|

Gabriel Knight: Sins Of The Fathers |

|

|||

|

Studio: |

Sierra

On-Line |

|||

|

Designer(s): |

Jane

Jensen |

|||

|

Part of series: |

Gabriel

Knight |

|||

|

Release: |

December 17, 1993 |

|||

|

Main credits: |

Producers: Robert Holmes, John E. Grayson Artists: Terrence C. Falls,

Darlou Gams, Gloria Garland Music: Robert Holmes |

|||

|

Useful links: |

Complete

playthrough (11 parts, 690 mins.) |

|||

|

Gabriel Knight: Sins Of The Fathers is, without question, the

best adventure game ever made by Sierra On-Line. With some questions, it might actually be one of the best video

games ever made by anyone, period. Of course, in terms of substance it

suffers from exactly the same flaw as any other great (let alone not great) video game — namely, lack

of conceptual and literary depth, a problem that has not been overcome by the

genre even a quarter century later. But in terms of style, atmosphere, and general

player involvement, I believe, Gabriel

Knight has very few equals. That this level of quality

could have been achieved in 1993, a year in which plot-based video games were

still essentially in their infancy, is largely due to the talents, energy,

and efficiency of one single woman: Jane Jensen. Having already worked as

assistant writer on some of Sierra’s earlier games, and having cut some

serious teeth as co-designer first for Gano Haines’ Eco Quest and then, in a major function upscaling, on King’s Quest VI, Jane eventually

gained enough reputation to be given her own project. When she came up with Gabriel Knight, a supernatural mystery

based around New Orleanian Voodoo, Ken Williams was allegedly not too

enthusiastic about it — perhaps the story sounded too dark for

family-friendly Sierra, or perhaps he was jealous of Jensen coming out as a

competitor in the mystery genre to Roberta Williams (who had previously been

Sierra’s leading «mystery expert», from the faraway beginnings of Mystery House, Sierra’s first game, to

the more recent games in the Laura Bow

series). Regardless, being the human-like rather than machine-like business

manager he was, willing to take risks whenever his gut feelings told him to

take ’em, Ken gave Jensen the permission to assemble her own team for the

project, and even provided her with a fairly substantial budget for the whole

thing. And it was well worth the investment,

because there was one little element that Jane brought to the table which was

hitherto lacking in Sierra games — maturity.

Naturally, those games had fairly mixed audiences of all ages, and some of

them were clearly oriented at a more adult slice of population than others (Leisure Suit Larry), but «adult» and

«mature» are hardly synonyms. Gabriel

Knight was the first Sierra game to (almost defiantly) grow out of a

simplistic, pampered model of interaction with the player and explicitly

target those who had been holding their breath, waiting for computer games to

begin reaching at least the level

of B-movies when it came to plot, characters, dialog, and suspension of

disbelief. LucasArts may have been on the brink of doing that for comedy, but

what about less laugh-oriented genres? Sure, there had always been

interactive fiction of the Infocom variety — the true pride and glory of

digitally oriented nerds all over the globe — but that’s more or less as if

the only «serious» cinema experience to be had in the 20th century were to be

restricted to silent movies. You want Cinema as Art? Go watch some Murnau.

You want Video Games as Art? Go play Zork. Gabriel

Knight may not have

been the only, or even the first, game to change all that, but it was the

first Sierra game to follow a truly new vision, and with Sierra still being a

leader in plot-oriented videogaming at the time, it might be difficult to

overestimate the influence it had on everything that followed. But it is not

its influence that amazes me — rather, it is how well it still holds up after

all these years, due to a large combination of factors: Jane’s storytelling

skills, her ability to create a roster of memorable characters (even minor

ones!), the beautiful art of the game, the atmospheric quality of the music,

and, of course, the terrific voice cast assembled for the project. Everything

aligned to such near-perfection that when, 20 years later, it was announced

that Jane was busy with a remake of the original game to bring it up to

modern standards — a complete remake,

not a remaster — I knew from the start that I would end up disappointed, and

I did end up disappointed, just the way I would probably be disappointed if

the Beatles all lived and gathered together 20, 30, or 40 years later to

«remake» Revolver or Sgt. Pepper. Simply put, you do not

mess with the classics. As far as I can tell, the game was not

a huge seller upon release; if Jane had any hopes of beating Sierra’s King’s Quest records, they were

quickly quashed — after all, putting the focus on «maturity» was maybe not

the best possible move from a purely marketing point of view, and Sierra’s

fanbase, used to the relatively lightweight nature of the games, may well

have been put off. (Then again, actual truth may be simpler — two years

later, the much darker and much more inferior Phantasmagoria became a best-seller

after a fairly aggressive marketing campaign by the Williamses, so I suspect

that Gabriel Knight simply did not

get enough promotion... after all, it wasn’t a Roberta Williams game, was

it?). But it was a major critical favorite from the start, and in 1994 it

went on to share Computer Gaming World’s top prize for Adventure Game of the

Year with Day Of The Tentacle —

possibly the single greatest double billing in gaming history. A quarter century on down the line, the

legend of Gabriel Knight has

predictably become covered with museum dust, and modern gamers,

unfortunately, are more likely to make their acquaintance with the game

through the graphically enhanced, but substantially neutered 20th Anniversary

remake. I might do a separate review of the remake later, as much as it pains

me to do that, but for now, let us pretend that it never even happened, and

just concentrate on the original classic. |

||||

|

Content evaluation |

||||

|

Jane Jensen’s Gabriel

Knight, whose very name screams out a burning desire to escape into a fantasy

of medievalist values and chivalric virtues (and vices), comes from a long

line of antiheros and chosen ones, and while my rather miserable knowledge of

the Gothic novel or of the bestselling American supernatural mystery fiction

of the 1990s prevents me from identifying Jensen’s main influences, it is

probably safe to say that the basic plot of the game is not particularly original

(in fact, in terms of sheer inventiveness it pales quite significantly next

to the second game in the series, The

Beast Within). Still, it is original enough for us not to be able to

predict every twist and turn of

Jensen’s pretty convoluted story — you shall probably start putting together

pieces of the puzzle as early as the very first day in the game, but the last

ones will not fall into place properly until very close to the end. Anyway, the plot in a

nutshell: you play as Gabriel Knight, a financially struggling 33-year old

pulp novelist and owner of a used book store (‘St. George’s Books’!) in the

French Quarter of New Orleans. Not being able to hit the big time with his

writing at all, Gabriel eventually latches on to a series of brutal ritualistic

murders in his home city, which may or may not have been perpetrated by a

secret cult of dark Voodoo practitioners — at first, merely in hope of

finding some inspiration for his next novel, but eventually realising that

whatever is going on may actually have a strong connection to his own family

past, as well as the recurrent nightmares from which he has been suffering in

recent times. With the help of his trusty sidekick, the Japanese-American

university graduate Grace Nakimura, and his somewhat bumbling childhood

friend, Detective Franklin Mosely, Gabriel begins to slowly unravel the

mystery of the murders — which does lead him to the cult in question, as well

as a gorgeous and rich femme fatale by the name of Malia Gedde; a long-lost

uncle with tall tales to tell; a mysterious medieval castle in the depths of

Bavaria; a haunted archaeological dig in the Republic of Benin; and an entire

array of colorful New Orleanian characters, each with his or her own

skeletons in the closet or, at least, a closely guarded secret or two. The story unwinds over the course of 10

