|

|

||||||

|

Studio: |

Sierra

On-Line |

|||||

|

Designer(s): |

Roberta

Williams |

|||||

|

Part of series: |

Kingʼs

Quest |

|||||

|

Release: |

November 9, 1990 |

|||||

|

Main credits: |

Lead Programmer: Chris Iden |

|||||

|

Useful links: |

Playthrough: Part 1 (62 mins.) |

Part 2 (65 mins.) |

Part 3 (68 mins.) |

|||

|

Few games were more

revolutionary in the history of Sierra On-Line than King’s Quest V — perhaps King’s

Quest I... maybe King’s Quest IV...

could be King’s Quest III... well,

you get the drift: whatever huge changes the world at large commandeered from

Sierra, in those years you could always count on Roberta Williams to step

forward as their flagwoman. (Well, then again, she was the boss’ wife, after all.) That said, «revolutionary» does

not necessarily mean «best», be it politics, music, or video games, and there

is hardly a better example of «revolutionary done wrong» than this game,

which has always elicited very mixed reactions from me. As the Nineties brought

along further advances in processing power, graphic resolutions, and digital

sound technologies, Sierra did its best to adapt: with increasing competition

from younger, bolder players on the scene (LucasArts, in particular, had

firmly established itself as a strong force to be reckoned with), Ken

Williams was clearly determined to remain on the cutting edge. King’s Quest V was the first in what

could be called the «third generation» of Sierra games, clearly distinguished

from the previous one by three important changes: (a) new and improved VGA

graphics, with background images now typically painted and scanned in; (b)

new and improved sound technologies, finally allowing for full-on voice

acting to replace (or complement) text boxes; and, most importantly, (c)

complete removal of the text parser in favor of a new point-and-click

interface. The latter decision was clearly influenced by the competition

(e.g. such LucasArts games as Loom,

which had completely dropped the verbal aspects of earlier games like Maniac Mansion and introduced the

quintessential point-and-click experience) — and, in my humble opinion, was

the single most devastating choice in the history of plot-based video games,

but more on that below. Along with all these massive changes

came a good story — King Graham was brought back from the near-dead for such

a monumental occasion, and sent in pursuit of the evil wizard Mordack who had

just kidnapped his entire family and

his castle, for no apparent reason. The narrative and dialog, still mainly

controlled by Roberta Williams, were rather old-fashioned for 1990, but

tolerable. The changes to the graphic system and the interface, fresh and

dazzling, were also received warmly — but when two years later, in 1992, the

floppy disc edition was followed by the fully voiced CD-ROM version, critical

reaction was a bit more reserved, largely due to the lack of professional

actors involved (all the voicing was done by Sierra staff). As time went by

and what was once novel became the norm, the attitude towards King’s Quest V cooled down significantly,

to the extent that today it is generally remembered as one of the weakest

games in the series, or, at the very least, a serious misstep caught in

between two masterpieces (IV and VI). How much of that negativity

reflects historical justice, and how much constitutes revisionist injustice?

Read on to find out. |

||||||

|

Content evaluation |

||||||

|

King’s Quest V was the last game in the series for which Roberta Williams was

credited as sole designer — meaning that she actually wrote all the plot and

dialog, unlike later games, where she acted more like a mentor while the

actual job was done by other writers (Jane Jensen, Lorelei Shannon). This

signifies another old-fashioned, traditionally-stylized experience, a story

of noble rescue and a plotline peppered with randomly written characters from

all over the world of European folklore... and, in theory at least, there is

nothing wrong with that. One significant feature of

the game’s plot is that it is very

tightly tied to the previous games — King’s

Quest IV may have set the ball rolling with its plot directly continuing

from the mild cliffhanger at the end of III,

but other than a few moments in the intro, the game still functioned

perfectly well as a stand-alone title. King’s

Quest V, marking the triumphant return of King Graham as the active

protagonist, seems seriously preoccupied with its own mythology, and could

not be easily recommended to players who had not already subscribed to the

Roberta Williams fanclub years ago. At the very beginning of the game, we see

a mysterious figure appearing out of thin air and apparently «pocketing»

Graham’s castle along with everyone who lives in it (the everyone in

question, surprisingly, only including Graham’s wife, son, and daughter — the

servants must have all gotten bonus tickets to Disneyland). Eventually, with

the aid of his friends, King Graham is able to get to the bottom of this and

crack the identity of the cloaked kidnapper, but that identity will still be

a bit of a puzzle to anyone who had not played King’s Quest III, and the effect will not be quite the same. The initial setting is, in fact, very

similar to that of King’s Quest IV.

