|

Gold Rush! |

|

|||

|

Studio: |

Sierra

On-Line |

|||

|

Designer(s): |

Ken

& Doug MacNeill |

|||

|

Part of series: |

[stand-alone title] |

|||

|

Release: |

1988 |

|||

|

Main credits: |

Programmers: Ken MacNeill Music: Anita Scott |

|||

|

Useful links: |

Complete

playthrough (322 mins.) |

|||

|

Basic Overview

In a general sense, already the very first King’s Quest that put Sierra on the map was «edutainment» — it

introduced you to the world of classic, time-honored fairy tales in which you were an active character yourself;

so much more fun, apparently, than just reading the books. Still, in its

essence the King’s Quest series

was not so much about education as it was about overcoming the limits of

Roberta Williams’ artistic fantasy: unable to come up with a fantasy universe

of her own, she instead relied on the tried and true to achieve her goals.

Subsequent series could all be said to contain a certain amount of

educational value — Space Quest

taught you some rudiments of science fiction, Police Quest trained you to be a cop, and Leisure Suit Larry, er, uhm, well, you know... — but Sierra yet

had to design an actual title that could lay a proper claim to being able to

replace an actual school textbook for the player, while at the same time not

losing the advantages of involvement, excitement, and basic fun delivered by

a computer game. Enter brothers Ken and Doug MacNeill, two experienced Sierra

employees who had proven their worth to the company as early as the original King’s Quest (Ken was in charge of

programming, Doug was working as a graphic artist) but so far had no credits

for actual game design behind their belts. Information on how exactly they

got the idea about making a game based on 19th century American history, and

how they managed to sell it to Ken Williams, is not easy to come by: Williams

does not even mention the game in his book, and the MacNeills pretty much

seem to have vanished off the surface of this Earth after shipping the title

— apparently, soon afterwards they left not just Sierra, but the digital

industries altogether. Which is a bit surprising, given the exceptionally

warm reaction received by Gold Rush!

upon its original release. Perhaps (I also have no information here) it was a

commercial disappointment, but in any case it certainly did not stop Sierra

from further delving in the «edutainment» department. The brothers chose the California gold rush of 1848 as the

game’s main theme, which gave the studio a tremendous challenge: come up with

a vaguely credible simulation of mid-19th century America, contrasting its

urbanized environments with the Great Wilderness without embarrassing

themselves too much over the pitifully limited capacity of the AGI engine.

With any previous Sierra title, you could always work around any encountered

obstacle by bending and twisting your imaginary universe whichever way you’d

like, but the challenge set here was to ensure close-to-100% historical,

cultural, and stylistic accuracy; to that effect, the game was even

accompanied with a special edition of the small 1980 paperback California Gold: Story Of The Rush To

Riches (by Phyllis and Lou Zauner), more a collection of (not always

verified) historical anecdotes about the Gold Rush than a serious study but

still certainly a more useful and detailed source than any regular school

textbook — and also, as it happens, an excellent way of ensuring copy

protection, so the player had absolutely no choice but to open it on a new

page every time he/she booted up the game. Exactly how well-balanced history, entertainment, and playing

mechanics turned out to be is something we shall try to figure out in the

main body of this review, but, as I said, contemporary assessments were

largely positive, and as far as I can tell, veteran Sierra fans still have

fond memories of the game, for various reasons. Gold Rush! even boasts the dubious honor of being the only