in-game «days», rather slowly and leisurely at first, with each day holding

multiple events that have to be passed in order for night to fall upon the

city. Once Gabriel begins to understand what is really going on — an evil plot unfurling almost literally under

his feet, putting most of the world’s conspiracy theories to shame — time

begins to speed up, with the last few days of the game spent in a frantic

race to prevent the impending catastrophe; also, while the majority of the

game (the first 6 and a half days and the last one) is spent in New Orleans,

toward the end Gabriel has to leave the comfort (or, at that moment, the discomfort) of his home city, first

for Germany and then for Africa, introducing a bit of an Indiana Jones flavor

into a game already well-spiced with Hitchcockian motifs. Compared to the

detailed, dragged-out New Orleanian sequences, this part definitely has a

rushed feel to it — I think the designers either got tired or had to rush to

meet the Christmas deadlines — but it is all made up for in the final

climactic sequence, when Gabriel finally tackles the bad guys head-on. If you have never played the game and

all of this smells a bit funny — indeed, one of the chief accusations one

could fling at Jane Jensen is that she must have spent way too much time watching movies from the first half of the 20th

century for a game designer working at the tail end of the 20th century —

anyway, if you think it all sounds like too much silly childish crap for a

supposedly «mature» game, I might even grudgingly agree, but there are still

two important counterarguments to be made. First, what separates Jensen from a lot

of game writers exploring similar historical topics (such as, for instance,

Charles Cecil of the fun, but overrated Broken

Sword series) is her relatively in-depth exploration of the subject. By

no means is Gabriel Knight a

genuine «edutainment» project (à la Conquests series by Sierra’s own Christy Marx, for instance), but

neither is its treatment of Voodoo primitively cartoonish. Certainly the idea

of a «black Voodoo cult», with human sacrifices and shit, looks borrowed from

antiquated horror movies like White

Zombie more than anything else, but (a) use of black magic in Voodoo

practices is, after all, just as real as Satanism or similar dark practices

in any religion and (b) the game explicitly places its evil plot within a

much more general context of pagan practices, including an impressive amount

of fully historical information on Louisiana Voodoo, its Haitian and

ultimately African roots (which it calls Voudoun

instead of the more commonly used Vodou

or Vodoun, but let us not be too

picky). Jensen’s main talent, however, is not

simply in doing her history and anthropology lessons, but in skilfully

interweaving that historical data into her own narrative — so much so that,

unless you have been an exceptionally good student yourself, you might have a

hard time distinguishing fact from fiction in her narrative, where perfectly

historical characters like Voodoo Queen Marie Laveau and perfectly well

attested events like the Haitian Revolution of 1791 are mixed with fictional

heroes (such as the Gedde family) and fictional events (like the 1693

«Burning of Charleston»). A common trick Jensen uses in all of her Gabriel Knight games is coming up with

a supernatural explanation of some of history’s unresolved mysteries, and

while I do believe that she hit her peak in this particular enterprise around

the time of the second game, Sins Of

The Fathers still does an excellent job at presenting its «alternate

model of para-history» without actually disrupting or contradicting the

historical narrative as we know it. The second excellent aspect of the

game’s story are, of course, its characters. For the first time in a Sierra

game and, perhaps, for the first time in any

computer game, not only the title character, but also most of the NPCs

surrounding him feel like living, breathing personalities rather than sketchy

digital sprites — even the episodic shop owners, bartenders, grave keepers,

and minor Voodooiennes who only appear in the game for an event or two have

their own bits of back stories, dreams, aspirations, emotions, whatever. As

is often the case with great story-based games (and not only games), it does

not truly matter what kind of story

is being told; what matters is how

it is being told, and the detalization, complexity, and elegance of Jensen’s

dialog still remains a high point in the history of video game evolution. Gabriel Knight himself is quite a

fascinating character, unusually difficult to pigeonhole. Like most of Jane’s

characters, he lives in a bit of a time bubble (working at a typewriter as

late as 1993, for instance, and staying blissfully ignorant of pretty much

any modern trends — heck, even his own bookstore mostly carries "pulp

novels from the 50’s and 60’s"), but manages to be an (allegedly

successful) womanizer (though, luckily for us, we do not get to see any of his conquests). He can be

tender and caring one moment and an unbearable, though still lovable, asshole

the next. He may be ruthless in achieving his goals, but only because he

believes in the ultimate Great Goodness of these goals. His motivation is

sometimes egoistic, sometimes altruistic, and sometimes a bit of both at the

same time. He can come across as a male chauvinist pig to quite a few players

and even reviewers,

mainly due to his «sexist» remarks to his secretary, Grace ("well... if

the Devil had great legs, perhaps... like yours!"),

yet it should not take long to realize that the «sexist talk» is nothing more

than a humorous, and completely consensual, game played out between Gabe and

Grace for their own and our amusement, since both characters clearly have the

highest respect for each other. Even when he «officially» aligns himself with

the Light, joining the ranks of the mythical Shadow Hunters, this does

nothing to cure him from a generally sarcastic and mischievous attitude,

behind which actually hides a genuine desire to do good... or is it really

just a genuine desire to get that girl at all costs? Who really knows? Speaking of Grace, let us, perhaps, not

forget that it is Jane Jensen’s Grace Nakimura, rather than Lara Croft or any

of those ridiculous JRPG anime dolls, who would be fully deserving of the

title of «strong female character #1» in 20th century video games, if only

all these endless best-of lists of video games did not tend to treat the

adventure game genre much like best-of lists of popular music tend to treat

progressive rock. Even if Sierra itself already had quite a roster of

memorable female characters, from Princess Rosella to Laura Bow, Grace

Nakimura is the first female character in Sierra history to actually think,

talk, and act like a real living, breathing woman made of flesh and blood,

and even if she is not directly playable in Sins Of The Fathers (Jane would eventually correct that with the

second and third parts of the trilogy), she still feels like an inseparable

part of the detective duo, complementing those parts of Gabriel’s soul which

might feel deficient ("Is Grace your wife?", our hero gets asked

after namedropping her one too many times; "No, she just acts like it",

he responds without batting an eye). At the end of the game, she does have to

fulfill the function of damsel in distress — but not before explicitly

pulling Gabriel’s ass of the fire several days earlier; equality of sexes,

definite check. Pretty much every single character in the game, or, to be more accurate,

every single character awarded with a close-up portrait and a set of dialog

options, turns out to be more than one-dimensional. Grandma Knight, the

sweet, lovely, and cuddly Southern belle, has a dark skeleton in her family

closet. Dr. John, the intimidating owner of the Voodoo Museum, is extremely

polite, well-spoken, and erudite. Madame Cazaunoux, the batty old Creole

lady, hides a deep feeling of mournful nostalgia for the French community of

New Orleans behind her ridiculous mannerisms. Gerde, the seemingly

superficial and light-minded German servant at Schloss Ritter, is in fact

torn apart by the love for her master. Good guys have their dark spots, and

evil characters have a clear motivation for their evil nature — driven,

perhaps, not so much by their general desire to burn down the world as by a

very specific quest for vengeance. Once again, none of this is any sort of

great news when we are talking literature or even movies, but to see this

kind of depth in a computer game around 1993 was deeply unusual — which is

why, when watching old promotional videos for the game and hearing constant

boastful talk about an allegedly new era of interactive fiction / movies

promised to humanity by the likes of Gabriel

Knight, these promises do not really come across as unsubstantiated hype;

