|

Grim Fandango |

|

|||

|

Studio: |

LucasArts |

|||

|

Designer(s): |

Tim

Schafer |

|||

|

Part of series: |

Grim

Fandango |

|||

|

Release: |

October 30, 1998 (original) / January 27, 2015 (remaster) |

|||

|

Main credits: |

Programming: Bret Mogilefsky

Music: Peter McConnell |

|||

|

Useful links: |

Complete

playthrough, parts 1-7 (7 hours

21 mins.) |

|||

|

Ron Gilbert may have

been the single most important figure in the forming and initial shaping of

the LucasArts legend, but when it comes to the sheer number of achievements,

nobody can beat Timothy John Schafer — together, they are like the David and

Solomon, or the Julius and Augustus Caesars of one of the most famous empires

in gaming history. From The Secret Of

Monkey Island and its sequel, LeChuck’s

Revenge, on which he and Dave Grossman still worked as Gilbert’s

apprentices; to Day Of The Tentacle,

where Tim and Dave functioned as equal partners; and onward to Full Throttle, Tim’s first solo stab

at creating an original universe with a peculiarly warped biker theme. All of

these games were exceptional in their own way. None of them, however, beat

the multi-layered, uniquely constructed power of Grim Fandango, Schafer’s and LucasArts’ crown masterpiece and one

of the most unforgettable adventure games of all time — with heavy emphasis

on unforgettable. It might not end

up being a favorite of yours, for one reason or another, but there has never

been anything quite like it in the past, and there might very well not be

anything in the future — at least, not in the future of the videogaming

medium as it exists today. The narrative around Grim Fandango is usually constructed

with a tragic flair, since it ended up becoming the penultimate LucasArts

adventure game, followed only by Escape

From Monkey Island in 2000. Allegedly, despite mostly glowing critical

reviews and multiple awards, studio executives were so disappointed with the

game’s sales figures that the lack of commercial success became the final

straw that broke the camel’s back, with the management pulling the plug on

production of further adventure titles and firing most of the creative talent

working on them. This narrative needs an

important correction: when compared to the average LucasArts title, Grim Fandango actually performed okay,

even turning in a small profit in a couple of years — and, of course,

LucasArts games in general sold quite modestly, even when compared to their

chief rivals at Sierra On-Line, let alone various action-based titles across

various gaming platforms, so it’s not as if Grim Fandango could be seen as a particularly nasty offender. It

is simply that its market behavior was predictably similar to the behavior of

any LucasArts adventure game title — and that, by the end of the millennium,

«modest profits» could no longer satisfy those managers who finally glimpsed

the vision of genuinely big bucks in videogaming, and took it upon themselves

to decide that the age of letting visionary mavericks exert control over

software output was officially over. But who knows, they might have actually

seen a shadow of themselves in the characters of Don Copal and Hector LeMans

— Grim Fandango takes no prisoners

when it comes to exposing the cheap sins of capitalism. And that is, of course,

only one of the many things that the game does. The substantial themes that

it explores are nothing particularly new — the struggle of a few

fundamentally good, uncorrupted souls against the visibly insurmountable odds

of a fundamentally crooked, corrupt universe — but the way Schafer managed to

frame these themes is completely unprecedented, even if most of his

influences are quite straightforward. The story is vaguely reminiscent of

Terry Gilliam’s Brazil; the visual

and some of the verbal aesthetics are borrowed from Aztec mythology; the

individual characters and their relationships are projected over from classic

Bogart movies such as Casablanca

and The Maltese Falcon; the side

stories and settings show influences of spy thrillers, working class struggle

novels, and the beat scene of the 1950s–1960s. It’s a fairly crazy mix, but,

like a perfectly crafted cocktail, all of these ingredients somehow latch on

to each other in such a natural way that nothing in it feels particularly

forced or out of place. Throw in such technical achievements as the single

most brilliant musical score in LucasArts history, the most perfect voice

cast in LucasArts history, and the single best use of 3D graphical elements

in the painfully shitty era of early 3D technologies — and if you still do

not see why Grim Fandango is so

often found at the top spots of best-of adventure game lists, then I am not

sure what your criteria for rating such games would be in the first place. It is hardly surprising

that when the Tim Schafer-run Double Fine Productions gained the rights to

republishing and updating some of the classic LucasArts games, the very first

title they began work on was Grim

Fandango (later followed by Day Of

The Tentacle and still later by Full

Throttle, which is precisely the kind of order I would choose myself).

The remastered edition from 2015 is now the one that is most commonly

available in digital stores, and although it certainly improves quite a bit

on the original game’s visuals and generally makes it smoother to play on

modern systems, the improvements are nowhere near as drastic as, say, in the

case of the Special Editions of the first two Monkey Island games — after all, the original Grim Fandango was already produced in

what could be called the «near-modern» era of digital technologies. More

importantly, the appearance of the remastered edition on the market simply

helped once again draw critical and general attention to what used to be a

«cult» favorite — and the nearly unanimous positive reaction helped assert

that Grim Fandango has unquestionably

stood the test of time, and may be just as enjoyable, instructive, and

emotionally resonant in the 2010s as it was at the end of the 1990s. Whether

it will continue to be revered by retro-curious young gamers in the coming

decades remains to be seen, of course; but dethroning it will require the

emergence of an equally stunning and well-integrated cultural synthesis with

a comparably stinging satirical vibe, which is hardly a priority in the

modern day and age. |

||||

|

Content evaluation |

||||

|

Retelling the story of Grim Fandango so that it made sense to

the reader would take about a couple of pages, and even then it still

wouldn’t make sense — if you have not played the game and do not believe me,

just head over to Wikipedia where some brave, but desperate people tried to

do just that. Meanwhile, let me just try this: you play as Manny Calavera, a

lowly salesman / travel agent at the Department of Death in the Land of the

Dead, and your principal goals in the game may be defined as (a) asserting the

role of the altruistic individual in a soulless (let alone bodyless) system

of bureaucratic procedure and rampant corruption and (b) finding the meaning

of death through suffering, hard work, friendship, betrayal, revenge, and

just a subtle, faint, but super-important hint of romance. If there is one single crucial

religious-philosophical idea in Schafer’s universe, it is not a particularly

new one for humanity — the pre-Christian belief that life after death is not

all that different from life before death. Pagan deities had, after all, been

modeled after human society for thousands of years: in Chinese supernatural

fairy stories, Heavenly Bureaucracy is depicted in vivid detail as being very

closely modeled upon that of the Imperial Court, and I have little reason to

doubt that the Aztecs, whose beliefs are incorporated into the foundation of Grim Fandango, also pictured the

