|

Half-Life |

|

|||

|

Studio: |

Valve |

|||

|

Designer(s): |

The

Valve Team |

|||

|

Part of series: |

Half-Life |

|||

|

Release: |

November 19, 1998 |

|||

|

Main credits: |

Storyline: Marc Laidlaw Music: Kelly Bailey |

|||

|

Useful links: |

Complete

playthrough, parts 1-7 (7 hours

10 mins.) |

|||

|

The sheer amount of text

written about Half-Life in the past

quarter century is probably comparable to the amount of studies written on

Shakespeare or Dostoyevsky; even if you have never played a single computer

game in your life, you may still have heard of Gordon Freeman and his

legendary crowbar — the late 20th century equivalent of Thor’s hammer and the

staff of Moses. This means that just another «oh look, Half-Life is one of the greatest games of all time, and here’s

why» review is hardly necessary, given how high it usually finds itself in

most cumulative ratings and how many people still play it on a regular basis

(though, admittedly, now that the fan-made Black Mesa remake is finally complete, interest in the original

has taken on a much more historically-colored flavor). But given that your

humble servant has a somewhat special, slightly atypical history of relations

with Valve’s classic, perhaps somebody might find it curious to take a look

at this personal angle, which would concentrate more on the storyline and

world-building aspects of Half-Life

than on its heavy action side. As you can probably

gather well enough by the introduction to St.

George’s Games, as well as the general selection of reviews on it, I am

not exactly «Mr. Action Guy». In my early gaming days, sometime in the late

Eighties, I did enjoy quite a bit of the arcade stuff — shooters,

platformers, everything from Alley Cat

to Digger and the

first-and-still-best Prince Of Persia

— but my attention was very quickly whisked away toward adventure games and

strategies, where you could immerse yourself in alternate realities at your

own leisurely pace, without being forced to take your game as a sports

activity. It might also have been a form of subconscious protest — the more

people around were getting hung up on «dumb» trigger-happy gorefests or

monotonously repetitive Tetris rituals, the more special you could feel when

identifying with Princess Rosella, Larry Laffer, or Guybrush Threepwood

instead of silly moustached plumbers or creepy blue-haired hedgehogs. The feeling that I’d

made the right choice in life grew even stronger in the days of early 3D,

when the world around went crazy for Doom

and Quake — games that, to me,

looked utterly moronic, not to mention exceedingly ugly with their crude,

blocky polygonal renders and monotonously generated backdrops. What kind of a

person could even prefer the likes of Doom

to something like Gabriel Knight or

Day Of The Tentacle? Or Sid Meier’s

Civilization, for that matter? The same

kind of person who’d rather watch Die

Hard than Goodfellas, no doubt.

I remember watching my younger brother at the height of his heavy addiction

to Quake and thinking, "oh my

God, I never expected that my explaining to him what Leisure Suit Larry Goes Looking For Love is all about at the

tender age of 8 years would eventually lead to this...". And then, unexpectedly,

it happened. Sometime around 1999, upon returning from a trip to the US, my

father brought me back a boxed game as a gift. Knowing how much of a Sierra

On-Line fan I was (well, we both were), and obviously knowing nothing about

Sierra’s very recent demise as a reliable producer of adventure games, he

simply saw an appetizing package with the Sierra logo and grabbed it as a

souvenir. Ironically, given that particular time window, he might as well

have wasted his money on something like King’s

Quest VIII, the most abominable «adventure game» ever released by the

studio. Instead, he inadvertently bought a first person shooter, and boy am I

glad he did. Naturally, I was

disappointed at first — a slightly more thorough look at the package (which

included both the original Half-Life

and the Opposing Force expansion)

clearly showed that the game was only published

by Sierra On-Line, while the actual developer was some bizarre Valve studio

I’d never even heard of; and all signs clearly showed that this was simply a

shoot ’em up experience, rather than a puzzle-based point-and-click title. I

do not even remember how much time it took me to even give it a try; visions

of myself getting caught up in a Doom-like

or, God forbid, Quake-like

environment were more embarrassing than visions of taking up a job in a

government office. Still, the package seemed rather expensive, and I really

hated the idea of serious money going to waste, even if the money was not

exactly my own, so after a while I braced myself and decided to give it a try

— after all, it wouldn’t exactly be like losing my virginity, since I did

have some experience with shooters and all. And who knows, maybe a

Sierra-published shooter would be something mildly special, after all?.. If this fairy-tale had a

truly happy ending, you would now be reading my confession about how playing Half-Life for the first time changed

my life forever, completely changing my perspective on first-person shooters,

and how I have since then become the happy father of... uh, I mean, the happy

owner of all the 5,000 Call Of Duty titles, let alone winning

all the prestigious awards for speedrunning and such. Unfortunately, the

truth is more boring: I am nowhere closer to admiring the mechanics of

first-person shooting (or third-person shooting, for that matter) today than

I was in 1999. I am, however, a

major admirer of the Half-Life

franchise, if seemingly for all the wrong reasons. And I do admit that once I

sat down and loaded up the game on that fateful day, I didn’t exactly get up

— or, at least, didn’t exactly think of much of anything else — until it was

completed, together with the expansion pack. The difference between Half-Life and all the first-person

shooters that came before it — actually, most of the action games, period,

that came before it — was clear as daylight. People usually pointed out the

obvious technical breakthroughs of Valve, such as the improved 3D

environments, the dazzling graphics, the integration of physical factors, the

shooting mechanics, the impressively advanced AI, but none of this mattered

as much to me as the emphasis that Valve placed on building up the overall

universe of Half-Life. All of the

action games I’d played up to this point, of course, had their own little

fantasy or sci-fi universes as well, but they were always clearly secondary

to the action. Even Doom actually

had a plot, but you wouldn’t know too much about it without reading the game

manual — the guys at id Software clearly thought that the kind of game where

you spend most of your time collecting ammo and gunning down demons needed

its pacing interrupted by «plot events» as much as a pornographic movie. The guys at Valve had a

