|

|

||||||

|

Studio: |

Sierra

On-Line |

|||||

|

Designer(s): |

Roberta

Williams |

|||||

|

Part of series: |

Kingʼs

Quest |

|||||

|

Release: |

October 1986 |

|||||

|

Main credits: |

Programming: Robert E. Heitman, Al Lowe, Bob Kernaghan |

|||||

|

Useful links: |

Playthrough: Part 1 (57 mins.) |

Part 2 (63 mins.) |

Part 3 (56 mins.) |

|||

|

By almost all accounts, King’s

Quest III gave quite a shock when it was released onto the unsuspecting

fans of King Graham, innocently grazing in the green CGA pastures of

Daventry. The opening «fanfares» were familiar, as was the logo, but their

ruler and benefactor did not walk onscreen to greet them. What appeared

instead was the grim, unsmiling, and — for that time — somewhat scary face of

a bearded magician sending lightning bolts from his fingers. Then came the

intro, and, again, no Graham, no Valanice, in fact, no kingdom of Daventry

whatsoever. You had the story of a slave boy named Gwydion, forced to live in

the service of the evil wizard with the lightning bolts, and there was no

evidence whatsoever that this slave boy had anything to do with anything in

the previous two games. Legend says that there was no limit to the fans’

indignation — not to mention that in those pre-neolithic days, there was no

Internet to help answer your questions and dissipate your doubts right on the

spot. As the game progressed, the

gamer would slowly begin to understand that, in some way, Gwydion’s fate would

be tied in with that of Daventry and King Graham, and about halfway through

it would become totally clear that this was not a «franchise reloading»,

but rather an intriguing and controversial move to perk up one’s interest.

But there was another catch: it took ages to GET «halfway through».

The game was much enhanced, for sure, but so was the difficulty. Even today’s

experienced gamers, if forced to play through King’s Quest III without

a hintbook, would have a hard time cracking some of the twisted puzzles, and

I am not even talking of the convoluted copy protection system, also a

first (and, alas, not the last) in the Sierra canon. And yet, all of the

frustration would eventually pay off. The aim of King’s Quest III was

to grip you tight, not relax you. The first two thirds of the game are among

the tensest experience one can get from Sierra On-Line: as Gwydion, you are involved

in a life-and-death struggle with your evil master, in which only a supreme

combination of intellect, speed, and agility can make you gain the upper

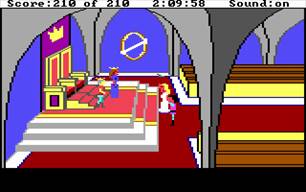

hand. The last third, where you can actually catch your breath, is

nevertheless also fraught with dangers at every step. But hard as it is, it

also gives an incomparable feeling of satisfaction once you overcome the

wizard, or when you finally make it to the end and restore peace and order in

your long-forgotten homeland. And however frustrated fans might have been,

this did not prevent them from making yet another sales hit of the game, or

from earning it rave reviews. To this day, it is one of the fans’ favorite

instalments in the series. |

||||||

|

Content evaluation |

||||||

|

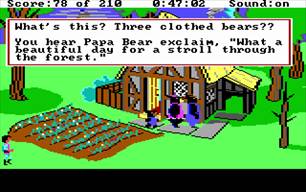

Many elements of the plot

are incorporated in strict accordance with the classic Roberta Williams

scheme: take a fairy tale / mythological motif that you have not used up yet

and stick it in when the player least expects it. There is really nothing to

equal the silliness of having just scaled the dangerous, precipitous cliffs

on which rests the evil home of your evil master, and find yourself straight

in front of... the house of the Three Bears, who have just decided to take an

innocent stroll in the forest. Why the Three Bears? God only knows. And only

a few screens to the left, you will find Medusa from the tale of Perseus. And

a few screens to the right, the Cave of the Oracle. How they all manage to

coexist in the same universe is something that only Roberta manages to

understand. But then again, do you really need

to understand it? Just suck it in, and suck it up. In other respects, though, To

Heir Is Human is a radical departure from the previous two instalments.

First, you are now given an explicit antagonist, an anti-hero with whom you

are locked in a concealed struggle for survival. This adds such dramatic

tension to the game as has never been experienced before — and works so well

that from now on, no King’s Quest would be without an explicit bad guy

(or gal). This particular bad guy, the evil wizard controlling your destiny,

is worked over very carefully; when he appears, he is not just running silly

all over the screen, like the bad guys in Daventry and Kolyma, but

materializes and vaporizes in puffs of smoke, and each of his appearances

makes sense — he is either there to silently watch over you, or to make an

announcement, or to order you around (and woe to you if the orders are not

carried out immediately). You REALLY get to hate him. REALLY. God, how I

hated him back in the day. Second, you have the

already mentioned intrigue of how all this ties in with the prequels. For

about half of the game, you have virtually no idea how it’s gonna end — well,

obviously, you know right from the start that you have to get rid of

the wizard, but it’s rather clear that this is more of a technical duty than

the true essence of your quest. The most important question is not, ‘how do I

get out of here?’, but ‘who AM I and what am I doing here?’ (And what have

the Three Bears got to do with it?). Third, the plot happens to

unravel in real time — with a clock mapping your progress and giving

you explicit (but approximate) indication of when is a good time to hide from

danger and when is a good time to head into it, the plot seriously gains in

realism. (It can get somewhat annoying when you replay the game, though —

second time around, you are most likely able to perform all the tasks

quickly, which leaves you twiddling your thumbs for a good while). Since the game is bigger,

