|

|

||||||

|

Studio: |

Sierra

On-Line |

|||||

|

Designer(s): |

Roberta

Williams |

|||||

|

Part of series: |

Kingʼs

Quest |

|||||

|

Release: |

September 1988 |

|||||

|

Main credits: |

Programming: Chane Fullmer, Ken Koch |

|||||

|

Useful links: |

Playthrough: Part 1 (60 mins.) |

Part 2 (61 mins.) |

Part 3 (69 mins.) |

|||

|

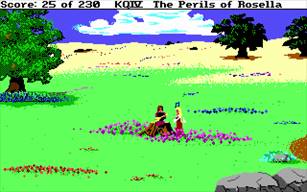

King’s Quest IV came into my own life relatively late — I distinctly remember

playing both Space Quest III and Leisure Suit Larry II much later than The Perils Of Rosella — meaning that I

never lived on my own through the life-changing experience it provided gamers

back in the fall of 1988. But I was still impressed when playing it for the

first time, and I still remain impressed even today, dusting it off for this

nostalgic review. Back then, it was every bit as revolutionary (perhaps even

more so) than the first King’s Quest game, but there is a difference: King’s Quest IV remains a beautiful

game even today. Its graphics look

respectably ancient rather than humiliatingly «dated»; its music sounds as

fresh and wonderful as ever; its perfectly constructed storyline still forms

a smoothly flowing fairy-tale narrative; and in its darkest moments, I dare

say it can still terrify a young player’s heart. Of course, the tremendous artistic

success of the game was largely due to the huge progress of the computing

industry in the mid-1980’s. Advances in processing and storing power,

transition to VGA, development of the first proper sound cards — Sierra was

one of the first game developers to make good use of all of that (somewhat to

the detriment of fans who could not afford this richness: I remember well how

much frickin’ time it would take to load a new screen or restore a game after

Rosella’s umpteenth demise, and I only heard the game’s music properly,

rather than through my trusty PC Speaker, some time in the mid-1990’s). But

the marvel of the game is that it is still a gas to play even in its

minimalistic, AGI-based early variant, with inferior graphics and no proper

music. The reason is that King’s Quest

IV also represented a major step forward in adventure game storytelling.

It featured a strong and resourceful female protagonist (yes, contrary to

religious rumors that strong playable female characters are still lacking in

video games, they actually go all the way back to Rosella in 1988); it took

place in real time, with a day-to-night cycle realised in stunning graphic

detail; it featured several interconnected subplots which you could take on

in any order; it improved upon the dialog and the text parser; it had a

wonderful mix of humor and terror; it made you actually care about the

characters — and rejoice in its happy ending (provided you’d actually

achieved it, because there was actually an alternate tragic ending). Along with The Colonel’s Bequest, the game represented Roberta Williams at

the height of her powers — her talents may have been insufficient to properly

establish her as a creator in the more modern age of computing (remember Phantasmagoria?), but she was just all

right for that crazy little period in 1988-89 when adventure gaming was just

entering adulthood. King’s Quest III

had already proven that she was capable of creating a truly gripping

experience, but the sequel went even further with its humanization of the

title character and deepening of suspense and intrigue. In retrospect, it

still remains a fairly naïve narrative, crudely concocted out of a bunch

of familiar fairy-tale motives, but the extra detalization, added

emotionality, and occasionally unexpected plot twists are all juicy enough to

overlook the simplicity of it all — something that is harder to do for King’s Quest III, and absolutely

impossible for the first two games in the series. Small wonder, then, that

the game became both a major critical and

commercial hit upon release — solidifying Sierra’s status and laying the

groundwork for what I still consider the truly golden period of the company

(1988-1990). |

||||||

|

Content evaluation |

||||||

|

Unlike the first two games,

King’s Quest III actually ended on

a cliffhanger — with King Graham flinging his adventurer’s hat in the air and

his two children rushing forward to pick it up, thus implying that there will be a sequel, come hell or high water.

So for those who had already played the previous game, King’s Quest IV confounded expectations right from the start.

