|

|

||||

|

Studio: |

LucasArts |

|||

|

Designer(s): |

Dave

Grossman / Tim Schafer |

|||

|

Part of series: |

Maniac

Mansion |

|||

|

Release: |

June 25, 1993 (original) / March 22, 2016 (remake) |

|||

|

Main credits: |

Programming: Jonathan Ackley, Ron

Baldwin, Dave Grossman, Tim Schafer Music: Clint Bajakian, Peter McConnell, Michael

Land |

|||

|

Useful links: |

Complete

playthrough, parts 1-5 (5 hours) |

|||

|

It is a little unfortunate, in my

opinion, that Day Of The Tentacle

was designed as a sequel to Maniac

Mansion, rather than a completely stand-alone title. Essentially, it

means that without playing Maniac

Mansion first, the player is bound to be somewhat confused by the opening

of the game — who are these green and purple tentacles? how and why are they

connected to that bunch of kids? what sort of history does Bernard have with

the proverbial «mansion»? etc. — not to mention that all the tribulations of

the Edison family work best if you know the backstory. Yet recommending that each player complete

Maniac Mansion first (subtly hinted

at by the designers, who went so far as to include the original title as a

game-within-a-game — see below) is fairly harsh, because while Day Of The Tentacle, especially in its

remastered form, is perfectly playable by anybody even in this day and age, Maniac Mansion remains a museum piece

with outdated graphics and no sound, playable only by game historians and

truly dedicated aficionados. This is particularly unfortunate

because in every other respect, Day Of

The Tentacle is not really a «sequel», but a fully autonomous enterprise.

It was designed not by Maniac Mansion’s

original creators, but by the Monkey

Island co-designers Dave Grossman and Tim Schafer, who first worked with

Ron Gilbert, then took over his duties after his departure from LucasArts —

even though one of Ron’s earlier concepts (involving time travel) was indeed

chosen as the basis for the game’s storyline. The game involves a completely

different roster of playable characters (except for Bernard, who still goes

through a complete character transformation, from a forgettable and interchangeable

nerdy sidekick in Maniac Mansion to

a fully fleshed-out, personality-endowed hero in Day Of The Tentacle). The story itself has few, if any, ties to

the plotline of Maniac Mansion. And

in terms of puzzle design, world-building, story intricacy, witty and funny

dialog, music, voices, and graphics, Day

Of The Tentacle blows its predecessor out of the water — even taking into

account the predictable raising of standards from 1988 to 1993, the boys did

such an outstanding job here that, in quite a few aspects, Day Of The Tentacle has yet to be

bettered by any game that followed it... and perhaps it never will. Of course, this unfortunate little

chain link is only a stumbling block for situations where, for instance, you

want to make a point about video games as an art form to somebody who has

never played a video game before. General players will hardly be bothered

with a little confusion (certainly no more so than all those millions of

people playing The Witcher 3

without ever having tried out the first two) — and, in fact, I am pretty sure

that many of the critics who gave glowing reviews to Day Of The Tentacle upon its original release had never

experienced Maniac Mansion (I

almost wanted to write "had not yet been born in the times of Maniac Mansion", but people might

have a hard time understanding that one figuratively). Yet the fact that so many people who

have actually played the game were willing to bestow upon it the title of the

most perfectly designed adventure game of all time — just check all those

Steam or MetaCritic pages — contrasts quite radically with the fact that,

like most LucasArts titles, it was never a big seller (80,000 copies sold in

16 years, according to a report on Wikipedia — compared to, say, 400,000

copies of King’s Quest 6 allegedly

sold on its first week). And this is understandable, because, maybe more so

than any other LucasArts game, Day Of

The Tentacle is the high point of the studio’s hip, post-modern, wildly

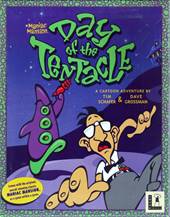

absurdist ideology. You do not need to go past the box cover, featuring a

nerdy guy pursued by a giant purple tentacle, to realize that this purchase

is, perhaps, best suited for those looking for "something completely

different". That it was produced at all, by a subdivision of one of the

major film and game companies of its time, is an impressive testament to an

epoch in video gaming the likes of which we will probably never see again. The good news is that,

following Grim Fandango, Day Of The Tentacle would also be

eventually picked up by Tim Schafer’s studio, Double Fine Productions, and,

more than 20 years after its original release, would receive a major

facelift, allowing old fans to refresh their memories and new fans to once

more breathe in that air of liberty from 1993, enhanced by convenient updates

in graphics and interface. The overwhelmingly positive response to the remake

clearly proved that the game hasn’t aged one day — except for, maybe,

carrying over a whiff of that time period’s adorable innocence. |

||||

|

Content evaluation |

||||

|

In a different age, in a different

environment, in the hands of different... uh, alternately talented people the plot of Day Of The Tentacle, resting on the shoulders of two of the most

tired tropes of existence — «evil monster wants to take over the world» and

«time travel fucks things up» — would have turned into a boring mess.