Tragedy strikes (Graham suffers a heart attack — Graham’s family is

kidnapped), an unexpected magical assistant materializes out of nowhere

(Fairy Genesta — Cedric the Owl) and lures the protagonist out to a distant

land (Tamir — Serenia) by some or other means of insta-travel (teleportation

— magic dust). What expects you next is a lot of wandering through the brave

new world, sorting out various people’s problems and getting important gifts,

until you finally encounter the archvillain (Lolotte — Mordack) and use their

own strengths against them (no spoilers, sorry!). In other words, Roberta did

not exactly jump sky high to bring us a fresh new plot — but she did come up

with a few fresh twists on old storylines, which is more than enough for a King’s Quest game. Or maybe not quite enough, particularly for old fans of the series: too many

elements seem rather lazily rehashed from past games — evil snake blocking

your path from King’s Quest II,

endless deadly desert from King’s Quest

III, abominable snowman from King’s

Quest III again, and many other encounters which just substitute old

characters with new while leaving the old tropes intact. If ever, for some

reason, you decide to binge your way through all the series, multiple waves

of déjà vu are practically guaranteed. The only principal

difference is the introduction of a sidekick — Cedric the Owl, who

accompanies you throughout the game for absolutely no reason other than whine

and annoy you to no end (and it gets even worse if you play the voiced

version, see below for more on that). Some of Roberta’s synthetic elements

feel rather poorly integrated into the atmosphere of the game — namely, the

desert sequence which, for some reason, features elements from Arabian Nights; this is at least

something new, but seeing the oh-so-British King Graham suddenly transform

into Aladdin for a few moments is, to put it mildly, rather inconsistent with

the overall tone of King’s Quest,

though probably not catastrophic. On the positive side, the game’s

conclusion, with an epic magic battle of wits between the hero and the

villain, adds tension and drama — for the first time in the series, the final

challenge is not a single action which you can leisurely type in on your

keyboard, but an actual multi-move timed test of intelligence which actually feels like a challenge. Later King’s Quest games would try to follow

the same tension-building climactic rush in their finale, but this is one

aspect on which King’s Quest V has

them all beat. Unfortunately, just one. |

||||||

|

As Sierra’s first proper

point-and-click game, King’s Quest V

is not terribly imaginative. You can Look at stuff, Use / Take stuff, and

Talk to people — which essentially means that most solutions to most puzzles

involve taking detachable object X and using it on undetachable object /

person Y, as they would in fact do in most point-and-click games from then

on. The actual actions needing to be performed are fairly simple and logical;

the main difficulty lies in scoping out the rather vast (for 1990) land of

Serenia, since you typically need to go to one end of the world in order to

pick up an object there that you need to exchange for another object in the

opposite end of the world, only to return with it to the former end of the

world etc. etc. — prepare yourself for quite a bit of backtracking, and never

forget to save. In fact, never forget to

save in multiple slots, because King’s Quest V suffers from a

particularly bad case of dead-end-itis. Leave Serenia for your journey across

the mountains without even a single necessary object, and you’re a goner.

Accidentally waste a necessary object, and you’ll never see paradise. And, in

perhaps the game’s most maligned episode, blink once to miss a crucial event

(just a cat chasing a mouse), and half an hour later you are dead without

even properly understanding what it is you did wrong in the first place.

Today, gamers will mercilessly label this as piss-poor game design; back in

1990, they would be more likely to just accept these things as tough

challenges and keep a stiff upper lip. Who cares if there is no way to know

that you absolutely need that

custard pie for your mountain crossing? The important thing is that you can get that custard pie before you

cross that mountain, and whatever you can

get, you should get. Such is the

logic of classic adventure games — and what exactly makes it less logical

than any absurd actions you must take in your favorite arcade games, or the

endlessly unrealistic deeds you do in your RPGs? Anyway, while a small

handful of puzzles here does border on the utterly absurd (particularly the

one that involves getting rid of the yeti), the majority are straightforward,

and your biggest difficulties will be getting stuck in unwinnable situations

because you tried to complete the challenges in the wrong order. (Hint: do

the desert challenge before trying to

whoop the evil forest witch’s ass, or frustration will follow you to the end

of your days). My biggest

difficulties, the way I remember them, were getting through all the darn

mazes — first, trying to figure out all the right beelines between water

sources in the desert, and second, trying to find my way in the geometrically

confusing dungeons underneath Mordack’s castle, which almost look like an

early predecessor to the disorienting jumbles of corridors in early Elder Scrolls games (not exactly Daggerfall level of confusion, but as

close as you could expect of an adventure game from 1990). Still, while much of the