instead of feeling offended by the hyperbole, I feel a little sad that even

today, plot-based video games have not really advanced far beyond this level

— largely because neither the public at large, nor the game designers and

studios have succeeded in creating sufficient demand for it. But this is, of

course, a topic for a separate discussion, one which would involve drawing a

straight line from Gabriel Knight

to, say, The Witcher 3 and... okay,

we’re not here to get depressed, but to pay tribute to an amazing piece of

video game art, so enough theory and onwards with the nitpicking. |

||||

|

With all the hubbub about

the imaginative story and the maturity of the writing, it is almost easy to

forget that Gabriel Knight is first

and foremost an interactive game, to advance in which you have to explore,

find clues, and solve puzzles. Solid dialog and haunting atmosphere are nice

and all, but most of your gameplay (without a hint book or walkthrough at

hand) will be likely spent on wondering what the hell to do next rather than

admiring the vistas or reveling in the idiosyncrasy of Tim Curry’s

performance. So, how does Gabriel

Knight actually stack up as a game,

as opposed to a visual novel? Answer: it does... okay.

Clearly, Jane Jensen is a better storyteller than puzzle designer — simply

because the challenges you have to face in the game do not strike me as

particularly brilliant, innovative, or even, well, challenging, certainly not

next to just about any other aspect of the game. As a rule, your daily

activities will be typical for those of any investigator: rummage around for

clues and useful objects, talking to people for precious information, and

putting two and two together. You are generally free to roam from place to

place; all the action takes place over a set amount of days, and whenever you

have accomplished all the required objectives for Day X, nighttime is

triggered and you are automatically carried over to Day X+1. This is a nice

way of marking progress, though it does result in some odd discrepancies

(some days take an excruciatingly long time to complete, others pass by in a

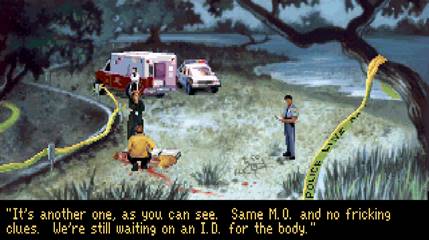

blink of an eye). Rummaging around is, of

course, an art that mostly comes in handy at crime scenes or suspicious

undercover locations, and it inevitably involves some degree of pixel

hunting. The most commonly voiced complaint, I believe, is about the scene at

Lake Pontchartrain, where you have to find one specific tiny area in a clump

of grass that has a "matted appearance", so that you can pick up a

piece of evidence which will later help you to tie the crime to a definitive

suspect. The area itself is almost

unidentifiable on the large screen, at least not until you scour over

everything with the magnifying glass — yet I am not entirely sure whether

this truly constitutes «bad design». You are, after all, at a crime scene

which has only recently been investigated by a squad of police officers —

would you expect them to leave around a piece of evidence easily detectable

to the naked eye? It makes perfect sense that an extra investigative effort

is required here, as long as you get a clear hint that you may be supposed to find something that your

good friend Detective Mosely has missed — and with that hint at hand, I never

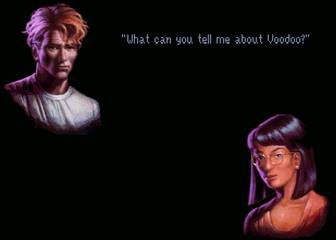

had a serious problem with that puzzle. Conversing with other

characters is not simply encouraged, but is, in fact, obligatory: every now

and then, talking to a certain person about a certain topic (e.g.

"Voodoo") opens up another possible topic (e.g. "Black

Voodoo") which is, in turn, necessary to butter up yet another person.

The original list of topics in the dialog tree is relatively small, but as

the game progresses, new and new options open up, so that by the end of the

game the dialog options cover the center of the screen from top to bottom. If

you are not Mr. Dialog Guy, this line of work might easily seem tedious to

you; but the correct way to play Gabriel

Knight is to play it for as much dialog as your eyes and ears can carry,

so, to me, this is pretty much that particular chunk of the game that largely

plays itself. (Do not forget that certain topics may, or even need, to be

explored more than once with the same character — you should click on

everything until the NPCs start repeating themselves). The truly fuzzy areas of

the game, of course, are those which require you to put away the tried and

true algorithmic methods and begin thinking out-of-the-box. There is not a

lot of them in the game, but there are perhaps 5–6 situations where you might

seriously get stuck... in a discussion, that is, over who is more stupid, the

incompetent player or the inane puzzle designer. For instance, the infamous

«Drei Drachen» puzzle requires you to establish and confirm a connection

between a line of poetry randomly found in one of the books in your used book

store and the correct way to open

up your grandfather’s clock, dusting away in Grandma Knight’s attic. (Even

more annoyingly, unless you have a basic knowledge of German, you not only

have to find the book itself, but also a nearby German-English dictionary to

help you with the translation). Is this logical? Is this solvable? Is this

acceptable? I honestly cannot tell, though I do confirm that it was quite

solvable for me without any hintbooks. It does certainly conform to Jane’s

vision of Gabriel’s character: in The

Beast Within, Mrs. Smith, reading Grace’s and Gabriel’s Tarot, concludes

that "your (Grace’s) card is

all logic and reasoning, while his is spiritual and intuitive". This

probably means we shouldn’t really pout about a few of these puzzles being

based more on intuition and association than stone-cold logic. A couple of the puzzles are actually

«puzzle-ish» in nature: for instance, in order to learn the location of a

crucially important Voodoo ceremony and be able to track its participants

Gabriel needs to (a) decipher a secret Voodoo code off Marie Laveau’s

tombstone and (b) use a book on Rada drum codes to understand the relay

drummer’s message. Still later on in the game, he will actually have to

compose a Rada drum message himself (sidenote: the whole Rada drum thing is

another example of Jensen’s wicked weaving of fact and fiction — ceremonial

drums are a natural staple of the Haitian tradition, but the existence of a

special drum code for transmitting specific information seems to be her own

invention). The first two parts of the puzzle are fairly easy on the player;

the third one, again, requires a bit of the old out-of-the-box thinking and a

bit of that intuitive / associative reasoning to pull off perfectly... but

hell, I got it right on my own first try. Maybe I was just born to be a Schattenjäger, who knows.

