|

The Beast Within: A Gabriel Knight Mystery |

|

|||

|

Studio: |

Sierra

On-Line |

|||

|

Designer(s): |

Jane

Jensen |

|||

|

Part of series: |

Gabriel

Knight |

|||

|

Release: |

December 1995 |

|||

|

Main credits: |

Producer: Sabine Duvall Artists: Darlou Gams, Layne Gifford,

John Shroades Music: Robert Holmes |

|||

|

Useful links: |

Complete

playthrough (10 parts, 626 mins.) |

|||

|

What do you do when you

have just written and shipped the best adventure game of all time? If you are

Jane Jensen, you set your sights on making the second best adventure game of all time — and if you are the year

1995, you make your best to ensure that it will look and feel nothing like it

looked and felt back in the year 1993. It was a strange period, but,

fortunately for us all, things changed quickly enough for artists to be able

to offer surprising — if sometimes frustrating — new solutions before you

even had the time to wear out your trusty PC. Notably, by 1995 the gaming industry

had entered a new phase — full-motion video, or FMV for short, when digital

video and audio capacities had matured enough to allow for actual filmed

footage, with real backdrops and live actors, to be used for videogaming

purposes. For a few short years, FMV semi-successfully competed with the

other leading trend, 3D imaging, managing to hold its own largely because

early experiments with 3D looked so doggone awful. Once 3D graphics finally

began to improve, FMV lost out and died a quick death due to all the numerous

technical inconveniences accompanying filming and editing (let alone the fact

that few, if any, genuinely good actors ever let themselves be seduced into

joining that particular line of work). These days, even veteran players do

not hold that many fond memories of FMV titles from the early-to-mid-1990s

(remember Night Trap? no? good!);

but, as always, there are respectable exceptions to the rule. At the very

least, there are no theoretical

reasons for a FMV game not to be able to provide the required levels of

believability, player immersion, and entertainment; for the most part, they

failed for the same reason as so many early stages of other technological

breakthroughs, with people too overawed by the very fact of something so cool

made possible to take proper care of the handling and adaptation of said

breakthrough. Sierra’s own pioneering experience with

FMV was on Phantasmagoria, a

Roberta Williams game (of course!) which was undeniably «special» and went on

to become one of their best-selling titles, even if players today mostly

remember it for a good laugh and chuckle (somewhat unjustly, but this is no place to delve into another game’s

flaws and merits). However, Jensen’s project for a second Gabriel Knight

game, to be also done in FMV, was most certainly greenlit before, not

after Phantasmagoria hit the shelves, showing how much of a risk taker

Ken Williams was to allow two

seriously budget-draining processes run at the same time. In all honesty, I

do not know just how excited Jane was at the idea that her next game was to

be done with live actors rather than voice acting, but I guess if she weren’t

excited at all, she would be free to stick to the tried and true (like Space Quest or King’s Quest did). The «realistic» FMV setting inevitably led to

drastic changes in everything — script, dialog, puzzles, game mechanics — but

Sierra On-Line was never not about change, after all. Just as it happened with Phantasmagoria, The Beast Within bumped into numerous unpredictable issues, ran

over schedules, ran out of budget, had to be mostly filmed in California

instead of Germany, and ultimately featured far less content than Jane had

originally planned. Still, completed it was

before the end of 1995, just in time for the Christmas market, and although

it sold quite poorly compared to the heavily advertised and

«cheaper-thrilled» Phantasmagoria,

it quickly earned a far more benevolent critical reputation than Roberta

Williams’ competing brainchild. Unlike the first Gabriel Knight game, there was no specific hoopla about bringing

in a new era of interactive entertainment or anything like that — after Phantasmagoria, The Beast Within brought nothing specifically new to the table

other than the talent, enthusiasm, and hard-working attitude of its creator,

which seemingly made the title less «legendary» than Sins Of The Fathers. In some ways, however, Jensen’s sequel ended

up as an even more impactful and satisfying... if not «game», than at least

«experience» than its predecessor. At the very least, it is unquestionably

the last truly great product released by the original Sierra On-Line before

its shameful demise, and one of the

best designed and most, should I say, soulfully crafted sequels in adventure

game history, let alone the best FMV game ever created, and the one you

definitely need to take a look at before pronouncing sentence over the genre. |

||||

|

Content evaluation |

||||

|

Allow me to start out with

a bang — I do sincerely and honestly believe that The Beast Within: A Gabriel Knight Mystery tells the single best

story that I have ever had the fortune of encountering in a videogame. I have

not played them all, so I am not insisting on objectivity; and I am also well

aware that, technically, Jensen’s plot is far from being consistent, has

quite a few holes (some of which, as I shall try to show below, are downright

annoying), and rests on a fair number of philosophical and artistic

clichés that would be unforgivable, were this a work of literary fiction

(which is why, by the way, I would not recommend you any of Jane’s attempts

to tell the story of Gabriel Knight in the actual form of printed novels —

yes, I did try reading both Sins Of The Fathers and The Beast Within, and the reasons why

both have been out of print for decades become quite obvious by the fifth or

sixth page or so). Absolutely none of it matters, though,

when what you are really dealing with is a computer adventure game. What

Jensen did here was take everything that made Sins Of The Fathers so good — the suspense, the mystery and

intrigue, the masterful weaving of historical fact and modern fantasy — and

made it even better by directly entangling the mystery into the life and fate

of our protagonist. Unlike so many other fantasy tales, The Beast Within is not concerned about you saving the universe

from imminent destruction; it is more concerned about saving yourself from the delicious jaws of

temptation, as well as making one formerly lost soul, with which you might

have quite a bit in common, find redemption. Avoiding black and white colors,

confusing expectations at every turn, and providing you with quite a few free

history lessons as a bonus (although you must be careful so as not to confuse

true history with make-believe), the game almost gets away with becoming a

complex morality tale at least on the level of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, even as its genre conventions

do not properly allow it to aim at anywhere higher in the canon (and, of

course, the language of Jensen’s dialogue is quite far removed from the

exquisite complexity of the Victorian Age). One can only imagine how good it

would get without the limitations of an FMV production back in its day. The story itself now takes place in