Actually, the brief introduction sequence, in which Green Tentacle fails to

stop Purple Tentacle for imbibing the radioactive waste flowing into the

river out of Dr. Fred’s laboratory, is

a bit disappointing. It is merely a plot device intended to set things in

motion, but we do not know that yet, and the sheer fact that it is not Ernst

Stavro Blofeld or Emperor Palpatine, but a giant Purple Tentacle thundering

"I FEEL LIKE I COULD TAKE ON THE WORLD!!", is not altogether

reassuring. Anybody familiar with the history of

LucasArts, though, will immediately remember that the studio’s basic

principle is rarely, if ever, to invent entirely new plots, but rather

deconstruct and play with traditional ones in ways that simultaneously mock

their conventions and breathe new life into them. In order to stop Purple

Tentacle from his nefarious activities and ensure the survival of the human

race, our heroes (what heroes? we’ll get to that momentarily) have to go back

in time and prevent his incident rather than neutralize it post-factum. In

the process, due to the fact of Dr. Fred "Stingy" Edison using a

fake diamond instead of a real one, they end up in three different time

periods — the past, the present, and the future — making their task far more

complicated, since now they have to find different ways to power up their

«Chron-o-Johns» (don’t ask) for the return journey; a particularly daunting

challenge for the one stuck in the era of the Constitutional Convention,

though somewhat alleviated by the opportunity of having Ben Franklin sticking

around. The three heroes in question are

Bernard Bernoulli, a nerdy student first introduced in the original Maniac Mansion and now turned

protagonist; Hoagie, an overweight, nihilistic, non-plussed metalhead roadie;

and Laverne, a medical student who’s seemingly breathed in one too many

chemicals. Of these, Bernard is the least interesting character by himself,

more or less a generic blank slate for an inventive nerd — but Hoagie and

Laverne are among the most unforgettable playable characters ever created in

computerland, and, dare I say it, only made possible by the generally whacky

atmosphere of the early software industry. Fortunately for us, the least

interesting character (Bernard) stays in the least interesting time period

(the present), while Hoagie is sent off to remain colorfully unperturbed at

the sights of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, and Laverne is

propelled into the future, where Tentacles have taken over and are now

keeping humans on leashes like the pet poodles they deserve to be. What makes this plot truly outstanding,

however, is not the idea of human history as a gradual evolution from the

Constitutional Convention to the replacement of Homo sapiens by the Tentacle as a dominant species, but the idea

of it as a chain of causes and consequences, one slight tweak at one end of

which will bring on radical changes at the other. Not only do the deeds that

Hoagie and Bernard perform on their end influence the fate of Laverne’s

Tentacle-dominated future, but all three characters can actually use their

stuck Chron-o-Johns to pass objects from one era into another, accelerating

those influences and changes when necessary. This simple, but utterly

unrealistic mechanic could hardly be thought of in a serious sci-fi novel or

movie, but it is perfectly fitting for a video game — and it creates a nearly

limitless sack of possibilities, only a few of which, unfortunately, have

been realized in the actual game (this is not a criticism, though: had

Grossman and Schafer gotten too

carried away with all the fun, the final product would not have shipped

before the dissolution of LucasArts). To be sure, this feels more like a

triumph of algorithmic intellect rather than a showcase of substantial

philosophical depth. There is no strong moral tale told here, and the overall

convoluted web of motifs feels like an outrageous mish-mash of elements from Back To The Future, Planet Of The Apes, and maybe a little