First, as they saw King Graham collapse on the ground from a sudden heart

attack, they realized it was all going to get a lot more personal. Second, as

the storyline quickly congealed not around Prince Alexander, the protagonist

of the previous game, but around his sister, Princess Rosella, it would

quickly dawn upon them that they would have to step in the shoes (and, uh, in

the dress) of a girl princess — who would turn out to be anything but a damsel in distress, like she was

in King’s Quest III. Much has been written about Roberta

Williams’ fateful decision, but probably the best thing about it is that the

feminine nature of Rosella is not at all flaunted in the plot — in fact, most

of the time she is simply shown to be getting into the same kinds of perilous

situations, and braving them with the same wit and courage as her brother

Alexander. She may get a slight sexist remark or two from the rustic Seven

Dwarves, and there is a tiny bit of courting involved at the very end of the

game, but other than that, Rosella is just a sprite in a dress, albeit

rendered as more human-like through occasional close-ups and relatively

involved and emotional bits of dialog in the game’s intro and outro sections. In its essence, the plot is not that

much different from King’s Quest I

or II. In order to save her dying

father, King Graham, Rosella travels to the land of Tamir, where she has to

find a magic fruit (the smaller subplot of the game), as well as aid Genesta,

the local fairy, who had her magic talisman stolen by the evil witch Lolotte

and is now slowly dying without its power, as well as being unable to

teleport Rosella back home — this is the larger subplot, which involves

passing through several distinct trials and ultimately besting the witch.

What has significantly changed, though, is the level of detalization. There

are more locations, more characters, more puzzles, more interactions, more

suspense, and more sources of inspiration. This time, Roberta Williams pulls all the

stops and heavily borrows from all over the world. We have unicorns, Cupids,

Jonah whales, ogres guarding magic hens, traveling minstrels, zombies,

flesh-eating trees, the Graeae, the Seven Dwarves, and a mummy guarding

Pandora’s Box, all of them somehow managing to co-inhabit the couple dozen

screens of the land of Tamir and making it look much more vast than it

actually is. As usual, lots of questions remain unanswered — such as why, for

instance, is Pandora’s Box kept hidden in the crypt of a fearsome mummy which

shares the same property space with a dilapidated English manor? — but

somehow all these odd combinations still make more sense than having Little

Red Riding Hood merrily hippity-hopping a few yards away from Count Dracula’s

castle; the amount of detail that goes into all these settings reduces the

feeling that Roberta was simply pulling random shit out of her ass whenever

it was necessary to populate the next few square inches of Daventry or Kolyma

with something. Most importantly, though, the story of King’s Quest IV introduces a cohesive

and well-rounded plot. There really was no such thing to speak of in the

first two games, and the idea of King’s

Quest III was to let you know why you were playing this goddamn game in

the first place only when you were about two-thirds done with it. Here, you

are on a clear mission of rescue — save a dying father and a terminally ill

kind fairy — and you have a limited time cycle to carry it out, with each

next stage more demanding and complicated than the one before it. The

denouement, with one of the earlier plot twists cleverly reversed to make an

instrument of love into an instrument of revenge, is quite clever and

climactic, and upon completing the game, you will probably feel deep

satisfaction as Rosella lays down her Herculean burdens. |

||||||

|

The puzzle design in King’s Quest IV is relatively

benevolent compared to what may be encountered in an average Sierra game. As

long as you diligently explore your surroundings (which may be a daunting

task due not so much to the hugeness of the land, but to the increased level

of detalization), you will have your pockets bulging in no time, after which

it is usually just a matter of correctly choosing the right utensil at the

right opportunity. Unfortunately, the old stuck-o-rama curse does hit in a

few spots, as there are locations in the game which you cannot return to

after exploring (e.g. the little island in the middle of the sea), and if you

have failed to rummage through them properly, you will be forever stuck in

Tamir with no hope of fulfilling your mission. Wasting stuff is also severely

punished — do not even think of shooting that second arrow from Cupid’s bow

into the air, or you will be found sorely lacking in your hour of need;

likewise, your trusty spade only has a limited amount of charges before it

breaks into pieces, so use it sparingly. On the positive side,

despite the complexity of some of the puzzles, most of them seem logical — arguably

the strangest part of the quest takes part in a haunted mansion at night,

where you have to placate the roaming spirits for no obvious reason, but even

there it is rather the general setting that seems bizarre than the specific

tasks you have to perform, particularly if you take the time to read the

inscriptions on each of the cemetery’s tombs (and you should, some of them are quite hilarious). This is, in fact, one

of the few Sierra games which I remember being able to complete without

getting seriously stuck even once: chalk it up to intelligent and merciful puzzle