classic Sierra game the rights to which have managed to be salvaged from the

Vivendi / Activision / Microsoft mafia, due to Ken Williams’ benevolent

decision to donate the ownership back to the MacNeill brothers upon their

leaving Sierra — only for them to resell them later to little-known German

developer Sunlight Games, who apparently released a remake of the game in

2014 and then made a sequel in 2017; however, both of these were panned by

fans and I am sure they had good reason to (I’ll return to this for the

conclusion). Still, it’s quite a telling bit of trivia: after all these

years, the game is still remembered with fondness by people who may even be

willing to pay for an up-to-speed modernization. |

||||

|

Content evaluation |

||||

|

Plotline Unlike the classic Oregon

Trail which Gold Rush! was

obviously inspired by, Sierra’s product is not a «strategy» title, but a

proper adventure game where you generally get by through solving puzzles —

and which, like any adventure game, must have an actual plot based around

specific game characters for the puzzles to be inserted within. Thus, the

MacNeill brothers came up with the idea of Jerrod Wilson, an everyday

newspaperman from Brooklyn who, like so many of his peers in 1848, gets

caught up in the prospect of going to California to make his fortune. The

only additional angle here, making Jerrod a tiny bit more special, is his

complicated family history, including the mysterious fate of his long-lost

brother Jake — who, throughout the game, acts as the unseen guiding hand to

his younger sibling. Even

so, the addition of the «looking for one’s lost brother» motif is merely a

common trope like any other: on the whole, Jerrod Wilson is there only to

give you a tiny glint of individuality. Even by the standards of Sierra’s

earliest games, he comes across as easily the least memorable of all of the

studio’s protagonists (well, maybe King Graham of Daventry can offer some

competition, but he at least has the justification of having been the first

on the scene — meanwhile, Jerrod Wilson already had to compete with

characters as colorful as Roger Wilco and Leisure Suit Larry). Fortunately,

the game is really not about the family troubles of a colorless Brooklyn

newspaperman; it is about setting the Brooklyn newspaperman in the middle of

a global chain of events. For the most part, all you have to do is follow the

generic scenario that is already vividly described in California Gold: the Average Joe, disillusioned with his dreams

of making it big in the city, reads about the discovery of gold in California

— the Average Joe sells off his property to buy a ticket to Sacramento — the

Average Joe reaches his destination by land or by sea, braving whatever

natural or human obstacles there are along the way — the Average Joe procures

his equipment, claims a stake, grows a beard, and eventually finds his

fortune. (Well, in the latter case the game does offer a helpful shortcut: if

you do not want to spend a lifetime looking for fortune, it always helps to

have a mysterious long-lost brother to find it for you). The

good news is that this is a case of life indeed being more exciting than

fiction: all the MacNeills had to do was stick to the conventional historical

narrative (admittedly, somewhat embellished by folklore) and lo and behold,

the game is nowhere near as boring as might seem natural for a game with, at

best, the tiniest sliver of an original plot. Throughout, Jerrod passes

through tons and tons of «ordinary» situations (for 1848) that look anything but ordinary out of the comfort zone

of the late 20th (let alone early 21st) century, and the sheer quantity and

diversity of these situations — which the MacNeills try to get you to tackle

as realistically as possible in the context of an early PC adventure game — ensures

that «boredom», apart from an occasional bit of grind here and there (more on

that in the next section), is not a concept that will frequently spring to

mind while you’re busy playing. Arguably

the best remembered thing about Gold

Rush! is the decision that Jerrod would be able to use three different

routes to get from New York to Sacramento — a land route (by means of an

ox-driven cart), a lengthy sea route (across Cape Horn), or a shorter sea

route interrupted by a foot trip through the Panama Isthmus, the exact same

choice that real people had to make back in 1848. This threeway split was

quite a novel idea, heavily exploited by the studio («three games in one!»)

and actually implemented much earlier than the Team / Wits / Fists paths in Indiana Jones And The Fate Of Atlantis,

which usually get all the praise from retro-reviewers. In both cases, the

«three games in one» marketing slogan was a bit of an exaggeration, since the

lengthy initial and final chunks of the game would be essentially the same;

however, the middle parts are indeed completely different, adding a ton of

replay value, for the first time in Sierra history. Moreover, this cannot

even be called a gimmick — the three-path mechanics is there simply to

provide even more historical accuracy. Historical

accuracy is, in fact, probably the only key to properly assess the quality of

the plot, and, predictably, it only falters in those areas of the game that

have to do with puzzle-solving; e.g. (spoiler

alert!) discovering that you have to go through a toilet hole to reach a

secret gold mine sure makes for a great head-scratching conundrum, but

something tells me that this was probably not

how it used to be in 1848, even if you desperately needed to conceal a mining

paradise from the jealous eyes of prying neighbor seekers. Overall, though,

this is not much of a problem, and occasional puzzle-related absurdities are

well compensated by the ability to simply walk around, poke your nose into

everything, and get frequent (but not too lengthy) updates on the various

elements of American landscape, culture, and everyday life in the mid-19th

century. The

game becomes especially text-heavy during the course of Jerrod’s journey to

Sacramento, with both the land and sea routes heavily peppered with

enlivening details (e.g. "The food

on board is not as bad as expected... The usual fare is hard-baked biscuit,

salted beef, and boiled pudding once a week. Very few get sick from eating

them"), but the MacNeills clearly take care about the game’s pacing:

stretches when control is wrestled from your hands, with the game unrolling

on its own, are well interspersed with mini-quests that usually require you

to extricate yourself and your companions out of the next hurdle

(thunderstorms, famine, impassable areas, etc.), with education and

entertainment mixed in generally comparable doses. Modern

players with rigidly progressive mindsets will, of course, cringe somewhat at

how the game completely bypasses or bungles historically sensitive issues —

such as the fact that «natives» in the storyline feature merely as one more

natural disaster to be brushed off (there is actually only one hostile

encounter with them in the Panama jungle, with the dialog limited to

something like, "The lead native

on the shore yells, ‘Hungo bungo,

kram a zumba!’") — but it would be incredibly naïve to expect a

PC game from 1988 to do full historical justice in such situations.

Thankfully, they are very few: while the game certainly does focus on the

plight of the white American male, it never (well, almost never, if you forget about that native encounter) attempts

to culturally elevate him above anybody else (admittedly, by means of

omission). Nor does the plot really try to offer any serious morals or

judgements; all the story tells to you is a stern «this is how the people

used to live and act back then», and it does so credibly, even if I’m sure

that history professors will easily spot hundreds of minor inaccuracies (some

of them probably inherited already from the authors of California Gold). Indeed,

I appreciate how, on very rare occasions, the MacNeills are even able to slip

in bits of genuine drama. If you take the long sea route through Cape Horn,

for instance, you are introduced to the companionship of Eric, a young man

like yourself, first presented as an intelligent, healthy, happy, and

aspiring fortune-seeker, but then beginning to become eaten up by some

unnamed illness (T.B.? malaria? leukemia? nobody really knows). He gets

progressively worse as the journey continues, until one day you simply do not

see him any more — without a single word of explanation from the game.

(Apparently, if you think of the proper command — "find Eric" — the game just brushes you off with a laconic

"Eric was buried at sea").

This

is one of those situations where the laconicity of the game, technically due

to the general brevity of Sierra titles at the dawn of the PC age,

subconsciously turns into a grim and shocking artistic twist; I remember

being quite seriously disturbed by the wordless disappearance of Eric even when

I first played Gold Rush! in the

1990s. (Though I think I remember being aggravated by the ignominious death

of the little piggie, the ship’s mascot, even more — the poor guy does not

even end up saving the passengers from starvation, but actually gets spoiled

and ends up quite pathetically as fish bait.) Unfortunately, the same kind of

dramatic tension could not be applied by the MacNeills to Jerrod’s own family

history. Overall,

though, it goes without saying that Gold

Rush! is hardly an exercise in imaginative storytelling; for the most

part, the «plot» is just a series of diligent illustrations to the vividly

exaggerated depictions from California

Gold. No big surprise here — in 1988, Sierra adventure games in general

did not yet place much emphasis on thrill, suspense, and unpredictability.

Much more important for them was to bring your brain to boiling with

frustrating puzzles, while at the same time soothing it with seductive

environment — so let us see how the game fares on both of these fronts. |

||||

|

Puzzles The very fact itself that Gold

Rush!, unlike any previous Sierra title, was based on stern (if,

inevitably, somewhat skewed) historical reality set a special challenge for

the designers — where the classic idea of an adventure game puzzle was close

to «anything goes», with the

fantasy settings of the imaginary universes allowing for any kind of twisted

or absurdist logic, puzzles in Gold

Rush! had to be as realistic as possible. I mean, if you set your game in

New York around 1848 where your character needs funding for his trip to

California, you can hardly expect the player to deduce that the money is to

be found in the form of gold bars hidden in a tree hollow in the cemetery

that you can reach by luring an eagle with a leg of lamb and making him carry

you right to the tree top. You can,

however, read the book and learn that people used to sell their property

before heading out West, so that should give you the right idea. Unfortunately, realism in adventure games comes with a price

tag: most of the genuinely realistic puzzles are just... simple. When your character has to behave more or less like he