Germany rather New Orleans — incidentally, a somewhat more suitable setting

for Jensen, who actually lived in the country for a while (conversely, she’d

never been to New Orleans prior to writing Sins). Apparently, after having solved the Voodoo Murders case

and solved his financial problems by writing a bestselling novel about it,

Gabriel Knight has relocated to his ancient family nest in the small Bavarian

town of Rittersberg, where he would rather just soak up the atmosphere and

prepare for his next bout of writing than to actually step into the ancestral

shoes of the Schattenjäger,

battling supernatural evil around the globe. However, as tragedy conveniently

strikes on the outskirts of a nearby national park, Gabriel finds himself

pulled into solving yet another murder mystery — involving unnaturally large

wolves, a zoo superintendent with some weird philosophical views on life, an

exclusive hunting lodge in the City of Munich, a bunch of rich and perverted

aristocratic playboys, and, of course, Gabriel’s family history. Meanwhile, Gabriel’s trusty assistant Grace

Nakimura, sick and tired of being holed up at St. George’s Books in New

Orleans, packs up her suitcase and travels to rejoin Gabriel in Rittersberg —

only to find out that he’d just left for Munich to assist in the

investigation, and that nobody in Rittersberg is willing to tell her his

exact location, presumably out of fear that if they do find each other, it

will be hard for Jane Jensen to keep the player in control of just one

character. Yes, the game actually lets you — forces you, that is — to play as both Gabriel and Grace, shifting action between one

and the other in the form of discrete chapters, and at least as a plot

device, this is certainly an improvement on the first game, where Grace was

always in control of book research for Gabriel’s tasks, but all of that took

place firmly behind the screen. Now, for the first time ever, you actually do the book and museum research, as

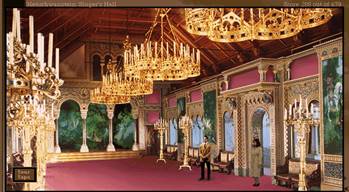

Grace, while Gabe takes care of more mundane stuff. So far, so good — the regular murder

mystery with the usual suspects. Where this show really strikes gold is

closer to mid-game, when it slowly becomes clear that recent events may be

tightly linked to century-old events that involve perfectly historical

characters, namely, the Mad King Ludwig of Bavaria (1845–1886) and his good

friend, Richard Wagner. Without getting all spoilerish in this matter, let me

just reiterate that no other game I have played has ever succeeded in

building up such a masterful mystification, intertwining stone cold

historical facts with pure fantasy (and just

a little bit of cheeky tweaking, such as substituting the real paintings at

Neuschwanstein Castle with ones that are relevant to the story). Yet it is

also a mystification that somehow makes perfect sense, showing a deep

understanding of the complex personality of King Ludwig without cheapening it

through the addition of a supernatural element to his life story. By the end

of the game, you are all but ready to believe that things really happened the

way Jensen made them happen — how come they keep all this fascinating stuff

away from us in those boring history books? Considering that the plot involves at

least three distinct time layers — an 18th century werewolf incident, the

19th century Ludwig story, and the 20th century murder investigation in

Munich — and that all three lines are tied together by a complex bunch of

werewolf lore, some of it authentic and some added in by Jane for story

purposes, it is almost a wonder that it does not all fall apart at the end.

The videogame format does allow the writer to easily get away with holes and

inconsistencies: for instance, the game ultimately agrees with the lore piece

which states that an «Alpha Werewolf» can only be killed by a «Beta Werewolf»

and does exactly so at the end — yet this actually goes against the original plan which certainly did not include the

element of the Beta killing the Alpha, despite both Grace and Gabriel having

had the opportunity to read up on their werewolf lore multiple times. Or, for

that matter, the ridiculously easy-to-find locations for all the acts of the

Lost Wagner Opera (yes, that’s a big thing in this game) which, of course,

should have all been swept clean by the caretakers and repairmen at

Neuschwanstein over the past 100 years. However, I shall chalk all these and

other blunders up to the serious deficiency of resources on Jane’s part — it

is well known that a lot of content had to be cut from the final version of

the game for lack of time and money, and so let us simply pretend that in an

ideal world, where Ken Williams could get her another couple million dollars

and reschedule the release for 1996, The

Beast Within would be tighter than a submarine’s hatch. The one part of the plot that maybe does not work quite as well as

it should have is the romantic line between Grace and Gabriel. In the first

game, whatever tender feelings may have existed between the two principal

characters were buried deep behind several layers of sarcasm and

trash-talking (besides, Gabriel was too busy chasing another girl to pay much attention to his feelings for his

assistant). In The Beast Within,

due to the general plot construction, most of the trash-talking is relegated

to letters which the two star-crossed smarty-pants exchange between each

other on a regular basis (another plot blunder — apparently, mail moves at

the speed of sound in the Gabriel

Knight universe); otherwise, it is quite clear that Grace now has such

strong feelings for Gabriel that they not only make her lose her cool all the

time, but actually get her in big trouble with everybody who, according to

her, is trying to keep her away from the big lout (particularly Gerde, his

German housemaid and assistant, whom Grace suspects of unruly romance with

her employer just because, well, she is a female employed by a male). This might not be such a big problem

