|

|

||||

|

Studio: |

Sierra

On-Line |

|||

|

Designer(s): |

Roberta

Williams |

|||

|

Part of series: |

Kingʼs

Quest |

|||

|

Release: |

May 10, 1984 (IBM PCjr) / May 31, 1984 (IBM PC) |

|||

|

Main credits: |

Programmers: Chris Iden, Ken MacNeil, Charles Tingley |

|||

|

Useful links: |

Complete playthrough (75 mins.) |

|||

|

Technically speaking, Kingʼs Quest was not the first game

made by Sierra On-Line, who already had a solid history of text-based

adventure games behind their belt by 1984. It was simply the first game where

all the major Sierra trademarks came together: colorful graphic interface, linear

(and occasionally choice-based) plotline advanced by puzzle solution, and, as

intangible as it may seem to some, that special «Sierra feel». And although

it does look old, due to the overall immersion factor, it is

the first Sierra game where even modern gamers might end up forgetting that they

are consciously involved in a «retro experience» — and just enjoy the thing

for the pure fun of it. The plot, as laid out by

Roberta Williams, is extremely simple, being almost entirely structured on

old English fairytales. As Sir Graham of the Kingdom of Daventry, an old

magical realm which is now in a state of decline, you are commissioned by

King Edward to find and reclaim three of the kingdomʼs long lost treasures — a magic mirror, a magic chest filled

with a never ending supply of moolah, and a magic shield that makes you

invincible. Your task is to scour the kingdom in search of these three

objects, performing various little sub-missions along the way. Do this right

and you become king; do this wrong and you have to start all over again...

and again... and again... The game was first released

for IBM PCjr in 1984, with the more common PC release coming just a few weeks

later. Most of its innovations stemmed from the introduction of the AGI

engine (Adventure Game Interpreter), a working environment that permitted for

relatively easy programming of game sequences with incorporated graphics and

sound capacities. AGI remained Sierraʼs primary working tool

until around 1988, when it was replaced by the technically superior SCI

engine. (However, amateur adventure games are still being regularly made with

AGI even today — many of these can be downloaded online at little or no cost,

with a small, but dedicated community carrying on the torch). |

||||

|

Content evaluation |

||||

|

Seeing as how Kingʼs Quest was the first game of its

kind, there isnʼt really much of a

plotline. In fact, I have to admit most of it was probably thrown together by

Roberta in 15 minutes or so. Very few things are invented: for

the most part, it is just a mishmash of popular English folk motives — goats

and trolls, gingerbread houses, the giant and the beanstalk, leprechauns and

fiddles, etc. etc. In her future games of the series, Roberta would learn how

to manipulate these motives with more originality, even adopting a slightly

post-modern touch on some issues. Here, though, the emphasis was quite clearly

on everything but the plot. We do not have the least idea

how the actual treasures came to be where Graham founds them, or how come

nobody found them before Graham, or how come Graham manages

to find them so easily. (Some of the prehistory of Daventry and its treasures

is explained in more details in the accompanying booklet, but even then there

are multiple loopholes and gaps). A particularly odd thing is

the idea of finding minor secondary treasures scattered all over the kingdom

as a way to boost your points, but little else — not only is this befuddling

per se (who the heck keeps dropping jewel pouches through the countryside?),

but there is nothing useful you can actually do with these

treasures (although in some places you can actually lose points

by using them in the wrong way). All of this just goes to show how new this

whole business really was at the time. |

||||

|

Generally, the puzzles are

quite simple, which is not bad, since the game clearly had young kids as one

of its primary target audiences. There are occasional odd lapses: for

instance, the puzzle of guessing the gnomeʼs name is quite definitely

unsolvable without serious hints, meaning that very, very few of the original

players could ever get to climb that beanstalk. (Fortunately, the situation

was remedied in the SCI remake years later). But for the most part the puzzles

conform to the standard scheme of «get object A in location B, use it on

object C in location D». One thing that Sierra had from the very start was

offering multiple solutions to the same puzzle, a nice move that added an

extra replayability bonus to the game. Here, though, for most puzzles there

is a «right» solution, where you win points, and a «wrong» one, where you can

get through the sequence but will lose points in the process — as opposed to «equal

value» multiple solutions in later games. Already in this very first

game we also see the downside of the general Sierra plan — mixing of puzzles

with occasional inane «quasi-arcade» sequences. For a reason that I have

never understood, Sierra developers thought it absolutely necessary to

include at least several «navigate the keyboard» gizmos in each and every one

of their games, which would almost certainly include at least one or two sets

of narrow stairs which have to be climbed by an agile alternation of the

Up/PgUp keys (thatʼs «up», obviously) and the

Down/PgDn keys (thatʼs «down», respectively).