Dr. Strangelove thrown in for good

measure. In other words, Day Of The

Tentacle is still, first and foremost, a LucasArts video game, albeit one

of the very best. But then, complaining about this is a bit like begrudging

the fact that, although the current Olympic champion did set an absolute record for pole vaulting in the history of

mankind, he did not, in fact, clear the Empire State Building. LucasArts

Games were rarely about telling an impressive story; they were always about

breaking the limits for imagination, unpredictability, humor, and

outside-the-box thinking. And in all these matters, Day Of The Tentacle sets such high watermarks that the game still

remains more memorable than many later games with formally more deep and

complex storylines and philosophies. |

||||

|

Many of the puzzles designed for Day Of The Tentacle have long since

passed into legend, and for damn good reasons. This is one of the toughest

LucasArts games to beat without a walkthrough (or a hintbook, if you take the

Chron-o-John back to 1993) — because it takes the base mechanic of Maniac Mansion, where you had to think

your way out of any situation by correctly applying the combined talents of

your squad members, and sends it to the next level by separating your squad

members with the sheer factor of time. Even when you get used to the idea that

your characters can communicate with each other through the bowels of a

spacetime-continuum-disrupting portable toilet — even when you actually get

used to that, the necessity to

constantly switch between characters and have them pass to one another a

variety of objects can remain disconcerting for the most meticulous players.

This is rigorously superimposed over the classic LucasArts logic which you

also have to adhere to at all times — the same logic that makes it perfectly

reasonable that not only can a candy machine hold about eight hundred

seventy-six thousand six hundred dollars worth of quarters, but that a single

living person can fit them all in his pants and then quickly insert all of

them into a washing machine to keep it running for the next couple hundred

years. Makes perfect sense, doesn’t it? I would not necessarily agree with the

popular opinion that all, or even most, of Tentacle’s puzzles are exemplary models of perfect puzzle design.

At least one serious flaw is the lack of direct communication between the

characters once they are separated: in order to have one of them help out the

other, he or she must essentially guess

(on some sort of telepathic level?) what the other one might need in the

future or past. This results in weird experiences where sometimes you feel

like you must do something without

clearly understanding what you need it for. Thus, early in the game it is

obvious that you must somehow

convince George Washington to chop down a cherry tree — because the legend

demands it — but it actually takes putting more than two and two together to

understand how this will benefit Laverne in her state of distress. The puzzle

itself is not too difficult, but you have to find some extra internal

motivation to solve it. Later on, things get progressively more

and more complicated, with Laverne truly getting the short end of the stick —

in order to have her mummy win the Best Hair, Best Smile, Best Laugh

competition, she must receive chrono-stream donations from both Hoagie and

Bernard, as well as make some pretty unorthodox grooming decisions on her

own. Top prize, however, goes to the infamous multi-part Hamster Puzzle,

which would take a very large paragraph to describe (a.k.a. spoil) in detail

— suffice it to say that in order to have the little guy powering up the

engine needed to transport Laverne back into the present, nothing works short

of an entire constitutional amendment that will require every American to

keep a vacuum cleaner in their basement (quote John Hancock: "What’s a

vacuum cleaner?"). Although it would be a stretch to call

the three universes of Day Of The

Tentacle an «open world» (most of the action does, in fact, take place

within one and the same mansion in three different chronological states),

many of the puzzles may be performed in pretty random order, depending on

which of your guys you want to focus on first or last. There will always come

a time, though, when you will get hopelessly stuck in one place and be forced

to move on to the next character, and then to the next, and it does require a

pretty neat ordering of your brain — or, at least, of your notepad — to not

get paralyzed in the ocean of possible (and impossible) choices. Of course,

you will not get overwhelmed with pending quests the way it happens in modern

RPGs, but most of the quests in RPGs are laughably simple anyway: Day Of The Tentacle gives you fewer

things to do, but makes you work really

hard for each specific result. That said, the game lays out its rules

of conduct — harsh, but consistent — quite clearly from the beginning, and

never lets the player down with dead ends, deadlocks, or dead bodies (in Maniac Mansion, there were situations

in which your characters could actually die; Day Of The Tentacle is deathproof all the way). The game plays

out at a leisurely pace, where (after a short while) you can freely navigate

between any of your characters at any given time; only at the very end a drop

of tension is introduced when you have to run circles around the annoying

Purple Tentacle trying to shrink your characters, and even then it is quickly

understood that it is more a matter of calmly and properly timing your

actions rather than action-style reflexes. All in all, cracking these puzzles

is a fun thing to do — and if you feel lost every once in a while, you might

as well just enjoy being lost, soaking in the game’s overall atmosphere while

waiting for a stroke of inspiration. |

||||

|

As inventive and ingenious as the

game’s many challenges are, let me tell you this: unless you yourself are

made out of silicon or any other semiconductor, you are not playing Day Of The

Tentacle to solve puzzles. You are playing Day Of The Tentacle to soak in its seemingly endless humor, whose

