|

The Elder Scrolls: Arena |

|

|||

|

Studio: |

Bethesda

Softworks |

|||

|

Designer(s): |

Vijay

Lakshman; Ted Peterson |

|||

|

Part of series: |

The

Elder Scrolls |

|||

|

Release: |

March 25, 1994 |

|||

|

Main credits: |

Programmers: Julian Lefay, Jennifer Pratt, Foroozan Soltani Artists: Bryan

Bossart, Kenneth Lee Mayfield, Jeff Perryman Music: Eric

Heberling |

|||

|

Useful links: |

Complete

playthrough, parts 1-13 (13 hours

5 mins.) |

|||

|

Just to impress

everybody about how much not of an

RPG-obsessed person I am, I should probably start this review with a stunning

disclaimer that, as of the exact moment of its writing, The Elder Scrolls: Arena is the only game in the entire Elder

Scrolls series that I have had the time to actually beat. I am familiar with all the other major

titles in the series, all the way to Skyrim,

but I still have a long road to travel here, and, as usual, I prefer to

tackle that road in proper chronological order, which is a good way to let

you look past the inevitable technological limitations of the old titles and

assess them not from a «retro-historical» point of view, but from a «time

machine» point of view, sort of reliving life from one stage back in time to

another stage forward. When Arena

was released, back in 1994, I had no chance whatsoever of playing it, for

various reasons (one of them being that my PC probably couldn’t have handled

the stress); but playing Arena before getting properly spoiled by the

likes of Skyrim is precisely the

way, I think, to be able to more properly appreciate both Arena and Skyrim, as well as

everything that came in between. Of the two big B’s in

the world of CRPG, Bethesda and BioWare (there’s also Blizzard as the third

one, but its primary focus is more on strategy and action than RPG), I am

naturally more partial to BioWare, whose goals — at least, while the studio

was in its prime — were always to combine an outstanding storyline, populated

with memorable characters, with elements of role-playing; The Elder Scrolls have always

prioritized role-playing over story, giving the player much more freedom of

action at the expense of making these actions feel like they really, really

matter. However, as far as tools for the «build-up-your-own-story»

construction kit are concerned, few, if any, competitors have matched the

ambitions of Bethesda over the years — and as The Elder Scrolls: Arena amply shows, these ambitions were there

right from the very start. Pretty much every game in the series always tries

to bite off far more than it can chew — and pretty much every one fails, to

some degree or other — but the failures themselves still manage to be

fascinating, and their sins forgivable. Unlike BioWare, a

company that pretty much started out with its dream transparently laid out on

paper and went from nothing to stardom upon releasing its second game (Baldur’s Gate), Bethesda Softworks

seem to have waddled into the RPG market almost by accident. For eight years

since its incorporation in 1986 by Christopher Weaver, it was putting out a

rather motley assortment of sports simulators, shooters, and rather

lackluster action-adventure titles like the Terminator franchise; it is probably safe to say that few of

those provide even purely historical interest at present time (I’ve not

played any of them myself, but watching the old game footage on YouTube has

not been particularly arousing). However, sometime around 1992–1993 the stars

aligned rather happily for the company, putting together three talented

people — designer / producer Vijay Lakshman, senior designer Ted Peterson,

and programmer / engineer (also occasional composer) Julian LeFay. (Cue voice of doom) It has been foretold in The Elder Scrolls...

that some day three heroes would cross paths in order to design a really cheesy

game about teams of warriors traveling through an epic world, fighting each

other in the various combat arenas scattered across the land until only the

strongest remained, or some crap like that. Fortunately, collective intellect

won over collective stupidity, and the raw game mechanism soon took on a life

of its own, with its creators wisely following their instincts and creating

something completely different from what was originally planned. Thus, although The Elder Scrolls: Arena still

happened to retain its original name, for whatever technical reasons forced

it to, there are no «arenas» in the game whatsoever — instead, having

(accidentally, I’d like to believe) discovered that all three of them were

fans of tabletop RPGs as well as already prolific CRPGs of the Ultima variety, Ted, Vijay, and

Julian simply decided to make nothing less than the hugest, grandest, most

ambitious RPG of all time. Perhaps if they’d already had a lot of experience

with the genre, they might have reined in their ambitions and settled upon

something of a smaller scale — but fortunately for history, they knew very

little, if anything, about how to make an RPG, which is a great starting

condition for a terrible, laughable embarrassment if you lack talent and

insight, or for something truly outstanding if you do not. And for all its

major flaws and all of its under-reached goals, The Elder Scrolls: Arena was

truly and verily outstanding. Even those who would

find the game tedious and unplayable today would still have to acknowledge

that it was quite a breakthrough in several important aspects. It implemented

the huge, near-infinite open world game mechanic like never before —

absolutely breathtaking in pure geographic scope (even if most of that scope

was rather illusive, as we shall find out eventually), it remains the

great-great-grandfather of the majority of today’s open-world RPGs. It was,

arguably, the first title to successfully and convincingly introduce

first-person perspective into RPGs (inspired in large part by Ultima Underworld, for sure, but

that game looks laughable next to Arena).

It placed a huge emphasis on atmospheric properties, utilizing sound and

visuals to trap the player in its virtual reality. It... well, let’s save all

those other things it did for the actual review. Unfortunately, it also

did most of these things somewhat crudely — or, to put it more politely, it

was somewhat ahead of its time with many of its ideas. In most of the veteran

gamers’ memories, I believe, the legend of Arena has been largely eclipsed by the memory of The Elder Scrolls: Daggerfall, the

follow-up title from 1996 which is commonly brought up as the proverbial Bethesda masterpiece

from the early days. I happen to actually prefer Arena myself, and I think it is largely due to the fact that I’ve

been late to the party by more than twenty years; today, Arena, as played through various DOS emulators on PC, no longer

feels as cumbersome and unwieldy as it must have felt to most PC owners back

in 1994, and to me, its sprawl feels a bit more balanced than that of Daggerfall. However, this is, of

course, a matter of opinion — both games have their own elements of

uniqueness, and ultimately it all depends on what you’re really here for. Back in its day, of

