|

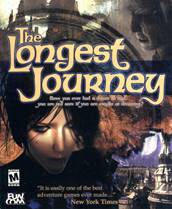

The Longest Journey |

|

|||

|

Studio: |

Funcom |

|||

|

Designer(s): |

Ragnar

Tørnquist |

|||

|

Part of series: |

The

Longest Journey |

|||

|

Release: |

November 18, 1999 |

|||

|

Main credits: |

Programming: Morten Lode, Audun

Tørnquist Art: Didrik Tollefsen Music: Bjørn Arve Lagim |

|||

|

Useful links: |

Complete

playthrough, parts 1-17 (17 hours

20 mins.) |

|||

|

Conventional historical

narrative (such as ensconced in Wikipedia, among other sources) tells us

that, although adventure games were essentially dead in the US by the turn of

the millennium, they continued to persevere on the European market — which

was originally quite slow to catch up with the express trains of Sierra

On-Line, LucasArts, and Cyan, but turned out gallant enough to pick up the

fallen banner once American gamers had decided that expeditely shooting stuff

up was, after all, much preferable to slowly solving stupid puzzles. While this is not completely true (no generalization

ever is), a brief look at a representative list of

adventure games does indeed confirm that sometime around the late 1990s /

early 2000s the balance switches in favor of such European studios as Cryo

Interactive (France), Microids (also France), House of Tales (Germany),

Detalion (Poland), Future Games (Czech), and others; most of these were

relatively small-scale studios with limited budgets and, consequently, small

backlogs (Sierra’s list of titles dwarfs each and every one of them), but in

between them all, they at least somehow managed to keep adventure game design

on the list of paid jobs (as opposed to completely falling into the hands of

computer-savvy devotees working D.I.Y. style on their off days, of which

there was also a lot in the early 21st century). The problem, unfortunately,

was that in order to prove the ongoing vitality of the genre, you did not

just need a studio willing to pay for the job — you needed people with vision, the European equivalents of

legends like Roberta Williams and Al Lowe and Ron Gilbert and Tim Schaefer

and Jane Jensen or, heck, at least the Miller brothers; people who would not

merely pay tribute to the big successes of the previous decades, but actually

advance them in a variety of ways. The main reason why

relatively few of the games produced by these studios achieved great fame on

the international market was not the international market’s willing ignorance

of adventure game titles as such, but precisely the fact that, while many of

them were nice and all, they did not exactly demolish the stereotype of an

adventure game as something that belongs squarely in the past. Even a

genuinely visionary game like Benoît Sokal’s Syberia could still be critically lambasted on so many points

that defending it on some sort of «objective» level would be nigh impossible.

To keep the genre alive, the European market needed to produce at least one game that would unquestionably,

irrefutably make all or most of the Top 10 Adventure Game lists of all time

for years to come. That game happened to be Ragnar Tørnquist’s The Longest Journey — and it totally

and absolutely deserved it. Tørnquist, a

handsomely dashing (if I do say so myself) Norwegian graduate of Oxford’s St

Clare’s School, was hardly what one would call a technician — in his college

days, he mostly studied philosophy, history, and art, and eventually got

sufficiently savvy in drawing and animation to be hired at Norway’s studio

Funcom as a writer and designer. From 1993 to 1999, Funcom was mainly known

for small-scale action and sports games, some of them licensed from Disney

and other film studios — nothing particularly special or critically

acclaimed. However, once its new designer gradually rose high enough in the

ranks, he pitched a creative idea which would probably have been vetoed by

any American videogame studio at the time. Funcom, whose managers might not

yet have learned to calculate their budgets that properly, had the good sense to support it — and ended up

with such a critical and commercial winner on their hands that it allowed

them... to go into the MMORPG market and produce titles like Age Of Conan and The Secret World. Okay then. What exactly was the

secret of The Longest Journey? It

was certainly not a game immune to criticism, as we shall see below in extra

detail — from the more than questionable graphics to the often ridiculously

difficult not-that-crap-again puzzles, one could (and did) accuse it of the

exact same sins which, in many people’s eyes, had doomed the original

adventure game market. Its universe and storyline, though certainly original

and even unique in some ways (we shall get to this soon), would hardly be

enough to make people forgive the game’s transgressions. I read many a

thumbs-down review of The Longest

Journey from people who just «didn’t get it» — mostly because they

focused their attention too much on infamous travesties such as the Rubber Duck

Puzzle (see below), and stopped right before making that small, but necessary

leap of imagination which would have brought them to the exact place where

they needed to be. But change the angle just a bit — make a quick duck

sideways to avoid staring into the large hat of the lady in the seat in front

of you — and all will be different. It is not coincidental

that one of the chief inspirations for The

Longest Journey, in Ragnar’s own words, was Gabriel Knight: Sins Of The Fathers — and, unlike me, he wasn’t