for those who never played the first game, but it creates the impression of a

rather huge and unwarranted personality change for those who have — and give

Grace, who is more or less supposed to represent the pinnacle of female

intelligence, an aura of extra bitchiness more befitting of some capricious

pop diva. On the other hand, this sudden streak of renegade behavior is at

least in agreement with Gabriel’s own feelings toward his partner — a mix of

suppressed admiration, deeply hidden longing, and open fear, if not terror,

at her presence. All of this could

have been handled better, particularly in the final act when the two finally

meet, albeit under rather restrictive circumstances; but Jane Jensen is just

so much better at writing detective and historical dialog than romantic one

that perhaps it is a good thing that the two quasi-lovebirds are given so

little time together. Still, I would certainly take half a

dozen romantic conversations between Grace and Gabriel over Jensen’s totally

superfluous introduction of Mr. and Mrs. Smith, a couple of «demonologists»

from «Miramak, Pennsylvania» (apparently there is no such place, but if there

were, I’m absolutely sure that it would be the best place in the world to

grow up as a demonologist). With her obligatory deck of Tarot cards, fortune-telling

clichés, and soap-opera American optimism, Mrs. Smith is barely half a

step over the ridiculously cartoonish figure of Harriet from Phantasmagoria, so much that I’ve

always suspected she was secretly written into the script by Roberta

Williams. Apparently, her main function in the story is to somehow try and

melt the ice congealed around poor Gracie’s heart, tear down her wall of

sarcasm, and make her acknowledge that the world is not always ruled by cold

logic and reasoning — which is all fine and dandy, as long as she had been

provided with dialog of at least Golden

Girls quality, rather than Santa

Barbara. So much for the bad stuff — but on the

positive side, the game script is filled with colorful characters, from

Grace’s cheerful German helpers (a music student dreaming of becoming the

next Furtwängler and a romantic historian obsessed with decoding the

enigma of King Ludwig) to Gabriel’s snobby aristocratic partners at the hunt

club, made to look as nasty and disgusting as possible, but each in his

special way. And, of course, top care is taken to make the primary

antagonist, Baron Friedrich von Glower, as thoroughly sympathetic as a

fictional villain can get. The homoerotic undertones between Gabriel and the

Baron are written out subtly, and although they are definitely present

(which, of course, led to inevitable criticism on grounds of associations

between homosexualism and evil), the game concentrates far more on issues of

loneliness and companionship than it does on carnal aspects — again, not a

particularly new topic in the post-Anne Rice era of literary fiction, but

quite a fresh one in the era of computer gaming. Jensen’s von Glower is the

single most complex (and likable) villain in video games up to 1995, and I am

actually not sure that a more

complex villain has truly appeared in the medium since then. The story offered by Jensen is

completely straightforward, without any branching paths or even minor choices

to make along the way, which is a bit of a pity — especially since at the end

of the game, Gabriel is explicitly offered an important choice, yet it is not

really ours to make, and with so much of the game luring and tempting you to

join the dark side, not being able to take that step (even if it leads you to

an officially «bad» ending) feels disappointing; that said, it would have

taken a lot of extra courage for

Jane to throw in such a path, and I hardly have the right to judge her for

railroading us into a happy ending. (Or maybe she thought that it would be

excruciatingly humiliating, after all, to have a mighty Shadow Hunter end his

career as a werewolf — and a lowly Beta

werewolf at that). For sure, a million small and not so

small things could have been done to tighten up the plot, introduce even more

depth and nuance, sharpen up the humor, deepen the dread, and make the game

even more realistic and immersive. (At the peak of my passion for the game, I

remember fighting insomnia by thinking of all the things I would have done

differently for both Sins Of The

Fathers and The Beast Within).

But even the fact that Jane Jensen was able to pull the whole thing off,

warts and all, exactly the way it is, is an astounding, groundbreaking

achievement in merging together new technologies, mass market appeal, and some good old-fashioned

scholarship and literary etiquette. |

||||

|

Perhaps the single worst

impact that FMV games had on the adventure genre was in the sphere of said

genre’s main attribute — puzzle design. In the good old days of the

point-and-click universe, you typically solved puzzles by putting things on

top of other things, er, I mean, clicking stuff on top of other stuff. Pick

up everything that is not nailed down, combine it with everything else, and

sooner or later you will get your solution — that is, after you have explored

multiple incorrect pathways. With FMV, each of these incorrect pathways would

require separate filming — it is one thing to simply program in an option in

which you are doing something wrong, but quite another to require actors

before a blue screen to act it out. (Could you imagine a filmed Day Of The Tentacle in which each of

the three leading actors would be required to sprinkle invisible ink over every other actor?) Subsequently, it is hardly

surprising that most of the FMV-style adventure games rank among the easiest

adventure games ever — The Beast Within

hardly being an exception.

Unless you are intentionally being a complete oaf, missing easily detectable

hotspots right and left and forgetting your map layout as soon as you move

from one location to another, beating the game is barely a challenge at all.

Most of the actions you have to take are fairly simple and logical, solved in

one or two steps, and clearly hinted at by the game itself. I recall only one

specific puzzle that could have anybody stumped — at one point in the game,

you have to fool a not particularly bright doorman by imitating the sound of

a door knock with the help of a concealed cuckoo clock, which really requires thinking out of the

box (more annoyingly, it requires noticing that a formerly closed clock shop

is now open without any evident difference in appearance). But at least it is

a somewhat elegant and non-trivial solution, as compared to the triviality of

most other actions. To compensate at least somewhat for

this simplicity, Jane adopted several controversial decisions. First, the

game requires you to do your research — a lot

of research, particularly when you are playing as Grace. At one point, you

have to visit two of Ludwig’s castles, Neuschwanstein and Herrenchiemsee

(«Here-at-chemistry», as Gabriel calls it), and action simply will not move

forward until you have taken a close look at just about every single exhibit — after which, as a reward, you will be

offered one more trip to the Wagner museum in Bayreuth, where, guess what?