would behave in real life, and especially if you are also aided by a detailed

manual on life in the mid-19th century, beating the game becomes a fairly

simple challenge. And if you know a thing or two about the general Adventure

Gamers’ Code — «leave no stone unturned», «pick up everything that is not

nailed down», that sort of stuff — then it hardly even begins to be a

challenge. Going over all the situations from which poor Jerrod has to

extricate himself, I can hardly remember any where I would have to waste

hours on a solution, other than, perhaps, an occasional conflict or two with

the usual rough-hewn early Sierra text parser. Nor do I remember any

particular elegance to these challenges — no textbook examples on how to

concoct the perfect adventure game puzzle in this game. One

aspect of the game’s realism that was always highly questionable is its

reliance on random events. In order to stress just how much depended on pure

luck, the MacNeills implemented a bunch of situations where Jerrod could

simply die due to factors totally beyond your control — like your ship

running into an iceberg, or Jerrod himself catching some deadly disease and

giving up the ghost (what made things even more confusing is that some diseases were inevitable, but

curable if you prepared for the situation in advance, but others were random and

uncontrollable). As a reminder of just how fickle Mother Fortune can be,

these little programming pitfalls were probably effective, but they also

threw the fun factor out the window, and quite likely made not a few players

rage-quit the game, vowing to never pick up another Sierra title again. But

think about it from today’s perspective — how many games are out there where

your character can just... randomly

drop dead at any given point? As the Reverend Gary Davis predicted decades

earlier, death don’t have no mercy in

this game. Another

side of Gold Rush!’s realism is

the heavy use of realtime strategies: this was not the first time for Sierra

to rely on actual passing of time (King’s

Quest III already set the bar high enough), but in Gold Rush!, you find yourself constantly working against the

clock — particularly in the Brooklyn part of the game, where you have to

figure out what is going on and get yourself a nice ticket to the West Coast before the Gold Rush is officially

announced, causing a sharp decline in property value and closing off the sea

routes. Later on, there will be all kinds of deadly situations that require

quick responses, again, potentially causing quite a bit of nervous distress,

although this is fairly typical of most Sierra games. Finally, to dispense

with the realistic approach once and for all, let us also mention a couple of

very annoying «grinding» moments when you simply have to perform the same

digging operation over and over again to find all the required gold to let

you buy your supplies or receive the full amount of experience points.

Realistic? It might seem so, on one hand. But on the other, I seriously doubt

that Californian treasure-seekers would blindly pan their gold-carrying sand

at any random spot down the

Sacramento River; there must have been some

clues at least — clues that would have required much more effort to

incorporate in the game, so instead you just have to shuffle around the

screen like an idiot, poking your shovel or your gold pan around and praying

for mercy to your soulless random number generator. All

of this only serves to prove the old adage about realism and fun being

two opposite ends of the same pole — something that game designers in 1989

had not yet perfectly figured out. (Then again, most people in the world

still think of Indiana Jones as the most famous archaeologist in the discipline’s

history). The approach chosen by the MacNeills must have been quite

impressive to a lot of people back then — a small step toward making one

genuinely relive history through the miracles of the digital age — but it

kind of goes without saying that the degree of such realism as achieved in,

say, Red Dead Redemption 2 sweeps

the achievements of Gold Rush! out

the window. I can see how it could be possible to lure a modern young player

into the webs of an archaic King’s

Quest or Space Quest, but Gold Rush! will inevitably feel too

sloggy, too grindy, and too patience-trying even if you are a fan of American

history-themed games. On the other hand, at least most of those challenges

make sense and are not there just

to frustrate the player, as they are in Codename:

Iceman; anybody who is well used to the mechanics of old school adventure

games (and always remembers the hygiene of proper save-scumming) will find

them easy to bypass. The only challenges that are genuinely tough are those that have to do with the game’s meager, unsatisfying original «plot», a.k.a. Jerrod’s search for his long-lost brother Jake. In order to «facilitate» his discovery, Jake plants a series of clues for Jerrod whose absurd sophistication is better fit for an Indiana Jones environment than any realistic setting in mid-19th century America. One minute you are thinking like an actual person, selling your property and buying vital supplies for your journey — the next minute you are engaging in a most bizarre activity over your parents’ tombstone, or exchanging messages over pigeon post, or entrusting your fate to an unusually well-trained mule. Essentially, everything plot-related that the MacNeills have not picked out of California Gold, but rather extracted from their own brains is arranged in a series of puzzles to solve which you must completely abandon «real world logic» and entrust yourself to «adventure game logic» — which would not be a crime if this whole game were a Monkey Island, but having to constantly switch between the realistic and the absurd may seriously overwork your neurons. And even if you do get used to the pattern, the back-and-forth switching still threatens to break the immersion — which is, I guess, a pretty good excuse to stop complaining about the puzzles and start talking about the game’s atmospheric qualities. |

||||

|

Atmosphere

For

the standards of 1989, it must have worked pretty well. As the game opens,

you, as Jerrod Wilson, are standing atop a little canal bridge in Brooklyn

Heights, overlooking several lively streets with people walking, gulls

flying, and massive horse-driven carriages rolling around — with the (still

relatively low, of course) Manhattan skyline stretching across the water.