different idea here: taking their cue rather from those kinds of porn

directors who want to not only show you people fucking, but also why they are fucking, they decided

that it was important not only to have you shooting, but also to have you

know why you were shooting — or,

for that matter, who you are supposed to be in the first place. To that

purpose, they actually hired a science fiction writer, Marc Laidlaw, to help

them create an actual world with an actual story that would be integrated

into the game itself, rather than read about in the accompanying

documentation; and it was largely Laidlaw’s achievement that, even if you do

not usually find Half-Life formally

classified as an «action adventure» game, it still feels very much like an

actual adventure — one day (and what a day!) in the life of Gordon Freeman,

an MIT graduate with a PhD in theoretical physics, though, as it happens,

most of the relevant physics on that particular day would be strictly

applied, like a crowbar to a zombie’s skull, for instance. Or, rather,

correction: one day in your life,

because the game takes very good care about convincing you to feel like an

unfortunate MIT graduate, caught up in the whirl of things beyond your

control. It would be futile to

deny that the massive commercial success of Half-Life was first and foremost due to the amazing (and I do not

throw that dirty word about too

liberally) breakthroughs on the technological front. People liked shooters,

and wanted their shooters to get better, and Half-Life took shooters to a whole new level, and people were

happy as a headcrab on a theoretical scientist’s head. But I do wonder what

the reception, particularly the critical

reception would have been if the game had been just a shooter, plunging you straightforwardly into the heat of

battle with weird alien creatures the same way Doom did. At the very least, its legend would have been less

resilient — after all, one could argue that the technical achievements of Half-Life have long since been

surpassed by other specimens of the genre (not least of all, Half-Life 2!), but the universe

created by Marc Laidlaw and the Valve team still retains a certain uniqueness

of its own. In other words, Half-Life is a classic example of a

«crossover» type of success, a game that can and will be appreciated both by

people who mostly just like to shoot things and those who, like myself, view

videogames as a vehicle for escapism and / or for fueling their imagination.

This, rather than its innovative approach to 3D imaging and physics modeling,

is Half-Life’s chief contribution

to the medium, and the only reason why I am writing this stuff in the first

place. |

||||

|

Content evaluation |

||||

|

As it often happens with videogames,

Marc Laidlaw’s story, written for Half-Life,

is nothing particularly special by itself. It incorporates several well-worn

tropes — a huge super-secret research base (Black Mesa), an innocent victim

of circumstances destined to become a hero against his wishes (Gordon

Freeman), and a ruthless alien invasion that cannot be stopped by an army,

but may be stopped by one man’s courage and intelligence (Lord Of The Rings, uh, I mean, Xen).

Boiled down to its essentials, it is not fundamentally different from

whatever one might read in the Doom

manual and seems clearly tailored to the needs and wishes of the action fan

and nobody else. Of course, the G-man is in the details,

and the details script the events of Half-Life

as a bona fide action movie — one that has a proper exposition, a dynamic

development with gradually built-up suspense and tension, and several

explosively climactic moments. Before you even have a chance to pick up a

weapon, you have a chance to be intrigued by the opening sequence — a long,

leisurely train ride through the enormous military and research complex of

Black Mesa, which could be situated in New Mexico or on Mars or in Wonderland

for all we care. The train ride takes up more than four minutes in my

playthrough — that is more than four minutes of unskippable passive action,

during which you can move inside the train to take in the 3D sights from all

directions, but can do absolutely nothing else. The script writers want you

to slowly, meticulously, thoughtfully suck in the universe in which you are

about to be stranded — not simply treat it as an original background for

shooting action, but become overwhelmed by its immenseness and technological

awesomeness: the endless tunnels, the huge open space vistas, the armies of

scientists and security guards, the intricate system of overhead and

underfoot railings, and, of course, the out-of-nowhere terrifyingly friendly

announcement voice of the Black Mesa Transit system ("missing a scheduled urinalysis or

radiation check is grounds for immediate termination..."). Nor is there any shooting to be done at

all in the first, introductory chapter ("Anomalous Materials"),

most of which will be spent running around corridors, chatting up fellow

scientists, putting on your defensive HEV suit, and getting ready for that

fateful experiment which will bring on "Unforeseen Consequences"

and change the world, or, at least, the market of 1st person shooters,

forever. In stark contrast with the imposing opening sequence (which is

almost as unsettling as the atmospherically comparable ride through the

totalitarian Combine Citadel in Half-Life

2), most of that chapter feels safe, almost homely and cozy, with not a

single sign of the chaos to come — in fact, I distinctly remember that after

a while, it almost made me feel like wanting

something to happen so that I could finally kick some ass. All of this

follows the same recipe as a quintessential catastrophe movie — the better

and safer things seem to be at the start, the sharper contrast they will form

with the moment when shit finally hits the fan. It’s perfect psychological

preparation. And when shit does hit the fan, Half-Life

begins to unfurl in more or less the same way as an action movie, while at

the same time respecting all the classic conventions of a multi-level action

game. There are several things such games are expected to have in order to be

satisfactory — such as gradually more and more complex challenges, new types

of obstacles, new enemies with higher defensive and offensive capacities,

occasional intermediate bosses, and, of course, a final climactic boss fight.

