|

|

|||||

|

Studio: |

Sierra

On-Line |

||||

|

Designer(s): |

Roberta

Williams |

||||

|

Part of series: |

Kingʼs

Quest |

||||

|

Release: |

May 1985 |

||||

|

Main credits: |

Development

System: Jeff Stephenson, Chris Iden,

Robert E. Heitman Game

Logic: Ken Williams, Sol Ackerman,

Chris Iden, Scott Murphy, Dale Carson Graphics:

Doug MacNeill, Mark Crowe; Music: Al Lowe |

||||

|

Useful links: |

Playthrough pt. 1 (54 mins.) |

Playthrough pt. 2 (38 mins.) |

|||

|

It is hard to say whether Roberta Williamsʼ vision of the whole Kingʼs Quest franchise was already in place when the

first game was being sketched, or if it was only with the huge success of the

original game that she started to perceive this as merely the first element

in something really big. The fact is that Kingʼs Quest II had a point to make — we are here, and we are not going

away, and from this moment on we are only going to get bigger and bigger. If

the first game merely made a hint at a gaming universe to come, the second

game established that universe as a matter of fact. After all, you cannot

create a universe out of a single unit. It takes at least two to tango. Not that back in 1985 Sierra people were already drowning in creative

ideas. In many respects, Kingʼs Quest II is a carbon copy of its predecessor. Once again, you play

as King Graham, itʼs just that

now your task is not to get yourself a kingdom (that already having been

procured — you are called King now,

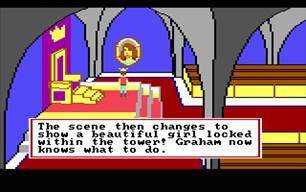

after all), but to get yourself a wife. So, after experiencing the obligatory

damsel-in-distress vision in your Magic Mirror, you are obliged to travel to

the faraway land of Kolyma, where you will have to locate the entrance to the

magic world in which the lady is imprisoned behind three closed doors. (Fun

side note: I sure would like to try some of the mushrooms Roberta Williams

was on to have named her fictional realm Kolyma

— yeah, maybe the name has a nice ring to it, but most people should know

that it is really the name of the barren sub-Arctic region famous primarily

for hosting multiple GULAG prison camps under Stalinʼs regime. Which means that a phrase like ʽKing Grahamʼs adventures in Kolymaʼ must have made many a Russian gamer laugh his ass off when the Kingʼs Quest series first got to Russia). Anyway,

about 90% of the game is spent in search of the keys, and then just a couple

more puzzles await you on your direct way to your future brideʼs heart. Popular consensus today

seems to be that there were too few departures from the first game in order

for anyone to consider this one an equal classic. Yet in many ways, too, I

would say that Kingʼs Quest II is generally

more playable and even accessible to the gamer of today than its predecessor;

where Quest for the Crown certainly

gains in historical importance, Romancing

the Throne is arguably closer to my intuitive understanding of what a regular Sierra On-Line game should

look like. In any case, Williamsʼ alleged lack of

imagination for this sequel certainly did not hurt the sales — the game was as

much of a hit as its predecessor, even more so, maybe, and it is actually to

Sierraʼs credit that its commercial success did not

prevent the creative minds behind the company from exploring further and

further ideas. |

|||||

|

Content evaluation |

|||||

|

In general terms, the plot

is almost exactly the same as it was before: get closer to your goal by

successively uncovering the locations of three magical objects (this time,

the three keys to the door that will lead you out of Kolyma). You play as the

same Graham character of the previous game, meet and interact with multiple

characters in very similar ways, evade many of the same dangers (sometimes,

in fact, absolutely the same – the mischievous dwarf and the evil sorcerer,

for instance, have been transplanted from Kingʼs Quest I fully intact, as if their main goal in life were stalking King

Graham wherever he went), and die in many of the same ways. Likewise, you

still get loopholes and unexplained events a-plenty: you might be able to

find the three keys, for sure, but you shall never for the life of you be

able to understand why you were so lucky as to find them in their respective

locations. And yet, at the same time,

the plot certainly feels much more elaborate than first time around. For

starters, it is longer — the game now features even more twists, turns, and

minor subplots, and does not convey the feeling of an instantaneous toss-off.

More length involves more chaos control, and thus it is also more linear:

certain events cannot happen until you have triggered them, so that it is

technically impossible for you to get the key to the second door before the

first one. In fact, this is the first Sierra game where you have to directly

live out the golden rule: never give up on a location for good, but keep coming

back after you have scored a few points elsewhere. Second, it is much more

bizarre. In fact, it is so bizarre that this, not Kingʼs Quest I, should be considered the

true start of Sierraʼs post-modern flavour. You

would have to be pretty deranged to put King Neptune, Count Dracula, an

Eastern-type genie, and Little Red Riding Hood in the exact same game -

granted, they do not interact with each other, but still, their sort of

peaceful co-existence within a few screensʼ walk from one another is

something completely unexpected at the time, in computer games or any other

type of media, for that matter. (I guess you could find some of that mythological