This must have been a sharp contrast for players accustomed to beginning

their Sierra game with a solitary character standing inside a lonely room or

on a landscape screen with nothing but waves crashing upon the beach or

something like that. Gold Rush!

clearly made use of hardware advances, taxing graphic processing power more

heavily than its predecessors, but by late 1989, they could allow themselves

to be generous, and it almost worked: Brooklyn Heights as depicted by the

MacNeills was one of the liveliest places in PC gaming up to that date. Naturally,

the limitations of the simulation become just as immediately obvious:

Brooklyn Heights consist of, at most, about 10 screens worth of exploration,

and most of the people you encounter are randomly moving mannequins with, at

best, 2-3 stock phrases each if you try to initiate conversation (much like

in any other Sierra game; but then again, is it really that different from «advanced» epic RPGs like The Witcher, where the atmosphere of

surrounding hustle-and-bustle is created much the same way, as random NPCs

keep spinning the same yarn over and over?). But still, what a difference: in

King’s Quest, NPCs felt like

purposeless alien dummies whose only purpose for existence was to advance

your plot. These guys, on the other hand, couldn’t care less about your plot

— but they feel like actual townspeople running around their business, even if you only see them running around and

never see them actually taking care of their business. (For this little

important touch, we still had to wait until Revolution Software’s Lure Of The Temptress four years

later). The

atmospheric bliss of Jerrod’s journey to California, regardless of the path,

is not that well pronounced because all three paths are quite linear, without

any pretense to an «open-world» environment, and the journeys themselves are

relatively short and laconic. But the contrast between the «civilization» of

Brooklyn and the «wilderness» of the surroundings of Sutter’s Fort is quite

well executed — the NPCs now have a much more rugged appearance (even Jerrod

himself begins to sport a rough beard) and are generally more aggressive

while protecting their turf, which, in itself, feels far more desolate and

dangerous than the «cozy» Brooklyn environment. A somewhat questionable

decision on the part of the designers, though, was to suddenly have much of

the narrator dialog appear onscreen with a mock-Southern accent ("That hammerin’ fool can’t hear ya over the

poundin’ of his hammer!") — surely they are not implying that a New

Yorker’s speech pattern and personality somehow underwent a serious mutation

overnight right after setting foot on the West Coast. In

any case, whatever compliments I might squeeze out of myself in relation to

the game’s immersiveness and realism, and no matter how much I superficially

admire all the hard work that went into the graphic, animated, and verbal

recreation of the era, there is only so much one could do in 1988 with the

limited capacities of the AGI engine. And in such situations, old games

exploring fantasy and sci-fi thematics are actually at an advantage, unlike

«realistic» games whose feeble attempts at creating a replica of the real

world inevitably pale as technology makes them obsolete — precisely the fate

of Gold Rush!, which, as I already

mentioned earlier, can only come across as a museum curiosity next to the

immersion level achieved by the likes of Red

Dead Redemption (if we’re talking old-timey America). |

||||

|

Technical features |

||||

|

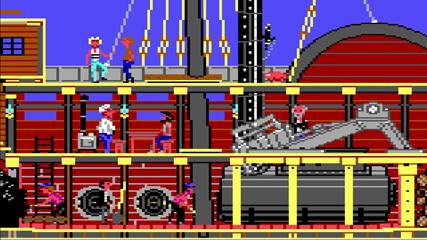

Graphics

Gold Rush! was one of the last, if

not the last, Sierra games to be

created within the AGI engine, allowing for 160x200 pixel resolution, and as

far as I know, there were no attempts to port it to the much-improved SCI

(320x200); however, by 1988 the studio had accumulated so much experience in

putting every single pixel to good use that you can easily assess the amount

of extra sophistication as compared to early titles in the King’s Quest or Space Quest series. This time around, every inch seems to be