yes, you guessed right. Actually, although I have seen many

people complain about that necessity, I have no problem with it. Jane Jensen

games always come with educational value, and if you do not want to be

educated, go play Super Mario Bros.

or whatever, you lowly pleb. The real

Grace Nakimura would certainly not have missed any of that info, so why

should you be allowed to slack off? What bothers me more is that diligent

exploration, in such situations, comes across as a substitute for actual puzzles rather than being complementary. In

the end, the most complicated intellectual tasks offered to poor Grace are to

pick a bunch of flowers to make peace with her nemesis Gerde, and to think of

a way to carry a pigeon inside Neuschwanstein (for which purpose you shall

actually need a whoppin’ two

different objects). The other decision is to include a

couple of «special» brain teasers, one of which is somewhat similar to the

Rada drum challenge in the first game — you shall have to splice different

tape recordings of the voice of the zoo’s administrator in order to compose a

message to his subordinate. This you will find either very fun or very

tedious, but at least there are some vague hints that Gabriel can give out to

help you work out the basic syntax of this message. Another unusual challenge

comes at the very end of the game, when you have to chase the bad guy into a

specific position inside the large basement of the opera theater by sniffing

him out and closing doors in specific order before you run out of time and

the bad guy escapes. Again, this is not too difficult, and will hardly

require more than 2–3 tries even from a geometrically challenged player like

myself, but the challenge is somewhat unexpected and anticlimactic, coming

right after the mind-blowing, super-tense opera scene. In a game like Broken Sword, which is all about

solving those sorts of puzzles, it would have looked natural; in a Gabriel Knight game, you will most

likely feel relief rather than proud satisfaction upon completing it. In any case, the one impression of The Beast Within you most certainly

won’t be walking away with is that of a «puzzler». Most of the actual

detective and deductive work will be done by the game for you; all you actually have to do is just bump around,

gathering evidence. From this point of view, what we have here is even far

less of an actual «game» than Sins Of

The Fathers, more like an immersive multimedia experience with occasional

chokepoints at which you are expected to commit some minimal brain work. But

that’s just the typical FMV experience for you, and who knows how it would

have turned out otherwise? Gabriel

Knight 3, for instance, has unquestionably stronger puzzles, yet that

emphasis on solving the mysteries on your own comes at the expense of a truly

great plot — apparently, there is just no way you can have that cake and eat

it too. |

||||

|

I shall try to keep this

section relatively short, because Sierra’s FMV adventure games tend to

produce most of their impact during cutscenes — the actual «movie» parts of

the game where the player’s impact is completely non-existent, and all the

thrills are to be gotten through acting and sound. In between the cutscenes,

however, you are extremely limited in your actions and even in your feelings:

this, I am afraid to say, is one bit where The Beast Within loses out to Phantasmagoria,

which, for all its flaws, at least made you feel nervous and stay on your

toes all the time while exploring the mansion. The main problem is that

the game, whenever it is actually functioning in «game mode», is extremely

static. It is impossible to freely move Gabriel or Grace around the screen;

you can only push them right or left in pre-designated directions, or induce

them to examine a hotspot. Promenading through the streets of Rittersberg, or

across the squares of Munich, or over the dense forests of Bavaria, is a bit

like marching in circles inside a prison courtyard. You do get a tiny bit of

entertainment every once in a while — some animated figures near Munich’s

Town Hall sit around a fountain playing "When The Saints Go Marching

In" (an ironic nod from Sins Of

The Fathers), and the guards at Neuschwanstein keep changing positions at

regular intervals, but on the whole, the action going on around you is

minimal. (One can only guess just how populated the game might have been,

were it released in the age of The

Witcher 3!). Still, the atmosphere does

change, and change it does, when shit hits the fan properly and the game

moves into the danger zone. As in the first installment, Jane takes her sweet

time to build up the sense of danger — throughout the first four chapters of

the game, Gabriel and Grace both experience uncomfortable premonitions, but ultimately

manage to stay in the safe zone. However, by the end of the fifth chapter the

beautiful and peaceful forest in which our hero is merely supposed to do a

bit of hunting becomes a death trap at night — and it is at this moment that

the game completely shifts its tone, as the mystery-solving quest becomes a

quest for your own survival and sanity. All I can say is that this is a much harsher atmospheric twist than

the one in Sins Of The Fathers,

where the tone of the game also changed at about the same point, but the

feeling of danger was never as sharply pronounced. After all, in Sins Of The Fathers the worst that

could happen to our protagonist was mere death; in The Beast Within, death is less scary than damnation, and it is

difficult for even the most jaded and least impressionable person in the

world to not feel anything about poor Gabriel’s fate. On the other hand, humor is

not such a well integrated feature here as it was in Sins — which is partly due to the lack of Tim Curry (who would

probably have a thing or two to improve about the script), and partly to the

fact that Jane clearly wanted to come up with something deeper and darker

than she did first time around. Sins

were populated from top to bottom with characters acting as comic relief, from

Officer Frick to colorful patrons of the Napoleon House to good old Detective

Mosely himself; Beast has no comic

characters at all (unless you count the Smiths, which you shouldn’t), and

even if Gabriel has not completely

lost his sense of humor, he is no longer operating on the top tier level of

the sarcastic son-of-a-bitch he was in Sins

(it would be up to Tim Curry to restore him back to that position in the

third game in the series). Some might find this a good thing, others might be

disappointed; I know I was one of the others when I first played the game,

missing the light touch of Sins and

all the personality changes in both Grace and Gabriel — eventually, though, I

got used to that, and even justified it by the obvious trauma that the

characters went through at the end of Sins

(I mean, Gabriel did lose the love

of his life at the end of it; even the most sarcastic son of a bitch could

want to cut down a bit on the puns and innuendos after that). |

||||

|

Technical features |

||||

|

It is tricky to discuss the

technical aspects of FMV games separately from each other — considering, for

instance, that they are built upon actual acting by real people, which means

that visuals and sound are integrated far more tightly than usually.