it also makes the settings more diverse. All of King’s Quest I took

place in Daventry, and the «enchanted island» in King’s Quest II was

merely a footnote relative to all the stuff that happened in Kolyma. But here

you will be taking a long and exciting journey — being taken from your

original setting of Llewdor to a pirate ship, then to a high mountain range,

then to your native Daventry again (one that underwent some changes, though).

Another element of diversity is the ability to cast a variety of magic

spells, ingredients for which you have to gather all over the place. This

variety ensures that many obstacles in the game can be beaten in various

ways, a major improvement over the much more linear solutions in the previous

two games. |

||||||

|

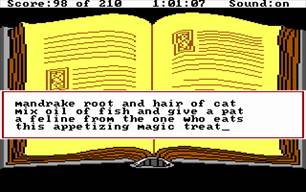

Not only are the puzzles in

King’s Quest III much harder than in the previous games, a few of them

are, in fact, some of the hardest puzzles ever to feature in a Sierra

game. Much of the difficulty has to do with a greatly improved and enhanced

parser (see below), giving you much more choice — and costing you a lot more

intellectual effort. But there is more to it than just tricky syntax. In the

previous games, action was pretty much limited to (a) LOOKING at everything

in sight, (b) TAKING everything that was not nailed down, (c) USING what you

have taken or GIVING what have you taken to people you encountered on your

way. Here, from time to time you have to perform more subtle actions. A large number of puzzles

revolve around your collecting ingredients for magic spells and then, later,

performing the actual spells. Preparation of the spells, however, is not an

actual puzzle; rather, it is an early and particularly twisted form of copy

protection, which has raised the ire of many a King’s Quest fan over

the years. Namely, in order to produce the desired effect, you not only have

to enter the number of the magical book page from the game’s manual, you also

have to copy — no typos, or you’re dead meat! — a large set of detailed

instructions, culminating in four lines of kiddie magic rhyme. Most people

howl about that, and for good reason — as if merely entering an unguessable

number from a page wasn’t enough. But, on the other hand, my guess is that

the authors of the game perceived a certain extra thrill in this mechanistic

re-typing of lengthy instructions and incantations, like the players were

really performing actual instructions found in an actual book of wizardry.

Besides, some of us here might need a spelling lesson from time to

time (wink wink). The most fun part, however, comes when you have your spells

all prepared and you can start experimenting with them (including on

yourself, which results in quite a few hilarious manners of death). Multiple

solutions are the norm here rather than the exception. The downside of the puzzles

is an overabundance of «arcade» sequences. Every single mountain path in

those regions seems to have intentionally been made about three inches wide,

and there seems to be a law against staircase railings or something. The road

to Daventry involves even more of these twisted paths and a tricky, annoying

climb on a rock surface (not nearly as dumb-planned as the beanstalk

ascension in King’s Quest I, but somewhere close to that range of

dumbness). Those who secretly cheered over the lack of this stuff in King’s

Quest II can go back to their air-punching routine. |

||||||

|

As I already mentioned

several times, the bulk of the atmosphere in the game is being created by the

hidden presence of Manannan the wizard. Even after replaying the game several

times, it is still possible to get the chills every time you start feeling

the guy is about to return from his journey and zap you to ashes for carrying

hidden ingredients. As long as he is active and a real threat, you never feel

safe wandering about Llewdor, but are always preoccupied about performing

your chores there as quickly as possible and getting back to the safety of

your little room. Once he is taken care of, oof! you get to revel in the

enjoyment of the beautiful countryside with renewed force, as well as a sense

of profound relaxation. Other than that, the

atmosphere is now becoming rather typical of King’s Quest: a nice

fantasy world where it is fun to escape to, but little that you haven’t seen

yet. Maybe one minor touch is the addition of an enormous desert world that

blocks your passage to the west — adding a certain sense of «inescapability»