even a fan of Sierra games in general. That

game, however, struck him as being unusually deep, realistic, and

well-researched compared to everything else at the time, and he was

determined to take all these qualities even further. His game would completely dispense with the idea of a Narrator,

transplanting you once and for all inside the conscience of his protagonist —

a protagonist who would walk, talk, and react as close to a real human being

as possible, even when (especially

when) placed in shocking, supernatural circumstances. His universe would be a multi-layered one, with a back history

and lore rivaled by RPGs rather than old school adventure games with their

annoying plot holes and tons of questions that needed answering but weren’t

going to be answered. His way of

thinking would be to combine the best aspects of Sierra — intriguing story,

epic flair, emotional pull — with the best aspects of LucasArts — humor,

satire, and comfortable game design. An important additional

factor is that, while Ragnar might certainly be described as one of the

earliest game designers with a well-defined «SJW attitude» — something that

became more and more prominent in the Longest

Journey franchise as time went by — he is also one of the few who knows

how to handle it just right, or, at least, knew back in 1999. With its female

protagonist who was simply impossible not to take a liking to (well, unless

you were on the Rush Limbaugh level or something), The Longest Journey probably did more for the cause of equity than

any other game before it — Tørnquist proudly reported (though I have

no idea how he got the data) that about 50% of people who played the game

were women, which would typically be reported as an expected and predictable

result for something like The Sims,

but hardly for a point-and-click adventure game. Something tells me, however,

that he would never have achieved this result if the game were merely a

blunt, rigid, clichéd piece of feminist propaganda — instead, its

moral values are promoted subtly and, in general, take second place to plot,

puzzles, and overall atmosphere. His April Ryan does share a lot of features

in common with Jane Jensen’s Gabriel Knight — as she does with many other

modern fairy-tale heroes, in fact — but in some ways, of course, she is the

perfect antithesis of her inspiration, making it rather hilarious to think

about how one of the most endearing «sexist» male characters in videogaming

was written by a woman, while one of the most inspiring «anti-sexist» female

characters in the same genre was written by a man. Whether The Longest Journey did indeed

single-handedly save the adventure game genre from floundering, or whether it

was at least tremendously influential on all adventure games to come, are

difficult and subjective questions which I am not equipped to answer (for one

thing, I simply do not know enough of adventure game history in the 21st

century). But at that particular moment, at least, with the game received so

enthusiastically at the exact same time that Sierra and LucasArts were both

going down in flames, it really might have seemed to be a critical

passing-the-baton moment — with a new generation of intellectual European

designers continuing to push forward where American boomers had run out of

steam. And even if truth is always more boring than myth, I’m certainly ready

as heck to keep pushing the myth if it ensures that some people at least will

continue enjoying the hell out of this flawed, but wonderful game. |

||||

|

Content evaluation |

||||

|

If there is exactly one thing about The Longest Journey that can have me

immediately take it down a peg, it is that, for all of his inventiveness,

Tørnquist decided to pin it upon one of the most tired tropes in

existence — «A Nobody Becomes The Chosen One And Saves The World» (oh why, oh

why does it always have to be The

World? couldn’t, just for once, it have been the local kebab stand instead?).

It is an admirable achievement of his that, having picked that one (and I do

believe that video games abuse the shit out of it on an even more casual

basis than literature or cinema), he was able to run as far with it as he

did. Still, it did cost me a few hours of relative disappointment once the story

of April Ryan began to unfurl, and hence a warning: yes, it is a great game

with a solid plot, but do be prepared that you will have to be the chosen one

and save the world. (And for the record, Gabriel Knight did not have to save

the world, he only had to prevent St. Louis Cathedral from collapsing). In Ragnar’s defense, the world that he

did create was, to the best of my knowledge, rather unprecedented in the

gaming world; at the very least, in no previous game would that kind of world

be laid out in so much detail and with so much care. As the 18-year old

aspiring artist April Ryan, you live in the year 2209 AD on one side of The

Divide — in our own world, which bears the code name of Stark and is

apparently ruled by Logic and Science; meanwhile, the other side of The Divide, bearing the name of Arcadia (why not

Shangri-La?), is the domain of Magic and Chaos, and is populated by all sorts

of wond’rous races and creatures (no elves or dwarves, at least). Apparently,

both worlds were once one, but then Maggie dropped the salt or something, and

in order to save the universe from collapsing in on itself and creating heavy

metals, Science and Magic were separated from each other, and a special

Guardian of the Balance between the two was appointed to keep watch on both

sides from an interdimensional hub. Unfortunately, the latest Guardian turned

out a little paranoid, and one day abandoned his post without warning —

upsetting the Balance and setting up a chain of events that could join the

two worlds back together and unleash Chaos upon both, much to the delight of

a group of conspirators on both sides («the Vanguard») who had been dreaming

of getting things exactly that way for a long time now... This entire story is told in much,