Consequently, here and elsewhere in reviews of Sierra’s FMV titles I am going

to expand the traditional «Graphics» section to cover acting in general,

while the «Sound» section will be reserved exclusively for the musical

soundtrack (which, in the case of The

Beast Within, most certainly deserves its own section). All of the action in The Beast Within takes place in two

modes: (a) cutscenes, in which actors are filmed properly, either talking to

each other or carrying out various actions, against actual backdrops or, far

more commonly, against green screen backgrounds later substituted by still

backdrops; (b) interactive scenes, in which you can direct your character

across the screen, usually against a still photo as a backdrop. Since all the

video files for the game had to be gruesomely compressed in order to fit into

one package (it still took about 6 CDs to get it together), quality of images

in cutscenes is predictably much lower than in interactive scenes — admiring

the beauty of the game is really only possible with still images, not moving

pictures. The still images are beautiful, though, especially

considering that this time around, the game crew actually took a trip to

Germany in order to film the necessary locations — such as the Marienplatz in

Munich, or the Neuschwanstein Castle of King Ludwig. It goes without saying

that if you are unable to be there in person, you are much better off with

high resolution images than stock footage from a 25-year old videogame, but

that, of course, is not the point, not even any more so than the alleged

«cheesiness» of Neuschwanstein (Ludwig’s «fairy tale» castle, so sweet and

rococo-ish that even Disney appropriated it for Sleeping Beauty). The point

is that the locations do add a

serious touch of authenticity to the experience — so serious, in fact, that The Beast Within ends up being one of

the very, very few FMV games that really makes you lament the quick,

decisive, and irreversible demise of the genre. It is also impressive just

how well the fictional elements are integrated into the real images,

reflecting the same delicate interweaving of reality and imagination in

Jensen’s writing. I have already mentioned the fictional «wolf panels» at

Neuschwanstein, replacing the original paintings, but it is also fun how the

fictional locations in Munich — the office of Gabriel’s lawyer and the hunt

club, in particular — are smoothly inserted to the left and to the right of

the Town Hall building (so smoothly, in fact, that when I actually visited

Munich, I half-expected to see the hunt club after turning the corner). And

something tells me that not a few fans of the game who visited Neuschwanstein

afterwards probably spent a bit of time poking around pre-designated corners,

trying to find out whether those secret caches for the three acts of the lost

Wagner opera really existed... Still, unless you are a

super-serious sucker for German historicism of the late 19th century, you

shall probably spend more of your time on the various cutscenes than on

admiring the still scenery. Thus, it is time to talk about the cast — for

which, unfortunately, it was impossible to assemble such a strong list of

B-tier players as it was for Sins Of

The Fathers, either due to limited budget or because good actors tended

to be very wary about lending not only their voices, but also their

appearances to this strange new format. Apparently, there was some talk about Tim Curry possibly

reprising his role, but Jensen vetoed this herself, claiming that Tim’s looks

are not quite what she had in mind for Gabriel Knight. (On which I

respectfully disagree, because, after all, the voice is hardly just randomly

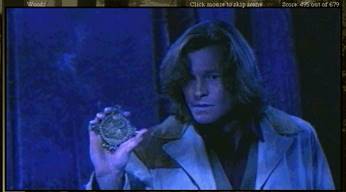

tied to the face, but whatever). In the place of Tim Curry

comes Dean Erickson, a bit player in various TV shows who actually hoped that

his starring role as Gabriel could be his big break, but eventually went on

to found an investment advisory firm (in more recent photos, he looks more

like Gabriel’s lawyer in Munich than Gabriel himself). Either all by himself

or as directed by director Will Binder, he introduces a huge personality

shift to Gabriel — this character is clearly less cocky, less blatantly

self-confident, is no total stranger to shyness and humility, and generally

reserves his sarcasm for snobs and assholes who really deserve it rather than

spewing it around 24/7 with no signs of discrimination. His badboyishness is

now more like a nostalgic badge which he can still proudly wave around if

required ("do you like women, Herr Knight?", he is asked at one

point in the game by a particularly sleazy member of the club, to which he

half-cockily, half-embarrassedly replies, "I’ve been known to..."),

but overall, it’s as if the events of the first game really knocked him down

a peg or two. This means that you will

most probably either hate Erickson’s performance next to Curry’s, or love it

— it would be difficult to experience comparatively strong emotions for both,

and it would be impossible not to be affected by their differences.

Personally, I remember a sharp original pang of disappointment, not because I

disliked Erickson’s Knight per se, but more because this was one of those

Sean-Connery-to-Roger-Moore types of transitions where you find it hard to

accept that the same fictional character has just received a personality

reboot for no apparent reason. Over time, though, I learned to appreciate the

rather fine nuances of Erickson’s acting: the mimics, the gestures, the

well-placed theatrical pauses, that thin aura of negligence and sloppiness

combined with streetwise intelligence, even the major tantrum which he throws

at Grace as the curse begins to affect him — all of that is pretty well done,

want it or not. If he’d only spent less time twitching his lips or running

his hands through his hair in the cutscenes... but I guess that is more the

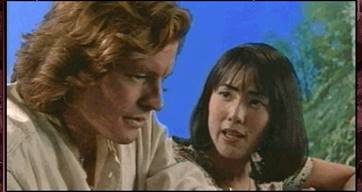

fault of the director and the FMV format than anything else. Joanne Takahashi, as Grace,

usually gets more flack for her acting, but honestly, I don’t think she does

a bad job, either. In the first game, Leah Remini’s Grace was a mostly quiet,

reserved, sarcastic fountain of wisdom, which she preferred to dispense from

behind her desk rather than hopping from place to place or getting herself

involved in much of anything. In The

Beast Within, her role is more active, as we have to deal with her not

only in the capacity of researcher and investigator, but also in that of a

jealous lover (at the beginning) and a brave and caring rescuer (at the end).