In Quest For The Crown, the epitome of this plague is the already

mentioned «climb the beanstalk» puzzle, where you simply have to grope your

way up with no clues and endlessly restore your game — probably a big nag

back in 1984, when it actually took the machine some real time to bring back

your settings. I still have no clue as to how they came up with this strategy

— if the idea was to somehow appeal to lovers of the arcade style, the point

was, at all times, sorely missed, and from what I have read in retro-reviews

and fan memoirs, there were far more people hating this stylistic merger

rather than loving it. |

||||

|

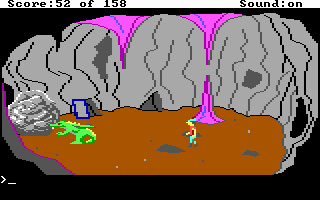

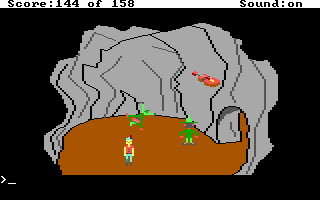

Being the first game in the

series and all, there isnʼt that much immersion in the colorful, but parsimonious world of

Daventry. The locations are few, the characters are even fewer and, worst of

all, there is too little interaction going on: most of the people you meet

either do not speak to you at all (preferring to chew you up on the spot) or

confine their information to one or two lines of text. Sierraʼs well-known attention to detail, so much lauded for their «classic»

period, is yet nowhere near in sight. The primary character, Sir Graham, is

not characterized by anything apart from fairy-tale clichés about

bravery and gallantry (for all his bravery, though, he does not even get to

fight anyone). And the whole thing rushes past you way too quickly in order

to establish a long-lasting relationship with this world. Still, there is no denying

that this is a world — relatively diverse, unpredictable,

and magical. You get several locations — lakes, meadows, hills — that are

there just for the sake of adding extra detail, and, like in most Sierra

games, you can spend time just wandering and exploring in a non-linear

fashion. It is not a particularly safe world, either, as you

will be stalked by evil wizards, witches, ogres, and wolves on many of the

screens, establishing the classic Kingʼs Quest contrast between «safe

and cuddly regions» and «dark and dangerous regions», albeit in a rather

haphazard manner. Thus, while the game cannot really be compared in terms of

mood setting to the ones that followed, it is still compatible with them in

spirit. |

||||

|

Technical features |

||||

|

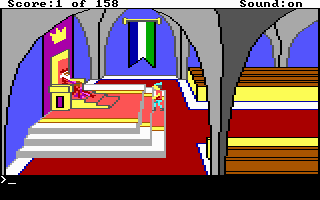

Most of Sierraʼs AGI games conformed to the highest graphical standards of the

times, painting as much and as best they could with EGAʼs 16 colors and low-level resolutions. As the first ball to get

rolling, Quest For The Crown, I would say, is slightly below

these standards — but only slightly. Perhaps the most significant difference

is the relative lack of care in painting the backgrounds: with most of the

attention directed simply towards getting the whole project realized, details

did not yet matter that much. So, you will see fewer trees,

bushes, houses, etc., than you would soon be getting used to. The ones

that are there, though, are done nicely: I very rarely

cringe at the sight of any inanimate object in the game. There are shadows,

horizon lines, brief contours on trees and rocks that try to emulate 3-D,

namely, everything to ensure you this is crude, but not "fake". One area where significant

progress had yet to be made are the character sprites. Grahamʼs mechanically moving figure, to tell the truth, is more reminiscent

of Pinocchio than a brave, gallant knight, and it is even worse with many of

the other characters. While Sierraʼs sprites truly did not

become «believable» until the SCI era, their elaboration was certainly

gradual, and already in the following few games the characters were more

intricately pixelated and their movements were more detailed and varied.

