributes, only possible either if you had the manual or already

were a big fan of Egyptian mythology and visual arts. The move was stylish

and ingenuous, but it was a little

annoying to have to repeat it at the beginning of each «Act»... also, it

really wasn’t much of a copy protection, as I distinctly remember rather

quickly guessing all the right answers while playing my own pirated copy,

without the slightest hint of a manual. Overall,

the interface and gameplay of The

Dagger Of Amon Ra may be said to respect the legacy of The Colonel’s Bequest: make things

just a bit aesthetically different from the «regular breed» of games to make

the experience a little more stylish and exquisite. The actual results,

however, are less satisfactory, both for reasons of convenience (the

unnecessarily time-consuming and clumsy notebook system of questioning) and

taste (even the clock, appearing in a corner of the screen to mark out time

after you have completed some significant goal, looks primitive and

perfunctory compared to the nicely ornamented wooden frame in The Colonel’s Bequest). Despite

suffering from being made three years earlier, The Colonel’s Bequest is, on the whole, more stylish in its general mechanics — although this is, really,

a very minor point. |

||||

|

Although I am probably alone in preferring, on the whole, the first Laura

Bow game to the second one, The Dagger Of Amon Ra still has plenty of

redeeming qualities to count as an overall enjoyable success. Its major

problem, I think, is the lack of internal consistency — it tries to be as

much of a «Roberta Williams-type» mystery game as a «Josh Mandel-type» lovingly

comic spoof, and the two sides frequently contradict each other; the result

is something like The Colonel’s Bequest meets Freddy Pharkas, and

it is hardly a surprise that I rate both of those higher than The Dagger Of

Amon Ra, which, due to this conflict of interests, is neither as

suspenseful or as funny as it would hope to be. The New York part of the game

is almost magnificent — the vistas, the puzzles, the dialogs, the humor all

come together in a stylish atmospheric experience; but with the lengthy Museum

sequences, the game becomes a completely different entity that leaves me

frustrated almost as often as it gets me excited. Still, there is no denying that in the Leyendecker Museum, with all

of its surrealist diversity and dark, creepy secrets, Balfour and Mandel had

created a fairly unique environment; and especially Mandel’s manner of mixing

in true historical and cultural facts with elements of pure parody was a pretty

fresh touch (later on, Sierra would explicitly adapt the principle to its educational

Pepper’s Adventures In Time project, where kids could conduct actual

checks on which parts of the game were historically true and which ones were

intentionally anachronistic — this, however, is an adult-oriented

game, and you are supposed to weed out the chaff on your own). Throw in the uniquely

wonderful presence of Leslie Wilson, the likes of whom would never again be

seen in an adventure game, and all of this ultimately redeems the game’s many

flaws. As of today, judging by their relative presence on the Web, the cult

of The Dagger Of Amon Ra is unquestionably much stronger than that of The

Colonel’s Bequest — after all, the game is larger, has voice acting, a

ton of irreverent humor, and better graphics (at least technically), so this

is perfectly understandable. It even managed to make an actual personality

out of Laura Bow herself, which Roberta Williams was unable to achieve on her

own. What it did not manage to make was a game that could creep you

out with the same effect as its predecessor, or a game that could make you so

easily forgive and forget the clichéd representations of its

characters or the corniness of its mystery-related dialog. For everything

that’s snappy, snazzy, and awesome about the game, there is something silly,

illogical, and badly worded; The Colonel’s Bequest feels «wholesome»

in comparison to this somewhat messy, disjointed experience. And even so, I

still like it a lot. If anything, messy, disjointed experiences usually give

you a whole lot of points to think about... |

||||