course, Arena had its fair moment of

glory, with Computer Gaming World

voting it the best RPG of 1994 and gamers worldwide amazed at its dashing

sprawl. Yet due, among other things, to the fact that it failed to properly

and definitively establish the lore of The Elder Scrolls — something that

would only happen with Daggerfall

two years later — Arena had the

misfortune to become sort of the «spiritual black sheep» of the series, an

early take that feels disconnected from the fantasy universe of Tamriel built

up in the later titles. For that reason, present day devotees of the Elder

Scrolls saga are often found scoffing at the game, inciting novices to start

their journeys with Daggerfall (if

they want a particularly harsh «old school» challenge) or any of the ensuing

games from Morrowind to Skyrim. But I think that even if Arena happens to be totally

excommunicated from the Church of The Elder Scrolls, it still has quite a few

delights to offer on its own, as a stand-alone title. In fact, precisely

because of the fact that it spends a little too much time looking over its

shoulders at achievements of the past, always thinking about how to improve

on them, rather than on building up a grand new universe for the future

(which is the chief occupation of Daggerfall),

it ends up being more adequate and balanced in some aspects than its somewhat

chaotic follow-up hodge-podge of kaleidoscopic ideas. In the ensuing sections

of the review I’ll try to show more specifically what I mean — and yes, we’ll

have to resort to quite a bit of comparative analysis in the process. |

||||

|

Content evaluation |

||||

|

Most of the Elder Scrolls games are, to some extent, defined by how their

«main quest» is integrated (or not integrated) with the «side quests», and

the specialty of Arena is in that,

after a short while, it is only the «main quest» that remains worth following.

After creating your character, you start the game in a dungeon where you, the

last survivor of the loyal Imperial Guard, have been thrown by the evil mage

Jagar Tharn after he has staged a coup against the Emperor Uriel Septim VII,

imprisoning the poor guy in Oblivion and assuming his shape in order to rule

for his own sinister purposes. As you escape from the dungeon, guided by the

instructions of the friendly (but dead) sorceress Ria Silmane, your obligation

is to restore the Emperor to power and deal with Tharn — to do this, a

powerful magical artifact, split by Tharn into eight pieces, has to be found

and reassembled piece by piece; only after this can you actually storm the

Imperial Palace itself and confront the traitor face-to-face in a final

showdown. It is a simple and repetitive plot —

perhaps the simplest ever in an Elder

Scrolls game — yet, in a way, it is rather surprisingly effective.

Starting with Daggerfall, you

always run the risk of getting way too confused and mixed-up while sorting

out the endless mutual strifes and bickerings of the various factions, with

the big goals (if they can even be called big) getting diluted in an endless

sea of local problems. Of course, this is all perfectly normal for ambitious

CRPG settings, but sometimes there is something to be said about

straightforward simplicity, too, and Arena

is as simple as they come. Later games would be all twisted and zig-zaggy; Arena’s mechanism is straight as an

arrow. Each of the eight parts of your precious artifact (the Staff of Chaos)

is hidden in one of the eight provinces of Tamriel. By getting a first clue

from Ria and then asking around, your hero is directed to a location in one

of the cities, where some king, mage, or priest asks for an initial favor —

which always means clearing out a huge dungeon — to provide a map of the

location where the Staff piece is hidden, whereupon you go there and clear

out a second huge dungeon to get to

the piece in question. Then you get a dream vision of Jagar Tharn who gets

more and more mad at you, even sending in a couple of assassins that are

easily dispatched. Then rinse and repeat. Ultimately, this means having to

complete a whoppin’ sixteen huge dungeon crawls, two for each province,

before the final, eighteenth one (the first one is your escape from the

starting dungeon) where you shall have to confront your strongest enemies,

including Tharn himself. Although there are some tiny bits of lore associated

with each of these individually designed places (as opposed to procedurally

generated mini-dungeons scattered en

masse all over the continent), most of your time in them will be spent

finding your way around and fighting monsters rather than talking or

interacting in non-combat fashion. The good news is that most of these places

have their own personalities — ruined castles, abandoned mines, ice-encrusted

strongholds, mist-filled gardens, lava-choked volcanic craters — and although

the designers’ fantasy eventually begins to run out toward the end, as a

rule, scouting out each of these locations is its own experience, though it

certainly has to do more with «atmosphere» than «plot». The aforementioned tiny bits of lore

are, however, relatively worthless. The basic thing for us to understand is

that we simply have to go to the dungeon, kill everybody in our way, get the

required McGuffin and go forward. Paying serious — let alone emotional —

attention to your local ruler or wizard explaining why he or she needs the

item in question is not in the least obligatory to complete your assignment. Very occasionally, you might require

to collect bits of information in the dungeons you explore in order to answer

some of the riddles that the game’s locked doors sometimes ask of you; other

than that, there is hardly any «knowledge» you need to assemble in order to

facilitate your progress or feed your emotions. A couple of the crawls are

accompanied by your slowly unwrapping the details of some terrible

Shakespearian tragedy that had happened in the place in question (such as the

mini-story of the brothers Mogrus and Kanen inside the Labyrinthian), but

there is no actual involvement on your side in these stories, and with

minimal text and no voicing going on, their artistic value is non-existent:

really, they’re only there to make the crawls a touch less monotonous. Things are even worse with the side

quests, most of which are randomly generated from pre-written blocks — these

usually involve rescuing some damsel or noble’s son from a dungeon, accompanying

somebody somewhere, capturing a criminal, or, on a rare occasion, hunting

down a unique artifact that will help tremendously boost some of your stats.