(I suppose every single player must have tried at least once to get away from

Manannan «the easy way», only to die of heat and exhaustion a few screens

away) as well as vastness of the surrounding world. There is also a nice take

on the «scarred Daventry» world, with images that players used to remember

from the first game presented in a «devastated» perspective — the well

clogged with rocks, formerly beautiful meadows transformed into impassable

rifts and precipices, etc. This adds a decidedly odd nostalgic flavour. |

||||||

|

Technical features |

||||||

|

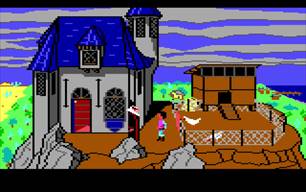

There are no radical

improvements here compared to King’s Quest II, but the game still

boasts an ever-increasing attention to detail. This is perhaps best evident

in the amount of «life» on screen: where the previous game was still mostly

static, Llewdor is almost Wall Street-level busy in comparison. Streams flow,

waterfalls pour, birds fly, squirrels chat with each other and wag their

tails, snakes and lizards crawl on the ground, and all of this looks as

natural as can be with a 16-color palette and three hundred pixels on the

screen. Movement is also enhanced by enlarging the number of intermediate

positions for most of the sprites. And the sprites themselves are pictured

more expressively — no longer are they viewable only as profiles without

shuddering. In particular, the sprite of Manannan, appearing and disappearing

in billows of smoke, with his beard, tall hat, and fiercely elongated eyes,

is one you shall soon learn to hate on a personal level. As for background images,

here, too, what used to be rendered in a fast, sketchy way, is now elaborated

on an entirely different level. Manannan’s dwelling is full to the brim with objects

of all kinds — pictures, maps, differently coloured books, wall decorations,

tapestries — giving the player ample time to explore all the possibilities

connected with this abundance (ample, that is, until Manannan gets back and

starts bossing you around). The pirate ship, with its variety of shields,

flags, construction details and such, is also quite a vivid place to explore.

Of all the early AGI games, King’s Quest III is easily the richest and

most colorful when it comes to graphics; only the upgrade to SCI and higher

resolutions would raise the standard even higher. |

||||||

|

There are some nifty

touches here in comparison to the previous games, but also some major

drawbacks. Problem number one is that by this time, Sierra people like

Margaret Lowe were already quite comfortable with milking the PC speaker for

all its worth and went on a creative spree, churning out as many musical

themes and special effects they could. But the PC speaker hadn’t changed much

over the previous three years, and its capabilities were simply abused. Many

of the sonic waves here are «aurally destructive» even today, when you

emulate the PC speaker on your progressive sound card and are in full control

of the volume; as for back in 1986, I bet most players just preferred to have

the sound turned off altogether. Sure, the grim «music» that

replaces ‘Greensleeves’ in the introduction to the game must have been an

unforgettable shock. A few of the happier themes are un-annoyingly cute and

giggly, like the one that accompanies the Three Bears wherever they are. And

the sounds that accompany Manannan’s appearance (gloomy fanfare-like note

sequence) and disappearance («whirly» sound, perfectly suitable for his

billows of smoke) are a brief touch of now-outdated genius. But other than

that, there are too many shrill, irky melodies relying on ugly frequencies

and notes that drag out long enough to choke you. The absolute nadir is in

Manannan’s laboratory, where you are forced to cast your spells to the sounds

of "mysterious music", which is not so much mysterious as

torturous: were the real-life Gwydion truly obliged to work his magic to that

kind of sound, he would probably end up with an atomic bomb in his pocket.

Fortunately, this was the last King’s Quest to be fully dependent on the

Speaker. |

||||||

|

Interface King’s Quest III’s major blessing and curse

at the same time is a radical improvement of the parser system. The game

understands a vast multitude of verbs and nouns now, and even prepositions —

in the previous games, most prepositions were either not recognized or

discarded, but here words like ‘under’ and ‘behind’ gain a special

importance, and this means that you won’t just get away with barely looking at

things whenever you are exploring a new location. Of course, this also makes

the gameplay much harder. The cruelest thing of all is that non-trivial

decisions can only be helpful in a very few cases, and chances are you will

encounter one of these special cases exactly by the time you have given up on

testing the limits of the parser and reverted to the old look – take – use

routine. Then you find yourself stuck and frustrated. Still, it certainly

boosts playing time. And so does the necessity to use the parser A LOT while

dealing with preparation and performing of your spells. Here, though, there

is no thinking to be done — just beware of typos. Moving around also reveals

a few interesting touches, such as the first ever «primitive physics» puzzle,

where you can carry and drop objects (one object, to be precise) at

will, although over a space of but two screens. Once you get hold of all the

magic spells, there is ample room to experiment with the transformational and

teleportational ones, which include some leeway and, strange as it seems, are

completely bug-free (not something Sierra could easily boast in its later

days). But in all other respects, there is little different about the

interface and gameplay. |

||||||

|

King’s Quest III pushed the AGI world

as far as it could ever evolve — with the possible exception of the parser

(also improved, but could have been even more sophisticated), all the other

aspects of the game milked the AGI engine for all it was worth. Graphics,

sound, scope, length, everything was first-rate for 1986. In terms of plot

intensity, it hasn’t aged one single bit since its inception; I can vividly

imagine new gamers drawn into the confrontation with Manannan as easily as

they did at the dawn of the computer age. Only a few steps short of

perfection — the story isn’t quite as nicely fleshed out as in some of the

sequels, and, come to think of it, the whole magic spellbook affair could

have been done in a less annoying way; but perfection is never achieved in

one step, and as good as the game is, Roberta would up the stakes once more

in the sequel. |

||||||