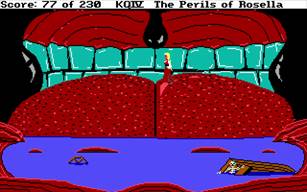

design throughout. As usual, the fun is occasionally

marred by platform-style challenges: King’s

Quest’s infamous ladders are back with a vengeance (particularly inside

Lolotte’s castle, where Rosella stands a much higher chance of breaking her

neck by falling down a few feet than she does being zapped by Lolotte

himself), and the long track down a dark cave with a carnivorous troll on

your back is quite a drag as well. Worst of the lot is the infamous whale

tongue sequence, where you have to carefully navigate the large, red, slippery

surface punctuated with dots which you think

probably somehow indicate the right path to navigate, but in reality they do

not — you can only proceed blindly, trying to memorize the path bit by bit

before you eventually get there. For some reason, apparently, Sierra

headquarters were not inundated by

death threats after they’d tried out a similar thing with King Graham

climbing up the beanstalk in the first game, so they were free to try and

pull that shit on us again here — goddammit. This time around, I guess, they

did get death threats after all, since the whale tongue became an internal

Sierra meme which would later be lambasto-referenced by Al Lowe in Leisure Suit Larry III, of all places.

Anyway, it’s not that bad — it

really only takes a few minutes to figure out the right path — but it is

always annoying to waste time, even small amounts of it, on blatantly stupid

challenges. |

||||||

|

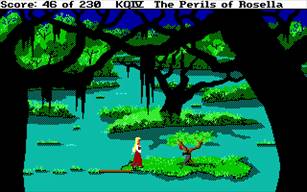

This is where the game

truly shines, in my opinion. In King’s

Quest III, the key component of atmosphere was tension and suspense — you

did not really have the inclination to stop and admire the scenery because

you knew that at any time, in any place you could have your ass kicked to

dust by the evil magician if you do not hurry up and gather those

ingredients. King’s Quest IV also

represents a battle against time, since once the day-night cycle is over, you

automatically fail in your mission; but this battle is more subtle and less

easily noticeable, actually giving you plenty of time to stop and look around

whenever you feel like it. And with the amount of loving detail that goes

into the scenery and the little animations, you were, of course, always

tempted to do just that. For all the diversity found

in the imaginary syncretized lands of Kolyma and Llewdor, the bare-bones

nature of their locations was always quick to remind you that puzzles come

first, beauty and feelings come second. The desert was there to make you

avoid poisonous snakes, the lawn in front of the Three Bears’ house was there

to help you get a thimbleful of dew — very pragmatic. Tamir, however, feels

like a land where you would actually be delighted (or, occasionally,

terrified) to take a walk, and it is not just

about the graphics. It is about the level of detail; it is about the

sometimes radical transitions between the atmosphere of adjacent screens; it

is about the subtle, but important modifications to the dialog system, both

between you and the narrator and between Rosella and the people she

encounters. It is about wishing to revisit all of Tamir’s areas at night,

just to see whether they look at all different from the daytime (they usually

do). A key element of the

earlier King’s Quest games,

starting from the second one, was to delineate «danger zones» and «safe

zones», so that you would be emotionally attracted to safe places like lawns

and seashores and reluctant to enter risky areas such as the poisonous lake

around Dracula’s castle. King’s Quest

IV’s Tamir pushes that principle to its limits (later games would

generally feature a set of different, more disjointed locations instead of

one huge chessboard), introducing a clever areal demarcation — most of the

danger zones are concentrated in the eastern part of the map, increasing as

you get closer to the mountain range that blocks passage to the right, while

the safest zones are all to the west, following a reasonably natural layout:

The Sea > The Meadows > The Forests > The Mountains. This means that

you will generally tend to stick to the sunny and green parts, with their

singing minstrels and dancing fawns and grazing unicorns, while only

reluctantly plunging into the shady and perilous eastern areas, controlled by

ogres, evil living trees, and, of course, Lolotte herself. This clever

arrangement, quickly setting up a fixed pattern of «West = Good, East = bad»

in your mind, makes King’s Quest IV

a far more immersive experience than its predecessors. Likewise, the suspense

during the game’s dangerous sections has also reached new heights here.

Enemies that pop out of nowhere are bigger, faster, and more intimidating

than the nuisances of the first three games — and if the huge ogre and his

equally huge wife at least prefer to roam the forest during the daytime, the

cave troll will be surprising you in the dark, because, well, he is a cave

troll after all; that part where you have to make your way to the other side

of the mountains is probably the creepiest moment in all of Sierra’s early

history. Which reminds me that Rosella is given absolutely no slack just because

she is a girl — death is as frequent a guest in King’s Quest IV as it was before, and although no gore is