None of these quests, which you typically get from hanging around with

innkeepers or nobles wherever you come to visit, have any relation to the

«main quest» or, in fact, can even be considered as a minor part of the

«plot»; they are simply there to provide extra content, extra opportunities

to get extra loot and cash, buff up your character, and help you catch a

breath in between the major dungeon crawls. I would typically find myself

getting a small bunch of these early on in the game, then forget about them

altogether — because you can really level up all the way you want while

simply doing the main quest. (And those tiny four-level dungeons generated

for side quests are usually very, very generic and boring anyway). Still, in a sprawling RPG game like Arena there is something to be said

about minimalism, I guess — and although the final encounter with Jagar Tharn

is rather short and disappointing (he does not even get his own unique

sprite, and by the time you meet him face-to-face, you’ll probably be leveled

and buffed up to such a point that you’ll take him out in a jiffy), the way

he keeps pestering and taunting you through each of your achievements does

feel epic. At least there is a very clear goal and a very clear — and

cleverly increasing in difficulty — path that leads to it in a very classic

mythological, labour-of-Hercules sort of way. And while subsequent games

would strive to make your living in Tamriel being a bit more on the mundane,

realistic side, this is precisely what makes Arena stand out — a bit of an epic, poetic feel to it which would

already in Daggerfall be replaced

by a far more pragmatic and even cynical approach to all that hero business.

It’s a bit like pitting The Iliad

against A Song Of Ice And Fire, if

you catch my drift here. There’s probably a place in our life for a little of

both. |

||||

|

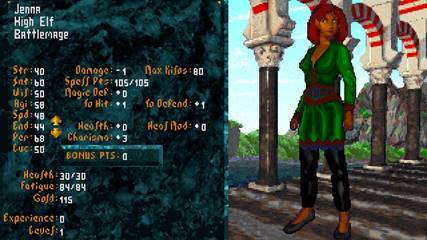

Compared to how Arena looked and felt upon release, the things you

could and would do within Arena must have seemed somewhat

underwhelming. Essentially, Arena

does what any generic RPG expects you to do. You start off with «rolling» a

character (most people usually keep on re-rolling until the initial stats

look impressive enough) — prior to which you may or may not wish to have the

game assist you in choosing your class by testing you through a series of

easy-to-see-through questions (e.g. "your

neighbor stole your watch, do you (a) beat the shit out of him?, (b)

hypnotize him to make him return it, (c) rob him blind in the middle of the

night for revenge?"). Then you tweak your typical RPG stats

(Strength, Intelligence, Agility, Luck, etc.) a little, and off you go to an

existence that shall largely consist of three constituents: Communication,

Commerce, and Combat. Beating the game is much more about grinding in all

these three areas than anything else. Simply put, to learn the locations of

the artifacts you’re supposed to collect you have to travel around — usually

at random — and ask the various people you meet on your journeys. They don’t

have a lot to talk about — sometimes they can deliver you a random, and

usually meaningless, piece of news for sheer virtual pleasure, or point you to

a place where you can find a generic side quest to complete; but sometimes,

completely at random, they do give out a valuable piece of information. Thus,

all that’s needed here is patience. Once you have finally been pointed in the

right direction, before invading one of the «macro-dungeons», you need to

stock up on decent weapons and protective equipment (everything from armor to

magic potions); this is done at local stores, all of which look alike, where

you’ll probably do a lot of bartering at first, that is, before you become so

overloaded with money that bargaining becomes merely a time-consuming chore.

(I usually end up buying a shitload of health and other potions, which saves

you quite a lot of time in the dungeons). Finally, there are the dungeon crawls,

which will probably occupy about 85-90% of your entire playing time — and

it’s a good thing, because Arena is really all about

dungeon-crawling. The smaller dungeons, procedurally generated for the sake

of minor side quests, are not very interesting — they usually consist of

about four levels each, with a small number of random enemies scattered

around differently configured corridors and chambers, and once you’ve

explored a couple of those, I don’t see how it could be particularly

interesting or fun to waste time on even more. The large, hand-crafted dungeons, are an entirely different matter

altogether — not only do they have interesting bits of unique design, but

they typically offer an extra level of challenge, where you have to guess

riddles to open locked doors, find your ways around deep pits and lava pools,

locate hidden keys on bodies of occasional mini-bosses, and regularly meet

new, stronger types of enemies as the older types grow weaker and weaker

while you level up. Combat itself, like in most classic,

pre-action-adventure day RPGs, is not difficult, and its results usually have

more to do with the current level of your character, as well as the luck of

your dice rolls, than with true player agency. Incidentally, Arena was the first, or at least one

of the first, games to introduce mouse-based combat into PC RPGs, but this

just means that you have to constantly move your mouse back and forth while

slashing at the enemy, requiring no special player agility at all; the

results of your slashing will always be determined by your and your

opponent’s respective levels — and quite a bit of luck, nothing else. Thus,

(a) leveling up is really important, (b) packing stuff is really important,

(c) understanding when to fight and when to run like crazy is really

important. That’s about as much intelligence as it takes to beat Arena to its conclusion. Now, of course, if you want to, you can get pretty creative,

particularly if you are a magic user — like quite a few RPGs, Arena makes the mistake of being

obviously rigged in favor of the wizard class. Thieves may be extra sneaky

and fighters may be extra tough, but living your Arena life as a thief or a fighter ultimately becomes quite

boring, whereas wizards have the advantage of constantly learning new, more

complex and exciting (and expensive, not to mention mana-costly) spells — in

fact, Arena boasts the presence of

its own spell-constructing kit, where you can waste hours of your life

designing the most bizarre spells in the world. Want to have a spell that

launches a fireball at your opponent, while also poisoning him at the same

time, making you invisible and

sending you off to levitate in the air? Yes you can, provided you got the

money and you got the spell points required for casting the little wonder.

Easily the single most challenging and brain-wrecking task in the entire game

is to come up with your own ultimate doomsday spell that shall make even the

most dreadful boss creature disintegrate before your eyes in less than a

second... ...the only problem here being that all

these things are essentially not

required, they’re all here for the sake of entertainment only. The regular

spells that you can buy at the various Mages’ Guilds cover all of your needs

perfectly just as they are, and the practical use of a complex spell that

makes you invisible, cures you of poison, and destroys your enemy at the same

time is pretty dubious in the first place — usually, you’d want to do those

things separately rather than all together. It would actually be nice if,

every once in a while, the game would force

a magician to use the Spell Construction Kit — just to emphasize its

importance for boss battles, for instance — but it never does. Consequently,

having fooled around with the system for a short while, I quickly grew bored

and disenchanted with it, sticking to regular spells from then on. In the end, player qualities that Arena rewards the most are patience, obstinacy, and (optionally) calculation,

which, of course, is hardly surprising for any CRPG veteran. Building up and

properly equipping your character, accurately mapping out the huge, twisted

dungeons, diligently saving all over the place after making another small bit

of progression — all of these things demand far more of your time than they do of your intelligence. Hence the obvious

question: with so simple a plot, and such trivial a path of action, is there

truly anything in Arena that could

be worth your time? |

||||

|

Indeed, if there still remains one

reason for people to continue bothering with Arena, it is simply the fact that it has a fairly unique «aura»

to it. Perhaps the best way to feel it out is to compare the dungeons of Arena with what must have been its

chief inspiration — Ultima Underworld,

released two years earlier. While I have not played it myself, watching bits

of gameplay on

YouTube clearly shows just how much Bethesda specifically pilfered from its scrolling