The problem is that, as a rule, a typical shooter would never explain to you

where all this shit comes from and how the heck does it even function —

because you were not offered a wholesome universe, you were offered a bunch

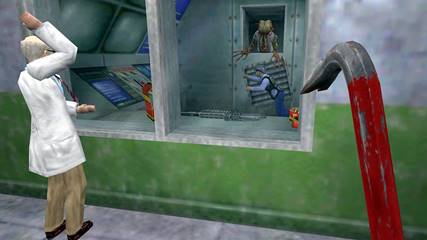

of fun challenges to prove your worth at pushing buttons. This is not how Half-Life operates at all. As the experiment concludes in disaster

and you find yourself as one of the few survivors, all thanks to your HEV

suit (and quite a bit of luck), the alien invasion begins, and it all feels

quite logical. First comes a wave of headcrabs, nasty little buggers who can

jump farther than cheetahs and have a bad habit of attaching themselves to

the heads of your co-workers, turning them into mutated zombies. Next, in

smaller waves, come far more brutal enemies — the acid-spitting «bullsquids»,

the ultrasound-shocking «houndeyes», and the semi-intelligent

electricity-flinging Vortigaunts. As the antagonists get deadlier with each

new level, you compensate for this by finding bigger and deadlier weapons —

some of them manufactured right here at Black Mesa, some «borrowed» from the

invading US marines, who have apparently been sent in by the government to

mop up the mess and silence everybody — both the aliens and the scientists. (This was a rather bold move, by the way, on

the part of Laidlaw and Co. — have Gordon Freeman actually mass-slaughter

authentic US army personnel by the dozens; they would not dare repeat this

motif when it came to Half-Life 2,

replacing the game’s human/oid/ enemies with the mutated and dehumanized

Combine soldiers, so as to spare you any unwanted remorse). The alien enemies aren’t just there

because they are supposed to be there; they materialize through a multitude

of briefly opening and closing portals, sometimes right in your face or (what

is worse) behind your back. The soldiers are carried to the base on military

choppers, and behave as realistically as possible — going to cover, trying to

encircle you, throwing grenades, limping and clutching their guts when they

get hit, sending out radio calls to their buddies. Weapons are found on

bodies of your human and alien enemies, in storage lockers, or acquired from

scientists, rather than just lying around randomly. And then, of course,

there is dialog — sparse, for sure, but enough to make the relatively generic

sprites running around you seem a bit more like real people. While your

original task may simply be to try and escape Black Mesa to safety,

gradually, bit by bit, you gather extra story details from the scientists,

ultimately learning that there will be no end to the catastrophe until you

yourself teleport to Xen and get rid of the Big Baddie holding the rift. The «plot» and the action actually

complement each other to a tee. Events that unfurl around you rarely impede

the tense pacing of the game — or, if they do, it is to provide you a few

necessary minutes to catch your breath and regroup before heading into an

even bigger mess (like the conversation and restocking sequence at the Lambda

Complex, right before launching the Xen teleporter). At the same time, all

the carnage feels as if it has a serious, significant purpose — most of the

time, you really feel as if lives aplenty, let alone the salvation of

humanity as a whole, are dependent on your success, to the extent that

whenever I died, I felt pangs of shame, as if Gordon Freeman really let mankind down by missing

that one last platform by an inch and plunging down to his death in a puddle

of radioactive sludge. And the presence of the sinister G-man, seemingly

stalking you wherever you go without revealing his identity or purpose, adds

an extra element of mystery and intrigue which, much to the writers’ honor,

is not at all lifted at the end of the game (though «honor» might be too

strong a word — it is more likely that Laidlaw himself still has no idea of

what it is that the G-man is supposed to represent, even after Half-Life 2 and all these years of fan

speculation). Corresponding to the traditional

«levels» of action games, Half-Life

is divided into chapters, each covering a particular map segment and usually

centered around one particular issue. These chapters gradually gain in

length, difficulty, and intensity, each one typically introducing a new kind

(or several new kinds) of enemies and weapons, being qualitatively rather

than quantitatively different from each other. To keep things even closer to

the feel of an action movie, there is a climactic «reboot» in the middle of

the game when Freeman is captured, deprived of all his weapons, and dumped

into a trash compactor — thus starting the «Residue Processing» chapter,

during which you have to get back some of the weapons and engage in a lot of

platform jumping (I actually hate playing that chapter, but I admit it is

there for a purpose). Then the game once again speeds up and intensifies,

culminating in «Surface Tension», a lengthy, detailed battle with everyone

and everything possible in the open air of the Black Mesa mountains. Finally,

there are the chapters that take place on Xen, the homeworld of the baddies,

which many players disliked for being underdeveloped compared to the rest of

the game, but I always regarded them as sort of an extended epilogue anyway —

this game is all about the Black Mesa experience, if you ask me. Almost two decades later, when fans

began work on the Black Mesa remake

of the game, they got all this ideology just right, never once

underestimating the power of surrounding events and dialog — in fact, the

opening chapter was drastically extended, with lots of extra funny details

thrown in. But what the sprawling, expansive Black Mesa did for the smaller-scale Half-Life, that smaller scale Half-Life

was doing in 1998 for the entire universe of action games, creating a new

medium which could finally merge the values of those who preferred playing

games «for the story» and those who would rather do it «for the adrenaline

rush». It was a merger that worked for me, doing something that Doom could never do — that is,

convincing me that at least some

action games could provide an immersive effect comparable to that of classic

adventure titles. Turns out, all you really have to do is provide a bit of

context... well, provide it the right way, that is. And which way is the

right one? Well, this is what the next few sections will be all about. |

||||

|

Action games in the early days were

usually brutal to players. Where adventure games could easily lead you to

dead ends and pointless demises, forcing the players to curse their way all through

the sixth or seventh replay of the same lengthy sequence, action games liked

to punish you fair and square, inheriting this brutality from the era of

arcade machines, whose chief purpose was to milk the player’s purse rather

than stroke the player’s ego. If you complained about the tremendous

difficulty of something like Mortal

Kombat, somebody around would always tell you to suck it up and practice

(i.e. spend hours upon hours of your precious time to get better at something

that would become obsolete in one year). Of course, some people were (and

still are) naturals when it came to conquering the controller and juggling

the joystick, but that made things even worse for those of us who weren’t.