involved, watching an evil ogre drag your protagonist away by her golden

braids was quite shocking by King’s

Quest standards (actually, looks seriously disturbing even today). Yet

even the scariest moments may be intertwined with humor if you so desire —

nothing truly beats the experience of reading aloud the hilarious

inscriptions on the cemetery’s tombstones right under the noses of

bloodthirsty scavenging zombies, for instance! |

||||||

|

Technical features |

||||||

|

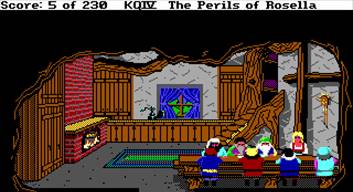

Ah, the graphics of King’s Quest IV. You know there is

something to be said about the visuals of a 1988 game when they still look

beautiful today — far more beautiful, in fact, than quite a few games from

the 1990s, especially the ugly early 3D experiments. Usually, this is chalked

up to Sierra’s transition from AGI to SCI (Sierra’s Creative Interpreter),

allowing for higher resolutions (320x200 pixels, no less!) and more colors

(16!) — but the truth is that the game looks seriously different from the

first three even in its early, barely available AGI version, meaning

that human artistic talent was just as much at work here as advances in

hardware. We might actually chalk

this up, at least partially, to the arrival of a new Sierra talent — William

D. Skirvin, who had replaced Doug MacNeill and Marc Crowe as the lead artist

for King’s Quest (he would also

work on most of the Leisure Suit Larry

games and some others as well). Under his directions, the world of King’s Quest made the most of

available colors and detail — you don’t really need to go further than the

comparison of the final shots of King’s

Quest III and the first shots of King’s

Quest IV, both picturing the exact same throne room of King Graham’s

castle in Daventry. The original still retains a bit of the austere spirit of

the original ASCII-based pseudographics, emphasizing shape over pattern; the

reworked image pretty much makes intelligent use of every single pixel,

dazzling the brain (okay, dazzling the 1988

brain) with a colorful patchwork where every piece of furniture, every wall

ornament, every item of clothing is pictured to reflect different grades of

lighting and shadow. Granted, the AGI version produces a highly smudged

effect due to the low resolution; but the VGA graphics rendered within SCI is

perfectly distinct and holds up fine today, as long as you do not try to play

the game in full screen mode on a modern screen. A whole lot of minor

creative touches was applied in the process. For the first time, we get a

proper distinction between outdoor and indoor perspective: outdoor landscapes

take up the whole screen and give you a smaller character sprite, while indoor

locations are slightly narrowed down and feature a larger and more detailed

Rosella, creating a more intimate — or, sometimes, more claustrophobic —

effect. We also get occasional close-ups of the characters, usually during

cutscenes in the intro and outro, also rendered in gorgeous detail (just look

at that fabulous screenshot of Rosella and Genesta with her multi-colored

fairy wings). Odd perspectives include looking out through a keyhole in the

ogre’s house, and, of course, the infamous inside of the whale’s mouth with a

strange perspective (Rosella has to climb all the way up to what seems to be

the whale’s teeth, yet is able at the same time to tickle his uvula — either

our girl has got very long arms or

somebody needs a lecture on cetacean anatomy). Finally, the most innovative

touch is the already mentioned day-and-night cycle: obviously, we are a very

long way from implementing that gradually on a real-time scale, but each

single outside location in Tamir is indeed presented in a daytime and a nighttime-colored

version, and the nighttime version manages to be reasonably intimidating

without sacrificing any daytime detail. Of course, it is probably a

futile affair to try and convince the average 21st century gamer about the

aesthetic wonders of a 1988 adventure video game, but you really only need to

compare it with a few other randomly chosen titles from the same era to

become aware of the visual superiority — King’s

Quest IV notably suffers less from pixel-itis in the modern era than many

of the later SCI-era games or, say, the pre-remake Secret Of Monkey Island, and, overall, of all the imaginary

locations in the franchise, Tamir ends up the one in which I’d most prefer to

spend my vacation, as long as it is possible to stick to the West Coast without

plunging too deep into the forests or mountains. |

||||||

|

For all of its

revolutionary qualities, arguably the

single most overwhelming thing about King’s

Quest IV was its soundtrack. The game was the first commercial PC release

to make use of the freshly developed sound cards (AdLib, Sound Blaster, etc.)

and MIDI synthesizer boards such as the Roland MT-32 — and in order to

emphasize this, Sierra spared no expense in hiring a professional composer,

William Goldstein. This results in not only the first proper musical soundtrack for a Sierra adventure game, but

also in one of the absolute best ones: Goldstein never worked with Sierra

again, and it wasn’t until Jane Jensen’s encounter with Robert Holmes that

the studio got itself a soundtrack composer of comparable stature. Since this is a soundtrack,

not a musical suite on its own, I will not go into major details, except

stating that the score is absolutely instrumental in supporting and enforcing

the atmosphere of magic, beauty, royal pomp, grievous solemnity, and

(occasionally) chilly dread of the game — and that Goldstein somehow manages

to do all that without falling victim to Disney-style sappy clichés

(up yours, King’s Quest VII!),

perhaps because he generally seems to look to folk and Renaissance-era music

stylistics for inspiration, or Bach on occasion (yes, there is a clichéd use of Bach’s