expanse in this game is at least several times wider than in Monkey Island — with the player

controlling three totally different characters for the price of one Guybrush,

and guiding them through three different worlds, with an atmosphere of total

whackiness being the sole tube of glue joining them together. It is still a pretty large tube of

glue, resulting in what I would call the only major weakness of the game’s

spirit: despite lots and lots of formally different elements that separate

the Past, Present, and Future (most notably visible in the graphic

representations of the respectively «colonial», «modern», and «futuristic»

models of the same mansion), all three settings still unfurl as rather

insignificant variations on the same panorama of absurdist characters. This

is at least partially intentional, given that some of the characters in

different epochs have their doppelgängers

in other time periods: for instance, the 18th century Benjamin Franklin,

flying his electricity-attracting kites on the lawn, becomes the

stereotypical 20th century novelty goods salesman with his gun lighters and

exploding cigars (if you were looking for a philosophical edge to this game,

here’s a good spot to stop and think). But the downside is that, while

switching from Hoagie to Laverne and back again, you are probably not going

to go «wow, now I’m in 18th century

America! and wow, now I’m deep in

the future!» Because essentially, you are just staying on different screens

of the same comedy world. Arguably the most fantastic thing about

the game are the characters of Hoagie and Laverne themselves. Unlike the

classic time-travel or Alice-in-Wonderland type setting, neither of the two

shows the least bit of confusion, giddiness, or amazed disbelief — instead,

finding themselves actually physically present in their new temporal

surroundings, they largely continue to behave the same way they would react

to just reading books on the subject, the only difference being the ability

to get some direct feedback from the info source itself. Hoagie’s type is well established by an

early dialog between Dr. Fred and Bernard ("Good boy. Does he have any

experience with electronics?" – "Uh... I once saw him take 3000

volts directly through his head without batting an eye" – "Didn’t

he pass out?" – "Well, he was already passed out when it

happened"). He may seem to be taken out directly of some early Nineties’

teen comedy, but the dialog he is given reveals him to be quite sharp and

inventive when he feels himself triggered — which, admittedly, does not

happen too often. His interactions with quasi-18th century Founding Fathers

are hilarious because neither of the two parties seems to pay much

significance to the decidedly odd looks of the other, though Hoagie does not

mind tweaking a bit of history to make it more adaptable to his modern tastes

(hence his endless stream of recommendations for the American flag to Betsy

Ross: "How about a skull with scorpions in its mouth?", "We

need a babe in a leather bikini, swinging a broadaxe", "The guys

say they want a big family crest, and in the four corners, they need a keg,

some babes, a guitar, and some drum sticks, and underneath it all put AMERICA

ROCKS!!"); clearly, his actual interest in his country’s history goes a

bit deeper than he allows to let on. In the end, Hoagie may be a

caricaturesque representation of the damn-it-all-to-hell mindset of the

astute, but lazy, rebellious, but nonchalant American teen from the early

1990s, but then the game’s Founding Fathers are equally caricaturesque — and,

in some ways, extremely

sacrilegious — depictions of the American Ideal as putting personal profit,

vanity, and pomp before everything else ("Does Mrs. Washington know you

wear so much makeup?" – "One must wear makeup when one receives the

phenomenal amount of media attention that I do", Mr.

Soon-To-Be-President humbly remarks). Unlike Sierra’s Pepper’s Adventures In Time, an «edutainment» project which was,

coincidentally, also released in 1993 and which actually tried to give the

players some sort of history

lesson, Day Of The Tentacle is more

concerned about, perhaps, giving you a hint that there may be far more in

common between the immaculately memorialized Founding Fathers and the lazy,

dirty, scruffy, value-less, nihilistic kids of today than one would suspect. But my favorite character by far —

arguably, one of the top 2–3 playable female characters ever written in the

history of video games — is Laverne. Nobody truly knows why she looks, walks,

talks, and acts the way she does — is it drugs? cerebral palsy? too much

formaldehyde in her medical lab? Officially, she qualifies for the status of

«strong female character», particularly seeing that she is chosen to survive

in the most dangerous environment of the game (the dystopian future in which

humans have been enslaved by Tentacles), but that strength is truly one of a

kind; throughout her segment, Laverne remains a mystery, and although we do

get that she is smart, on the whole her morals feel weirdly skewed, as she

allows herself to flirt with the tentacles and seems upset when the Tentacle

Doctor refuses to operate on her ("Are you gonna use your scalpel?"