voyage of the deceased through Mictlán, the Underworld, as bearing

multiple similarities to the journey of a common person from his home village

to the court of the supreme ruler. The genius of Schafer was to pick up

those parallels and integrate them with the bureaucratic — as well as all

sorts of other — realities of the modern, urbanized, industrial world. This

simple move gave the game three advantages in one: a sense of familiarity

(why would the average player care about authentic Aztecan customs?), a

natural, free-flowing stream of unending hilariousness, and an intelligent,

biting satirical streak. So the Aztecs believed it took a disembodied spirit

four years to make the crossing from the first to the ninth level of the

Underworld? Well then, how about setting up an agency that deals in

expedited, luxury travel packages for the deceased that allow to make the

crossing in four minutes, provided,

of course, that the client can afford it by having led a sufficiently

virtuous life in the real world? And after setting up such an agency, why not

show that, just like any big organization in the real world, it would soon be

riddled with corruption? Schafer’s Land of the Dead is

essentially divided into two very different parts. There is the «urbanized»

area — specifically, the city of El Marrow, where you begin your trials as

Manny, and the smaller town of Rubacava, which combines the decadence of

Casablanca with the grimy poverty of Hoboken and the cultural snobbery of

Greenwich Village. These are locations in which any lovers of classic

film-noir or detective thrillers will feel cozy as heck — once they adapt to

the idea that they are all populated with ghostly skeletons instead of

flesh-clad people. These are places where sin and temptation run deep, so

that Manny has to constantly keep his bony head above water. The second part, which could, with some

very serious reservations, be dubbed «country», are the vast spaces in

between and beyond the urbanized centers. Here, you will encounter things,

entities, and dangers that are much closer to the ones actually depicted in

Aztecan myths, though some, if not most of them, still owe more to the warped

fantasy of Tim Schafer than to actual Mesoamerican sources. Forests with

odd-shaped trees, demonic spiders, fire-breathing beavers, giant octopodes,

and other weirdnesses will litter your journey and complicate your puzzling

life, even if I always had a nagging feeling that Tim did not have quite as

many feelings for those parts as he

did for the urban parts — altogether, you spend about two-thirds of your time

in the populated areas, and even when you do

get to the Ninth Underworld, it is only to go through a couple of challenges

as quickly as possible and make a dash back to Rubacava and El Marrow. And yet, these travels are essential to

the plot — they turn Manny Calavera, the city-slick wise guy, into a bit of

an Ulysses, showing him for what he really is: an outcast, destined to roam

the world (er, the «Underworld») in search of a place where he can finally

rest his head. Even though those sequences, too, have their fair share of

laughs, they also contain moments of genuine scariness (that spider scene,

ugh!), and they help you identify with and embrace your character even more

closely than the «urban» scenarios. It’s as if... well, as if The Maltese Falcon and African Queen were the same movie, or Casablanca and Treasures Of The Sierra Madre, if you get my drift. In terms of overall tropes and motives,

Grim Fandango does not try to do

anything particularly original or outstanding. There’s the Loyal Goofy

Sidekick thing (Glottis, the big orange elemental spirit with one purpose in

life — TO DRIIIIVE!); the Romantic Challenge subplot (Manny’s chief

motivation throughout the game is to atone for inadvertently ruining the

afterlife of Mercedes "Meche" Colomar); and the Bad Guys Get Their

Dues truism (Good does triumph over Evil at the end of the game in a fairly

straightforward manner). But, in Tim’s defense, the story was never supposed

to do the impossible and introduce its own system of tropes — the game is

good, but not good enough to do something that even «higher» art forms like

literature and cinema were already barely able to do by the end of the 20th

century. What it was supposed to do

was find fresh ways of acting out those tropes, and most of the time, it

succeeds at that goal. The Sidekick, Glottis the Demon, is one

of the most unforgettable sidekicks in gaming history — one part imposing and

mystical mythological entity with supernatural powers, one part loyal and

altruistic friend with a very simple and steadfast moral code, three parts

big lumpy oaf with a heavy penchant for alcohol, gambling, and the ladies

(though he does not have much luck finding the latter throughout the game).

He is largely made by Alan Blumenfeld’s vocal performance, but every time he

gets himself a bit of agency, he still steals the scene even if you turn off

the voiceovers. The Romantic Subplot is notable in that

(just as it was in Casablanca)

there is next to no actual romance — half of the game is spent tracking down

Manny’s potential sweetheart, and the other half is spent solving her

problems. We do not even get a strict confirmation that they lived happily

ever after: in response to Meche’s "Manny, when we get to the next

world, are we going to be together?", the latter can only reply

"Nobody knows what’s gonna happen at the end of the line, so you might

as well enjoy the trip". Meche herself is extremely far from our ideal

of a Strong Female Character — not only does she have next to no agency

whatsoever (most of the time, it is up to Manny to get her out of one drag or

another), she is also shown as not particularly smart or perceptive; yet,

like one of those saintly female characters from a Dostoyevsky novel, her

importance is that of a shiny moral beacon to justify the protagonist’s very

existence. As far as the Bad Guys are concerned,

the game’s major and final boss, Hector LeMans, is not a particularly

interesting figure (he only appears in two big scenes at the end of the game,

and is rather predictably caricaturesque), but the auxiliary ruffian, Domino

Hurley, feels like he was specifically written to feel like the most

irritating villain in villain history. He is one of the few characters in the

game whom Manny cannot beat in a battle of wits — not once! — and who is ultimately overpowered by accident (or

destiny) rather than the hero’s focused efforts. Many of us have probably

encountered our own Domino Hurley in real life — the smart, eloquent, hard-working,

cynical, ruthless, narcissistic over-achiever who you’d like to strangle except

nobody else would understand why — and his presence in the game is an

uncomfortable reminder that you probably would not be free of such characters

even after death. The greatest thing about Grim Fandango, however, is not its

storyline or any particular personality of any of its particular characters.

The greatest thing about this game is its dialog — dialog so utterly

brilliant and so unbelievably consistent in its brilliance that it makes every single character come to most

enviable life, one way or the other. If this game were an actual animated

movie, it’d put to shame every single Pixar production ever made; heck, we

might be talking Tarantino or Coen Bros. level here, maybe just a tad

simplified for consumers’ sake (alas, this is a video game, after all). Be it the good guys or the bad guys,

the main characters or briefly appearing NPCs, the intellectuals or the hoi polloi of the Land of the Dead,

they all have a lot to say and they say it in such ways that, were I only to

start, it would take me hours to type out all of my favorite quotes. I shall

resist the temptation and give only one example — from the mouths of three

neo-Marxist lefties huddled together in a corner of the Blue Casket,

Rubacava’s favorite hangout for lovers of modern jazz, beat poetry, and

progressive views. These guys have a particular bone to pick with our boy

Manny after his acquisition of the local casino ("you smell like bacon

and oppression, man! no room for the bourgeois in our revolution!"), and

show no signs of softening up even after Manny takes the stage and delivers

his own improvised piece of beat poetry: Manny: So,

what did you think of the poem? Revolutionary #1: I liked it. It was sad and beautiful, like my mother. Revolutionary #2: I despised it. It was too short and said nothing to me, like my

father. Revolutionary #3: I had no feelings about it. It was aloof and licked itself too much,

like my cat, Mr. Trotsky. Best of all, this is not just «funny

for funny’s sake», as was the case with much of the dialog in Day Of The Tentacle — a great game in

its own right, but one that feels extremely lightweight in the company of Grim Fandango. Schafer’s masterpiece