retro criticism of the game prefers to focus on bad memories of the yeti

puzzle or of Graham dying in prison because he failed to befriend his

potential savior, I prefer to fondly remember the end of the game and that

climactic battle of wits with Mordack — that

was a fun and innovative bit of design, and it yielded a very satisfactory

ending to the game. |

||||||

|

For some reason, Serenia,

the place where you are likely to spend about 2/3 of your playing time, fails

to fully recapture the charm and horror of King’s Quest IV’s Tamir — even despite the obvious technical

superiority of the graphics. Perhaps it is due to the land actually being

quite small: one screen for an

entire town, about 10 more for all the adjoining outskirts and forests, and a

huge, endless, largely procedurally generated desert which literally dwarfs

the country. Like Tamir and everything else, Serenia is also divided into

relatively «safe» and «dangerous» zones (this time, with a literal warning

sign that marks the danger zone), but the lack of transitional areas is

rather befuddling — the layout of Tamir was more convincing, with the land

gradually getting darker and darker from west to east. Here, it’s more like,

Grandpa Dwarf takes three steps out of his cuddly home and runs into danger

of being froggified by the evil witch. All in all, the game seems

to have been designed rather pragmatically: it is much easier to get lost in

Mordack’s boring dungeon maze than in the land of Serenia, where each screen

is tightly and functionally loaded (and the game itself, by the way, is

fairly short — a complete playthrough runs for about 3 hours), so there is

fairly little joy in wandering around it from end to end. The diversity in

atmosphere between the safe and danger zones is nice, and the danger zone

itself (the evil forest) is beautifully designed, with horrific-looking

plants and red eyes blinking at you from random spots on the screen, but

everything is just too small to leave a lasting impression... and that

includes the mountain crossing and

Queen Icebella’s palace and the

little beach spot and the island

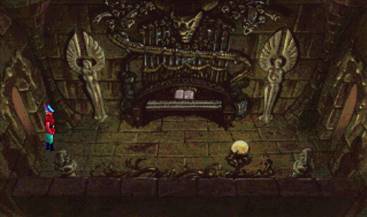

with the harpies, anyway, you get the drift. Arguably the single most

atmospheric space in the game is Mordack’s castle — the beautifully eerie

Gothic designs, the gloomy ambient music, and the constant feeling of danger

just behind your back combine to make that last part of the game into one of

the scariest segments in any King’s

Quest game, period: earlier games lacked the graphical and sonic assets

to achieve that effect, and later games, even such a masterpiece as King’s Quest VI, would feel more

cuddly and family-friendly even in their darkest moments. Taken together with

the already mentioned epic battle at the end, this turns the last half-hour

of the game into an experience that can unsettle and impress the player even

today. Too bad you have to slog through everything else in order to get

around to it — but for those with patience, it’s well worth it. |

||||||

|

Technical features |

||||||

|

King’s Quest V marked the arrival of a new graphic era for Sierra: with

256-color VGA, and the ability to actually paint the backdrops by hand and

then scan them in digitally, the game differed from its predecessors like

night and day. To celebrate these technical achievements, Sierra hired an

actual graphic artist and illustrator with previous experience in TV

animation, Andy Hoyos, and he made sure that the backdrops and cut scenes,

for the first time ever, began to look like actual pictures rather than pixel-based