– "No" – "Darn. Do you wanna use mine?"). The ambiguity

is all-pervasive: on one hand, she does warn us about the risks of putting

hamsters in microwave ovens, as if apologizing for the wanton cruelty of Maniac Mansion, on the other,

Laverne’s very first lines in the game, upon seeing the little animal, are

"Look, Hoagie, it’s a hamster... just what I need for the dissection lab

tomorrow!"). Despite the fact that modern players,

upon coming across Laverne’s character, tend to use (or even abuse) the word

"creepy" (indeed, I have a hard time imagining somebody writing a

character like Laverne into any video game released after, say, 2010), it is

precisely her "creepiness" that allows her to thrive and come out

on top in the Tentacle Dystopia, where she watches humans suffer their fate

with more scientific interest and, perhaps, even curious excitement rather

than such boringly predictable reactions as horror or pity. Humorous takes on

futuristic dystopia were nothing new in comics or cartoons by 1993, of

course, but I am not sure if any of those had such colorfully written

characters as Laverne to act as witnesses of the human race paying for its

pride and stupidity. Whenever I play as Laverne, I somehow get a vague, but

awesome feel of total invincibility coming over myself — verily the freaks

shall inherit the tentacle-ridden Earth, I say unto you. Beautifully and hilariously written

dialog is so abundant in the game that, had it been adapted into a movie, it

would have become an endless source of quotations to rival at least Monty Python, if not the more popular

and mainstream giants like Tarantino. "If you want to save the world,

you gotta push a few old ladies down the stairs". "What was your

favorite part of the Declaration of Independence?" – "I like those

S’s that look like F’s...". "Hello, my silent gauze-wrapped

friend... do you think it’s strange, me talking to a mummy? It’s not so

different from talking to guys at med school... except even you dress better

than they do". I could go on like that for hours, but I think you get

the drift even if you haven’t played the game (or were an utter fool and

rushed through it way too quickly, because a lot of that golden content is totally optional). It might, in fact, be the first

computer game ever whose atmosphere is created 90% by character interaction:

not fighting monsters, not running away from ghosts and ghouls, not wandering

around in beautiful and mysterious forests, not flying around in outer space

(the Chron-o-Johns would look decidedly silly in such an environment), not

going after pixelated romance, not enjoying the illusionary wonders of 3D

physics, but simply bumping one sprite against another and absorbing the

absurdist juiciness of the aftermath. And if you needed any additional proof

of that, there are a couple of objects, like the Textbook and the Invisible

Ink, which can be used on any NPC

in the game, past, present, or future, just to elicit a variety of responses

from the targeted crowds. (If you have Laverne taken out for a walk by the

Tentacle Guard and use the Ink on the monster, his response is "ON THE

GRASS! DO IT ON THE GRASS!", which always cracks me up). In doing so, Day Of The Tentacle really made your

machine come alive — although, of course, in order to achieve the required

goal, the game also had to make good use of technical progress, and this is a

good pretext to stop ranting on matters of substance and raise a glass to the

techie guys. |

||||

|

Technical features Note: The following section will cover (and, where

necessary, compare) both the original 1990 edition of the game and the 2016

Remastered Edition. No separate review for the remake is necessary, since it

changes nothing in the base game but rather just provides a complete overhaul

of its visuals, sound, and gameplay interface. |

||||

|

In terms of visuals, Day Of The Tentacle marked a

significant stylistic departure for LucasArts games. Peter Chan, who had

previously worked in a subordinate function on the art of Monkey Island 2, was assigned the

leading role, and his vision for the game demanded that it be made more

explicitly cartoonish and grotesque, Loony

Tunes-style. This approach did not quite stick with the studio — it

certainly influenced the style of such games as Sam & Max Hit The Road (released the same year and also