raises all sorts of issues — morals, politics, social justice, work ethics, discrimination,

relation between sexes, even parenting (the annoying, but cute Angelitos, which Manny and Meche all

but adopt during the game). At the very start of the game, one of the first

things you can do is «Look» at the first person you meet: "It’s my boss’

secretary, Eva", says Manny in a fairly innocent tone, and is

immediately put back in his place — "It’s my boss’ whipping boy,

Manny". A trifle, but a meaningful one, and the game has literally

hundreds of these. Herein also lies the problem: Grim Fandango does require a certain

level of education to be enjoyable in the way in which it was designed to be

enjoyable. If you know next to nothing about Marxist ideology and do not

recognize the basic melody of The

Internationale; if the name "Robert Frost" is as foreign to you

as "Bhumibol Adulyadej"; if you have never seen Casablanca or On The Waterfront; if you think that "beat poetry" has

something to do with the Beatles; if you are too old to remember the glory

days of ‘This Little Light Of Mine’ — if you are all these things and more,

then Grim Fandango will be a blank

slate to you, and most of the depth and humor will be lost. (To avoid

accusations of snobbery, I shall gladly admit that at least some of it is

most likely lost on me, as well — there may be tons of cultural references in

the game that I have not been able to pick on). Of all the LucasArts games in

existence, this one is the most intellectually loaded — and, consequently, it

just might be one of the most intellectually loaded games of all time, which

makes all the more ironic its status as that of the game that finally ruined

LucasArts. But apart from being a true

intellectual’s delight in the world of «lowbrow» video games, Grim Fandango also has a heart, which

it does not exactly wear as openly on its sleeve as Glottis the Speed Demon

wears his, but demonstrates in subtle, delicately endearing ways. There is no

moral ambiguity in the story: although most of the characters are

multi-dimensional, each one is either fundamentally good, including our main

character and his sidekick, or fundamentally corrupt, including Domino Hurley

and the hip-chic chick Olivia Ofrenda, whose impeccable taste in clothes,

poetry, and general verbosity does not prevent her (or maybe is correlated

with her) inability to make the right choices in life (Manny: "You know, you have a really bad taste in

men" – Olivia: "No, I

have a taste for really bad men. There’s a difference"). And some of

that proverbial fundamental goodness is best felt in minor side characters —

such as the melancholic old cuckold Celso, who simply goes and gets back his

wife after she abandons him, with no consequences; or the jaded old morgue

keeper at Rubacava ("my secret to happiness, Manuel, is that I have the

heart of a 12-year old boy... I keep it over here in a jar, would you like to

see it?"); or the barnacle-covered ex-sailor Chepito, stubbornly

determined to reach the Ninth Underworld on foot by walking across the bottom

of the ocean. All of them contribute to the «nice» feeling of the game

without ever resorting to sentimentality, simple clichés, or cheap

manipulation. The latter observation is extremely

important — one reason why Grim

Fandango in its canonical form could never be adapted into a Pixar movie

is that there are no specific moments in it when the director waves his baton

and laughs temporarily give way to tears. Even when good characters die (like

the sweet girl Lola in Rubacava), they do so in a semi-bizarre, semi-parodic

way («sprouting» after a hit from the bad guy’s plant-loaded gun), which

prevents us from taking things too seriously. Even when Manny and Meche get

together, the state of their union remains unclear (is there actually such a thing as proper romance after death?).

Even when Glottis is lying on his deathbed, your feelings for the big orange

dude are mixed with the realisation that... he is, after all, a big orange

dude. Some might see this as a flaw of the game, and I would, too, except

that the game does make you feel

about the characters. It’s just that they always walk a thin, perfectly

balanced line between the pre-modern and the post-modern, making Grim Fandango an absolutely unique

experience in the world of videogaming. |

||||

|

For me, Grim Fandango is first and foremost an immersive interactive

story; nothing about it thrills me as much as exploring each dialog tree with

each character to its deepest depths (and some of the depths are quite deep).

But I do admit that for most people who come in contact with it, Grim Fandango will first and foremost

be a puzzle-based adventure game — and for most of those people, their

feelings toward it will largely depend on how challenging, satisfying, and/or

frustrating they are going to find those puzzles. (And some of those people

might even skip through most of the dialog, which, to me, would be the

equivalent of fast-forwarding through every conversation in Pulp Fiction just to see some action). And nobody could ever argue that Tim

Schafer did not take that part of the experience seriously: unlike Sierra,

many of whose mid-1990s projects went way too far in the direction of turning

adventure games into interactive movies, LucasArts were never in a hurry to

rid the player of his fair share of solid, sweaty challenges. There is not a

single episode of the game where you would be deprived of a good chance to

get stuck — and a few episodes, usually the ones covering Manny’s

«countryside» travels between the «urban» centers, seem almost exclusively

dedicated to getting you in a tight place. In terms of general difficulty, I

would say that Grim Fandango is one

of the harshest LucasArts games, at least from the «talkie» generation (early

titles from the 1980s have to be judged on their own terms). The harshness, depending on where

precisely you are at in the game, can be of two types. One type is Outrageous

Harshness: puzzles that require you to take actions which follow a highly

specific logic of the Land of the Dead Universe (read: Tim Schafer’s crazyass

brain) — nothing new for you if you come to the game straight from Day Of The Tentacle or Monkey Island, but a doggone

nerve-kicker if you simply pick it up because somebody recommended it to you

as one of the best games of all time. For instance (spoiler!), early in the game, in order to get a batch of pigeon

eggs from the roof of a building, you have to drive the pigeons away by

making a loud noise — which can be produced by popping an inflated balloon

that you can buy from a street vendor beforehand. But you cannot simply pop

the balloon all by yourself; what you have to do is conceal it at the bottom

of an empty water basin by spreading some breadcrumbs over it, whereupon the

silly pigeons congregate all over the crumbs and inadvertently pop the

balloon themselves. Note that if you just

spread the breadcrumbs, the pigeons will still congregate, but they will

quickly peck all of them away while you are prohibited from taking any

actions in the meantime — merely because this would interfere with Schafer’s

evil plan. Success is achievable, but it does go against conventional logic,

and can become quite an impediment for those who are not ready to go that

extra mile. And this is actually one of the easier two-step puzzles in the game. The other type of harshness is