digital art. Naturally, the resolutions (320x200 native) were still way below

anything properly acceptable for a well-detailed picture, but if you do not

concentrate on making out facial features of the characters and instead

concentrate on the broad brush strokes, there is plenty to like, and some of

the backdrops are even impressively impressionistic. There are occasional

touches of vivid imagination in the artwork — for instance, in the shapes of

wild plants in the evil forest, sometimes looking like giant mutated

agglomerations of bear traps; in the mish-mashed quasi-abstract bunches of

crystals within the Crystal Cave; certainly in the designs of Mordack’s

castle interiors, where traditional Gothic shapes mingle with an odd

fascination for claw, tooth, and bone (the entire game, I might add, feels

rather «toothy» and «bony»). That said, an artist’s wild idiosyncratic

rampage King’s Quest V is not: this is still the domain of

Roberta Williams, and Roberta Williams is fairly conservative when it comes

to such established genres as fairy tales, fantasy, or horror. So do not

expect anything particularly out of the ordinary — Loom or Grim Fandango

this is not. In terms of sprites and

animations, the game apparently introduced special techniques based on

rotoscoping live actors, borrowing the mechanics from Disney — though it

probably takes a very trained eye

in the modern world to detect that, given the crippling limitations of

then-current graphic resolution. Still, there is no denying that all character

sprites are now both much more detailed and

feature a much larger and a much smoother set of motion poses, looking less

and less like matchboxes on legs and more and more like figures of real

people when seen through the eyes of somebody with real low visual acuity. A

nice touch is that, while talking, most of the characters receive special

enhanced close-ups, with well-animated facial movements; these were further

enhanced in the «talkie» version of the game and smoothly synchronized with

the audio (again, a truly big achievement for the early 1990s). The only

regrettable thing is that there should have been many more cut-scene

presentations — the most realistic and pretty shots of the game are the ones

where the camera zooms in on the characters, which, unfortunately, happens

only several times during the play. |

||||||

|

The original version of the

game came on floppy discs and predictably contained no talking — only a

musical soundtrack and some SFX effects. The soundtrack, credited to Sierra’s

veteran Mark Seibert and newcomer Ken Allen, is decent, but nothing

particularly special, a clear step down from the complexity and energy levels

of King’s Quest IV: much of it is

just built on fairly generic functional motives (generic gypsy music for the

gypsy scene, generic Eastern dance music for the Eastern scenes, generic

gloom-and-doom soundscape for the Mordack Castle scenes, etc.). The sound

effect work, however, is quite commendable: for most of the game, you are

accompanied with lively noises (chirping birds in pretty forests, scary birds

in evil forests, people hustling and bustling in busy towns, cold winds

blowing in the mountains, waves crashing on the seashore, wicked brews

bubbling in Mordack’s laboratory, etc.): such a dazzling variety was never to

be found in even the most show-off-ey of Sierra’s second-generation games. Yet most importantly, of

course, in 1992 King’s Quest V came

out on CD-ROM and became Sierra’s first fully voiced title — though this is

precisely where the idea of «revolutionary does not always equal good» comes

out in full. With voice acting in video games still being a very fresh thing,

Sierra’s management was either unable or not willing to call for professional

voice actors, meaning that all the voicing had to be done by the staff

members themselves: thus, artist Andy Hoyos tries his best to voice the evil

wizard Mordack, composer Mark Seibert voices the briefly appearing Genie, and

Roberta Williams herself voices... the pip-squeaky Rat. New addition Josh

Mandel, who would soon be playing a significant role in Sierra’s design and

writing history, does a decent enough job with King Graham (rather wooden,

but then Graham himself has always been a fairly wooden character). However, the biggest

slip-up was committed with the character of Cedric the Owl, voiced by

programmer Richard Aronson — for some reason, everybody thought it was a good

idea to make him deliver all the lines in a shrill «hooting» falsetto, and

this, coupled with Cedric’s annoying and totally unnecessary presence in the

first place, quickly turned poor Cedric into arguably the single most hated

Sierra character of all time; if you are a veteran, too, you most certainly

remember the immortal line "Graham, watch

out! A POISONOUS snake!" like it were only yesterday. Then

again, sometimes gruesomely inept easily translates into hilariously

unforgettable, and at least Sierra’s masterminds were sufficiently aware of

this to allow poor Cedric to be properly grilled and lambasted, as an inside

joke, in multiple future games (from Al Lowe’s Freddy Pharkas, where you can find the poor guy being picked

apart by vultures, to Space Quest IV,

where you can shoot him down as a bonus prize in the Astro Chicken arcade). Ironically, my own biggest

personal gripe with the soundtrack is that, this being Sierra’s first voiced

title and all, there is still no way to get the voice acting and the text boxes to appear at the

same time — which may be annoying even for native English speakers, since the

sound quality of the acting is relatively lo-fi, noisy, and hard to

understand whenever somebody sets a natural filter on their voice, be it

Roberta’s pip-squeak or Aronson’s helium falsetto. Later games would correct

that mistake and always let you listen and read at the same time (apart from

the FMV titles in the catalog), but here it’s either pick the floppy disc

version with the text, or the CD version with speech (which are also slightly

different in terms of available lines of dialogs and descriptions, though not

by much), and, apparently, the fan community was not able or not willing to

try and splice both with some fan-made patch (not that I blame them —

submitting yourself to hours upon hours of testing the compatibility limits

of Cedric’s dialog is quite an exotic torture). Still, an achievement is an

achievement, and it does not always have to be carried out in perfect style.

For a little cherry on top, King’s

Quest V even features the first ever fully instrumentated and voiced bit

of singing, in the form of a little

melancholy folk ballad performed by the Weeping Willow (played by Debbie

Seibert, surprisingly a much better singer than her husband Mark is an actor

— then again, if I am not mistaken, she does have a BA in vocal performance).