3D landscapes. There is the same first-person perspective; the same endless

labyrinth of stone corridors, walls and doors arranged in chaotic and

befuddling manners; the same limited field of vision, with new walls and

corridors — as well as unexpected enemies — rising to meet you out of the

darkness, with creepy music following you around and occasional juicy pieces

of loot strewn on the ground. However, the two years elapsed between 1992 and

1994 proved to be rather crucial: while Ultima

Underworld’s dungeons, at best, might look «fun to navigate» to some

people, Arena’s dungeons continue

to feel creepy as hell, easily just as unnerving when you return to them in

the 2020s as they were back in the era when they represented the ultimate

pinnacle of digital technology. Much of this has to do with the game’s

handling of sound, arguably the

game’s highest technical achievement and one of the finest examples of

atmospheric audio in any game I have ever played, period (yes, it compares quite masterfully even to modern titles

in that respect). But this is not the only component of the game’s

atmosphere, far from it. On the whole, Arena

succeeds in building up a bizarre, but believable alternate reality in which

the principal, if not the only,

goal is to survive, and in order to survive, you have to build yourself up as

diligently as possible. Formally and superficially, this is a common goal in

most RPGs, but not all of them flash it in your face as persistently as Arena does. Paradoxically, even if

its sequel, Daggerfall, would on

the whole be a much more difficult game, in which the balance between life

and death is very much skewed in

favor of death, Daggerfall, to me,

rarely feels as tense and unnerving as Arena. In their tales of their own struggles

with Arena, people frequently

complain about the difficulty curve and how it took them 15 or 50 tries to

even get their character out of the starting dungeon. This complaint usually

has more to do with not perfectly understanding how the game works — in

addition to a lot depending on the

luckiness of your initial rolls, you are pretty much supposed to take plenty

of damage from even minor enemies, such as Rats or Goblins, at the beginning

of the game, and use safe spots and niches to rest and recover. Once you got

that simple tactic down, Arena is

not particularly difficult, except when you run into one of its many bugs;

however, even after that it does not cease to be creepy. Honestly, there are fairly few games

out there in which the enemies would be as persistently nasty as they are in the Arena.

Typically, they creep up on you from somewhere ahead in the darkness, where

you can sometimes discern them from a little afar by the distinctive sounds

they make; however, they are just as liable to creep up on you from behind and stab you in the back when

you least expect it (usually, I think, it happens when you go past a closed

door without bothering to check what is behind it, and alert your presence to

the enemy — but sometimes it feels as if the game is simply scripted to have

fiends materialize from nowhere). As a rule, they are really ugly and really

persistent, their only purpose in life being to hunt you down for no reason

at all — malicious killing machines, yet endowed with their own

species-specific personalities. However, as you gradually level up, formerly

formidable enemies gradually become nuisances that you easily dispatch with a

couple blows or a couple well-placed spells — until, by the end of the game,

once you have accumulated enough XP, even the most dangerous challenges such

as Liches or Vampires go down before you like sacks of potatoes. At the beginning of the game, though, hoo boy, you’re in for some really

tough time. At least the opening dungeon is relatively small; but already

your very first serious mission — find a tiny piece of parchment in the huge

dilapidated castle of Stonekeep — can overwhelm you with its sheer scope and

deadliness. The designers lure you in with simple enemies at first (the same

rats and goblins that you have already become accustomed to in the starting

dungeon), then begin mockingly introducing you to speedy wolves, brutal orcs,

nearly unbreakable skeletons, paralysis-inducing spiders, and, finally,

club-wielding, disease-spouting Ghouls, defeating even one of which takes

pretty much all you’ve got... and there’s a whole pack guarding that blasted

parchment. Above all, it is the space

of the whole thing that shall take the wind out of your sails. Dining halls,

libraries, flooded dungeons, earthy basements, underground currents — by the

time you’re finished with your dungeon crawl, you’ll be literally sweating. And there is no «Recall» spell as

there would be in Daggerfall —

having made your way deep into the bowels of the dungeon, you’ll have to

crawl out of it as well, only praying on your way back that all those

innumerable enemies have not yet had time to respawn. As you gradually level up and become

more used to your enemies’ treacherous tactics, the atmospheric qualities of Arena are liable to begin inducing

boredom — even if, as I already said, the designers try to keep the main

quest dungeons as diverse as possible, there is only so much you can do with

a fixed set of starting blocks, and by the third or fourth piece of the

Staff, all those underground pits and lava rivers will no longer feel

particularly exciting. Still, there always remains a certain element of charm

in the meticulous exploration of all that hand-crafted dungeon space,

especially if you are endowed with the famous Passwall spell that allows you

to remove a piece of the dungeon wall if it seriously gets in your way or if

you’re too tired of endless backtracking from dead ends. Eventually, subtly,

the game morphs from «survival horror» to «cartographic lessons», which could

very well appeal to the obsessive elements of our nature — my main complaint

is that the cleared maps, which all look so nice and neat on the Map screen,

are wiped clean after you leave the dungeon; so if you want to return to one

of them for some reason, you’ll just have to start mapping them out all over

again. Outside of the dungeons, the atmosphere

is, of course, provided by the vast open spaces — endless plains strewn with

randomly generated roads, trees, rocks, farmlands, and an occasional

loot-filled, monster-populated mini-dungeon every once in a while. Added to

this is an expertly crafted day-and-night cycle and occasional weather

effects (e.g. snowfalls in the Northern provinces). Unfortunately, as it

usually gets with procedural generation, the vast world does not really come

alive all that much: there is nothing you can do with the immovable random

decorations, and you cannot even properly get by foot from one area to

another. Interaction with the locals scurrying around the towns and the

countryside is possible and at first even looks varied as they introduce

themselves to you, share pieces of local or general news, drop hints about

finding work and provide information on the city’s taverns, guilds, and

shops; pretty soon it becomes obvious, though, that all of that chatter is

procedurally generated just as well, and that not a single person you meet in

the streets or inside the building is actually a personality — not even the several «specially» named characters