artistically directed by Chan) and Curse

Of Monkey Island, but overall, Day

Of The Tentacle probably remains the one LucasArts game that is closest

in style to a classic old-fashioned cartoon — something that was fairly

innovative back in 1993, when videogames were generally more busy thinking

about how to make their imagery more

rather than less realistic. The difference is

particularly obvious if you survey the transformation that the Edison Mansion

has undergone since the days of Maniac

Mansion. In the old game, although severely limited by lo-res EGA

graphics, the Mansion itself looked «normal» — at least, in that it had

normal walls, normal doors, normal beds, normal tables, next to which one

could find all sorts of weird objects and characters. The renovated Mansion

is all bent, curved, and twisted, with the main shapes and features remaining

largely unchanged all the way from colonial times into the future. So are the

characters, each of them drawn as a cartoonish type — Bernard with his 50/50

head to body proportions, Buddy Holly glasses, and obligatory bowtie; Hoagie

with his baseball cap, huge wads of eye-covering hair, pot belly, and

skull-adorned shirt; and, of course, our Supergirl Laverne, with naturally

explosive hair making all perms run for cover, clothes that ignore the very

existence of the word «fashion», and one eye twice as large as the other.

Animation of the leading sprites closely follows their basic shapes — Bernard

is always limp and slithery as a snake, Hoagie waddles like a tank (though,

when necessary, he displays an unusually uncanny ability to squeeze his huge

body through tiny holes), and Laverne... well, suffice it to say that she is

certainly in line to inherit John Cleese’s position at the Ministry of Silly

Walks. Nobody is spared the

ignominy, least of all the Founding Fathers who, admittedly, bear fairly

little resemblance to their historical prototypes, but are at least

recognizable by the... umm... shapes of their wigs? The important thing is

that the graphic representation matches the personality — poor John Hancock

has a permanently terrified and beaten up expression on his face, while

Jefferson, on the other hand, holds aloof with a look of absolute smugness

and haughtiness, and George Washington is just dandying around (he actually

looks about twenty years younger here than he really was at the time, so I’m

guessing Chan must have been a secret admirer, despite the strictest

directives to picture the Founding Fathers as anything other than

narcissistic fops). Similarly, the fascist /

dystopian elements of the game are also neutralized by the visual style:

Purple Tentacle and his minions are portrayed as not in the least

frightening, clownish buffoons jumping around on suction cups, with their

evolutionary victory achieved not so much through a diligent quest for

self-improvement as by the humans’ own unbeatable propensity for

self-destruction. If there is a single mildly

terrifying graphical presence in the game, it comes in the shape of the IRS

agents coming for an audit in Dr. Fred’s mansion, though, admittedly, most of

the terror comes from their carefully emotion-stripped voices than their

identical identities. The game features very few

close-ups or cut scenes, but in this particular case, it does not really need

them: the cartoonish characters manage to be pretty expressive even as

mid-size sprites, and there are no significant stylistic differences on those

rare occasions when Chan and his team zoom in on the little guys (one could

argue, for instance, that the close-ups in Secret Of Monkey Island looked stylistically jarring next to the

general look of the game). The cartoon style also works wonders on facial

animations during talking; although the animations are still largely

restricted to the mouth (sometimes the characters bob their heads, too), they

are more detailed, and come across as more «cartoonishly realistic» than

facial animations for more traditional digital sprites (e.g. Guybrush

Threepwood from the Monkey Island

games, or just about any Sierra game at the time). All this means that when it

finally came to remaking the game for modern graphic systems, more than 20

years later, it was decided that the original graphics — unlike those in the

first two Monkey Island games —

would only receive a proper facelift, instead of being completely redrawn

from scratch. Indeed, once the remaster finally appeared on the market, with

all the graphics upscaled and shiny and de-pixelated, it became clear that

this was the right approach. Just like a carefully remastered movie from the

old days, Day Of The Tentacle

Remastered looks 100% true to its original artistic vision, except that

it is actually possible to gaze upon it on a modern monitor without shedding

tears of disappointment — replacing them with tears of joy. If the new

graphic styles of the first two Monkey

Island games can have their supporters and detractors, it is hard for me

to imagine even the most hardcore nostalgia-phile complaining about the

game’s new look. (Other than, perhaps, the re-designed interface — but even

if one prefers the old mechanics, from a purely visual point of view the game

still wins, since the new pop-up interface allows the game picture to

completely fill up the screen). |

||||

|

Music for the game was

created by resident LucasArts composers — Clint Bajakian, Michael Land, and

Peter McConnell (legend says that each of the three was primarily responsible

for one of the three time periods: Bajakian for the 18th century, McConnell

for the 20th, Land for the 22nd). As usual, the soundtrack is never ambitious

enough to steal the spotlight, but it contributes heavily to the atmosphere,

with the music enveloping you every step of the way and the iMUSE system of LucasArts