Why bother at all, wasting hours on end trying to beat a certain game when

your dorky next door neighbour (who probably hasn’t read a single book in his

life) can beat it in ten minutes? And this, too, is where the design of Half-Life really struck me as quite

amazing in its time. Half-Life was

not exactly the simplest game to beat, featuring easily the most advanced

enemy AI to date — which, admittedly, was still not that advanced (glitches and laughable decisions taken by the

marines, such as running into their own grenades or getting stuck on corners,

were fairly common), but for the first time you had the odd feeling that you

were really fighting for your life with real people, made of (digital) flesh

and blood. Every now and then, you had to combine strategic and tactical

thinking with basic keyboard dexterity, knowing when to run and when to hide,

when to blast away and when to use stealth, which weapon to use on which

enemy, etc. Going all gung-ho on the alien invaders or your own compatriots

was possible, but would more often result in a swift death than an adrenaline

rush of Rambo-style invincibility. Yet this was precisely why Half-Life offered a friendly hand to

all those players who viewed action games with wary caution. Yes, it is a

game that cannot be beat without quite a lot of shooting; but even the most

intense, fire-heavy sequences could be carried off slowly, carefully,

thoughtfully. Instead of rushing the enemies with everything you got, you

could creep up on them from behind the corner, taking them out with a grenade

or explosive satchel when they least expected it. Or you could lure them around that corner, setting

up an easy advantage where they could be quickly headshot without putting up

much of a resistance — or even setting up a trip mine to achieve an even more

clean victory. The game’s 3D structure could be used to tremendous advantage

as long as you were careful enough to choose the right angle. Out of serious

ammo, with a couple powerful automatic turrets blocking your way? Creep up on

them from the correct direction and pistol the shit out of their tripod legs.

An enormous alien grunt policing the corridor? Wait until he turns his back

to you and put a crossbow bolt in that huge hive-hand of his. Above all,

simply use your head. Half-Life is

a game that has very, very few dead ends. If you are really desperate, the game features several difficulty levels,

ranging from «easy» to «hard», but not including anything like «nightmare» or

«deathmatch» — simply because, due to the very nature of the game, such

levels would not have made much sense, because they usually require superb

dexterity with the controls, whereas Half-Life

is so much more about strategic thinking than dexterity. Most of the times I

played the game, I did it on «hard» precisely because this setting forced me

to think creatively — on «easy», you could simply smash through the enemy,

but on «hard», where the same approach would lead to extra damage and

premature demise, you ended up thinking more about the environment, such as

taking note of the position of each and every explosive barrel that could

take your enemy out quicker than any of your guns. In the end, I got so good

that I could complete the game without taking any damage at all — not a

single hitpoint! — although that was also a bit of an extreme, since such an

approach required way too much stealth, bordering on tediousness. Although most of the physics-related

breakthroughs for Valve would come later, with the arrival of Half-Life 2, the original game was

already capable of giving you a feeling of being a real person in a real,

gravity-ruled universe, and not only when you were plummeting down from a

rocky height with a convincing crrrrunch!

at the bottom. Quite a bit of the game’s challenges are based on

platform-jumping, something that I typically hate, but, once again, this was

usually a matter of careful planning and calculation rather than nimbleness

of fingers (which, should I add, rather beneficially distinguishes Half-Life from Black Mesa, which did pander to more modern standards of action

games and introduced a few breakneck tempo sequences that pissed the hell out

of me). Like in real life, where you would rarely take 3–4 jumps across gaps

in a row without taking a break and carefully lining yourself up, you can

always take your time in Half-Life

as well. And if you did fall to your death — the game would simply give you a

chance to try again, from the very same spot, no need to reload or anything

(besides, the quick-saving mechanism was super-easy to use). In other words, Half-Life was simply the

perfect action game for action game haters — luring you in both with its

involving storyline and with its mercyful attitude towards those who were

into it for the fun, rather than the tough challenge. Even the final boss

battle with the Nihilanth, the annoying overgrown foetus in control of the

alien invasion, was more of a flashy spectacle than a true challenge — if you

got too nervous or overworked, you could always hide behind one of those

pointed spikes and have yourself a relaxed cigarette break, while all of the

bad guy’s projectiles would just break up against the spike. Which does not

mean that defeating the Nihilanth was not a challenge, far from it: it was

simply a challenge that you could accept on your own terms. You decide how you want to run this

game, not vice versa. |

||||

|

Yes indeed. From the opening shots of

the game, as your train emerges out of complete darkness to the

friendly-chilly sounds of "good

morning, and welcome to the Black Mesa transit system", Half-Life prides itself on its

atmospheric qualities. For sure, elaborate multi-level objects were nothing

new to computer gaming by 1998, but arguably nothing up to that point could

look as monumentally impressive as the Black Mesa Complex. It rolled out

before your eyes in a huge, uninterrupted, scrolling 3D sequence, with its

lengthy corridors, huge halls, odd devices, robots, conveyers, and sinister

green-glowing radioactive sludge — to be experienced, revered, overwhelmed by

on its own, not just as a setting for some upcoming heavy action. In a way,

it is the Black Mesa Complex itself, rather than the invading aliens or the

mopping-up soldiers, that functions as your chief enemy: a giant, depressing,

dangerous mechanical monster which is as much of a threat to your opponents

as to yourself (remember all those poor headcrabs, drowned in sludge or

squished between blades and pistons?). Escaping this suffocating monstrosity

clearly becomes a priority, and the game designers were certainly aware of

that, using this desire to their own advantage. The very first time you

actually get to see some blue skies is in the "We’ve Got Hostiles" chapter, where, after a few battles with

the newly arrived marines, you finally emerge into an open space — only to

see it, to your utmost despair, choking with soldiers and helicopters,

leaving you no choice but to quickly dash across the landing pad and dive

back into the bowels of Black Mesa. I still remember that desperate feeling (oh no, not the vents again!) quite

vividly, as well as the "Surface

Tension" chapter, which really went out of its way to prove to you

just how much safer it could be below ground than above it. Eventually you

have little choice but to adapt, or, at least, make some psychological

distinction between the «seedy» areas of the complex (vents, sewers,

machinery compartments) and the «clean» ones (office departments and

laboratories), even if in terms of actual danger there is no clear preference

between the two. While, obviously, nothing like Black Mesa

exists in real life (the Large Hadron Collider and Los Alamos National

Laboratory are about the scope of your school chemistry lab next to Black

Mesa), the facility looks so vivid that it can easily awaken all your hidden

technophobe feelings — or, pending that, set you on the philosophical train

of thought about the complicated relations between man and machines, man and

science, or, at the very least, taxpayers and government research grants

("well, there goes our grant money!"