(like «Queen Blubamka of Rihad»!) who have unique pieces of main

quest-related dialog (once they’ve exhausted those couple of paragraphs, they

simply revert to being a part of the same nameless crowd). Generally speaking, it is clear that

the creators of Arena were first

and foremost obsessed with size.

The big cities of Tamriel are truly big, each one containing dozens of

landmarks; the dungeons generated for the main quests take hours and hours to

properly map out; the distances between cities are infinite; and if, through

some crazy desire to set a really stupid Guinness record, you wanted to

visit, explore, and map out each city, town, village, and dungeon on the

continent, it could literally take you a lifetime of doing nothing else

(although Daggerfall, I believe,

would take that approach even further). For PCs back in 1994, the results

must have felt monumental, provided they were capable of running the game in

the first place; today, eyeballing this largely meaningless vastness is about

as exciting as settling down in your comfy chair and reading aloud the first

half a million sequences in a decoded strand of DNA. Yes, we know that space

is infinite but we also know that it is mostly empty — although, granted,

some people may get off on the idea

of vast empty space. To me, the most appealing point of Arena’s atmosphere is not the game’s

sheer size, but the very contrast between «safe» and «dangerous» space. The

best feeling? When you happen to arrive in some town late at night, with all

the shops and guilds closed and occasional monsters and bandits roaming the

streets. You’re looking for a place to stay, and there is nobody around to

give you directions, and suddenly some unknown enemy hits you in the back and

takes off a solid chunk of your health bar, and you have no idea if it’s a

measly Orc or an overpowered Wraith... and you run for your life, desperately

looking for signs of salvation, and then, finally, you see a heart-warming

tavern sign... you rush inside, still pursued by your unknown enemy, and

suddenly find yourself in the «comfort zone» — bright, warm, pleasant, with

merry music playing around, an opportunity to rest your bones, recover your

health, and check the local gossip. That

is the kind of thing Arena does

incredibly well, and even if it cannot properly bother to make any of its

NPCs come alive, at its best, it makes you

feel very much alive by staying on your toes in a world where pretty much

everything out there is out to get you, sooner or later. Strange as it seems, too much emphasis

on the plot might have probably ruined some of the game’s atmosphere, as it

ended up happening with Daggerfall,

a game which — I absolutely insist — is seriously less atmospheric than its predecessor, much more concerned with

giving the player more freedom of action and pseudo-diversity at the expense

of emotional reactions. I, therefore, do not mind all that much that we do

not get to properly bury ourselves in the court intrigues of the many rulers

of Tamriel, concentrating instead on killing as many monsters as possible to

get to that coveted next rank. |

||||

|

Technical features |

||||

|

While it is obvious that in

retrospect, the visuals of Arena

have no chance of remaining its strongest selling point, back in 1994

Bethesda’s achievements on this front must have felt quite spectacular. With

a native VGA resolution of 320x200, the game’s engineers still managed to get

it at least up to the level of Doom

— no mean feat for the time — and perhaps even improve on that level, as the

graphics of Arena strive for a bit

more realism and complexity. However, they also have to struggle with the

same issues as Doom, or just about

any 3D action or RPG game released at the time — most notably the «open

world» principle, under which the number of on-screen visuals available for

the player is technically supposed to be infinite, meaning that they are all

composed of pre-crafted «building blocks» that may be combined in an endless

variety of ways. As a rule, this principle does not really transform into

aesthetic beauty; the only thing that matters is the illusion of plunging the

players into an alternate reality, unconfined by the limits of their monitors. However, I would not be too

sure to insist that the graphics of Arena

are entirely subdued to purely

pragmatic purposes, as becomes obvious when you compare it to the likes of Ultima Underworld. First, adequate

care has been taken of the little details. The sprawling dungeons feature

wall decorations, rusty chains, dirty weeds, gnawed bones scattered across

the floors, etc. The cities, towns, and hamlets of Arena have lamp-posts, fountains, statues, nicely trimmed lawns,

etc. Probably the most disappointing places are interiors within townhouses —

as a rule, they just feature empty spaces, sometimes with tables and chairs

(there aren’t even any closets or beds, for that matter — whenever you go to

sleep in an inn, one wonders whether you’ve just had to spend the entire

night flattening your bones out against what looks like a primitive surgical

table) — but at least you’re not really supposed to be spending a lot of time

in there. Second, it would not be

right to deny a certain style to

all these building blocks. The dungeons, with their huge stone slabs, earthen

floors, and low-hanging ceilings, have a brutal, claustrophobic look that

sometimes actually makes you wonder about who and under which circumstances

could ever have populated their territory with such menacing structures. The

towns, most of which look very much alike apart from a few environmental

details here and there (e.g. palm trees in some regions vs. fir trees in

others, etc.), give off the probably intentional-and-desired effect of «human

anthills», where people scurry about their business just because such is the

law of nature. In some ways, the relative primitiveness of the graphics even

in comparison to Daggerfall only

accentuates the idea of the world being a dangerous and depressing place

(both the exteriors and the interiors in a typical Daggerfall town would look a tad nicer and cozier, suppressing