(Actually, the only time I found myself really stumbling in the game was that

damned tile puzzle in the African hounfour, where, believe it or not, you are

once again required to remind yourself of the Three Dragons line — the good

thing is, you can at least solve it by sheer trial and error over a

permissible amount of time). As in all Sierra games, some actions in

the game remain optional and are only required to get a perfect score; the

good thing is, most of them are

fairly logical, and you’d be dumb not to try them out (like exploring all the

locked rooms in the New Orleans hounfour, for example, or searching the

dropped veil of a certain snake owner for extra evidence). Even better,

Jensen had clearly looked at enough LucasArts games to design the game in

such a way that it never puts you in an unwinnable state — any important

object you have missed can be picked up at any time, and if it can be picked

up only at a specific time, the day will never end until you have picked it

up. At least one puzzle (getting into your friend Mosely’s office after he’s

been evicted from it) may be failed by not getting the timing right — but the

good game will offer you a cop-out anyway (the desk officer will simply fall

asleep), although you might not get the perfect score as a result. Despite the darkness and danger lurking

everywhere, Gabriel Knight does

distinguish itself from the majority of Sierra games by featuring very few

death situations — in fact, no matter where he pokes his nose into, Gabriel

officially cannot die until Day 6 of the game (when you do die, it comes off as quite a shocker!), and it is not until

the very last day, during his infiltration of the Voodoo coven, that death

traps become common: the final climactic scene, in particular, requires

lightning-fast thinking in order to avoid being pummeled by your

arch-nemesis, the evil spirit Tetelo. (My main beef with that scene is that

you never have enough time to read and listen to the various descriptions of

the scene’s elements by the Narrator — all you gotta do is act, act, act, and

act quickly!). I do not actually disagree with that philosophy — it ties in

fairly well with the idea that the meat’n’potatoes of any good thriller is

the suspense and tension, while the final release has to come on quick,

relentless, hard, and brutal. And, apparently, neither does Jane, considering

that the exact same ratio of death to life was strictly observed in the next

two Gabriel Knight games as well. All in all, the challenge provided by Sins Of The Fathers is nowhere near

the level of difficulty of its prime competitor, Day Of The Tentacle, but there is still enough challenge to feel

yourself, every now and then, in the shoes of a real investigator of a murder

mystery, if not necessarily in those of a supernaturally endowed Servant of

the Light (and I am grateful to

Jensen that she refrained from turning Gabriel Knight into a wielder of magic

wands or a drinker of alchemical potions: these games operate on a whole

other level than Harry Potter or The Witcher when it comes to

distinguishing between the mundane and the supernatural). |

||||

|

Gabriel Knight would not be Gabriel

Knight, that is, one of the best games of all time, without its unique

atmosphere — however, despite most of the game formally taking place in New

Orleans, it must be admitted that the atmosphere in question is not

particularly New Orleanian. Fascinated as she was with some aspects of Creole

culture, not to mention both the popular and the historical perceptions of

Voodoo, Jane Jensen had never been to New Orleans herself (which is sort of

amusing, because for her next games she did

visit both Munich and Rennes-le-Château), and although the game does

feature some of the city’s notorious landmarks, such as Jackson Square, St.

Louis Cathedral, and the St. Louis Cemetery #1, most of the action takes

place indoors, in settings that could be New Orleanian, or generally

Southern, or just about anything. Jackson Square, where you will run into

musicians dutifully performing ‘When The Saints Go Marching In’, artists,

jugglers, and pesky mimes, is probably the most authentically atmospheric

depiction of the place, but Gabriel hardly ever comes there to mingle — it’s

mostly all detective business. In any case, the game is

not about New Orleans as a wholesome cultural experience; it is all about

that elusive «darkness on the edge of town», slowly and subtly constructing

an atmosphere of impending doom around the title character — and, through

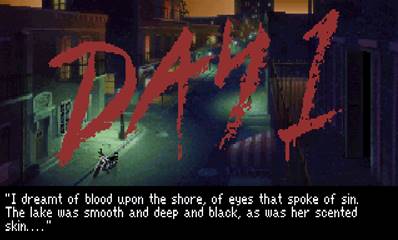

him, around you, Mr. Player. The scene is already set by the opening

sequence, as a sickly-looking morning sun rises over the deserted Bourbon

Street and the huge title "DAY 1", written in blood letters, is

strewn across the screen, accompanied by the first line of Gabriel’s future

poem ("I dreamt of blood upon the shore, of eyes that spoke of

sin..."). Of course, the very next sequence is that of Grace sitting in

her nice cozy chair at her nice cozy desk, inside Gabriel’s nice cozy store,

comfortably chatting away on the phone with one of Gabriel’s sweethearts

("I’m sorry, but Gabriel is a lout, oh, I mean, he’s out"), while

the shop owner (you) clumsily stumbles out of his bedroom to grab a cup of

coffee. But this total normality of the situation does not in the least feel

normal after that opening sequence — and if there is anything that Grace and

Gabriel’s opening conversation really brings to mind, it is the barbed

exchanges between Johnny and Midge at the beginning of Hitchcock’s Vertigo, one of several classic movies

that must have been a big influence

on Jensen in her creative process. This juggling between

coziness and faint whiff of impending danger is the main element creating the

game’s atmosphere. For the first — and longest — three days of the game, the

most disturbing moments in Gabriel’s life take place at night, with a

recurrent dream involving people burned alive, people changing into leopards,

snakes, knives, and somebody who looks disturbingly like Gabriel himself

hanging from a tree. By daytime, Gabriel is mostly safe — mostly, because you never know when to

expect a small jump scare (like, from a random street performer) or a

mini-nightmare (like, while falling asleep at a boring lecture on Voudoun at

Tulane University). Still, these moments are very rare, especially when

compared to the amounts of perfectly normal conversations with the city’s

denizens. Intrigue is mostly accumulated by gradually understanding that something is happening here, but you

don’t know what it is, do you, Mr. Knight? — and, most importantly, you do

not know whether this truly has to

do with some supernatural evil at work, or if it is some unspoken evil in the

hearts of plain ordinary men that we find ourselves fighting against. In all honesty, I would say

that once Gabriel does achieve clarity and confronts the century-old Voodoo

curse head-on, this is precisely where the game begins to lose ground in

terms of atmosphere. It still works, but its straightforward transition into

the world of magical mumbo-jumbo seems half-assed and slurred, compared to

the meticulously constructed intrigue of Gabriel’s and Grace’s five-day

investigation. As a historian turned storyteller, Jensen gets top grade

marks, but as a mystic, she does not really advance past the level of the

aforementioned White Zombie — in

particular, the climactic scenes of the Voodoo rituals at the Bayou and then,

later, in the hounfour suffer from too many clichés and too many corny

lines of dialog ("oh great Badagris, take this sacrifice!" and the

like). A part of me actually wishes that she could have eliminated the

para-normal elements of the story altogether — with a little extra effort,

the game might have been turned into a dazzlingly original tale of age-old

treachery and revenge — but, on the other hand, para-normal works just fine

as an allegory for real world problems in the Gothic novel (Stoker’s Dracula is a classic example), so the