some of the horrified gentlemen in lab coats are heard saying after the

catastrophe). Later, Half-Life 2

would try to repeat this mix of awe and terror with its depiction of the

Combine Citadel, but that would be an imaginary alien construction — Black

Mesa, for all of its absurd hyperbole, looks like a fully human creation,

simply blown up in scope, and this makes for a very special feel of disgust. In the aftermath of the Resonance

Cascade, Black Mesa becomes a place of attraction for all sorts of living

beings — aliens prowling its corridors, scientists running around in

confusion and horror, security guards shooting their way out, US marines

killing everyone and everything in sight — and all of them are pictured

essentially as hostages of the complex. The aliens are confused by the

vastness of the place, roaming all over it without any clear strategy of

purpose, killing every human in their path more as a precaution for their own

safety than anything else. The scientists are utterly helpless, though some

of them can actually help you out

in return for protection (or you can just kill them yourself, pretending to

be crazy or something — yet another example of Video Game Cruelty that would

be cut out of Half-Life 2). The

security guards can offer their services as cannon fodder (but I remember

feeling especially proud each time I was able to guide a small bunch of

guards safe and sound to the end of one or another particular level). All of

these NPCs are extremely limited in terms of what they can do, but these

limited functions are so well distributed between different types of sprites

that it really makes you glad whenever you come across a generic friendly

face. Some of those security guards, encountered after long periods of

loneliness, made me want to cuddle them, let alone risk my life protecting

them (when it’s actually supposed to be vice versa). One of the most controversial aspects

of the game have always been the final chapters — which Freeman spends on

Xen, teleported there in order to fight his way, one-man army-style, through

to the Nihilanth and close the goddamn rift. The section has been described

as woefully underdeveloped and unsatisfactory; obviously it is extremely

short, when compared to the lengthy traverse of Black Mesa, and features way

too much platform jumping and too much Alien Controller shooting to allow us

to fully appreciate the weird alien wonders of a parallel universe. To

rectify that mistake, the creators of the Black

Mesa remake even took out several years to create a much larger, much

more diverse and challenging world of Xen — which I am not sure was entirely

the right thing to do. Perhaps the relatively short length of the original

sequences was due to budget and time limitations more than anything else, but

also, it must be remembered that Gordon Freeman’s mission to Xen was a purely

pragmatic one — not to admire the unimaginable, transcendently dangerous

beauty of the place, but to put an end to an imminent threat as soon as

possible: get in, assassinate, get out. Even so, I could never claim that

proper attention was not paid to constructing a special kind of atmosphere

for Xen. In stark contrast with the claustrophobic Black Mesa, most of the

action there takes place in the open air — which is so full to the brim of

life-threatening situations that you soon wish you were back in the relative

comfort and safety of the research complex, where it was at least almost

always possible to snuck into some remote corridor or empty lab for a moment

of respite. Xen is a place full of predatory forms of life — bullsquids

chasing after headcrabs, big green tentacles mopping up the ground, Alien

Controllers supervising the slave labor of Alien Grunts (Vortigaunts) — and

making any progress in that environment feels like an even more imposible,

more surrealistic task than surviving in Black Mesa. And while the game never

truly descends into the conventions of the classic horror genre (that element

would not be added to Valve games until the Ravenholm level in Half-Life 2), advancing into the

bowels of Xen, past the Shelob-inspired arachno-monstrosity of Gonarch, the

Big Mama Headcrab, and the pitch-dark tunnels of the Nihilanth fortress with

Alien Controllers swooping out at you from nowhere, does require a certain

element of courage. Speaking of courage, perhaps the single

finest atmospheric find of the game is the multi-limbed Tentacle Monster

mini-boss in the «Blast Pit»

chapter. The sequence where you have to sneak past this green beaky thing

through several levels of a giant silo is not just nerve-wrecking, it also

makes great use of 3D mechanics — you don’t even need any VR equipment to

literally feel the breath of the thing over your head as you crawl along the

ledges, knowing full well that one wrong move may earn you a peck-of-death

from the unseen above. Even when replaying the game for the fifth time or so,

I still catch myself dreading the moment when I have to brave that silo — not

because the enemy is particularly ugly (what’s so ugly about a huge sprout of

asparagus with a hornbill beak on one end?), or because the death sequence is

particularly gruesome (hey, so your skull just landed in front of you, what’s

the big deal?), but because, when you screw up, you do not even see your doom

coming — you sense it coming, you know it coming, and you don’t even

have time to say your prayers. It also briefly turns Half-Life into a stealth game, just as the «Residue Processing»

chapter turns it into a platform-jumper — just another reminder of all the

incredible diversity of in-game experience. |

||||

|

Technical features |

||||

|

Every time I encounter yet

another generic assessment of Half-Life

along the lines of "yeah, still a good game after all these years, but

the graphics, unfortunately, have not held up", it makes me feel a little

sad. As I already mentioned, Half-Life

was the first ever 3D game I saw that made me acknowledge the potential of

those engines — the first ever 3D game which looked, if not exactly

«beautiful», then at least «realistic». However, several years later Half-Life 2 would set a new, much

higher standard — and with that new standard, graphic quality of the original

Half-Life would be officially

demoted to the status of the Rickenbacker Frying Pan. But does this really

mean that, while the original Half-Life

still remains a «recommendable» experience, its graphics today can only be

«tolerated», rather than continue to be enjoyed for aesthetic purposes? I would not agree with such