Here, it is a major flaw, because in terms of immersion, easily the most

important thing is to be able to identify yourself with the character you are

playing for, and it is pretty hard — if not impossible — to identify yourself

with a pair of walking matches in a blue cap, especially if the plotline says

you are poised to become no less than the king of Daventry. |

||||

|

Very little sound here,

apart from the clever encoding of ʽGreensleevesʼ into PC speaker format — one that probably ensured that for

most young players of the day, the tune is now forever associated with

Roberta Williams and her fantasy world. Sierraʼs budget was probably still

too tight for them to hire someone as resident composer, so most of the time

you will be playing in complete silence (for some people, this might not be

so bad, given the occasionally dubious quality of PC speaker music). However, there are already

signs that Sierra was not about to not make use of the

computerʼs ability to produce sonic waves, most

obviously in the form of a few sound effects that are quite cleverly

scattered around to punctuate significant moments. The spookiest one is the

six-note «danger» signal which is thrust at you from nowhere whenever some

baddie starts crossing your path — given the shrillness of the speaker and

the complete unpredictability of the enemyʼs appearance (they only

appear on certain screens, but it is always at random whether they do appear

and, if yes, when), I remember them giving me quite a few jump

starts. There are also some funny effects, like the one from falling down

stairs or trees (or, God help me, that beanstalk!), or while

dealing with the side effects of falling. That is all there is to say. |

||||

|

Interface Here, too, we have a

revolutionary start which, however, was to be greatly improved already soon

afterwards. The classic Sierra parser drives most of the game, but at this

moment, it is still very much underdeveloped, understanding only a few basic

words and nouns and not letting you experiment. The greatest downside, which

was corrected already in the second game, is that there is no command to get

a general description of the location — simply typing in ʽlookʼ will get you a retort of «You

need to be more specific». This is particularly harsh when you find yourself

dealing with objects that are hard to identify because of the poor state of

the graphics — not having a general description in which they could be

included, you will just have to guess what they are. (Hint: Whenever in

doubt, type ʽlook at the roomʼ rather than simply ʽlookʼ, probably a commonplace for text adventure game veterans in

1984). The interface also includes

a few shortcuts, such as the «swim» and «duck» options (the latter is sort of

superfluous — you only need it once over the course of the entire game), with

the rest more or less carried over into subsequent games. |

||||

|

Todayʼs

average gamers would be hard pressed to imagine all the hullabaloo caused by

the release of Quest For The Crown in 1984, but a good

advice would be to compare it not with what came after it,

of course, but with what was before, even with Sierraʼs

own titles like Mystery House. The thrill of seeing text

adventure game style combined with actually seeing what was

going on must have been tremendous. And let us not forget: everything that

made up the basics of Sierra gaming for a decade and a half from then on is

already here, in some form or other. Everything would be improved upon, of

course, but there would not really come around a visionary breakthrough that

would elevate adventure gaming on to a qualitatively different level — with

the possible exception of speech audio introduction, maybe. So it is hardly

possible to overestimate the historical importance of the game. Its level of enjoyability is a different thing altogether. It is

certainly too crude to be considered a classic along the same lines as,

say, Kingʼs Quest IV or VI. But if one treats the Sierra universe

as a cohesive and continuing entity, then, of course, Quest For The

Crown is inexpendable as the introduction to the

world of Daventry. It stands much better as part of the series than all on

its own, but as part of the series, it does a good job of setting the

scene. And while both Sierra’s own SCI remake of the game in 1990 and AGD

Interactive’s VGA remake in 2001 are obviously more easily playable on modern

computers due to improvements in the graphic quality and gameplay interface,

I think that for the wholesomeness of the experience you should still go back

to the original version — it is just so pure, innocent, and minimalistic that

forcing it into the age of puberty might take away its best qualities without

necessarily making it feel more advanced and satisfactory. |

||||