the overall feel of danger). Third, the 3D aspects of

Tamriel are handled reasonably well. Although the game’s draw distance is

laughable by modern standards (you can do something about it by fooling

around with the Details slider in

the settings, but not too much), having blurry faraway objects suddenly

transform into houses, statues, and people before your eyes is still

impressive — or jump-scary, whenever your advancing in a dungeon triggers the

emergence of some particularly nasty enemy from out of the shadows (one

reason I always go for a Light

spell early on in the game — somehow having your Vampires and Golems appear

out of a brightly lit nothing slightly reduces the chances of a heart attack

if you have them appear out of total darkness right under your nose). And the

scaling issues with NPC and enemy sprites are almost non-existent: they look

just as realistic up close as they do from several meters away (compare, for

instance, the really clumsy scaling

results with Sierra On-Line games released just a year or so earlier, when

small-size sprites would look awfully pixelated when moved to a virtually

«close-to-the-player» position). (Of course, we’re talking 1994 standards

here, not 2020.) Serious care was applied to

the enemy sprites, making most of the monsters truly antipathetic. The

multi-legged hissy spiders are all brown legs and feelers, ugly as roaches

and stretched out like Martian war machines (more intimidating than spiders

in Daggerfall, which kinda look

like puffed-up rubber toy models in comparison). The vomit-colored ghouls

look like walking puddles of infectious disease (which they are). The ghosts and wraiths actually look ghostly, with semi-transparent

pixelated bodies through which you can walk (if you are brave and sturdy

enough, that is). The Liches have rather uncharacteristic manes of red hair

flowing atop their skulls, which gives them a bit of a progressive rock-star

look on the whole — an original touch that actually makes this type of enemy

more memorable than the one in Daggerfall.

Unfortunately, this does not apply to the main antagonist (Jagar Tharn), who,

for some reason — perhaps they ran out of budget at the last minute — does

not even get a unique sprite to his name and is «disguised» as just a regular

Vampire, which always confuses players at the end of the game (and makes the

final boss confrontation quite underwhelming). On the other hand, Jagar

Tharn is one of the few game characters who gets an actual close-up (along

with Ria Silmane and the Emperor), so that’s at least worth something — and

speaking of close-ups, the game’s few attempts at actual hand-drawn art,

mostly represented by exterior depictions of the eight locations containing

the eight pieces of the Staff, are surprisingly vivid rather than purely

schematic. Too bad they couldn’t have more of them, to make at least some of

the game’s locations a bit more individualistic. |

||||

|

If there is one thing that Arena does better than most of the

early games in the Elder Scrolls

series, it is the audio part of the entertainment — I’d go as far as to say

that the game is more worth picking up to be heard than to be seen,

and that most of its atmosphere is conveyed by means of (a) its actual

musical soundtrack and (b) one of the most effective uses of sound effects in a video game I’ve ever

witnessed. The full CD-ROM edition of the game also has a third audio

component — voice acting — but it’s a really small one, even if it does

significantly contribute to the atmosphere as well. Let’s start with the soundtrack. It was

composed by relatively little known video game composer Eric Heberling, who

had already provided the General MIDI soundtrack to Bethesda’s proto-Doom-like Terminator: Rampage —

which is certainly OK as far as shooter-style rhythmic electronic soundtracks

are concerned, but predictably monotonous in its harsh, kill-’em-all aggressive

vibe. By contrast, even if the collective length of all the tracks written

for Arena barely exceeds 40

minutes, they feature an astonishing range of vibes and attitudes — and some

are even quite catchy at that! Considering that, as you stroll through

Tamriel’s towns and dungeons, this soundtrack has to accompany you for hours

on end, it is almost a miracle that I never

find myself wishing to turn down the music, despite its continuous loops. Heberling introduces a fairly strict

division between «safe space» and «dangerous place» music — the tracks played

at daytime in the towns and countryside, on one hand, or at nighttime and

inside the dungeons, on the other. For the first group, the main inspiration

probably comes from various strands of Renaissance music, though he obviously

applies the «ABBA filter» (take a classical piece and simplify it to the

point of being instantly memorable and accessible, that is) and makes full

use of MIDI synths as autonomous atmospheric entities rather than just

piss-poor emulations of real instruments. The result is some truly beautiful

soundscapes such as ‘The

First Seed’ (which typically plays on bright summer days inside and

outside the cities) and ‘Winter

In Hammerfell’ (playing, respectively, on wintery, snowfall days in the

same locations). There’s really nothing like getting enveloped in the «cute

solemnity» of the former or the «friendly frostiness» of the latter when you

need an antidote to the robotic randomness of Arena’s hustle-bustle going around — with the slightly

otherworldly feel of the MIDI tones (and I’m pretty sure it just wouldn’t work if played on real

instruments), the game is instantly elevated to a whole other level, making

it so much easier to suspend disbelief than through chatting with the

lifeless, AI-generated townspeople. The «dangerous» music is more on the

ambient level; thankfully, it never goes into full-on shooter-mode (after

all, you are not supposed to rush

through dungeons in Arena,

shooting up baddies with badass-looking carbines — it’s a slow and meticulous

affair here), preferring instead to concentrate on suspenseful, unnerving

tones; one possible complaint might be that there is no actual «combat music»

even when you actually run into an enemy, but since you run into enemies so

frequently, that might mean too many abrupt interruptions, so the decision to

keep the same low-key suspenseful ambience even when you start hacking away

at a pack of goblins is understood. In any case, the experience of sitting

through a couple hours of this creepy ambience and then finally escaping the

dungeon for the local tavern, where you are greeted by a cheerful bit of

Celtic dance, is an absolutely heartwarming one. As monumental as later era Elder Scrolls soundtracks would

become, naturally culminating with Skyrim,

there is an absolutely unique charm to Heberling’s creation here — and I am not saying this out of general

nostalgia (which I couldn’t experience even if I wanted to, having never

played Arena until the 2010s) or

out of some «early MIDI music is always cool!» puffed-up principle: I just

happen to recognize talent when I hear it, and I think that Heberling

actually made the world of Tamriel a more unique

place in nature than Jeremy Soule did with all the Elder Scrolls games later on (starting with Morrowind). The Arena

soundtrack is simpler, quieter, less pretentious, a little child-like in

places, and does a much better job of transporting you into a universe of

«naïve childish beauty (and/or terror)» than the later soundtracks for

games that were trying to advance from the level of pure make-believe to a

certain degree of «fantasy realism» (and, for that matter, failed more often

than succeeded in achieving that goal anyway). Another area in which the game truly