It is short and nothing special either melodically or lyrically, but at least

I would definitely take it over Sierra’s later attempts at power balladry

such as ‘Girl In The Tower’. |

||||||

|

Interface And here we are — Sierra’s

most drastic change ever, a death sentence for the text parser and transition

to the point-and-click interface: as I have always insisted and will continue

to insist until my dying day, the single worst decision in adventure game

history, and worthy at least of the Top 5 worst decisions in gaming history,

period. An opinion with which few gamers will agree — in 1990, the change was

welcomed by fans and critics alike, and endless retro reviews of the games

always keep pointing out how wonderful it was for the simple and economic

point-and-click interface to replace the clumsy and nearly always broken text

parser which had caused so much frustration. Yet instead of going the

difficult, but promising and intriguing route — fixing the parser, so that, in time, it would become more and

more intelligent and give the player more and more creative freedom over

one’s choices — Sierra went the easy way and eliminated those choices

altogether, limiting the player to the oh-so-wonderful option of searching

out hotspots on the screen and poking them with the mouse cursor, which went

in a whoppin’ FOUR different shapes: Walk, Look, Take/Use, and Talk. Amazing! I distinctly remember those

days of the first point-and-click Sierra games, and certainly remember how

disgusted I was and how this pretty much turned me off from adventure gaming

for quite a long time — the only things that saved the experience for me were

the continued and ever-improving degrees of storytelling and atmospheric

immersion. It does not help, either, that King

Quest V’s interface is so defiantly simplistic: at least some of the

better future titles from Sierra tried to introduce slightly more variety in

the amount of performable actions (like the «smell» and «taste» icons of Space Quest IV, or the tasteless, but

strangely comforting «zipper» icon in Larry

games, or a full set of physical actions in thee first Gabriel Knight), but here all you can do is helplessly grab at

things, and so many things aren’t even grabbable! Not to mention the lack of

true hotspots — miss an important object by a millimeter and you will get the

impression that it might not be important at all, when in fact it is. Apparently, re-orienting

the SCI engine towards a point-and-click interface first time around was such

a demanding affair that the result is extremely sparse — absolutely nothing

other than the above-mentioned icons in the menu, plus the usual

save-restore-restart-quit options. The only addition to the gameplay is the

laconic «combat system» at the end, where you get a menu box and may select a

particular shape to which you want to shift: it’s fun, but hardly worth

remembering as an outstanding feature. All in all, it has always been, and

continues to remain for me, as prime evidence for the inferiority of the

point-and-click system to a well-trained parser: I always have more fun

replaying King’s Quest IV than this

game precisely for that reason. |

||||||

|

It might be an exaggeration to state that

the slow and shameful death of Sierra On-Line began with King’s Quest V

— particularly given the abundance of stellar titles that the studio released

in the 1990s — but in retrospect, the game does feel like an inauspicious

first sign of the company’s imminent demise. Up until that game, pretty much

all of Sierra’s truly innovative titles (and most of those were King’s

Quest games, too!) innovated for a good reason, and those innovations

were usually a joy to behold and experience. The innovations of King’s

Quest V, however, mostly ranged from dubious and controversial to

embarrassing and poorly implemented. The revised graphics were technically

stunning, but did not look nearly enough as a true labor of love like those

in King’s Quest IV. The addition of speech was a fine achievement, but

the voicing itself left a hell of a lot to be desired. And the removal of the

text parser in favor of a point-and-click interface was, at best, a deeply

divisive move — a perfect favor for the fans, in the eyes of some, and a

suck-it-up move towards the dumbification of the adventure game experience,

in the eyes of others (myself included). In short, it was all a massive

revision of objectively or seemingly outdated standards that was done with

nowhere near the same brilliance and efficiency as it was in the past — and

it was at least partially due to Sierra beginning to function more and more

like a business organization and less and less as a company of idealistic

nerds who were more out there for fun and excitement than to make money, even

if they still made money a-plenty. Just the first small signs, mind you,

nothing much to worry about — Sierra would still go on to have at least half

a decade worth of artistic success — but if you ever wanted to write a Rise

And Fall Of The Sierra Empire, you’d probably have to use 1990 as the

entry point for the Fall chapters. In the meantime, want it or not, you still have

to play King’s Quest V if you do not want to be left without the important

missing link between IV and VI. You might want to select the

old floppy disc version, though — that way, you won’t have to put up with

Cedric the Owl too much (though you will have to put up with the extra

hassle of Sierra’s annoying copy protection), and you are certainly not

missing anything if you do not get acquainted with the lovely tones of other

Sierra employees, either. |

||||||