mish-mash in comic books, but certainly not ones intended for large

audiences). Again, very few lines of

the plot can be said to have been invented — mostly, it is a grab-bag of

everything in sight — but with the grab-bag being so unpredictable, mixing up

Western and Eastern folklore, Gothic literature, and Greek mythology, itʼs probably the best solution that Sierra could offer at that

moment. (In fact, come to think of it, very few of Sierraʼs plots have ever been radically original - and I do not blame

them for it). |

|||||

|

Just like in Kingʼs Quest I, the puzzles are rarely

anything to write home about: most of the "tight spots" are being

overcome by finding an object in a different location and using it on the

troublemaker. So the most frequent verbs that you will be using here are

"take" and "give". However, for many of the puzzles, as

before, alternate solutions are possible – one "wrong", causing you

to lose points, and one "right", making you gain them – and

frequently, the "alternate" solution features a non-trivial move,

forcing the player to find a less common command for the parser. There are

also next to none of those "crazy things you have to do" which

Sierra game players frequently complain about. If there is something

illogical and incomprehensible, it is mostly the locations in which you find

the objects, but not their functions, which are very clearly defined. The game also introduces

the concept of the red herring – if in Quest

for the Crown all of the objects you picked either served an important

purpose or at least were there to award you extra points, here you will, from

time to time, fall upon things which can be picked up and looked at (quite

nice pictures, too), but have no use whatsoever – except as to serve as

frustrated objects in your verbal constructions when you are stuck and try

out all kinds of desperate solutions. So, if ever you discover someone who

can be smothered with the pillow from Count Draculaʼs coffin, please let me be the first to know. In the meantime, Iʼm not complaining – life as we know it would be far more boring

without its share of red herrings. The gameʼs great advantage is the near-complete lack of

"arcade" sequences; at most, you get to navigate a couple

relatively easy stairs, and at one point, there is a short maze of poisoned

thorns that you have to walk around – but can as well avoid through a much

easier way (in fact, one that will earn you more points). This earns it extra

respectability points from me – unfortunately, for the first and last time.

The biggest disadvantage, then, is the introduction of dead end situations,

ones where you play "past the point of no return" without having

done what needed to be done, and having to replay a large part of the game as

a consequence. That said, today, when it takes less than half an hour to sit

through the entire game, this is less of a problem, and there is only one

such situation in the entire game, anyway (hint: pay proper attention to

crossing that old rickety bridge!). |

|||||

|

It is hardly to be doubted

that a lot more care was given this time to the issue of

atmosphere and believability. In the previous game, Daventry was represented

by a "checkered" map of 6x8 = 48 squares, which was practically the

equal of Kolyma (7x7 = 49 squares), but the major difference was in that

Daventry was monotonous, not to mention oddly rounded – whenever

you went straight ahead, you would eventually end up in the same space, as if

stranded on an asteroid straight out of Le Petit Prince. Kolyma,

on the other hand, is only rounded vertically; to the east and west, your

progress is respectively hindered by unpassable mountains and uncrossable

(though very much drownable) sea, and this alone means that you get a set of

seriously different landscapes. Like before, the terrain is

divided into "friendly" and "hostile" territory. The

latter is no longer limited to isolated enemy-dominated screens; instead,

what you get is vast areas constituting the "turf" of the gameʼs baddies – the cannibalistic witch, the cleptomanic dwarf, and

the sorcerer with a frog fixation. Except for the witch, who prefers to prowl

on deceivingly innocent-looking territory, the other two dominate the

"wilder" areas of Kolyma, which are thus better avoided unless you

are guarded with a protective spell. There is also a creepy poisonous lake

which should be avoided at all costs. It is a bit unclear, of course, how

Little Red Riding Hood is ever able to survive long enough, stuck in between

the witch and the sorcerer, but do not expect to get answers to all the

questions. Particular kudos, however,

go to the depiction of Draculaʼs castle – reflecting

Robertaʼs double-sided passion for fantasy and horror.

The whole segment reflects the most up-to-date, state-of-the-art computer

horror for 1985: ghosts, rats, bats a-plenty and an unseen evil presence

lurking around the dilapidated castle. Even I, having played this for the

first time long after 1985, was quite happy to get out of

that castle and back into the sunlight again... Finally, Romancing

the Throne is the first Sierra game where the player really starts

feeling him/herself part of this bigger-than-life thing, the "Sierra

Universe". Most of this feeling, of course, comes here in the form of

unconcealed promotion of Sierraʼs other products, in this

case, the upcoming releases of Space Quest and Kingʼs Quest III. But they are quite cleverly done, with humor and innocence,

and the idea of concealing a commercial plug for Space Quest in

a hole in the rock (where you would rather expect to find another piece of

hidden jewelry) gotta rank with some of the companyʼs most creative ideas ever. In addition, we start