issue is not that Gabriel eventually discovers that evil spirits are real, it

is that these evil spirits look humiliatingly caricaturesque against the far

more colorful portraits of their flesh-and-blood contemporaries. The big

baddie, Tetelo, is basically just a bag of recycled tropes — even against the

portrait of her living descendant, Malia Gedde, as long as she is not

possessed by the old cliché-spouting hag. Still, the good news is

that 90% of the game is spent waiting for shit to hit the fan, and that’s the

really, really awesome part. Some might protest that any work of art in which

the exposition is more enjoyable than the resolution is deeply flawed — but

then, there are situations in which foreplay turns out to be more memorable

than the orgasm, too. For what it’s worth, this may arguably be a thing that

Jane’s work does share with at least some

of Hitchcock’s movies — in many of which the wait for the culmination really

provides more emotional payoff than the culmination itself (which is

delivered swiftly, bluntly, and with a rapid transition to final credits). At

least Jensen, unlike Hitch, allows you to choose one of two endings for your

hero — the path of mutually destructive vengeance, or the path of mercy,

forgiveness, and redemption (of course, only one of the two counts as

«canon», since a dead Gabriel Knight could hardly qualify for protagonist of

the second Gabriel Knight game). And, on a side note, let us

not bypass the humor, either. Gabriel

Knight is anything but a comedy, yet there is enough funniness in it to

sometimes forget the dread and danger. In between Gabriel and Grace’s

incessant dart-flinging game ("I saw a great documentary last night on

pyramid excavations" – "You mean small, dark places that haven’t

been touched in centuries? Sounds right up your alley" – "Well, it

did help me gain a better understanding of your mind"); Desk Officer

Frick’s constantly being torn between devotion to duty and to donuts

("muffuletta sandwiches, yum!"); Gabriel’s interactions with the

wishing stump in the Voodoo museum ("I wish Malia Gedde were permanently

grafted to my thighs..."); his hilarious trolling of the poor priest in

the St. Louis Cathedral ("I’ve had impure thoughts about a woman I

met..." – "You mean thoughts of extreme sexual relations?" –

"Well, not involving animals

or anything..."); and even a set of erroneous phone calls that he can

make at random from his home office ("Hello, St. Genevieve’s Wedding

Chapel, how may I help you?" – "Boy, do I have the wrong

number!") — in between all that, we gain even more intimacy with the

characters, as they, just like us, alleviate their fears and tensions with

humor’s saving grace. And speaking of saving Grace, there is even time for

Gabe to punch a few jokes right before the final fight to the death — in a

fairly casual manner at that, not like a James Bond one-liner or anything. Of

course, it does matter that these jokes are voiced by Tim Curry, which may be

an added bonus for some and an annoying impediment for others — so, on that

note, let us proceed to discussing the more mechanical aspects of the game. |

||||

|

Technical features |

||||

|

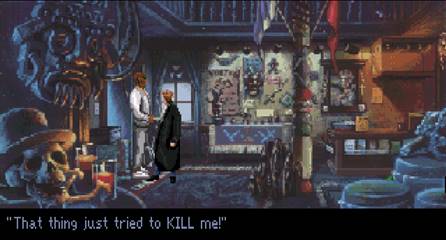

Although visual art

(somewhat predictably, and purely for reasons of technological progress) is

pretty much the only aspect in which the 20th Anniversary remake of Gabriel Knight could improve on the

original, I would still claim that the original graphics, as pixelated as

they are on modern screens, still hold up well. As I already said, the New

Orleans of Jane Jensen is represented mainly by interiors — Gabriel cannot be

seen walking from place to place, other than a brief animation of him getting

on his bike — but the common strategy is to pack these interiors with STUFF

from top to bottom, as if hinting at a special obsession that every

self-respecting New Orleanian must have with quaint and shiny objects of

material culture. Starting with Gabe’s own bookstore, jam-packed with books

and all other sorts of stuff all over the place (including a gargoyle and a

morbid painting by his late father), then going on through the cozy living

room of Grandma Knight, jam-packed with knick-knacks and home plants, then

through the Voodoo shop with all of its candles, dolls, and jars of

unimaginable stuff, then through the Voodoo museum with its dozens of

exhibits... well, you get the drift. It was a good thing that at

least the Windows version of the game supported higher graphical resolution

(640x480 SVGA) — not a huge deal by modern standards, but enough to sharpen

up all those little objects like the tiny tweezers and magnifying glass on

Gabriel’s table, almost indistinguishable in the DOS version. In any case,

the basic art backdrops for the game put a huge emphasis on detalization, an

the results pay off — all through the game, you get the feeling of walking

through a huge antique store. Apparently, one thing that Jane Jensen shares

in common with the abovementioned Charles Cecil of the Broken Sword fame is a (perhaps subconsciously) deep-running

hatred of all things modern — Gabriel Knight is officially set to

take place in 1993, but you wouldn’t really guess that based on the

surroundings (almost perversely and ironically so, the single most

modern-looking space in the game is actually found in the underground Voodoo

hounfour at the end of the game!). Quaint little barrooms with guys playing

chess; old-fashioned cash registers, typewriters, and chandeliers at

Gabriel’s store; 18th century mansions in the Garden District; Creole

stylistics in the house of Madame Cazaunoux — and, of course, the thoroughly

medieval atmosphere of Gabriel’s old family manor, Schloss Ritter, upon his

arrival in Bavaria... all of this is lovingly portrayed by the art team in

such a way as to suggest that you might enjoy this game the best if you

forget the 20th century ever existed. That said, things are still

handled with enough care to avoid truly absurd anachronisms à la Broken Sword (where, for instance, the

French police walking around the streets of a 1990s Paris could easily look

like stereotypical gendarmes from the era of Napoleon III). Many of the

characters you meet in New Orleans are simply old — Grandma Knight, Madame Cazaunoux, the grave watcher at St.

Louis Cemetery #1 — obviously representing the classic, withering and dying

spirit of the city; others, like Dr. John at the Voodoo Museum or Magentia

Moonbeam at the Voodoo Parlour, clearly position themselves as traditionalist

Keepers of the Spirit; and Gabriel’s passion, Malia Gedde, simply has enough

money to allow herself to cling to the past. In other words, if you do not

hear that much jazz music in the New Orleans of Gabriel Knight, it is because the design and art teams want to

actually place you in the New Orleans that predates jazz music, even as the Times Picayune on your desk

reminds you each day that you do, in fact, find yourself straight in the

middle of the summer of 1993. That said, the artists

clearly realized that in order to achieve the required degree of immersion, the

standard backdrops were not enough: they could give you a nice panorama of

the St. Louis Cathedral or a monumental view of the imposing Schloss Ritter,

but they did little to deepen your impression of the game’s characters and

their emotional trajectories. Therefore, in an innovative departure from all

past Sierra practices, Gabriel Knight

makes a special use of close-ups. First, for most of the dialog in the game

the overall backdrop is faded out and replaced by large, detailed, and nicely

animated profiles of the characters — providing each of them with a memorable

visual personality (Gabriel’s hair in particular is quite legendary, but

there is also Grace’s piercing stare, Grandma Knight’s permanently smiling

wrinkled face, cemetery watchman Toussaint Gervais’ magnificent white

beard... way too much to mention). Large-scale facial animations had already

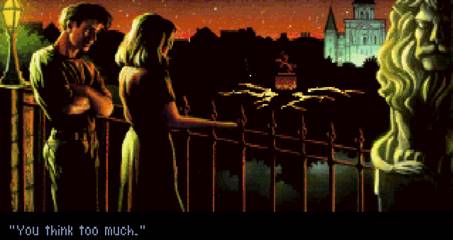

become common in Sierra games by 1993, but with Gabriel Knight they reached an entirely new level of realism. Second, some of the key