Confusing Harshness, which hits you with full force in Rubacava. Before that,

El Marrow is largely restricted to a few rooms inside the Department of Death

and a couple outside areas, while the travel route from one town to another

is fairly straightforward. But once you get to Rubacava, the landscape

becomes a disorienting sprawl, a twisted jumble of entertainment venues and

industrial areas where your success typically depends on picking up stuff in

point A and employing it in some completely different context in remote point

B. Not that this is so completely different from situations in other

LucasArts games — Monkey Island 2

and Day Of The Tentacle are all

about this — but for some reason, Rubacava used to really disorient me, perhaps because of the game’s odd graphic

style, or perhaps because I used to mix up all these endless casinos. Worse,

the game often sends you searching for objects which you are not sure you even

need in the first place: for instance, a lot of attention is quickly drawn to

Carla the Security Guard’s metal detector, but even after you go to all the

trouble to get it, you might not be fully sure of why you did. From a purely aesthetic point of view, Grim Fandango’s puzzles are not

particularly memorable or ingenious — nothing here to spin tales off like you

could for Day Of The Tentacle,

whose «send a hamster sweater 200 years into the future» or «make George

Washington chop down his last cherry tree» moments are truly the stuff of

legend. Every once in a while you get a solid chuckle of an action, like

supplying the linguistically struggling Worker Bees with a copy of Das Kapital, or manipulating your own

roulette wheel to have the Chief of Police shut down your venue, like Claude

Rains in Casablanca, but more often

you have to content yourself with fishing metal detectors out of cat litter

or concocting rocket fuel for Glottis or something even more routine. It is

fairly clear that with Grim Fandango,

story came first for Tim, and challenges came second — but honestly, I do not

blame him. It could even be argued that a great interactive story and a great set of adventure puzzles

would always have a hard time sharing the same bed. To spice things up, many of the game’s

sequences are strewn with brain-wrecking logical challenges, whose design is

quite neat and original, but can seriously mess up the game’s pacing if

you’re not exactly the macro-IQ type. One challenge, for instance, involves

correctly lining up a wheelbarrow to exert just the right amount of pressure

on a mechanical contraption «sucking the marrow out» of a tree so that

Glottis could demolish it for some useful components (the source of the

classic line "...from now on, we

soar like EAGLES... on POGO STICKS!!"). In another, you have to

manipulate a set of anchors so that it could properly entangle your ship and

tear it in half, making it possible to escape from the assassins who have

boarded it. Still later, you have to free Meche by baring the guts of a

mechanical door and carefully arranging the tumblers in the correct order (DON’T forget to find a way to hold

them in place — otherwise, it’s all back to frustrated square with a

depressed "oh, and I had them so nicely lined up and everything...").

I am not a big fan of puzzlers like

these, but I cannot blame them for being poorly designed, and I can’t see

them as not fun for those who are funs of puzzlers. Actually, I

think there was only one genuinely frustrating bit — the one in which you

have to manipulate a magical rotating direction sign to uncover a secret

underground entrance; not because it was all that difficult, but because it was

a classic example of doing something without understanding what it is exactly

you are supposed to do, a flaw that this challenge shares with quite a few of

the object manipulation-based puzzles in the game. At least getting stuck in one place or

another gives you a nice chance of falling upon all sorts of unpredictable

actions — for instance, in classic LucasArts fashion there is one «universal»

object, the Rusty Anchor card, which can be used on just about anyone, often

with endearing results (Olivia Ofrenda will recite one of her poems, while

Glottis will be goaded into singing an entire song, which even counts as a

separate Achievement in the Remastered version). Also, perhaps the most

hilarious thing about solving many of the game’s puzzles is the use of

Manny’s foldable Grim Reaper Scythe as a universal tool — you can have it as

a weapon, an opener, an arm extender, a door latch... only once, I believe,

do you actually get to use it the way it is supposed to be used, and even

then impersonating Death does not feel like a particularly sinister business. |

||||

|

I probably already spilled most of the

beans on this while discussing the quality of the game’s dialog, but a

brilliant script is one thing, and its vivid implementation in a video game

is quite another. So what does Grim

Fandango actually feel like, and to what extent does it make you want to

linger on and on in its universe? How is it, generally speaking, to live the

daily life of Manuel Calavera, and do you actually get any extra insight into

the guilty conscience of the Grim Reaper? Unfortunately, the world of Grim Fandango is not an open one —

there is no way you could freely roam through all the Nine Realms of the

Underworld, and Rubacava is pretty much the only place where you can «take a

walk» across a relatively vast landscape, one that even incorporates a few

screens here and there just for the

sake of atmosphere (like the giant cat statue near the race tracks, for

instance). Even so, it still feels like a place of great mystery and wonder

where you quickly get the craving to explore every nook and cranny for dark

and unpredictable secrets or at least funny jokes. Alas, you get far fewer of

those than you’d like to, which is still not an excuse not to explore each

room diligently for every hotspot. There is nothing like, for instance,

clicking on a terrifying Mesoamerican statue of some infernal deity and

hearing Manny ruminate, "ah, the

old head of the department... way before my time. I heard he was a total

slave-driver". That is the

atmosphere of the game in a nutshell — grotesque combinations of historical

and modern, mythology and bureaucracy, fantasy tale and film noir. While Manny’s adventures in El Marrow

are more Terry Gilliam’s Brazil and

his challenges in Rubacava more Casablanca,

there is no rigid distinction — elements of surrealist dystopian fantasy and

romantic nostalgic noir are tightly intertwined, making you simultaneously

enamored with the universe and disgusted with it or, at least, understanding

that if the Land of the Dead were a reality, you might not want to eagerly

trade your place in the Land of the Living for a ticket on the Number Nine

train. People in the Land of the Dead, just like everybody else, spend their

days doing pointless chores, getting harassed by rigid, heartless

bureaucrats, drinking, gambling, and complaining about how "death makes

sad stories of us all", in the words of the game’s most depressed

character, the wise coroner Membrillo; "Manny, we’ve given up, all of

us", he adds when asked about why he does not go off in search of the

legendary Ninth Underworld. This does indeed give a whole new meaning

to the idea of the Grim Reaper: the guy is Grim not because death is such a

serious business, but because death has turned out to be merely an indefinite

extension of life. Note that even if the game formally has a happy ending, we

are never actually shown the

promise of peace and redemption that lies behind the gates of the Ninth

Underworld — even at the very end, all that remains is a hint and a promise.

The entire game is just one giant "we’ve gotta get out of this

place" enterprise, and playing it according to one’s generic ideas of

escapism is a questionable affair indeed. Even the many Imaginary Wonders of

this exclusive place are usually dangers — black spiders, demonic beavers

with huge teeth and flaming tails, giant squids, hungry tank-like alligators,

you name it. There is no straightforward horror, gore, or otherwise

disturbing imagery (largely because all the horror and gore are run through a

surrealist filter — dismemberments in the Land of the Dead never look as

gruesome as they do in real life, or even in Mortal Kombat); there is even no suspense and tension as such,

because you know for sure that most of the danger is just implied (especially

since it is impossible to die in the game, because not only is this a

LucasArts game, but you are already dead... could get «sprouted», though).

There is only this feeling of an endless, grayish, inescapable drag — yes,

more or less the same as probably felt by Rick Blaine, trapped in his own

groundhog day way back in Casablanca. And, like all the best heroes of both

dystopian nightmares and somber noirs, the only way to alleviate this drag is

humor. Even if Grim Fandango is one

of the few LucasArts games that could avoid being slapped with the «comedy»

label, it is still funny, nay, hilarious whenever the characters open their

mouths. Jokes fly in all directions — mean, nasty, sarcastic, bleak, cynical

jokes, as Manny takes it out on the entire world, while his antagonists, in

turn, take it out on him. Other characters, such as Glottis or Manny’s sucker

clients, are usually the butt of the jokes, but everything they take is

well-deserved (for instance, Manny will rather joke about Glottis’ addiction

to alcohol than about the demon’s weight). Said jokes include some of the

most magnificent English-language puns I’ve ever come upon (e.g. Manny,

looking at Eva’s office table: "Could

I take your hole punch?" – Eva: "HA! I doubt you could take my HALF punch!"), and even some

of the best references to class struggle in a video game (Police Chief Bogen,

while arresting a worker bee agitator: "You know, I always thought bees come in two colors: yellow and black.