ensuring for smooth transitions between the various parts of the soundtrack —

particularly important now that the player has the option of randomly switching

between three different characters (and thus, three time periods) at any

point in the game. As you can probably guess, Bajakian’s

18th century soundtrack is significantly different from the other two: little

baroque themes accompany Hoagie on most of his travels, except for his

presence in the Constitutional Hall, where a louder and prouder martial theme

replaces the more courteous music of elsewhere. The other two parts are more

similar, especially since Land’s «futuristic» soundtrack is created by relying

more heavily on electronic tones while often playing fairly conventional

vaudeville tunes for comic effect (apparently, musical tastes of the

Tentacles had been formed some time around the Jazz Age, if you can believe

it). That said, the soundtrack being nice

and all, it is clearly not the music that Day

Of The Tentacle will be remembered by, but the fact of it being one of the

first ever fully voiced LucasArts games (the very first, I think, was Indiana Jones And The Fate Of Atlantis)

— and not simply voiced, but voiced by professional voice actors, prepared to

give it their all. Voice director Tamlynn Barra (who had also worked on Indiana Jones) has to be given credit for

making all the right choices and giving all the right coaching, the result

being sheer comedy gold where pretty much every actor nailed pretty much

every personality. This inevitably means that my own

silver prize goes to Denny Delk for his deep, thick, ever-unperturbed,

mock-Zen impersonation of Hoagie (Denny would become an absolute LucasArts

veteran, starring in almost every game; arguably his most classic performance

is that of voicing Murray the Evil Skull in latter-day Monkey Island games) — and the gold, of course, goes to Jane

Jacobs as the bug-eyed, creepily somnambulant Laverne. Jane, unfortunately,

would soon afterwards forever disappear from the acting radar — but not

before giving Laverne that fit of terrifying evil laughter which you can

encounter from her at the most unpredictable of times, making you feel glad

that she and her scalpel, after all, are over there and you, the fortunate player, are over here. She also seems to have somehow

intuitively designed her own unique set of emotional expressions — her

Laverne is not actually bereft of emotionality, as she is quite capable of

expressing amazement, excitement, sadness, and anger (not fear, though: that

particular part of our girl’s brain seems to have been amputated), but her

semi-retarded, semi-philosophical way of processing all these takes some

getting used to. If we really feel the need to nitpick,

a small problem is that the studio’s budget was seemingly limited to only a

few actors, so that too many characters are voiced by the same person, and

every once in a while they might feel a bit overworked. For instance, David

"Mr. Zed" Traylor does a fantastic Ed Edison (the son of Dr. Fred,

recovering from the horrible trauma of his microwaved hamster), and a properly unpleasant Thomas

Jefferson, but his Ben Franklin comes across more like a fussy old Victorian

lady than (even a parody on) an 18th century American intellectual. And

Delk’s Hoagie is much more convincing than Delk’s George Washington, who

doesn’t exactly sound authentically «Virginian-English» (of course, nobody really knows what the general sounded

like, but I think a little more historic authenticity would have sounded

fantastic when combined with "I was just admiring my reflection in the

window... striking, aren’t I?"). That said, the absurdist-comedic nature

of the game easily absolves the actors from all such sins — after all, they

are not here to give you a lesson in American history, they are here to

subvert it and, if possible, send up the grotesquerie of its mythologization. |

||||

|

Interface The basic mechanics of the gameplay was

arguably the only aspect where the original Day Of The Tentacle did not introduce any innovations —

essentially, it runs on the same version of the SCUMM engine as several

previous LucasArts games, starting with Monkey

Island 2: the bottom left part of the screen is given over to nine

command verbs which you combine with objects, while the bottom right part

displays your inventory (represented by pictures rather than verbal

descriptors). The only addition is a special character icon, which you can

change to another character if you want to switch from Bernard to Hoagie or

Laverne. All of this has, however, been

redesigned in the Remastered

version of the game, where changes to the interface system are the second

biggest modification after the upscaled graphics. As in the Monkey Island remakes, the

screen-bottom interfaced has been completely removed — the inventory window

can now be brought up as a separate pop-up with a keyboard or controller

shortcut, and other shortcuts allow you to switch between characters.