events in the game were introduced with a special comic-book style of cut

scenes, in which the scene was gradually filled with sequentially generated

images from one corner to another (this became less efficient, I think, when

faster CPUs began automatically speeding up the process), sometimes also

including minor pieces of animation, like changes of facial expression or

dripping blood. I wouldn’t call the panels «great art» by themselves, but

they did serve a serious purpose — for instance, simply using the overall

panorama during Gabriel’s first meeting with Malia Gedde at Lake

Pontchartrain would never allow to capture the «love at first sight» moment,

whereas the cut-panel approach does precisely that. If I recall correctly, no

other Sierra game would repeat this technique, and I am not sure if anybody

else at the time used it. It can actually be a little confusing upon first

sight, but that’s what replays are for. The bad news, of course, is

that the beautiful close-ups and the inventive cut scenes make the regular

sprites of the characters look particularly grotesque — and that is not even

the fault of modern monitors, but rather the demands of contemporary

animation algorithms, which were unable to handle serious detalisation,

meaning that a coffee-making machine or a typewriter sitting next to Gabriel

will look more recognizable as man-made artefacts than Gabriel will look

recognizable as a human being. This is where something like Day Of The Tentacle clearly wins even

in its non-remastered state, as the intentionally cartoon-oriented style of

that game, paradoxically, allowed for more realism than the diluted sprites

of Gabriel Knight. This is the

element that has always bugged me the most about the game’s style, and

probably the one that ultimately triggered the need for the 20th Anniversary

remake — ah, if only they could have replaced those sprites while keeping in

everything else... but what do we know, demanding perfection from a video

game and all. |

||||

|

Without love, there is nothing; without

sound, there is no Gabriel Knight.

And who knows whether there would have been a sound truly deserving of Gabriel Knight if not for Robert

Holmes, a former LA-based session musician who went to work for Sierra in the

early 1990s and, as it happened, teamed up with Jane Jensen in what became

the single strongest Sierra bond after Ken and Roberta Williams. Not only did

Holmes compose and perform all the music for the game, but he was also

officially credited as its producer. Three years later he and Jane got

married, and he predictably went on to make the scores for all of her games, both during and

after Sierra On-Line. In fact, amusingly, Robert Holmes is not known for much

of anything else other than writing music for his wife’s games — literally

living off her creative genius! That’s okay, though, because of all the

soundtracks written for all the Sierra games I’ve played (and I have played them all), Holmes’ are the

only ones that truly stand out in memory. He would arguably hit his peak with

the second game, but there is no denying that a major reason why Sins Of The Fathers holds you in its

grip from the very opening seconds (right after Sierra’s fanfare) is the

musical opening. Even in its fully electronic, MIDI form, that shrill rising

synth-violin leading into the ominous church bell toll immediately

communicates the message that you are into something a bit more serious than

saving Princess Cassima from her tower or guiding Roger Wilco on a

garbage-towing mission. Echoes of Bach and Wagner can be heard in the melodic

structure and layering of the main theme track, and when the rock percussion

joins in, the effect is a bit similar to the one produced by ‘Live And Let

Die’, though, admittedly, a single guy producing an epic track on a MIDI

synth can only get to a certain distance away from Paul McCartney and George

Martin working on an epic track at the EMI Studios. Not only is the theme

catchy as heck — it actually has depth to it, something still very rarely

heard from Western games at the time (as opposed to Japan, where people like

Nobuo Uematsu had already been making waves since the late Eighties). The importance of the music for the

game’s atmosphere was clearly felt by the team, so much so that I usually

have to slightly lower the default volume at the start of the game —

otherwise, it can be hard to actually hear the characters talk over it. Other

than the main theme, heard only in the intro and, later on, at the climactic

ending of the game, the soundtrack is humble enough to recognize itself as a

soundtrack — consisting of generally inobtrusive, not highly dynamic looping

passages — but each track almost perfectly conveys and emphasizes the

atmosphere of each location. The St. George’s Books theme, for instance, is a

variation on the main theme, but played in a different, milder and lighter

tonality to indicate the location’s status as a more or less «safe space»

from the impending doom and gloom. Grandma Knight gets a relaxing, cozily

romantic theme to show that her little house is the place to just "take a load off" as she keeps

suggesting to her favorite Grandson ("your ONLY grandson, but nice try,

Gran!"). The Voodoo Museum theme, driven by frantic tribal percussion,

is all mystical, foggy, and wobbly, with an undercurrent of danger which you

cannot, however, adequately decipher as either a harmless shadow of the past

or an ominous portent of the future. The Police Station theme is based on a

slightly stuttering martial theme that is more comical than threatening,

quite well in line with Officer Frick’s donut belly — and so on. It is Holmes, probably, who bears chief

responsibility for not making the game all too New Orleanian in nature,

because practically none of the tracks bear any resemblance to the New

Orleanian traditions of jazz and R&B — other than the obligatory looping

bars of ‘Saints’ quietly resonating around Jackson Square. But this is, in a

way, inevitable, since most of our stereotypical ideas of New Orleanian music

revolve around partying and entertainment, while Gabriel Knight is not a game about

either. Grandma Knight might have had her childhood around the early Louis

Armstrong years, but having her blast ‘Heebie Jeebies’ around the house would

have produced the wrong feeling for the scene. And a little 18th century

Baroque-inspired theme for Madame Cazaunoux’s residence is certainly more

appropriate for her stiff and stern demeanour than, say, anything in the

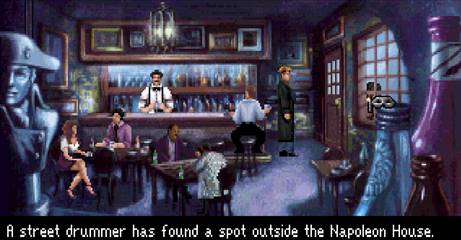

style of Professor Longhair. (I do have serious doubts, though, that even

such a poshly named bar in the French Quarter as the "Napoleon

House" could attract a lot of clients by continuously blasting the

melody of Vivaldi’s "Lute Concert In D" from its speakers — not

that there’s anything wrong with that). Still, as fine as the music is, I

repeat that it may well be necessary to tune it down a bit because, believe

me, you just do not want to miss the game’s single greatest attraction — the

voice cast. Apparently, like most other Sierra products at the time, the game

was released both on CD-ROM and on

floppy discs, without voice support, but I sincerely pity those who could not

afford a CD drive in those days and had to dish out money for the floppy disc

version. For all of Ken Williams’ documented original mistrust towards

Jensen, he did help her get the budget for Sierra’s first-ever all-star cast:

the game was not the studio’s first one to hire professional artists, but

certainly the first one to have artists of the level of Tim Curry and Mark

Hamill star in chief roles. The first and last

one, to be more precise: future games, both Sierra’s and non-Sierra’s, would

typically restrict themselves to voice actors par excellence, people like Dave Fennoy or Jennifer Hale who are

on much handier terms with the microphone than the camera. But at the time

when the first Gabriel Knight was

produced, there was some genuine excitement about interactive video games

merging with actual cinema and perhaps even replacing it (you can see that

excitement with your own eyes if you watch the accompanying Making of Gabriel Knight video, with

Jensen, Curry, and Hamill all hinting at the gorgeous future to come... which

never really came, of course) — which is why, I think, all these people at

that particular moment in time were so quick to agree to Sierra’s terms, even

if I cannot imagine them making a lot of money from it. Tim Curry as Gabriel Knight was, and

continues to be a divisive choice. For the role, he expectedly takes on what

he tries to pass for a genuine New Orleanian accent, a bit of a task for

someone raised in Plymouth, and even more of a task if one tries to infuse it

with «manly charm», sleaziness, cynicism, and hip snobbery and still come

across as a likeable character with whom the player might want to identify.