But you look all RED to me, my friend!"). It is this combination of permanent

depression and razor-sharp humor, ultimately, that makes up the game’s atmosphere

— embodied in the character of Manny Calavera, possibly the most outstanding

world-weary jokester in video game history. Once you have spelled this out,

it becomes even more understandable why the game never attracted a mass

audience: people are typically attracted to promises of hope and salvation,

but Grim Fandango basically

substitutes that promise with acidic humor, mean irony, and a more

bittersweet than optimistic ending. Yet for those who are not afraid of a

little acid sprinkled in their spirits, the game may simply work on so many

levels. You can play it just for the jokes; you can take it seriously and

begin empathizing with the characters; you can make your own hunt for all the

cultural references and influences; you can stop and think if the game makes

any original points or is simply a combination of all the borrowed

ingredients. You could probably write a thesis on it — or, of course, you

could just play it as one more adventure game and go away with one of those

«yeah, it was nice, but I didn’t particularly care for the puzzles» feelings.

Always your choice. |

||||

|

Technical features Note: The following section mainly describes the 2015

Remastered Edition of the game, which is not tremendously different from the

original, but special references will be made to the original whenever

necessary. |

||||

|

«3D or not 3D», that was

the question for so many old-school game studios in the late 1990s, and most

of those who replied in the positive have long since paid the price — approximately

95% of videogames made in 3D, or with elements of 3D, at the time, are — and,

to be honest, have always been — essentially unwatchable, which can also make

them unplayable if you are not able to get over the disgust. Sierra, for

instance, fell flat on their face with the abominable King’s Quest VIII, also released in 1998; similarly abysmal 3D

graphics are one of the few things that deeply mar Funcom’s The Longest Journey from 1999, and so

on. Yet everybody felt that, want it or not, 3D graphics clearly define the

future of gaming, and it can be reasonably argued that without these early

visual horrors, we would never have gotten where we are today with the

technology. The adventure game

department of LucasArts only lived long enough to release two games in true

3D: Grim Fandango and Escape From Monkey Island. The latter,

unfortunately, shared all the typical flaws of early 3D titles — but Grim Fandango, on the other hand, is a

perfect example of how a genius designer can work around the limitations of

technology and even use some of them to the product’s benefit. Just as the

studio pulled the plug on its classic SCUMM engine and made its coders design

a 3D-based replacement, the idea for Grim

Fandango came along — which is why the new engine was titled GrimE, since

it was specially tailored to the needs for Grim Fandango. However, the engine was not capable of handling a

full-scale 3D environment: neither in Grim

Fandango nor in Escape do you

actually have the ability to wiggle the camera around. Instead, both games

used pre-rendered 2D backgrounds with 3D-modeled objects, so that during a

cutscene or while walking around, you could get different camera angles of

the same environment without having to redraw it from scratch. The character models,

however, were fully three-dimensional, capable of turning, twisting,

rotating, and moving parts of their bodies based on their own independent

trajectories; and this is where the specific genius of Grim Fandango comes in. Where the 3D models of Escape From Monkey Island look hideous

because they try — in vain — to model the shapes and movements of actual

people made out of flesh and blood, the 3D models of Grim Fandango are based not on the living, but on the dead — more

precisely, the Mexican calaca

figurines, inherited from Mesoamerican art. And because the artists and

coders were essentially modeling bones

rather than skin — objects that, by

nature, are more, uhm, pointy and polygonal than the smooth curves of human

skin — they essentially found the

single perfect means of turning the deficiencies of late 1990s 3D modeling to

their advantage. Simply put, Grim

Fandango is the only game from that era that I know of which can proudly

say about itself: "yeah, I know it looks weird, but it was intended to be that way!" Not

even Half-Life, which did

unbelievably impossible things with 3D graphics that same year, could make

such a claim. Sure enough, characters in Grim Fandango all look grotesque — but

so do the calacas, and who are we

to insist that people do not take on grotesque shapes in the afterlife? The

important thing is that the shapes of the inhabitants of the Land of the Dead

exhibit realistic behavior. They walk around, they flap their arms, they

scratch their heads, they puff on cigarettes in ways that are not only fully

believable, but actually manage to visually emulate the movement style of

those old film noir movies, or of people in hip scenes from the 1950s

circuit; Olivia Ofrenda is not merely dressed

as a hip jazz beat chick, she moves

like one (when she is not glitching, that is, which happened several times in

my Remastered Edition playthrough). The perfect sign that everything is going

to be alright is found right at the start of the game — we first get to know

Manny Calavera as the Grim Reaper, an imposing, scythe-wielding figure in a

dark cloak, moving smoothly, sinuously, and imposingly around his client.

Once the client is out of the office, Manny takes off his cloak, revealing a

couple of walking supports, and quickly turns into a small, pudgy,

short-legged guy, not even particularly dignified, let alone imposing — and

all of that is detailed, smooth, and utterly natural in a way that would be

unimaginable for «regular» 3D graphics at the time. One might think that it

would be a difficult task to convey emotions, let alone facial beauty, for a

bunch of 3D sprites with naked skulls instead of regular heads. Indeed, all

the characters, be they formerly human or Demons (like Glottis with his huge

orange head), have rigidly painted faces with holes instead of eyes or noses,

as would befit a skeleton. But they still have mouths with teeth (as also

befits a skeleton), and they are still free to move their heads independently

of their bodies — and this, believe it or not, goes a long way in

establishing character. The bad guys, for instance, have fairly scary teeth,

as opposed to the good guys with smaller, cutesier mouths; they also tend to

have their faces painted in a more sinister fashion, or a more grinny one if

they’re ironic assholes (Domino). Eyeshapes, brow shapes, skull shapes — they

all matter when it comes to determining who is the dashing Dapper Dan, and

who’s gotta be the Hunchback of Notre-Dame in this enterprise. Besides, at

least all the calacas are allowed

to wear clothes, which they do in all sorts of striking fashions (usually the

ones that went strictly out of style by the beginning of the 1960s, or

earlier). You might not be able to fall in love with Meche based on her

facial beauty (though it is certainly in the eye socket of the beholder), but

you won’t be able to condemn her sense of fashion — modest, but stylish and

elegant. For all the inspiration and

brilliant work that went into creating and animating the Dead, one should

also not forget the unique art style of the pre-rendered backdrops. It is

here, more than anywhere else, that one really feels the Mexican or, rather,

Mesoamerican influence: traditional Mayan and Aztecan decor are all over the

place, particularly in El Marrow — by the time we get to Rubacava, there is

more stylistic diversity, with a mishmash of more Mexican architecture, Art

Deco (note the interiors and exteriors of the Blue Casket especially), and

just general tasteless gaudiness when it comes to hangouts for the rich and

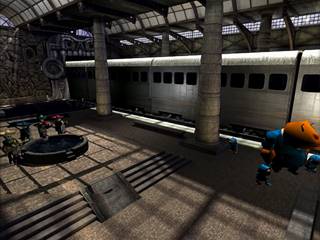

famous. Particularly impressive is the train station at the Gate to the Ninth

Underworld, whose shape is clearly influenced by the Mayan pyramids — this is

the closest that the game’s artists get to reproducing an

almost-authentically looking «native American environment», though on the

whole, Tim clearly did not want to mess too

much around native imagery, architecture, and rituals, because those subjects

would probably push the game too much into Solemn-Serious territory and ruin

the overall atmosphere. One particular aspect worth

a special mention is the graphic depiction of plants and flowers — according

to the lore of Grim Fandango, these

symbolize Death in the Land of the Dead, as nothing can be worse than getting

«sprouted» (shot by a bunch of seeds). The several cases of «sprouting»