If there is a single flaw in her performance, it is probably that she takes

the role too seriously, and tends

to overact every time the script requires a strong emotion — her hysterical

reaction to Gerde in Chapter 2, for instance, would only look convincing if

there were a long and transparent story of deep emotional traumas leading up

to it (it is a bit hard to believe that Gabriel’s leaving New Orleans for

Rittersberg was really the only thing to cause our lady to jump off her

rocker). But other than that she’s as fine as can be — she is

Japanese-American, she is intelligent, she is beautiful, she is well-spoken

and sharp-mouthed, and she is adorably clumsy in every single bit of romantic

scenery (some might think of this as a negative, but I suppose that a

character like Grace Nakimura would

be quite clumsy and uncomfortable about romance in real life anyway). That said, I think everybody

and their grandma would agree that the single best bit of acting in the game

is delivered by the Polish actor Peter Lucas as Baron Friedrich von Glower.

Why that guy never made it big time (I think his biggest break would later be

a supporting role in David Lynch’s Inland

Empire, a movie that nobody remembers any longer anyway) is a total

mystery to me — chalk it up to the mysterious lottery of fortune, ever once

in a while liable to supporting mediocrities like George Clooney or Jon Hamm

(sorry, guys) over actual talent. Lucas’ von Glower is, simply put, the single greatest villain in video

game history, at least in terms of how elegant, intelligent, multi-sided,

caring, and overall sympathetic you can make a guy who has also made it his

life’s purpose to destroy the lives of people he actually cares about. He

steals every single scene in which he is present — fortunately, there are

quite a few of them — and there is something hypnotic about his voice even in

a lengthy sequence where you just read a letter explaining his plans and

motives. If only he were given higher quality dialog — if only the lead

writer for the project had been, say, Herman Hesse instead of Jane Jensen —

the scenes in von Glower’s residence, where he explains his «philosophy» to

Gabriel, would have been totally iconic... though I guess that they are still iconic in some ways, at least as

far as FMV gamemaking is concerned. In addition to this (insufficient, but

still respectable) layer of intellectual depth, he is also able to portray

some good old-fashioned homoerotic attraction that comes across as elegant

and courteous rather than sleazy, cheesy, or riddled with over-the-top

clichés of writers and actors who try a bit too hard — an advantage of

the game for which Jensen and Lucas have to share the honors. On the whole, I am

surprised to say that conspiculously and unquestionably proverbial «bad

acting» is all but lacking in the game. Even the horrendous Mrs. Smith,

played by veteran TV actor Judith Drake, is acted out quite credibly — she is

just an utterly annoying character, written in by Jensen because she probably

wanted to show all the mysterious ways in which God sends us help from above

(sometimes it even comes in the shape of an annoyingly super-sweet provincial

lady who can’t keep her mouth shut for a second), and she plays the part

precisely like an annoying character should. Nicholas Worth is an imposing

and hilarious Kommissar Leber (the obligatory big dumb detective who

alternately helps and hinders the protagonist); Richard Raynesford does a

convincingly all-out nasty Baron Von Zell; and charming old gentleman Kay

Kuter (whom players will probably more commonly recognize as the voice of

Griswold Goodsoup from Curse Of Monkey

Island) plays a wonderful Werner Huber, the owner of the Rittersberg inn

and the Herald of Doom for both Gabriel and Grace (you haven’t lived, really,

until you saw and heard him make that grimace and intone

"WE-E-E-E-REWOLF!" in a voice seemingly carved from the Rock of

Ages). In short, if you do want

Proverbial Bad Acting, go play Phantasmagoria

— next to that one, all these guys deserve their Oscars. In terms of actual

cinematography, the capacity of the game is understandably limited — there is

not that much you can actually do against a green screen — but it is

impossible not to mention the climactic opera scene at the end, for which

Sierra really went all-out, hiring

real opera singers and putting on quite a grand theatrical show, with

excellent editing work and tension build-up quite worthy of a Hitchcock production

(or at least a Francis Ford Coppola, though I think Hitchcock is clearly a

bigger inspiration for Jensen). It is the single most outstanding moment in

all of Sierra On-Line’s cinematography — and, probably, the highest point of the entire FMV era as well, the likes of

which we have not seen ever since and most likely never will again, which is

a pity (grand cinematographic spectacle in 3D animation is quite common these

days, but still, it can never truly replace the same spectacle put up by real

people of flesh and blood). One can only speculate how

much better it would all have turned out if the game had been produced at

least 5–6 years later than it was. The resolution of the videos is

horrendously low, necessitating total compression and interlacing (at least

there now exists a patch that helps you de-interlace the videos, making them

a bit more watchable on modern screens); the green screen impediment means

that the characters’ contours are crudely and unnaturally sticking out

against the backdrops, reducing immersion; and the few elements of CGI

integrated with real video capture — such as the werewolves in the last

chapters — look much too cartoonish and clumsy when contrasted with actors,

which really takes away from the intended feel of horror (especially today,

of course, but even in 1995 the difference in quality was clearly visible).