brimming with detail: paved roads, tiled floors, dotted horizon lines, store

shelves packed with merchandise, and a measly three-screen long steamship

with each tiny compartment stocked with passengers, crew members, and / or

machinery, so much so that you can get a little sense of both the camaraderie

and the claustrophobia that must

have ruled supreme over the course of the journey. That

said, there is hardly anything specific that would stand out about the

graphics of Gold Rush! —

essentially, it is just a typical AGI-era Sierra game, albeit more

professionally crafted than earlier ones. Every once in a while, Doug

MacNeill does go the extra mile to add tension, such as in his portrayal of

the thunderstorm on the seaward journey (the rock-gray skies in combination

with the snow-white icebergs and the shaking screen are mildly terrifying even

today), but on the whole, I find it hard to list any particularly memorable

creations. Typically of the time, there are almost no close-ups in the game,

except for the opening screens, so that «artistry» is essentially limited to

backdrop illustrations. Of the walkin’-talkin’ sprites, the only historically

notable detail is the decision to include two variants of Jerrod: a smaller

one for the outdoor sequences and a much larger one for the indoor ones — a

technique that would become common in Sierra’s SCI-era games, starting with King’s Quest IV, but I think that Gold Rush! is the only (and thus, the first) AGI-era title that

openly employs it. Of course, it’s not just «NPC inflation» — everything is

bigger indoors, with a nice zooming perspective that creates a strong

contrast between the vast outdoors and the cozy (or claustrophobic) indoor

space, which can sometimes add a note of psychological comfort — though, to

be honest, outside of Jerrod’s journeys most of the outdoor space is not all

that dangerous. Honestly though, I’m just digressing here with nothing to

say, so let’s move on. |

||||

|

Sound Alas, in no other respect does Gold Rush! suffer more from the age of its release than in the

sound department. A game set in the America of 1848 literally begs for an appropriate soundtrack of

old-timey folk and country-western tunes — which certainly could not be

properly provided by means of the bleepy PC speaker. In the end, all you get

is a reasonable facsimile of ‘Oh! Susanna’ as the title tune — quite appropriate,

of course, as the tune’s original publication year is usually given as 1848,

and it became somewhat of an anthem for the «Forty-Niners» — and maybe, at

best, snippets of two or three other melodies scattered throughout the game,

most notably a looped verse of ‘La Cucaracha’ accompanying your ship’s

arrival at and departure from Rio de Janeiro (in a rather hilarious case of

both mistaken cultural identity and chronological anachronism at the same

time, but let’s not judge the MacNeills too harshly — they must have already

sweated out pints of blood while digesting all the information in California Gold, and the book did not

have enough space to teach the reader to distinguish Hispanic musical culture

from Portuguese). Other than that, there are minimal occasional sound effects

(very annoying in the PC speaker version if you do not install the patch to

convert them to MIDI — particularly in the sequence where you have to follow

your mule to your brother’s hideout and the machine vomits out a shrill and

repetitive musical phrase on every next screen) and A LOT of total silence,

even compared to other contemporary Sierra games in the AGI engine. Whoever

was «Anita Scott», credited for «music» in the game (this is her only credit

in the entire history of video games or any other medium), she certainly did

not do a very good job — for all the simplicity of the pre-sound card era,

games like Leisure Suit Larry and Space Quest could already be

populated with fun, catchy jingles, which is far from the case here. It also

kind of forms the impression that the only musical tune the American people

knew in 1848 was ‘Oh! Susanna’ (played alternately at full or half-speed),

and that it was always played on

any particularly joyful occasion. Anyway, one can only wonder about how

strongly the game’s atmosphere could have been boosted had it only been

delayed by one year (with the coming of King’s

Quest IV and MIDI synthesizers). |

||||

|

Interface

The only atypical element in the game menu was the «Elapsed

Time» option that allowed you to watch the chronology of your progress —

since the game allegedly took place in pseudo-real time, this made sense,

though, if I am not mistaken, the only time in the entire game where this really mattered was the opening

sequence in Brooklyn, where, if you tarried too long, the Gold Rush would be

officially announced and you would have to take a serious financial fall.