an assessment. The one area where time has really taken its merciless toll on

Half-Life are the outside areas. In

1998, even the Valve wizards still lacked the graphic technologies to produce

convincing 3D renders of natural environments. The rocky craigs around Black

Mesa share the same textures as slabs of raw beef hung inside the facility’s

meat lockers; the sandy dunes look like dirty wrinkled bathroom curtains;

water surface is not transparent and gives the impression of dried mud rather

than liquid. (It all works somewhat better when you are in Xen — which is,

after all, an alien world, so theoretically it could look any way you would

imagine it to look, polygons and all; the totally harmless blood-red soup

that passes for its underwater pools, for instance, is an extremely

impressive concept). These are the textures that underwent the greatest

changes from the first game to the second — which is why, unsurprisingly, Half-Life 2 could allow you the

privilege of spending most of the game on the outside rather than the inside.

But this is also why in the original game you have to spend most of the time inside — and it is fairly likely

that, had graphic technologies been more evolved in 1998 than they were, we

would never have experienced Black Mesa in all its somber glory at all. Half-Life’s GoldSrc engine, developed by Valve, was in fact a heavily

modified version of id Software’s Quake

engine, and you can certainly see a lot in common between the two games — but

mainly in mechanic terms. Unlike the interiors of Quake, the interiors of Black Mesa do not feel assembled from a limited number of polygonal building

blocks, even if, in fact, they are: instead of the generic brick layers, the

corridors and tunnels of Black Mesa consist of smoothly integrated panels

whose blurriness, as you zoom in and out with the camera, never seems as

off-putting as in previous 3D games. This is all the more important

considering that, unlike Doom and Quake, Half-Life is not a game that is naturally intended for

speedrunning — if you simply zip through Black Mesa’s empty spaces as fast as

possible, you are going to miss out on interesting details, unique examples

of objects and graffiti, occasional conversations, Easter eggs, and such. And

moving around slowly, taking in the environment, rarely results in visual

disgust (unless you find yourself in the open air). When it comes to character

models, I have probably been spoiled by the Half-Life High Definition Pack upgrade, which came out in 2001

together with the Blue Shift

expansion pack and introduced drastic changes to a lot of the NPCs — not only

increasing the number of polygons per character, but also changing their

looks (thus, the security guards no longer look like they never had a moment

of sleep since signing their Black Mesa contracts, and the zombiefied

scientists now have extra tendrils and gaping maws in their stomachs).

However, even back in 1998, as long as you did not pay too much attention to

shapes of fingers, the NPCs looked remarkably alive — what the Valve

magicians could not achieve with blocky polygons, they at least compensated for

by giving their characters funny facial features and hilarious gesticulation

to draw your attention away from the deficiencies. The alien models came in

amazing detail, making you stop in your tracks to wonder at things like a

headcrab’s toothy underbelly, or at the Grunt’s odd extra limb protruding

from his abdomen, or at the contrast between the huge head and the tiny hands

of an Alien Controller. The visual effects — lightning flashing out of a

Vortigaunt’s limbs, sound waves radiating around the Houndeye, stinging

insects flying out of the Grunt’s hivehand — were realistic and incredibly

diverse, as were the enemies themselves, designed in far more imaginative

ways than the traditional goblins and demons of Doom-style hostile universes; in fact, one could argue that the

body shapes, movement mechanics, and predatory strategies of Half-Life’s aliens were among the most

imaginative in sci-fi history (in this respect, Half-Life unquestionably beats Half-Life 2, where you spent most of the time battling humanoid

enemies, and most of the rest of the time battling the same aliens, e.g.

headcrabs and zombies, that you faced in Half-Life). In short, my answer to the

graphics criticism would be that Half-Life’s

visuals today are only as dated as you yourself would want to regard them —

in the sense that, although one look at them is sufficient to clearly place

the game in the late 1990s, you have no obligation to make the same

concessions as you would have to for the likes of Doom. Whenever I compare the visuals of the game with the

lovingly and respectfully crafted modern graphics of the Black Mesa remake, I never once catch myself subconsciously

wishing «how nice would it be if all the original textures and models were

replaced by these new shiny ones!»; I am simply content to have both sit side

by side and be able to go back to either depending on whether, at any

particular moment, I have more of a craving for complex and dazzling

perfection or for simple and immediate dangerous beauty, the same way I do

not have to choose one and only one when choosing between some Fifties’ rock

and roll classic and its polished remake by some Sixties’ or Seventies’ rock

band. And it is actually an open question — whether in 50 years’ time, when

the graphics of Black Mesa shall look

every bit as dated, people will be more frequently returning to it or to the

original game. |

||||

|

I have to confess a crime here: most of

the time I played Half-Life and Half-Life 2, I did so with the music

(but not the overall sound) turned off — so I do not have a deeply ingrained

memory of Kelly Bailey’s acclaimed electronic score for the game. The main

reason for this was not aesthetic, but circumstantial: the game is, after

all, a shooter, and loud music tracks can be very distracting when the surrounding ambient sounds actually

serve to indicate to you your enemies’ positions. Additionally, too many of

those soundtrack elements were aggressively fast and dynamic, almost spurring

you on to move as quickly as possible through your current location, whereas

I always preferred to take it slow and cautious. (This, by the way, is one

advantage that the original game, in my opinion, holds over the Black Mesa remake — the latter

re-crafts way too many sequences so that you have to act really fast or die,

particularly in the Xen area, whereas the original almost always let you set

your own pace). Anyway, no complaints about the musical

soundtrack as such — its shifts through distinct electronic sub-styles, from

New Age to industrial to trance to IDM are all in perfect agreement with the

environment, and the programming of the music follows a cool pattern as well:

lengthy sequences of relative quiet are usually followed by musical outbreaks

at critical moments in the game, e.g. when you are suddenly ambushed by a

pack of marines, or encounter a major boss, or get teleported away to a

completely new and dazzling environment, etc. I do not know if Half-Life innovated this strategy or

simply perfected it, but I do not know of any other 20th century games, anyway,

which would use it so effectively. But even without the music, the way Half-Life handled sound was marvelous.