Not everybody was willing to look past these technical deficiencies back in

1995, and, clearly, very few people will be willing to do that 25 years

later. But just as we now marvel at, for instance, the skills of the artists

who could at one time record the entirety of Sgt. Pepper on 4-track tape machines, so might we actually feel

inspired by the work of the people who could make a generally believable

experience of hunting werewolves in the cities and forests of Bavaria by

putting a bunch of unknown actors in front of a blank screen. |

||||

|

By 1995, Robert Holmes, who had

composed the original soundtrack to Sins Of The Fathers as well as acted

as the game’s producer, was not just a composer, but also Jane Jensen’s

husband, and so there was clearly no way that he would not be responsible for

the score to the second game as well — and thank God for that. If the game was going to feel less than

a traditional game and more like an interactive movie, with big fat emphasis

on the movie part, that also meant

that its soundtrack would have to feel more like an actual movie soundtrack —

with strong, memorable themes going beyond mere background accompaniment.

After all, when we’re dealing with an actual adventure game, you usually do

not want the music to be overbearing and overwhelming, because sooner or

later you are going to get stuck in some specific environment, and wrecking

your brain over puzzle solutions with loud, expressive, dynamic music

intruding inside your busy space will eventually become torture and probably

lead you to turning the sound off altogether. But if at least half of your

gaming time is going to be filled up with watching cutscenes, that is a whole different thing

altogether: it means that making music into an integral part of that

experience is an obligation, and that music better be worth it. Whether Holmes would be able to pull it

off was not evident from the beginning, precisely because the scale

difference between the soundtracks to Sins

and Beast was like the difference

between, let’s say, an album of surf-rock instrumentals and an Andrew Lloyd

Webber-type rock opera. However, right from the opening themes of the

Prologue and the opening chapter we may be reassured that the man is fully up

to the task. Despite all of the music being MIDI-synthesized (real

orchestration surely would have been nice, but BUDGET BUDGET BUDGET), Holmes

succeeds in getting the required epic effect over and over again, largely

taking his cues from the symphonic rock of the 1970s, I’d say — I can

definitely hear echoes of Pete Townshend’s keyboard work on Quadrophenia in some of the tracks,

among other, sometimes less flattering, things (such as American arena-rock à la Journey). To prop up the continuity effect,

Holmes borrows and reworks quite a few of the older themes from Sins, such as the main Gabriel Knight

theme, or the Police Station theme (which, appropriately, is now playing at

specific intervals inside the German

police station, with an appropriately more brutal percussion sound). However,

all of them are intensified, and Holmes’ trademark piano riffs are bashed out

with all the force he can give them. The piano, in general, is the most

important instrument here, intermittently churning out epic, depressing, or

romantic moods depending on the situation; one exception is a frantic «Danger

Theme», which typically bursts out of nowhere to scare the shit out of you

whenever it is necessary — for instance, during Grace’s nightmare sequence,

or during a pivotal moment when Gabriel stumbles upon the gruesome evidence

inside the werewolf lair. The sequencing arrangements are also interesting —

thus, while the music within cutscenes is always rigidly scripted, outside of

them the themes for specific locations do not loop around continuously, but

rather crop up, play out, and fade away with intervals of silence between

them, presumably to prevent you from getting irritated by constant sonic

accompaniment if, for some reason, you tarry too long in one place (which is

never really the right thing to do). Holmes’ biggest challenge for the game,

of course, was to come up with at least a brief snippet of the Lost Wagner

Opera — the key element binding the 19th century segment of the story to the

present time. Any lesser mortal would have cowered at the challenge, but a

big strong woman like Jane Jensen certainly would not have married a

spineless wimp unable to beat Herr Richard at his own game, and so Robert

actually sat down and composed a 10-minute piece (with Jane providing the

libretto), performed in full during the climactic Transformation scene in the

last act. Of course, it does not really sound much like Wagner (not least

because Wagner himself had relatively little experience working with a MIDI

interface), but there is something Wagnerian

about it all the same — like the impressive whirlpool of strings during the

ominous Minstrel Dance, somewhat reminiscent of Wagner’s proto-minimalist

moments (such as the Rheingold overture);

most importantly, it gets the job done, slowly and masterfully deepening the

colors until the explosive revelation. (As a sidenote, I would like to remark

that the whole story of The Beast

Within and specifically the dark supernatural tones of it, crossed with

the idea of damnation and salvation, is actually much closer in spirit to von

Weber’s Der Freischütz, whose

romanticism was a direct predecessor to Wagner — unfortunately, «a lost Weber

opera» would neither have fitted in with the Ludwig/Wagner narrative nor

sounded as impressively for the average player. I would not be surprised to

learn that Holmes was more influenced by Weber than Wagner, though). Regardless of these details, it is

clear that the soundtrack to The Beast

Within was one of the most ambitious sonic undertakings in at least

Western videogame history up to that point — and even if you lack the ability

or desire to test it out within the game itself, I still recommend

experiencing at least two

or three themes in order to grasp the overall seriousness of the entire

project. It is actually quite befuddling to me that, despite showing such

major progress here, Holmes was not picked up by any major movie or videogame

studios ever since — then again, it is also perfectly possible that he is

just a simple, modest, unambitious, stay-at-home soul, perfectly content to

restrict himself to writing soundtracks for his spouse’s games for ever and

ever since, God bless the both of them. |

||||

|

And this is where we come

to the last and, conversely, least impressive part of the game — the

interaction part. As long as you watch

the game, it is relentlessly great, but, as we have already seen in the Puzzles section, as soon as it comes to

actually proving your own worth, it

begins to disappoint. The interface of the game generally follows the new

pattern introduced with King’s Quest

VII: still images and video cutscenes occupy about 2/3rds of the screen,

the rest of it being given over to the menu bar which is... surprisingly

empty (apparently, the middle chunk was supposed to be given over to

subtitles, but ultimately the game shipped without them — there is a fan-made

patch that actually adds English subtitles, though). You really only have a

small inventory window out there, as well as your trusty tape recorder which

allows you to relisten to important conversations (a feature carried over

from Sins Of The Fathers) and a

video replay option which allows you to rewatch some important scenes (not

all, though). At least you can freely save and restore your games at and from

every location — thankfully, Jane dispensed with the utterly stupid «bookmark

progress» alternative of King’s Quest

VII and Phantasmagoria. On the

other hand, the division of the game into several chapters introduced in the

same games works very well for The

Beast Within, both agreeing with the same division (into «days») of Sins Of The Fathers and allowing us to

alternate between Gabriel and Grace on a chapter-by-chapter level. Unfortunately, one thing