getting Sierraʼs fabulous Easter eggs: do not

miss the Batmobile itself, coming out of a perfectly unexpected location! |

|||||

|

Technical features |

|||||

|

Since the game features

multiple locations, each associated with a particular atmosphere, it is

evident that extra care and work had to be applied, and the result is a

phantasmagoric smorgasbord that is utterly over the top in places, nowhere

more so than in the "enchanted isle" area where you arrive at the

end of the game to get the gal. There, you have rose coloured skies, purple

oceans, deep blue and yellow soil and light blue bushes in true Yellow

Submarine fashion. The effect still looks dazzling to me. It would

have been real gross to play all the game in that setting, but a few screens

worth of such psychedelic bliss must have been unforgettable to players at

the time. Other notable areas include the bottom of the ocean, littered with

all kinds of useless, but pretty artefacts, and, of course, Draculaʼs castle, with its cracked walls, ghosts, and rats. However, in

many other respects the gameʼs locations just seem like

leftovers from the drawing sessions for Kingʼs Quest I. I, for one, would not have expected King

Graham to take the trouble of journeying all that way to Kolyma only to find

himself in an ecological twin sister to Daventry. A major addition in terms

of realism are the graphic effects, although here they are still mostly

confined to brief instances of splashing water and jumping fish in the

"ocean" area. Characters are also livelier, with the mermaid

flapping its tail, the magic horse spreading its wings, and the poisonous

snake thrusting its head back and forth. On the general sprite level, though,

little has changed: Graham is still a pair of moving matches, and whenever

the characters turn their face to you, they look like pale imitations of

their Lego copies. A notable exception is the sprite of Count Dracula, with

its pale face and bloody lips – maybe it is because he is always seen in

profile. |

|||||

|

If the original game

featured pretty little in terms of music/sound, Kingʼs Quest II, the first Sierra game with a separate credit for ʽmusicʼ (going to Al Lowe),

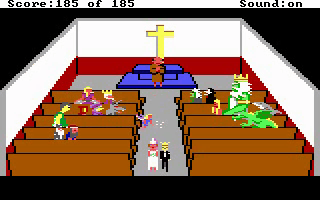

already has several distinct themes — in addition to ʽGreensleevesʼ, you have several merry

tunes that draw you in towards the end of the game (the ʽMeeting Valaniceʼ theme and the wedding

theme). This is still not much, but then again, with the limited abilities of

the PC speaker, not much is needed. What is needed

is more sound effects to liven up the general proceedings, and some are done

very nicely, like the spooky ooh-oohing of ghosts in front of Draculaʼs castle, or the roar of the lion guarding the tower, or the

chirping of the bird locked in Hagathaʼs cage. Of course, there is

nothing particularly realistic about these sounds, but remember, we are

talking about an era when Sound Blaster was still something associated with

little other than Star Wars. Still other effects, like the

"danger signal", are simply carried over from the previous game. |

|||||

|

Interface The parser has been vastly

enhanced. You are now able to type ʽlookʼ and get a general description of the area without having to

guess the true nature of its objects. Also, since the game is bigger and

includes more types of activities and objects, the parser now obviously

recognizes many more verbs and nouns than it used to. Expletives and suchlike

are still not incorporated, but you can now spend a lot of

time on each screen trying to figure out the various ways you can interact

with your surroundings, looking at objects in more detail, etc. My favourite

pastime is trying to ʽkissʼ everything in sight (for lack of a, er, stronger type

of approach) — you will get some pretty humorous lines in return. On the down

side, interaction with people is still limited to the ʽtalkʼ option which you can only

make use of once (which is really absurd at the end of the game, where you

surely earn the right to relax a little with your newly-found love); commands

like ʽaskʼ or ʽtellʼ are not supported. An unhappy element carried

over from the previous game is "event randomization" — on many an occasion,

your ability to perform some thing or other (mainly meeting other people) is

simply triggered on a random basis. In practical terms, this means that you

will almost inevitably get stuck at certain points, forgetting to wait for

prolonged periods of time on unpredictable screens or failing to return to

these screens several times in a row. I can understand how, from a certain

point of view, this would be beneficial to the player — extending the

gameplay and bringing a sense of profound satisfaction when accomplished —

but it certainly does little good for those who want to see some sort of

replay value in the game. |

|||||

|

Kingʼs Quest II is

certainly a "copy" of Kingʼs

Quest I, but hardly a "carbon" one. Almost every

aspect of the game has been enhanced, resulting in increased believability,

complexity, and replay value. With better graphics and sound, more subplots,

more humor, and a newly emerged sense of belonging to the "Sierra

continuum", it gives out a clear indication that its authors had no

intent of merely running on the proverbial spot. Therefore, if you are

playing Sierra games because you enjoy playing Sierra games, not because you

are writing a PhD on the history of the adventure game genre, this sequel is

inevitably superior. Yet at the same time, one cannot help but admit that the

game was rushed out fairly quickly, and it would take Kingʼs

Quest III to show that the fantasy adventure game still

had major unrealized potential in it. |

|||||