documented through the game are depicted in grizzly detail, as greens and

flowers shoot through the body of the injured, turning him or her into an

undead green lawn. If you get seriously immersed in the game, you might never

look at a flower in quite the same way again... much less at a lush, dazzling

flower meadow, pretty much the equivalent of a mass execution site in the

Land of the Dead. Anyway, the graphics of the

game were so good for 1998 that

when you load up the 2015 remastered version — which, like all LucasArts

remasters, graciously lets you toggle between the original and the remastered

graphics — you will be surprised to see just how little has been changed. In

fact, the backdrops look almost untouched; the biggest changes are in the

upscaled character sprites, smoothed out, polished, and depixelated.

Amazingly, there are even certain aspects of the older characters that are

better than the remasters — for instance, the balance of light and shade was

handled in a more complex manner, as the remaster simply eliminates much of

that shadowplay; in a game that tries to evoke the feel of classic noirs,

this solution may not have been the optimal one. Do not expect the same kind

of magnificent facelift that remastering brought to Day Of The Tentacle — then again, with the crucial five year gap from

1993 to 1998 between the two games, which probably brought about the single

biggest jump in graphic resolution ever, this warning is kind of

self-understood. |

||||

|

While the game’s visuals

are certainly responsible for a huge chunk of the game’s atmosphere, they are

almost nothing compared to the role that sound plays in it — in fact, the

best way, in my opinion, to enjoy Grim

Fandango is late at night, with a weighty pair of headphones over your

head while the rest of the family is sprou... uh, I mean, sleeping; like the

vintage noirs that it emulates, the game is decidedly a nocturnal experience. The musical soundtrack was

composed almost exclusively by LucasArts veteran Peter McConnell, who pretty

much poured all his accumulated musical experience into the process.

Essentially, it is a jazz soundtrack, taking its cues — depending on the

specific context within the game — from either «entertainment jazz» (big

bands, swing, Benny Goodman, that sort of thing) or «intellectual jazz» (bebop,

post-bop, Charlie Mingus, you get the drift). However, in accordance with the

game’s general art theme, there is obviously a lot of Mexican influence as

well (particularly on the streets of El Marrow), ranging from mariachi band

themes to classical flamenco guitar; nor is McConnell an enemy to traditional

Hollywood classical orchestration, which he likes to incorporate during

climactic moments. I couldn’t say for sure

that the soundtrack is really heavy on catchy tunes (I did memorize a lot of

the music, but that might simply have been due to overexposure while trying

to get unstuck with the puzzles, at which point you might be able to memorize

an entire Henry Cow album); but it does a perfect job of capturing the

emotional / atmospheric essence of nearly each episode of the game. In

cutscenes, the music is well-tailored to the unfolding of events — a good

example is the very first scene, where Agent Calavera is introduced as an

«intimidating» Grim Reaper, in the process of terrifying the poor freshly harvested

soul with images of the harsh journey to the Ninth Underworld — backed by a

menacing, growling, Wagnerian arrangement for the brass section; then, just

as he turns from creepy Doomsayer to seductive Sales Agent ("...wouldn’t you rather cross the Land of

the Dead in your own sports car?"), the brass section completely

switches gears and goes into a big band lounge theme that is much more

suitable for a hot stripper dance. And this,

by the way, is the moment when you realize that the game is not going to be a

horror-themed one, but a dark comedy — and you wouldn’t realize it that

quickly if you were playing with the sound off. Of course, this trickery

only works in the movie-like cutscene parts of the game; wandering around the

streets and corridors of El Marrow and Rubacava is accompanied by more static

musical pieces. Static, that is, but not exactly ambient-ish and most

definitely not elevator-ish: this is a loud and proud soundtrack which

actually dares to mess with your attention — you might even want to lower the

volume at one point, so as to hear the dialog better and / or not to get too

distracted while trying to think your way out of some mess or other. The

climactic battle between Manny and Domino atop the latter’s octopus-powered

submarine, for instance, is accompanied by an aggressive half-Mingus,

half-Stravinsky «Rite of Spring

meets Black Saint And The Sinner Lady»

theme which I almost want to hear more than Domino’s snappy roasts ("...oh please, Manny, save the comic book

one-liners for when you’re winning!"). The themes also know fairly

well when to turn properly, rather than mockingly, sentimental — almost

never, that is, except for a carefully selected bunch of moments, like the

final farewell scene where it helps you understand that all through the game,

you actually cared much more for Manny, Glottis, and Meche than you were

willing to realize or admit. The Remastered version

ended up seriously tinkering with the original soundtrack; McConnell was not

satisfied with the audio quality of the original digital recordings, and

opted to re-record much of the orchestration with the Melbourne Symphony

Orchestra. I admit that I have not seriously compared the original and

re-recorded tracks, so it is possible that some new themes or arrangements

were added; but the re-recorded orchestrations seem to be more or less

faithful to the original score, so I’m assuming it all had to do more with

clarity of sound than any dissatisfaction with the actual music. If you have

free time to kill, you can do the comparison between the original score and the

remastered soundtrack

on your own. Equally good care was taken

of the voice acting cast, where the trick of mixing in an authentic Mexican

feel with echoes of Hollywood noir was even more difficult to implement.

However, in Tony Plana, a Cuban immigrant with 20 years of acting experience

on stage and in cinema, Schafer found the

perfect Manny Calavera — Plana actually helped out with some of the dialog,

inserting bits and pieces of Spanish-American slang and occasional Spanish

quips for authenticity’s sake, while at the same time nailing the grizzled,

world-weary, disillusioned, but still moderately idealistic nature of the

title character. There is not a lot of versatility in Manny’s voice, but

there are enough subtle shades and overtones to present him as an emotionally

complex persona, capable of anger, sarcasm, sentimentality, and compassion

depending on the situation. Manny Calavera belongs to the class of «noble

losers» — people who have been trampled by life (or, in his case, death)

mainly because they themselves refused to trample on anybody else’s — but he

is also a bitter cynic and a bit of a troublemaker, and Plana captures all

these complexities and spices them up with a sweet touch of a Spanish accent.