With the rise of modern sensitivity, it becomes even easier today to write him

off as «gross», «creepy» or whatever, but fuck modern sensitivity — as far as

I’m concerned, Curry did a great job with his performance. His Gabriel Knight

is rarely, if ever, directly offensive or rude: he does have a knack for

pranking his pal, Mosely (more because Mosely is a pompous ass than because

of his general personality disorder), but he is excessively polite around

people more knowledgeable than himself (like Dr. John at the Voodoo Museum or

Prof. Hartridge at Tulane University), kind and loving around Grandma Knight,

and romantically clichéd, but hardly «creepy» around his sudden love

interest, Malia Gedde. He is most certainly a guy of the I-take-what-I-want variety,

joking and provoking around boundaries — but never really overstepping them.

(Which is precisely why I am far more ambivalent about Curry’s reprisal of

the role in Gabriel Knight 3,

where, I believe, he did overstep

certain things, as well as overplayed certain others — but let us not get too

far ahead). The other great lead performance is by

Leah Remini as Grace, who, unfortunately, got to be played by three different

actors in three different games; Remini comes first in my book, though

(closely followed by Charity James in Gabriel

Knight 3 and distantly by Joanne Takahashi in 2). She is the perfect female counterpoint for Gabriel’s

manliness, as she fully matches him in sarcasm and cynicism where necessary,

but can show just as much sympathy and compassion — in fact, more sympathy and compassion, as she

constantly rebukes Gabriel for his pranks — when need arises. Remini creates

here the perfect image of a loyal, intelligent, too-wise-for-her-age sidekick

whose only reason for being a sidekick is a male-oriented market for video

games (and even that was going to change by the time of the second game). In

fact, she had been my ideal representative of womanly intelligence in

videogames for so long that I was all but horrified to discover her ties with

Scientology many years later (admittedly, though, she had been indoctrinated

by her family since childhood, and she did leave the organisation willingly

in 2013, subsequently dedicating a lot of effort to dismantle its web of lies

and corruption — good for her). The third and often unsung hero of Gabriel Knight’s voice acting is...

no, not Hamill (though his bumbling Detective Mosely will be a total blast

for anybody who only knows Mark as Luke Skywalker), and not even Michael Dorn

(whose Dr. John is so Worf-like in nature that it is quite impossible to

dislike the guy even when he proceeds to tear your heart out), but rather the

Narrator — a role which went to the then 68-year old black lady Virginia

Capers, a veteran of Broadway and TV shows who was presumably asked to

develop some sort of moody, creepy, Voodoo-flavored Caribbean accent for the

job. This she does, delivering all of her lines in a slurry, often barely

understandable drawl (non-native English speakers will have to turn on the subtitles, and probably at least some native

speakers as well) — typically sounding like a 100-year old witchdoctor

dictating her last will and testament from her dying bed; but believe you me,

no Narrator ever has managed to utter lines like "The windows are sealed

shut with old paint" or "The bookrack doesn’t open" with more

style and flair. Regardless of whether that accent is in any way «authentic»

or not, Capers is perhaps the one person most

responsible for setting the surreal and imposing atmosphere of the game. Honestly, though, I cannot think of

even a single example of downright bad acting here. Minor acting gems include

the gruffness-and-toughness of Jim Cummings as Officer Frick (still a long

way away from his most notable roles in BioWare games); the mystery-and-elegance

of Leilani Jones’ performance as Malia Gedde (it is amusing that she would

later go on to voice the much more cartoonish, but every bit as efficient

Voodoo Lady in the Monkey Island

series); and the perfect realization of the «insufferably haughty academic»

stereotype by Monte Markham as Prof. Hartridge (one of Markham’s very few

appearances in video games). "...And I am heterosexual [looking at Gabriel rather warily] —

when I practice sex at all [with a

nasal and rather condescending flair], which isn’t very often [quickly and with a small tinge of

embarrassment]" — classic, classic stuff. Given the sheer hugeness of the overall

volume of dialog, special kudos should go to Stuart M. Rosen, all of whose

previous experience was with TV animation, for directing the cast — most

likely, not an easy job with so much B-level talent in the studio. The effort

paid off dazzlingly well; and even if the voiceovers in the original game

predictably suffer from overcompression and general imperfections of voice-capturing

technologies circa 1993, the soundtrack still remains reason #1 why the 20th

Anniversary remake does not stand a ghost of a chance next to the original

game, sounding like a bored high school recital in comparison. And while

voice acting in video games has since then become a steady and respectable

profession, with many memorable performances and multiple stars accumulated

over the past 30 years, I can safely say that while some of the best games of

recent decades certainly match the level of emotion and classy theatricality

of Sins Of The Fathers, it is hard

to think of a game that would undeniably surpass it. |

||||

|

Being an unusual and

barrier-breaking game in so many respects, it would have been weird if Gabriel Knight did not introduce a few

notable changes to Sierra’s gameplay mechanics and graphic interface, as

well. The latter typically remains hidden during gameplay, with black empty

space left at the top of the screen to host it and similarly empty space left

at the bottom to host the subtitles (thus creating the impression of a

widescreen movie experience on a square TV screen); activating it with the

mouse reveals a stylish, stone-colored menu with a whoppin’ eight icons to turn your mouse in —

Walk, Look, Talk, Question, Take, Open, Use, and Move (for the record, a

typical Sierra point-and-click game at the time had about 4 obligatory

actions, plus, at most, 1 or 2 optional funny ones, like Space Quest’s Smell and Lick, or Larry’s legendary Unzip). From a pragmatic

standpoint, some of these are superfluous: for instance, you can open just

about any door by Using it rather than Opening it, and I can’t really

remember a single instance of the Move icon to have been uniquely relevant in

any useful way. (Talk and Question, however, do serve different functions,

since Talk is mostly about chit-chatting on minor subjects, while Question

opens up the Important Dialog screen with character close-ups). But from a

world-building perspective, they all make sense because Jensen, as she did in

King’s Quest VI, went to the

trouble of writing up various, often funny, reactions to Gabriel trying out

various actions on different objects and people. (E.g.: move Grace — "Move THAT wall of ice? Good luck!", open Grace — "I don’t even want