Toccata and Fugue in D Minor in one appropriate situation, but you don’t

really find me complaining about that). Needless to say, in order to be

properly associated, the soundtrack has

to be heard in its full glory with proper MT-32 emulation (the playthrough

links in the review provide precisely that experience), although I distinctly

remember the music being impressive even when played through a PC Speaker,

the first time I heard it: after all, a first-rate composer is always a

first-rate composer. In addition to the main

musical themes, the MIDI drivers provide tons of sound effects — roaring

ocean waves, whistling winds, chirping birds, croaking frogs, barking dogs,

neighing unicorns, everything you need to make the eco- and biodiversity of

Tamir come to life. (You do have to fiddle around quite a bit with the

emulation settings on modern PCs to have it all reproduced, though).

Curiously, this veritable overload of audio delights was not reproduced on

the same kind of scale in any other SCI-era Sierra game: it’s as if they

really blew all their load on King’s

Quest IV and then had to wait several years to rebuild their stamina

level. But while this is regrettable in general, in the case of King’s Quest IV it only makes the game

tower even higher over most of the competition — and make it an absolute

must-play even today for anybody who believes that the phrase «lasting value»

is at all appicable to a video game. |

||||||

|

Interface One aspect in which King’s Quest IV still stubbornly clung

to its past (and I, for one, welcome that type of conservatism) was in

preserving the old text parser system. They could have changed that — Maniac

Mansion had already shown the world how this could be done, and King’s Quest IV does feature full-on

mouse support, meaning that you can move Rosella around and select menu

options without resorting to cursor or functional keys on the keyboard. But

apparently, Ken and Roberta were not yet fully convinced that the

point-and-click future was the right kind of future for adventure games, and

decided to stick with the parser after all. One major technical change

from the earlier AGI interpreter is that the parser now works differently:

where prior to 1988 you were typing stuff into the command line below the

graphic screen «in real time», meaning that you could walk around and type at

the same time, with SCI the command line is no longer a ubiquitous part of

the screen but, instead, appears each time you begin to type something in,

pausing the game in the process. This has two small, but nice advantages —

first, you get to enjoy a larger screen, and second, you are no longer in

danger of having your ass kicked by some roaming enemy while desperately paying

attention to the orthography of «pour toadstool powder into thermonuclear

reactor» (well, not exactly, but...). The trade-off is that, by not being

able to walk and type at the same time, you slow your game down a bit, but

this was really only a problem in the early days on weak PCs, when even

setting game speed to fastest still made the character crawl across the

screen like a snail on amphetamines. As for the power of the

parser itself, this is where things have neither significantly improved nor

worsened since King’s Quest III. I

do not remember any serious fuck-ups when trying to come up with a working

verbalization for any of the necessary actions (unlike, say, some of the

really silly jams in SCI-era Leisure

Suit Larry games), but neither were there any particularly interesting

extra options, other than a reply of "Not in front of the other game

players!" to ‘undress’ or "Perhaps you need to purchase a copy of Leisure Suit Larry?" to any

randomly used expletive. In other words, the parser, just like the overhead

menu, was quite strictly functional: nothing to detract from the

straightahead game experience. Which is hardly a bad thing when the

experience is on such a superior level. |

||||||

|

Although no game is perfect, and most

certainly no Sierra On-Line game was ever perfect, it is almost impossible to

imagine a better adventure game than King’s Quest IV to have been

produced in 1988. In time, technology and imagination would naturally make

obsolete both the game’s technical advances and simplistic/formulaic

storyline. But just as we are still capable of being amazed, for instance, at

the level of mastery and imagination involved in the making of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper, easily giving in to its

magic despite the outdated nature of its technological and musical

philosophy, I think that King’s Quest IV is one of those games that

easily stands the test of time as a fully playable experience, not

just a curious museum piece. If ever you need a fully involving, immersive

experience of a good old-fashioned fairy tale, with perfectly defined black

and white tiles (all-good heroes against all-evil villains and all that), simple

enough while still coming up with a solid challenge, pristine yet beautiful

in its visuals, and featuring one of the most immersive early video game

soundtracks ever, Princess Rosella is still available as your potential alter

ego. |

||||||