Hay te huacho! Second prize in the game unequivocally

goes to Alan Blumenfeld’s performance of Glottis, the Speed Demon, whom he impersonates

like a bit of a cross between Tom Waits and Louis Armstrong, combining the

grizzly roughness of the former with the big-naturedness of the latter.

Visually, Glottis is not the most impressive character in the game — his huge

polygonal orange head makes him rather plain, more reminiscent of a large,

roughly manufactured plush toy than proper Hellspawn; but Blumenfeld more

than makes up for this with his vocal delivery, clearly vying for the title

of «Sidekick Most Likely To Be Kicked Out Of A Bar Every Saturday Night».

Unlike Plana’s Manny, who never over-emotes even in the most emotionally

charged situations, Blumenfeld’s Glottis over-emotes nearly all the time — even when lying on his

potential deathbed — which makes the two characters into proverbially perfect

polar opposites with magnetic attraction to each other. And, of course, your

life is not complete until you’ve heard Glottis sing "Rusty Anchor"

or yell "LUMBAAAAGOOO LEMONAAAAADE!" in that kind of voice which

breaks windows and causes minor earthquakes. The rest of the cast is generally less

distinctive — mainly because there are so many roles, they all have a rather

limited time window to impress you — but everybody more or less hits the

mark. Manny’s romantic interest Meche, voiced by Maria Canals Barrera (also

of Cuban descent), is a bit cold and flat, but this is precisely what is

required of the character: Meche is designed as a passive character, an ideal

figure and a guiding light for Manny just through the mere fact of her

existence, not because she is actively working her charms on the guy or

anything. Patrick Dollaghan as Domino Hurley generates just the right amount

of annoyance, obnoxiousness, irritation, and disgust for us not to lament his

passing. Paula Killen as Olivia Ofrenda nails the hip Fifties’ New York jazz

club chick to perfection, despite being born in Los Angeles in 1966. And a

special thank you goes to my personal favorite — old grumpy guy Kay E. Kuter

as Dockmaster Velasco, a role that suits him even better than that of

Griswold Goodsoup in The Curse Of

Monkey Island (but not better than that of Werner Huber in Gabriel Knight 2). Oh, wait — actually, my major prize for

minor support role goes out to Terri Ivens as Lupe, the Cloakroom Girl in

Manny’s casino, who voices each of her lines with such teenage exuberance,

you’d think she was on a heavy blended mix of black coffee and amphetamines

all of the time. Also, music fans will be pleased to know that the role of

Police Chief Bogen, modeled somewhat after Claude Rains’ Captain Renault in Casablanca, went to none other than

Barry Dennen, the original Pontius Pilate in Jesus Christ Superstar (both the original cast and the classic

movie) — whether this was intentional or not, I do not know, but I do know

that the guy went on to have a rather prominent career in video game voicing

after Fandango. Which, curiously, is not at all the

matter with a large part of the cast: most of the actors here are ones who

you are more likely to encounter in second-rate TV shows over the years than

in award-winning video games. For many, Grim

Fandango was their first experience in the medium, and for quite a few,

also the last — which makes it all the more impressive how well they all work

together in the end. |

||||

|

Interface With its new engine, Grim Fandango at the time of its release

signaled some major changes in game mechanics. Apparently, as was the case with

most of the early 3D-based PC titles, the engine had problems accommodating

mouse control — so, along with Escape Of

Monkey Island, the original Grim Fandango

was one of two LucasArts games that did not use the mouse at all; so much for

the old «point-and-click» ideology. Instead, you were supposed to guide Manny

with your keyboard — but, since Manny was a 3D gentleman who could be rotated

around his axis, he did not move in all four directions, but could only advance

whichever way he was facing (with the Up arrow), while the other cursor keys

were used to make him spin to the right or the left. These so-called «tank

controls» were not invented by Tim Schafer — they had already been

implemented in quite a few early 3D games, most notably the early Resident Evil titles — but,

apparently, the man loved them,

claiming that the tank control scheme lets you get even closer under the skin

of your character, since it more or less models the way you move in real life.

In fact, he loved them so much that even though the Remastered edition of Grim Fandango brought back mouse

control and allowed you to forget about the tank scheme for good, there is

still a separate Achievement in the game for playing it from top to bottom

with the tank control movement scheme. Needless to say, this is the only

achievement that I have missed out on in my latest replay of the game, and,

apparently, so did most of the other players (my Steam library lists 3.4% of

people who got it, and all of them probably have worse OCD than I do). I

frickin’ hate tank controls — this

is one of several reasons why I could never get along with those early Resident Evil titles, along with the

really awful 3D graphics — and as somebody who never had any problems

identifying with King Graham, Roger Wilco, or Larry Laffer in the early days

of PC gaming, Schafer’s logic in this matter seems painfully artificial to

me, more like trying to justify a shitty choice forced upon the designer by temporary

technological limitations than anything else. There are defenders of the

scheme out there who claim it is merely a question of getting used to a

different pattern, but in reality it is a painfully counter-intuitive pattern:

when one’s brain perceives four seemingly equivalent symbols on the keyboard (up,

down, right, left arrows), it wants to interpret them as having equivalent

functions — having to remember that two of them move you forward or backward from

place to place, while the other two spin you around on the spot, requires

constant brain activity which, hum hum, could probably be spent on something more intellectually and emotionally

rewarding than a pat on the back from Tim Schafer and an extra achievement in

your Steam library. Lack of the mouse also meant an

impossibility to inspect or manipulate hotspots by clicking on them; if I

remember correctly (I no longer have the original game, and the remaster does

not preserve the old scheme), what you had to do in the original was use

keyboard shortcuts to do that whenever you were near the object in question,

and since it was not highlighted, this made things confusing. (In Escape From Monkey Island, this would

be partially rectified by having a floating list of objects at the bottom of

the screen; but it was still a hassle, since the list could change or

disappear with the slightest movement of your character around his axis). With

the auspicious re-introduction of the mouse in the Remastered version, all of

that is no longer a problem — tank controls can be forgotten, and not only

can you simply move Manny in the required direction by clicking on it with

the mouse (double-click to make him run rather than walk), but you can also

hover the mouse over any object to get a small option wheel (Look, Talk, Use,

etc.) to do with it whatever you please. One more cumbersome option of the

original’s interface that added a nice artistic touch but quickly became a

hassle was the inventory system. Instead of opening the usual pop-up window where

all your belongings would all be neatly arranged, the Inventory option shows

you a close-up of Manny’s torso with only one object in his hand, and to

choose the right one you have to go through all the inventory one object at a

time, with a brief, but annoying animation of Manny putting the current

gadget back in his inner pocket and extracting the next one instead. This can

extend the time needed to use a particular thing from one or two seconds (open

pop-up window, click on one of the objects, close window) to a good 10–15 — and,

once again, apparently Tim was so proud of this invention of his that he left

the same scheme in the remastered version without any amendments whatsoever,

the bastard. (At least this way we can really tell that Manny keeps his

scythe close to where his heart used to be — along with all the 10 or 20

items or so he is allowed to carry on him). The clumsiness of the interface would

not, perhaps, be such a problem if Grim

Fandango was not so heavily dependent on puzzles that require precision

of action or quick timing. There is, for instance, a sequence where you have

to get inside an elevator, send it upwards, mount a forklift inside the

elevator, and jam its prongs into the two gaps in the door so that the lift would

stop in between the two floors. Figuring out what you need to do is relatively easy, but actually getting to

do it in time, and with the required accuracy, is something I’d probably

never manage to do with tank controls, and even without those it took a few

tries to get the hotspots to obey me. Fortunately, at least most of the puzzles are not timed; and

since you can never die in the game, the worst you have to suffer through is

a series of rinse and repeats. Unfortunately, players are fairly

picky, and comfortable game mechanics is what most of them require above

everything else, so chalk up one more reason why Grim Fandango became a cult favorite rather than a smash success.