to think about what you mean", etc.). Given how jam-packed most of the

locations are with different hotspots for different objects, you can spend

quite a bit of time randomly poking around stuff in different ways — and

while 90% of these actions will not lead to any significant results, it may

be well worth it just to hear Virginia Capers make even more fun of you in

her mildly condescending Voodoo voice. Another unique option of the interface

is the Tape Recorder icon, by using which you can actually relisten to all of

the Important Dialog previously had with different characters. This is useful

if you want to refresh your memory, especially on all the tons of historical

and cultural information dropped on you by Dr. John, Prof. Hartridge, or

Magentia Moonbeam; but I sort of feel that it was mostly thrown in just

because Jane and Co. were so enthralled with the quality of their writing and

performing, they wanted to give you, the Player, the generous option of

relistening to all that great work whenever you felt like it, which,

according to the authors, would be all the time. I never really had to use

it, but it’s still nice to lug that Tape Recorder around as a souvenir (and

it sort of became a staple of the Gabriel Knight games from then on). Even moving around had become a little

different. In most Sierra games up to that time, you simply moved around from

one screen to another, perhaps fast-forwarding from one location to another

if you took a train or a plane; this often resulted in a lot of time-wasting

backtracking, or in getting lost if the map was too large and unwieldy. In

order to move through Gabriel Knight’s New Orleans, you simply leave your

current location and are taken to a map, where you pick your destination at

will (new destinations gradually open up as the game progresses). This, as I

have already mentioned, pretty much eliminates the chance at generating a

proper «New Orleans atmosphere» by having your character walk the bustling

streets, but it does get you very quickly to where you are going. (In Gabriel Knight 2, Jensen would adopt a

compromise where the basic principle was still the same, but you could at

least walk around the center of Munich, sucking in bits and pieces of German

life). The French Quarter map is, in its turn, integrated with the map of the

larger New Orleans area, and from there, if you so desire and when the time

comes, you can take the airplane to Munich. (Offbeat sidenote: one of the plot’s

most egregious slip-ups is the idea that, apparently, you can get from New

Orleans to Munich in less than one day and still have time left for

activities, even if you are actually

flying eastward. I cannot imagine that Jane Jensen could be so blatantly

ignorant of the structure of the space-time continuum, so I am just going to

have to assume that it was decided to keep things that way to keep the number

of overall days in the game to a nice roundish 10. We also do not bother all

that much with such boring issues as passports and visas — okay, maybe an

American in 1993 did not need a visa to fly to Germany, but surely he must

have needed one to fly to Benin). Most of the gameplay is centered around

the good old walk-talk-use mechanics, though there are also the

aforementioned puzzles with Voodoo codes and Rada drums which require a

slightly different approach (quite an intuitive one, though, no need to pull

out your manual or anything). As things begin to get tense and dangerous, the

game introduces situations which require quick reaction if you want to escape

almost certain death — as in many other Sierra games from that time, these

situations would later create a lot of trouble on faster-operating machines

(for instance, players found it nearly impossible to escape the animated

mummies in the African hounfour), but today playing the game in DOSBox with

lowered cycles niftily solves all the difficulties for you. Fortunately, Jane

Jensen has always been firmly in the camp of «no action sequences in

adventure games, period», so you won’t have to worry about getting your

Gabriel Knight to jump his way out of or shoot it through Voodoo ambushes. In the promotional video for the game,

Mark Hamill describes how he was amazed and befuddled by the choice-based

nature of the story, pointing out how difficult it is for a voice actor to

adapt to this type of Schrödinger’s Cat approach. This is actually

curious, since, compared to the typical RPG or even to the mode of adventure

game later popularized by TellTale, Gabriel

Knight does not offer much by way of choice: every once in a while,

Gabriel is capable of giving out

different answers to proposals from other characters, but this happens fairly

rarely, and most of the game is very straightforward. Each puzzle typically

has just one correct solution; you can solve them in different order, or you

can fail and try again, but ultimately Jensen railroads you into taking the

one and only correct path. You do not have a choice about whether you want to

fall in love with Malia Gedde (you do), about whether you want to become a

Shadowhunter (you are not sure, but you will anyway), or about whether you

want to fool a harmless old lady by impersonating a priest (you do, because,

to paraphrase Day Of The Tentacle,

"if you want to save the world, you have to relieve some old ladies of

their family jewels"). You do

have a choice of whether you want to return the police badge that you stole

from your old pal Mosely to impress your potential love interest of your own

free will, or be forcefully relieved of it by an enraged Mosely on the next

day — that much choice you do have.

And then there is the endgame, of course, where you can choose to try to make

peace with your arch-enemy (and survive) or to exact vengeance on it (and die

along) — but would you really want

to leave Grace standing on the balcony of St. George’s Books in the company

of Detective Mosely, in a Gabriel Knight-less world?.. Anyway, all I wanted

to say is that the game mechanics is not really designed for multiple choice

options, and that’s fine by me; it doesn’t make the experience any less

perfect. |

||||

|

In some ways, Gabriel Knight: Sins Of

The Fathers marked the highest point of the Silver Age of Adventure

Games, as I call it — that point when some people were ready to believe that

video games were about to become something much bigger than just video games,

just as some people believed around the age of Woodstock that popular music

was about to become something much bigger than just popular music. Both

parties turned out to be wrong, of course, but even if dreaming big almost

inevitably leads you to eventual disillusionment and depression, it also

often results in masterpieces which, even decades after, still have I AM SO

COOL BECAUSE THE PEOPLE WHO MADE ME DREAMT BIG written all over it in the

largest of letters. The 21st century would, of course, still see plenty of

ambitious videogame projects blowing people’s minds, from Half-Life 2

to Mass Effect to The Witcher 3 etc. etc., but it can be argued

that there was really no such time as that brief time window in the early

1990s, when technical improvements in digital video and audio led people to

think of their work in videogaming as potentially going beyond simply

«filling a niche» on the market. Talking specifically about Sins Of The

Fathers, there is just something about that game which elevates it well

above the status of «market-oriented product» and puts it into the category

of «trying to create an entirely new type of art», and, might I add, not

entirely failing in its task. That the future so subtly promised by the

game, and so unsubtly raved about in its promotional video, never really came

to pass is lamentable and most probably inevitable: neither Jane Jensen nor

anybody else in the business could find it in themselves to make the rivers

flow inwards, that is, to draw videogaming out of its niche and make it

replace TV or literature (even pulpy one) in the public conscience. This is

why, while subsequent generations of plot-based games kept improving in

technical terms — graphics, music, animations, gameplay, special effects,

overall length and size, etc. — few, if any, ever managed or even set out to

surpass the likes of Gabriel Knight in terms of character depth, plot

complexity, or literary quality of dialog: by all accounts, this would have

been a waste of time, since what was already there was quite enough for 95%

of consumers on the market — after all, nobody plays video games to find the

next War And Peace, right? Not that I am comparing Gabriel Knight

to War And Peace — far from it; for its time, it was simply a very

right step in a very right direction which could have, one fine day,

resulted in the universe of plot-based videogames producing its own War

And Peace. Instead, public disinterest and marketing strategies pretty

much halted that development, for which nobody can really be blamed. But

while many other games totally on the level with Sins Of The Fathers

have been produced since in many sub-genres, from pure adventure to action-adventure

to RPG, I still return to this one every once in a while just to experience

that rather singular jolt, to share the bottled excitement of a group of

people who felt they were working on something really, really special that

might, perhaps, one day change the world. It never did, but then again,

neither did War And Peace, and you certainly can’t blame Tolstoy for

not trying. |

||||