Not only was there an immense number of sound effects implemented — the ways

they came up with all those weird alien vocalizations could probably fill a

book — but they worked hard on the surround effect, meaning that the sounds

grew louder upon approach to the source and could be panned from speaker to

speaker depending on your camera angle. This is something that is quite

naturally expected of all modern games, of course, and, again, was hardly

invented by Half-Life, but was not

implemented in such a flawless manner in any previous game I know. It was the

sound, in fact, that was responsible for the majority of the game’s

atmosphere — before turning each new corner, you would stop, hold your breath

and listen. Is there something like a soft pigeon-like purring ahead of you?

Get out the crowbar and prepare to whack a headcrab. Is that a bunch of gruff

radio chatter I hear? Must be one or two grunts patrolling that corridor. A

big, booming footfall? Better ready the grenade launcher, alien grunts have

just landed. And, of course, don’t get me started on the Green Tentacle

Monsters, whose manner of softly pecking their terrible beaks against the metallic

floor of the silo (on the inside) or the sand dunes (on the outside) is even

more unnerving than their constant demonic moanings and groanings. In addition to music and general sound

effects, Half-Life also had a small

voice cast, although it was largely unremarkable even when compared to Half-Life 2 — that game would go to

great lengths enriching your experience with memorable and colorful

characters, from Alyx Vance to the mad Father Grigori, whereas the original Half-Life is largely just populated

with nameless scientists, security guards, and marines, who diligently

deliver their lines in accordance with stereotypes (scientists are mostly

scared shitless; security guards are friendly, but not too bright pals who’d

like to hold your beer; and all the marines probably come from Texas or

something). One major exception, of course, is the famously mysterious G-Man,

who appears at the end of the game to deliver a short, but legendary speech —

he is voiced by otherwise not particularly well known Mike Shapiro (although

it sort of amuses me to learn that he had previously voiced the title

character in Al Lowe’s fairy tale Torin’s

Passage; believe me, it’s a loooooooong way from Torin to G-Man). Here,

again, the Valve principle of «let’s do it like everybody else does, but

let’s be a little different in everything we do» paid off pretty well — the

G-Man’s unique pattern of speech, suggesting everything from alien origins to

cybernetics to some extraordinary affliction, has long since passed into

voice acting legend. Only one truly important character in

the game has not been provided with a voice actor — in fact, his absolute

silence has since then become one of his defining characteristics. This is,

of course, you, as Gordon Freeman,

saviour of the universe as we know it, who is not only inaudible but also

largely invisible, apart from his crowbar-wielding, rocket-launching, or

snark-petting hands. (Unless you cheat your way into playing from a

third-person perspective, which is not something I would recommend: not only

is this mode super-glitchy, but Gordon Freeman looks ridiculously pathetic as

a superhero when you actually detach your spirit from his body). It is, in a

way, ironic how this «Freeman silence» ultimately became the source of all

sorts of Internet jokes and memes when Valve was doing absolutely nothing

here other than following well established conventions — people do not talk

in first-person shooters, they’re too busy shooting. This is, of course, precisely due to

the fact that Half-Life is so much

more than just a first person shooter — it is a story, and you are supposed to be an active part

of that story. At least in the introductory chapter, when Gordon makes his

way to the test chamber and communicates with all sorts of people along the way,

one would expect to hear him react — but note that the dialog is always

constructed in such a way that Freeman does not really need to say anything. He might be mute, as some have speculated,

or he might simply be a "man of

few words" (as Alyx Vance would refer to him in the sequel), but

ultimately he is just a victim of videogame trope circumstance and the Valve

team’s sense of sly and mystifying humor. Leave it to these guys to have

created easily the most memorable invisible videogame character of all time —

but what can you do? Sometimes a crowbar in a man’s hands does so much more

to define a man than anything else... |

||||

|

Interface And once again, God bless Valve for making

a shooter game that hardly even feels like a shooter game because of all the

minimalism. In most action games up until that time, you would usually have

some sort of status bar — with indicators of health, number of wasted /

remaining lives, ammo status, and whatever else the game designers thought to

include as extra parameters. Valve took a different path — it included NOTHING. Well, almost nothing. After you get into your HEV suit, it gives you a

tiny display of your vital statistics in the bottom left corner (one number

for health, one for armor) and an equally tiny one of the ammo status of your

currently wielded weapon in the bottom right corner. There is also a small

flashlight icon in the top right corner, usually inactive but indicating the

charge status of the flashlight when it’s on (I actually think this one was

pretty expendable). That’s it. Nothing else to clutter the screen. Just you

against the world. One of the many reasons why I typically

avoid modern shooters is the confusing clutter you often see on the screen —

status bars, health bars, enemy health bars, damage indicators, all sorts of

superfluous parameters that take your fun and transform it into annoying

sports metrics. Half-Life shows

that in order to have a fully immersive, exciting, adrenaline-filled

experience you need none of those bells and whistles. The opening tutorial,

in which you have to complete a training course under the guidance of a

helpful hologram, can be completed in ten minutes — five if you’re really

pressed for time — and is a textbook demonstration of the supremacy of

minimalism. You learn to move, sprint, jump, crouch, shoot your weapons,

recharge your health and ammo, and recruit security guards and scientists for

assistance. Out of this minimal arsenal of actions in reality springs out an

impressive number of actions, all of which shall be graduately introduced by

means of intelligent level progression and provide you with just as much fun

as the most complicated of the modern day shooters, if not more. It should probably be mentioned that,