Such comfort had never been a top priority for the geniuses at LucasArts, who

prided themselves first and foremost on their astute and logical puzzle

design, and ultimately paid full price for it. And while the Remastered

edition of the game does solve a lot of those problems, it does not solve

them all, and it certainly solved them too late in the history of adventure

games to be able to turn back the wheel of time. The gist of the matter is

that the game simply happened to be produced at a transitional period in the

evolution of digital technologies, and certain conditional decisions taken at

the time have not aged all that well. On the positive side, I really like the

different ways in which Schafer plays around with the dialog tree; although

in general, it is structured fairly conventionally for a LucasArts game,

there are a few novel situations, making the procedure more comedic and more

realistic at the same time. Thus, at one point in the lengthy Saga of the Metal

Detector, you have to listen to a long, weepy rant from Carla the Security Guard

on her life problems, during which Manny has the option of making

sympathetic, sarcastic, or bored comments (Carla: "I was shy all the way through high school..." – Manny: "I was in detention all the way through

high school") — in real time, since the options constantly shift as Carla

speeds through her rant. You only really have to select any one option that

has to do with the Metal Detector to send things on their way, but I prefer

to wait out for as long as possible, because it is just so fun to hear Manny

interrupt the rant with rudely insensitive comments. At another point, in the Blue Casket

club — again, just for fun — Manny can get on the stage to deliver his own

beat poem, which, once again, you put together from options on the dialog

tree, randomized in packages of three or four at the same time to make you

choose the best selection (e.g. "Dig

this real. Can you see what I’m smelling? Is it you? Or am I you? I am not

dead. I crave disappointment. The cracks in my skull... lugubrious!").

Hilariously, if you then invite your friend Olivia onto the stage, she will

recite the exact same poem ("consider

it an homage", she retorts when Manny confronts her about it). Thus

do we get to fiddle around with the dialog tree in an amusing fashion and deliver a scathing parody on the

beat scene at the same time. For the little things like these, I might even

be able to forgive the tank controls... or, at least, the couple hours or so

of my life I’d wasted on going through my virtual pockets. As far as additional options are

concerned, the Remastered edition is pretty good on that, letting you tweak

video and audio options, play the game in fullscreen (with borders) or

widescreen (stretched) format, and turning on Director’s commentary where you

can hear Schafer and some of the other guys reminisce on all the good times

they had (honestly, I never had the patience to listen to all of it, but some

people really love those kinds of features). And, as with all the LucasArts

remasters, it is always possible to switch between the original and

remastered graphics at the toggle of a single key — although, as I have

already said, the difference is nowhere near as drastic as with earlier

games. You also do not get back the

complete original interface, since it is possible to use the mouse in both

modes. Overall, I can understand people who

complain that Grim Fandango «isn’t

all that fun to play», but I would

never regard that particular understanding of fun as a priority. The clunkiness of the interface is, in a way,

the equivalent of a great professor delivering his lecture with a piece of

chalk at the blackboard in the age of PowerPoint — if you want to deprive

yourself of a once-in-a-lifetime experience, nobody is forcing you. Grim Fandango is a magnificent game

that probably could have been designed even better than it was; but we won’t ever

be able to prove that. |

||||

|

Grim Fandango was

not the last adventure game ever made — it wasn’t even LucasArts’ last

adventure game (that /dis/honor belongs to the deeply inferior Escape From Monkey Island). Both Sierra

and LucasArts lingered on for a couple more years; and, of course, adventure

games would not exactly «die» in the 21st century, no more than progressive

rock «died» after 1975. But it is still hardly an accident that the title of Grim Fandango crops up with

predictable regularity in almost any critical or historical text on the

decline of puzzle-based adventure games — and I think that this has to do not

just with the chronology of its release, but with the fact that the game

itself plays out like a sort of long, bittersweet farewell; it has a certain feel

of finality to it, more so than any other LucasArts game I’ve ever played (and,

for what it’s worth, not a single Sierra title I ever played had that kind of

feel — though it is possible that Jane Jensen did drop us a veiled hint at

the end of the third and last Gabriel Knight

game). I don’t know if Tim Schafer saw a little bit of himself in Manny Calavera

(maybe I should have listened to

that Director’s Commentary, after all), but I certainly see a lot of those

idealistic, dream-driven game designers and writers in Manny: honest, noble,

hard-working guys who were in all this primarily for the art, rather than

just for the money, working toward making the world a more interesting,

intelligent, diverse place rather than a place run by all sorts of Don Copals,

Hector LeManses, and Domino Hurleys. The formally happy ending of the game,

with Manny and his love speeding away toward alleged blissful peace, changes

little — we know nothing about the Ninth Underworld, but we do know something

about the world that the protagonists leave behind, which is run by the same greed,

deception, and hypocrisy that we see around us in real life; and we know how

little hope there is of making it any better, even if you can achieve a

tactical victory now and again. Maybe Grim Fandango is not

the «best game ever made» — just how many titles would battle for that crown,

as if there were only one? — but one thing is for sure: it is the best game

ever made for the pleasure of Idealistic Cynics. Its levels of maturity have

been reached by a few (not many) titles in the following century, but never

transcended. Its synthesis of several different ages of human culture is not

only unique, but also meaningful — hinting at the homogeneous shittiness of

social relations everywhere, be it in ancient Mesoamerica or in 20th century Hollywood.

And its underlying moral lesson is, after all, quite simple — all you need to

survive in this shitty world is a good sense of humor, a loving partner you

can trust, and a sidekick who will always prefer a good sip of Lumbago Lemonade

over a corporate position. Much will depend, of course, on just how much you, the player, will be

able to identify with the character of Manny Calavera. To me, he is, along

with Gabriel Knight, one of the two greatest protagonists created in the

world of 20th century gaming, but this is because I find a lot in common

between those guys and myself; those who prefer to see their skies clearer,

or those who’d rather identify with revolutionaries (like the game’s Salvador

Limones), will not feel that much empathy

with the game itself, and ultimately might want to sentence it to death on

bogus pretexts, such as illogical puzzles or clunky interface. Yet something

tells me, deep down in my heart, that the more people there are in this world

capable of empathizing with Manny Calavera, the more chances it stands to postpone

the darkening of the Fifth Sun. |

||||