excels are the sound effects — although this applies exclusively to its

dungeon-crawl sections. Inside the dungeons of Arena, hearing is even

more important than seeing at

times: enemies typically announce their presence to you by making typical

sounds which you can hear from afar, coming from ahead in the corridors or

even from behind the walls (so sometimes it takes a long, long time for you

to face an enemy after having been made aware of its presence). And the

effects work really well — particularly at the early stages of the game, when

you have to be constantly on the watchout for overpowered enemies who can

dispatch you very quickly if you get ambushed. Somehow, those couple of

seconds allocated for each type of enemy characterize them perfectly in

individual ways — from the busily angry mumble-grumble of the Goblins to the

sheer carnivorous guttural roar of the Orcs; from the ethereal wails of the

Ghosts that somehow manage to combine sadness, surprise, and menace at the

same time to the «advanced» level of the same combo from the Wraiths (who add

a particularly threatening guttural croak to the «cleaner» Ghost tone); from

the cat-like venomous hissing of the Spiders to the

«never-a-moment-of-peace-for-poor-me» constipated moans of the Ghouls; from

the calm, cool, and collected pitch-black-deep roar of the fire-breathing

Hell Hounds to the terrifying battle scream of the Vampire — I’d really like

to give out a hug to whoever designed (and voiced!) those effects. Not only

are they cool per se, they are also, to a certain degree, unpredictable, and

not always corresponding to the usual stereotypes we associate with these

kinds of enemies. Finally, the full CD-ROM edition of the

game throws in a bit of voice acting — specifically, a female voice for the

visions you get from Ria Silmane (allegedly provided by one of the female

programmers at Bethesda) and an unknown male one for Jagar Tharn (who also

only appears in visions). Tharn’s actor overstates his function a bit with

way too much mwahaha, look at me I’m so

evil! pizzazz, and Silmane’s voice is rather monotonous and emotionless,

but neither performance is cringeworthy, and I find it almost surprising how

much they actually contribute to the atmosphere — even with their relatively

rare appearances, they provide a bit of extra urgency and thrill that is very

much needed to alleviate the robotic mechanicity of the miriads of

identity-less NPCs in the game. (Why they never bothered to add any voice

acting to Daggerfall beyond the

opening scene is a mystery to me — surely this would have been even easier to

do in 1996 than in 1994). I am sure that a lot of Arena’s audio charm has to do with

the slightly «amateurish» nature of the game — with the Bethesda team

plunging into the genre without any previous experience, and with PC-MIDI

technology still relatively fresh, they were not nearly as dependent on

fantasy game clichés as just about everybody has been for the past

twenty years or so. What other players might, therefore, dismiss as a

naïve early approximation to how a fantasy RPG might sound, I prefer to

approach as an inventive and occasionally unconventional take — giving the

game its own unrepeatable flavor. Ironically, much, if not most of this

soundtrack would later be carried over to Daggerfall as well, but while the older tracks would be augmented

by a whole bunch of new soundscapes, none of them would quite match the weird magical effect of the Arena compositions — almost as if Mother Nature wanted to show us

how «inspiration» eventually settles into «routine» (although I still prefer

most of what Heberling, with his more «playful» approach, did for the series

to Soule’s «monumentality» that started with Morrowind and continues on to this very day). |

||||

|

In terms of general gameplay, Arena did not revolutionize the

traditional RPG mechanics in any obvious way I could think of. From the

start, your character has the same standard set of parameters that most RPG

experiences have, some of which are more important for one group of classes (Strength,

Vitality, etc. for a Fighter-type class) and some for others (Intelligence

for a Mage-type class, etc.), and all of which are influenced by the relative

luck of your initial rolls (during character creation) and subsequent ones (when

you level up). XP for leveling up is harvested in a very simple way — by

killing monsters and absolutely nothing else — but the good news is that in

order to beat the main quest in Arena,

you don’t necessarily have to grind: as long as you do not arm yourself with

a walkthrough and make a straight beeline for your coveted target in any of

the main dungeons, instead of exploring them meticulously and mopping up all

the monsters, you are guaranteed to level up rather smoothly. People often

complain about the opening dungeon being too hard, but I never experienced the

same kind of problems with it as I did with Daggerfall (where it is indeed recommended to quickly find the

shortest way out of the dungeon as soon as possible). The main interface, with a grid of

options at the bottom of the screen, is convenient enough to be operated

either with the mouse or with some nifty keyboard shortcuts. If you want to

cast a spell, for instance, you click on one of the options to open up a menu

of available spells in the bottom right corner of the grid, leisurely choose

the spell (since opening the menu pauses the game) and blast the enemy; later

on, you can press a shortcut key to re-cast the spell rather than reopen the

menu again (this is my preferred way of healing myself — if you have enough

mana, patching yourself up right in the middle of combat with even your

toughest enemies can be a cinch). If you want to save mana and use up a

charge on one of your magic objects (some of which you can also loot in

dungeons, while others can be bought for astronomical sums at blacksmith

shops — I am personally much more

of a seller than a buyer in this game), you open up a similar list of

artifacts in the same window, although, to the best of my knowledge, this is

an action for which there is no keyboard shortcut. Moving around is performed with the aid

of a map (which opens up in a separate window) and a compass; the map is

fairly simple compared to the 3D vision-breaking monstrosities of Daggerfall, and you can even make

nifty little notes, for instance, to mark the locations of valuable loot if

you are already overloaded and want to come back later. If you want to travel

from one town to another, you open up a separate «maxi-map» of the provinces

of Tamriel where you circulate between locations. Travel itself is fairly

uncomplicated — it merely eats up your time — and the only drawback is that

there is never a set time for your arrival anywhere, so you may very well end

up at your destination in the dead of night (and be immediately attacked by a

bunch of bandits or ghosts). Dungeon-crawling is generally not too

complicated, and the «good» news is that there is practically no way to die

in any dungeon other than be killed by enemies — you cannot starve, you

cannot hurt yourself by falling into a deep pit, and you cannot drown in any

underground water current (unless you happen to be paralyzed by a spider

while in the water, in which case you instantly drown — one reason why my preferred