After choosing your route, however, you are pretty much free to take things

at your own pace, except for a bunch of obvious timed situations where you

have to take quick action before something dreadful happens. Speaking of dreadful, one good thing about Gold Rush! is that it is nearly 100%-free of any action sequences

— in fact, other than moving around and typing commands, I think the only

time when you have to do something else is the punctured-card puzzle at the

cemetery, and that’s not much of an action sequence. There’s even a bare

minimum of fall-down-the-ladder situations — plenty of ways to die in the

game, but very few of them have to do with the clumsiness of your fingers,

which is always a plus in Sierra games. (Some might argue that falling off a

ladder is still more reasonable than dying due to sheer bad luck — see above

on the factor of random death in the game — but since save-scumming is the

default way to go in just about any Sierra game, this won’t be too much of an

issue for the seasoned Sierra

player). |

||||

|

Verdict: Historical realism undermined by

technological (and inspirational) limitations. It goes without saying

that Gold Rush! is far from my

first choice when it comes to recommending old school adventure games trying

to simulate historical or mythological reality. Less than two years after its

release, Christy Marx would be showing the world how such a task should really be handled — and in terms of

combining educational value with sheer fun, even such a poorly remembered

piece of work as Pepper’s Adventures

In Time (1993) would be vastly superior. But let us give credit where

credit is due: Gold Rush! was

Sierra’s very first try at a slice of «virtual historic reality», and if they

tried it a little too early — not to mention, arguably, not putting their

best creative talents at the helm of the project — well, they still earn

points for going where no one had gone before without a safety net. Admittedly, it is

difficult today to properly appreciate the monumentality of this project —

not unless you play and assess the game in the context of all the other

Sierra stuff released around the same time. Most of the games took place

inside a relatively small, compact environment, with no hints of a veritable

Odyssey taking you from one American coast to another, let alone the idea of

having three completely different routes to choose from. In the soon-to-come

SCI era of Sierra, adventures that take you from civilization to wild nature

and back again would become standard fare, but in a way, they all looked back

to Gold Rush! as the original

pattern to take lessons from (both positive and negative). It takes a while

to visualize the game’s influence in your mind, but once you get the picture,

denying this influence becomes nigh impossible. And yet I hate

describing old video games as pure museum pieces, incapable of providing

entertainment and emotion after a certain period of time has elapsed — and

from this point of view, Gold Rush!

really pales even in comparison with the earliest King’s Quest or Police

Quest games. Alas, the MacNeills were unable to give the game what every

adventure title needs the most — and no, I am not talking about challenging

puzzles, I’m talking about personality.

With so much effort invested into building up a believable historical

simulation, the designers totally forgot about — or had no strength left for

— bringing their actual characters to life. Predating stuff like Red Dead Redemption by decades, Gold Rush! could have been a nice

psychological portrayal of its epoch, yet only a few tiny strands of plot

(like Eric and his tragic fate on the seaward journey) ever try to head in

that direction. (For comparison, The

Colonel’s Bequest, released but one year later, made a much stronger

attempt to immerse us into the lives and troubles of American people in the

1920s — although, admittedly, it was

a Roberta Williams game, and that always meant a much bigger budget on

Sierra’s part). In routine terms, this

is translated to the simple fact that replaying the game for the purposes of

this review was not a very fun experience for me. Even setting aside the

frustrating «realistic» random deaths, the gold-panning grinding, the mazes,

the unchallenging puzzles, the game overall felt unrewarding, while its

alleged «historicity» today looks rather cartoonish. It’s still a cute

reminder of the innocence and naivete of a past epoch, and it shares the same

charm as any other Sierra product from the company’s early days, but does not

exactly manage to pile any special

charm of its own on top of the regular thing. So even if it did get its share

of accolades back in the day — it is hardly a wonder that nobody has ever heard

from brothers Ken & Doug MacNeill ever since, except for the general

knowledge that they tried to continue making money off Gold Rush! for quite a while. That said, one last addition is that I did

eventually watch some game

footage from the 2014 Anniversary Edition

by Sunlight Games and I do have to say that the original 1988 version looks

and feels magnificent next to the dreadful remake — never mind the high

resolution 3D graphics and «improved» sound, as everything in the remake

feels gray, drab, and lifeless in comparison (even the pixellated character

animations in the original made the NPCs move more like human beings than the

colorless zombies that they are in the remake). I count this as a good

experience because it did remind me that the original game still packed

plenty of imagination and, most importantly, love of the general idea of the game. Then again, pretty much

every commercial Sierra remake ever made (as opposed to certain fan-based

projects), from Leisure Suit Larry

to Gabriel Knight, always ended up

as a total suckjob. There’s just something about the spirit of that age that

apparently cannot be convincingly replicated — so just let the classics alone

in their time-honored shells. |

||||