Meanwhile, operations with objects or people are performed simply by clicking

on them and selecting one of several possible actions represented by pop-up

icons (LOOK, OPEN, CLOSE, USE, etc.). I think that the primary purpose for

this re-design was to avoid the issue of too many useless choices, as in the

original game, technically you could, e.g., TALK to the OUTHOUSE or OPEN

GEORGE WASHINGTON, which typically gave you just a generic negative answer.

The new system means more work for the designers (since each object in the game

has to be manually correlated with a specific set of actions), but less

unnecessary fuss for players, making the game a little easier to beat, as you

no longer find yourself flooded with tons of extra useless choices. Interaction with other characters takes

place largely in the form of dialog, for the options of which you get some

space freed in the bottom of the screen. The way dialog is structured, by the

way, constitutes another minor nitpick from me: a huge part of the game’s

charm is simply to engage your contacts in small talk, and much of that small

talk comes in the form of mutually exclusive options — as much as you want to

ask all the questions and retort

with all possible reactions, you

cannot (unless you abuse the hell out of your save and restore buttons). This

is actually typical of contemporary LucasArts games, which liked much more

than Sierra to give you the illusion of free choice, but is a bit frustrating

for a game which essentially does not need multiple playthroughs. (Note that

the guys at LucasArts eventually realised the problem — starting around The Curse Of Monkey Island, you were given far more free rein in

exhausting those dialog options). On the other hand, this does give you

the option to «build your own Bernard / Hoagie / Laverne» if you wish — a bit

more mean, a bit more sympathetic, a bit more curious, a bit more

indifferent, whichever you think suits the game’s atmosphere best. When

chastised by the Tentacles for her appearance, for instance, I always go with

"I guess I’d better go shoot myself, then", but you might want to

choose "Where I come from, I happen to be quite the babe" or

"I think I’m going to kill you" if you feel your Laverne feels more

like it. As I have already mentioned (and this

is a commonplace for LucasArts), the game mechanics completely excludes death

situations or lock-ups: useful objects do not expire until they have really

run out of use, your heroes are always free to trade stuff across the

chronostream, and if you fail at some task (like, for instance, getting the

Tentacle Judges to judge your entry in the Best Hair, Best Smile, Best Laugh

contest), you can always come back and try it again after making some

changes. But do not expect the Remastered

edition to make life significantly easier for you: other than including a

separate Developer’s Comment, there are no thrown-in hints to be had — so

either brace yourself for the challenge, or use your trusty Chron-o-John to

look up a walkthrough on the Web. |

||||

|

Day Of The Tentacle is

a game that will not be appreciated by «just about anyone», much like Monty Python or the Simpsons or Catch-22 or just about any work of art

built around a specific, idiosyncratic sense of humor — great comedy, maybe

even more than great tragedy, tends to be limited to certain wavelengths

which some people catch easily and some do not catch at all. And with

adventure games long since relegated to the dusty back shelves of

videogaming, you do not see it all that often listed in those predictable

«best games of all time» lists which typically begin with Mario Bros. and end with God Of War or something. But taken on

its own, outside of its humiliating historical context and genre limitations,

Day Of The Tentacle is as close to

perfection as a comedy-oriented adventure game could ever get (and the fact

that it came out in the same year as Gabriel

Knight, as close to perfection as a tragedy-oriented adventure could ever

get, clearly makes 1993 the single greatest year in adventure game history).

The brilliant premise of the plotline; the complex and absurd, yet oddly

logical puzzles; the uniquely unforgettable characters; the tasteful and

intelligent quality of the humor — the game succeeds at practically each goal

it sets before itself. In the end, one could argue, there is even a sort of general moral to

the game — illustrated by the brilliant final shot, as the Tentacle Flag is

hoisted up on the Mansion instead of the old Stars’n’Stripes (right after Bernard’s

closing words: "Looks like everything’s back to normal!"). If you

do so desire, the game can be

rationalized as a general warning for humankind, well on its way out due to

greed, vanity, and stupidity as illustrated by many of its characters. Yet that

motif in itself is nearly as old as humankind itself, and what matters, of

course, is not the message but the way it is delivered. And in the end, both

the message and its mechanisms of delivery feel just as relevant and poignant

today as they did back in 1993 — even if the game itself, as I have already

indicated, could only have been

done around 1993. So, if ever you needed an argument that old video games are

worth playing in the first place, go no further than Day Of The Tentacle to clinch it and crunch it. And put in

flying-V guitars instead of stars, for that matter. |

||||