character race in Arena is always High

Elf, as these guys are naturally immune to paralysis). Oh, right, you can drown in a river — if it happens

to be a Lava Current, that is, and you have no spells or potions that could

make you resistant to fire. One reason, however, why I tend to avoid swimming

if at all possible is that this happens to be one of the most bugged areas of

the game: much of the swimming takes place under the stone floors of the dungeons (not sure how this is

possible physically, but that’s 3D game magic for you), and if you happen to

emerge in a place guarded by an overhead enemy, you tend to get stuck, unable

to do anything while the ruthless fiend pulverizes your health bar from

above. (The same can also happen when you fall down a pit and navigate the

underground passages in one of the game’s «mine-type» dungeons, so beware!). Speaking of bugs, the original game was

quite heavily criticized for their variety and game-breaking potential —

something that would later go on to become more or less a staple for the Elder Scrolls series in general, but

can, perhaps, be excused as an almost inevitable consequence of an unhappy

marriage between Bethesda’s limited resources and limitless ambitions. In any

case, playing the game decades later on DOSBox, where just a bit of twiddling

with the settings gets the game to run quite smoothly on PC, was more or less

a walk in the park for me. Yes, the combat thing is very primitive — all you have to do is wave your mouse around the

enemy, mash the attack button and pray your hit connects — but then,

precisely how much more primitive is this than the shooting mechanics of Doom, or just about any random shoot-’em-up

/ beat-’em-up game in which the quantity

of mowed-down enemies matters more than the quality of the actual fight? Essentially, most of the complaints

about the playing mechanics of the game are exactly the same as applied to

any other RPG. For instance, the loot system: for your first couple of

dungeons, you shall probably be excited at every single stash of loot you

find around the place, but pretty soon you’ll get overloaded with tons of

useless crap, all of it likely inferior to the weapons and armor you are

already equipped with, and will either have to drop it or waste time hauling

it over to various shops to bargain with the merchants (actually, there is

only one type of merchant in Arena, always conveniently doubling

as a blacksmith). Eventually, you’ll have way more money than you really need for anything, at which

point collecting loot will simply be an optional bore. Another thing is the

already mentioned «Spell Construction Kit» — an idea that sounds good in

theory, but is absolutely useless in practice, since you can easily achieve

any goal in the game by simply using whatever is pre-available at your local Mages’

Guild. But in fact, complaining about these things is not too honest, either —

they are completely optional, as, for that matter, is almost everything else

in the game that is not directly related to the goals of the main quest. |

||||

|

Verdict: A simultaneously

humble and ambitious start to the Elder Scrolls saga — one in which

atmosphere matters more than historical importance. You may have noticed that throughout this review, I’ve been

surreptitiously throwing out little jabs at Daggerfall, the second game in the series — but not so much to

undermine the legend of this fan favorite as to point out that, contrary to

popular opinion, upon release Daggerfall

did not, in fact, make Arena fully and completely obsolete

and redundant. In trying to do more, more, more, more than Arena, the

same way that all the games in the GTA

series would try to insanely expand the amount of choice available to players

of Grand Theft Auto III, Daggerfall ended up losing some of

the first game’s atmospheric charm and «primitivism». I actually like, for

instance, how the Main Quest of Arena

is structured like a compact piece of some traditional Greek or Indian mythological

epic, where Daggerfall, on the

other hand, would plunge straight into all sorts of quasi-medieval political

intrigue where you would soon lose the multiple threads of whatever was going

on. I am more or less satisfied with the limited number of side quests that

can you pick up — as uniform and monotonous as they are, they feel a bit more

honest than Daggerfall’s simulation

of an incredible diversity of tasks which, nevertheless, still amount to the

exact same thing (visit a dungeon, mop up all the occupants, find something /

someone and bring it / him / her back). And that sonic atmosphere of Arena... say what you will, but there

is still nothing like it in subsequent games. There

is a funny paradox embedded inside Arena:

while — purely formally — being the biggest

game in the entire saga, the only one in which you can explore the entire

continent of Tamriel and map out its contents for literally years and years, it is also the smallest in terms of actual original content. Outside of the

sixteen dungeons of the Main Quest, there is little to do in Tamriel other

than simply walk around Tamriel, be a ramblin’ man, trying to make a livin’

and doin’ the best you can. Some will rightfully say that this is a somewhat

cheap attempt to deceive the player, lure you in with promises of a huge

sprawl, all of which turns out to be generic, repeatable routine (hey, sounds

just like real life for most of us, doesn’t it?). But as long as you are

properly forewarned — disregard the hype, only believe 100% verified

information! — there’s a certain kind of charm, too, in this «simplicity-over-complexity»

approach, where you can feel

yourself being a tiny grain of sand in a huge, infinite world while at the

same time realizing your own epic importance in a save-the-world-from-tyranny

kind of mega-quest. It’s

funny to realize that with all the technical and substantial progress in the

art of video gaming, the one thing that modern RPGs are no longer capable of

replicating by definition is that exact feel — simply because it would take

too many resources and too much work for a procedural generation of an Arena-type world on the modern level

of gaming demands. This is neither a good nor a bad thing; it only means, as I

never cease to repeat while writing either about music or about video games,

that certain types of sensual experiences are exclusively confined to their respective eras (in this case — a

particular, very short, time window in the mid-1990s), and that losing the

opportunity to wind up a game like Arena

on one’s computer would mean losing access to a pretty unique type of sensual

experience indeed. Fortunately, with Bethesda having released Arena as freeware quite a long time

ago, there is little danger of that as long as there is at least a single «Eternal

Champion» running around with a DOSBox emulator. [Technical

note: You can clearly see how much more popular Daggerfall remains in the hearts of gamers through the sheer fact

that there is a complete and fully working modern version of Daggerfall, written by loyalfans in

the Unity engine, openly available to the public — however, the parallel OpenTESArena project,

having started around 2016, still remains in its initial stages and does not

even have a fully playable demo. Honestly, I do not hold much hope, but I can

at least dream that some day

freedom fighters around the world might be able to resume their hunt for the Staff

of Chaos in a smooth, perfectly running and bug-free modern graphic

environment.] |

||||