Jane could not dispense with is the utterly minimalistic point-and-click

interface, which forces you to helplessly wave your dick, uh, I mean, cursor

around the screen until it reaches an otherwise unidentified hotspot and changes

into a dagger, at which point you click on it to either get a verbal

description or interact with it. The lack of different options means, for

instance, that sometimes in order to achieve progress, you have to first click on an object to get its verbal

description, and then click on it again

to interact with it and actually get somewhere. This is annoying and stupid,

and I am pretty sure Jane (with her very nice set of alternate cursors in the

first game) must have hated it, but such were Sierra’s laws of the time —

what has been predetermined by the next generation of Roberta Williams games,

goes for everybody else’s games as well. Still, the game quickly

lulls you into being totally assured that as long as you stick out your

tongue, roll your eyes, and click your cursor / dagger all over the screen,

the game will just keep on rolling — all you gotta do is reach out for those

sweet little hotspots. This is why the very last puzzle in the game, when you

actually have to get just a wee bit trickier with your dagger in order to

solve the issue of the Beast once and for all, turns out to be so frustrating

for a lot of players (I actually surveyed several «blind playthroughs» on

YouTube to make sure of that) — because it requires of you to take a type of

action that was never required or even hinted at in the game before. (Bad

game design! Bad game design!) Other than that, the

interface is user-friendly: you can easily skip any cutscene you wish by

simply clicking the mouse (comes in handy if you’re a speedrunner, I guess),

you can watch your progress in points at the top of the screen, and oh, I

almost forgot to mention that Grace actually keeps a journal in the same spot

where Gabriel has his tape recorder — in which she regularly takes notes,

ordered by subject and chronology, and

can actually read them aloud to you (along with plenty of sarcastic comments

on Gabriel and just about all of her new acquaintances). The journal part is

nice to have, though not essential (well, perhaps

essential for those with short memory spans — there is, after all, quite an

overload of information to be had from completing Grace’s parts of the story),

and I think that it is pretty much the only innovative aspect of the entire

interface. Keeping journals (though not always voiced ones) would later

become a fairly regular feature in adventure games (e.g. The Longest Journey or Syberia),

but I am not sure just how widespread the practice was by 1995. (Certainly

some of Sierra’s mystery games, such as the Laura Bow series, could have benefited from it early on, but

Roberta was apparently fine with a «dummy» journal for her heroine). Finally, just like in the

first game, you won’t be able to die at all in the first four chapters (and

you can’t die as Grace at all), but

eventually there comes a time when you may

die, and later still, a time when you will

die with 99.99% certainty, many times over before you figure out what to do.

For such cases, there will be a «Try Again» option, so there is no need to

continually save and restore (you might want to do just that while running

around the basement in wolf form, though, to save you lots of ennui). |

||||

|

Like the first Gabriel Knight game, the

second one also sets the bar way higher than it could ever hope to reach. It

is not truly a game as such; it is riddled with technical deficiencies which

are hard to overlook or forgive; its plot is full of holes; even the best of

its characters often speak in clichés and truisms; it may easily be

deemed as too insulting for the intelligence of people who read books, yet

too confusing and boring for those who do not. In a certain way, its fate is

oddly similar to the fictional fate of its most interesting character — no,

not Gabriel Knight, of course, but rather King Ludwig II of Bavaria, whose

human flaws were many and whose artistic tastes were debatable, but who has

managed to remain a fascinating figure all the same. Of course, big and sprawling ambitions are

not always welcome — they have resulted in way too many embarrassing

JRPGs over the past half century, and in the world of videogames, where flash

is so commonly prioritized over substance, they can easily do more harm than

good in any setting. But in Jane Jensen’s case, what really helped was

focusing the story on personal levels, making it more of an exploration of

the conflicting inner selves of 20th century Gabriel and his 19th century

mirror Ludwig — an exploration which can admittedly get soapy at times, but

hits you pretty hard in the feels at others (can I admit that I actually

teared up at the final scene of Gabriel and Grace on the bridge? no? too

late). Then, even when you stop and think and begin to be tempted to laugh at

your emotional reflexes, even from a cold intellectual point of view you

cannot deny that the integration of the werewolf story with the historical

narrative of Ludwig and Wagner is one of the most brilliant ideas in the

history of mixing together fact and fiction. So it was realized less

efficiently than it could have been... but who can tell, really? It’s not as

if there were precedents for this in gaming history, right? I do believe that if you have at least

certain faint feelings for (a) adventure gaming, (b) European history, and

(c) folklore-based fantasy — all three of these, that is — your life will be

somewhat incomplete until you have played this game. If you are totally

indifferent toward at least one of these points, that statement should

be retracted (thus, pure history buffs will most likely scoff at the werewolf

angle, and pure fantasy fans will probably fall asleep during Grace’s

never-ending tour of Bavarian museums). But if you are lucky enough to be

interested in all three, The Beast Within: A Gabriel Knight Mystery

will most assuredly work its magic even today. Hopefully, some day a grateful

bunch of fans will use the necessary AI to bring the video files up to modern

standards; until then, we’ll just have to curb our expectations for the

reward of a unique experience which, in some ways, has never been bettered —

even if the arrival of modern standards has seemingly set up all the

necessary conditions for making it artistically obsolete. Which, as of 2020,

it most certainly is not. |

||||