outside of an occasional glitch or two, Half-Life

has always, from the very beginning, been of the smoothest running action

games I’d ever played. Although adjacent maps can (inevitably) take a bit of

time to load, running through each one at breakneck speed with a pack of

enemies at your heels never led to any freezes or drops in framerates — and

unlike so many games from that epoch which take a whole arsenal of tricks to

get running on modern PCs, Half-Life

has been simple and stable on any of the machines and operational systems

I’ve owned through the years (although, granted, this may have been due to

Valve diligently updating the code; they even made a separate port of the

game to their brand new Source engine for Half-Life

2, though I really only played that once and it wasn’t too hot — I think

they removed the option to dismember your buddies with the crowbar, and that

left my cruel ass feeling sad and disappointed). Furthermore, the «you’re following a

story» here ideology was enhanced by the clever handling of life-and-death

situations. Saving and restoring could be done momentarily with a quick save

/ quick load button at just about any point in the game, no «checkpoints» or

anything; even if you forgot to do that, there was a nice system of

background auto-saving which never slowed the game down or distracted your

attention. When you actually died, your auto-saves, at worst, rolled you back

just a few minutes ago, rather than having to restart the level from scratch.

All of that just brought back the point that you were not (at least, not

necessarily) playing Half-Life as a

game to Prove Yourself and Build Character; you were playing it so that you

could feel yourself in the shoes of a protagonist in a big sci-fi action

movie — and have fun with it. In fact, I was probably so spoiled with

the ease and naturalness of Half-Life’s

controls that I have since judged pretty much every other action game, or, in fact, any game containing

elements of action (such as RPGs) by the benchmark of Half-Life... and very few have really held up. If, for instance,

combat in the game features a health bar over your enemy and there is no way

to remove it, I count this as a deficiency — of course, it is always nice to

know the fighting condition of the opponent and approximately how many more

hours you have to chip away at his stamina, but it is even nicer to be able

to shut that off, since in real life you would hardly encounter a glowing red

indicator over the bad guy’s head. (Actually, Half-Life has certain special ways to show you that you have made

progress with some of the enemies — for instance, the Vortigaunts, when

seriously hurt, lose the capacity of discharging their electric bolts and run

away in fear, while the marines utter curses, cling on to their wounded guts,

and limp away to regroup. No signs of battle fatigue from the Alien Grunts,

though, ever — these guys are

obviously much more badass than their human counterparts). I won’t even mention all the limitless

possibilities that open up when you learn to properly handle the game’s

console, and / or make use of the hundreds of mods engineered by the

community in order to prolong and diversify your fun in the Half-Life universe — again, Half-Life was hardly the first game

that allowed to do this (Doom and Quake had already set the bar pretty

high in that respect), but as far as I know, it still remains a favorite for

all sorts of speedrunners, glitchploitators, and people who like digital

magic tricks in general. That is not my kind of thing at all (I always prefer

returning to the original universe in order to re-experience it and sniff out

more subtleties to content mods and fan fiction), but all I can say is that

any game that still has people modifying it and finding new ways of having

fun with it more than 20 years after the original release has certainly

contributed to the destruction of the myth about videogames being inherently

devoid of lasting value. And much of this has to do with the ease and

openness of Valve’s original interface. |

||||

|

Just as music is so commonly separated into «music for the mind» and

«music for the body», yet there are outstanding specimens of that form of art

that manage to combine both, so is Half-Life

that rare type of game which was able to bridge the gap between videogames

«for the fingers» and «for the soul». Rare? Well, maybe not that rare anymore, given the rise of

all sorts of action-adventure titles in the past quarter century, but where

would all those titles be without Half-Life?

Before that game, genre-melding largely took the form of initiatives like

«okay, let’s make them find this secret panel and guess the code in between

shooting everything that moves» (for action games) or «okay, let’s insert

this pointless bit of combat in between all the puzzle-solving» (for

adventure games). To come up with an experience that could goad a seasoned

adventurer into learning to shoot ’em up, or

a seasoned action gamer to actually get involved with and worry about an

actual storyline plot did not require actual «genius» as much as it required

lots and lots of hard designer work. How do we make the use of this weapon

intuitively obvious? How do we make this boss enemy a creature of unique

mythological properties, rather than just a generic bullet sponge? How do we

insert this plot-advancing detail without making the shooter fan lose

interest? How do we inject elements of mystery that will hold the adventure

fan glued to the action until the end of the game? How do we keep the

difficulty curve of each level smooth and even without becoming too

predictable?.. In

regard to all these questions and more, Half-Life

is like a proverbial textbook — a game that should be the natural source of

learning and inspiration for all future designers, although it already has a

major advantage over all of them by having been there first. The biggest

mistake anybody could make would be to interpret this lesson in an «I want to

make another game just like Half-Life!»

fashion, because if the Valve team thought that way, well, they’d simply come up with a Doom clone. Instead, what they thought was: «We want to make a

game like Doom, only we shall have

everything better than everything else in every possible way we can think

of». Take a quick look back at the different sections of this review — each

single one will mention one or more innovative elements, and each single one

of these elements was integrated into Half-Life

not just because it had to be «different» for the sake of difference, but

because the team was committed to not only making the best of contemporary

improvements in hardware and software technologies, but also making the best

of that one technology we are all endowed with, but often neglect — Common

Sense. This

is why, even if most of Half-Life’s

technological achievements have long since been overshadowed by further

technical progress, the game remains a more satisfying experience than so

many later ones — replaying it over and over again is like reliving a

particularly exuberant triumph of the benevolently creative human mind. No

other action game I’ve played or seen played comes truly close to replicating

that feeling for me — well, maybe with the exception of Half-Life 2, which was one of the major violations of the

«lightning never strikes twice» principle in the history of human

civilization. And this is coming from somebody who is still afraid that he

might have been loving this game for all the «wrong» reasons, at least next

to its regular army of speed-running, mod-crafting, Counter-Striking fans. |

||||