much, much detail some time into

the game and, frankly, constitutes its weakest part. There is nothing all

that unusual, per se, in the concept of an alternate unseen universe right

before our noses, to which certain endowed personalities can «shift» at will

(cue Hogwarts and all). What is

unusual is that Tørnquist places his starting world two hundred years

into the future and has you more or less equally divide up your time between

Hogwarts and Surrey, that is, Stark and Arcadia. Thus, The Longest Journey is equal parts cyberpunk and fantasy, defying genre conventions and setting up an

interesting precedent — in particular, it allows Ragnar to try out his

socio-political models on a conjectured future and a quasi-medieval

fairy-tale space at the same time, showing how the same logic is applicable

everywhere (in a nutshell: people get angry and pissed off everywhere, and crave for new leaders

and new ideas, no matter how risky and dangerous, to help them alleviate

their poverty, their boredom, or both). This already makes for an interesting

setting, which makes it easier to forgive the entire line of the «Guardian of

the Balance» and the magic disc that you have to reassemble from four or more

different pieces. What is even more interesting is that the actual plot of

the game is far from predictable. Ragnar is an odd guy with whom you can

never tell — one moment he seems to be enslaving himself to fairy-tale

clichés, then the next minute he gets busy inverting and

deconstructing them. April’s trips between Stark and Arcadia, for one thing,

are completely unpredictable — he Shifts her to another dimension when you

least expect her to be Shifted, and he can send you off on a monumentally

long side quest errand just as you are expecting to get busy with the main

quest. Emotional (sometimes corny-emotional) scenes lodge side by side with

sarcastic and humorous ones. Secondary characters who seem to be there to

help you only end up baffling you, and vice versa. All of this confusion can certainly

irritate a player expecting something more straightforward; check out, for

instance, this curious

essay on how one found the experience «frustratingly childlike» in its

approach. «Childlike» I could maybe agree with, but «frustratingly»? As far

as I am concerned, the humor, sarcasm, and occasional breaking of the fourth

wall in the game is an essential part of its charm, without which it would

play out like one of those JRPGs that take themselves way too seriously and

ultimately reward you with a duncecap for suspending your disbelief. If anything, I actually find the game

lacking precisely in those moments when the script goes for too much pathos

and forgets to dampen it with enough humor — a case in point is when April

first gets to Arcadia, and the local priest gives her a lengthy digest of the

entire History of the Balance while using the temple frescoes as illustrative

material and the sweeping orchestral soundtrack for emotional support. This

sequence is long, confusing, way

too serious and hinting that, maybe, the writer has finally bitten off more

than he, or we, can chew at this particular moment — especially because we

never really saw it coming, since all the previous sequences in Stark, long

or short, were well-tempered with doubts, jokes, and witticisms. Fortunately,

The Longest Journey does not have a

lot of such sequences over its duration (and it is quite a long journey: my complete playthrough that includes

most of the dialogue runs well over 17 hours, which is most certainly a

record time for an adventure game title as of 1999). Of course, ultimately everything

depends on how you receive the character of April Ryan. Her shtick — which

clearly shows a huge Gabriel Knight influence — is in liking to mix

seriousness with sarcasm, empathy with humor, and even (sometimes depending

on your dialogue choices) humility and submissiveness with self-confidence

and arrogance. In other words, she is quite a multi-dimensional human being, and

that is what I’d like to be, too, if I ever got caught up in those kinds of

situations: deflating fear, shock, and bewilderment with humor. It is true

that she does not get to experience a lot of character growth throughout the

game, more or less exuding the same mix of sympathetic idealism and humorous

cynicism from the first to the seventeenth hour of the playthrough, but since

the entire game takes place over several days, it’s not as if she’d be

equipped with too much time for this anyway. (And, for the record, she does

undergo a complete transformation of her character by the time of the sequel

game, Dreamfall — but we shall

leave that for its own story). Empathy and sarcasm alone would not

suffice, of course, if they were not properly worded; and the quality of the

writing in the game is usually exceptional (for games, that is). The very

first sentences uttered by April, as she finds herself stranded on some rocky

height in the middle of a recurring nightmare: "Oh no, don’t tell me I’m dreaming, again. You know, for once — just

for once! — it would be nice to have a decent night’s sleep without waking up

screaming from a bad dream at four AM". Then, looking at the

approaching dark cloud: "Even the

weather sucks in my dreams. I feel so charmed". Yes, that’s Gabriel

Knight all over for you (who also begins the game with a recurring nightmare),

but with a tad more internalized focus on yours pretty, as would befit an

enthusiastic teenage soul in the late 1990s (not to mention the late 2200s). And

she bites, too: after the initial shock of having a conversation with a

talking tree is replaced with annoyance at the latter’s condescending remarks

("oh, we do not expect a human to

come to our aid"), she snaps back with "lose the attitude, okay?" Thus we have most of the

discerning features of the character established in about five minutes. Complaints about the game often focus

on the length of the dialogue: indeed, in his eagerness to bring depth and

realism to the screen, Ragnar often goes overboard — for instance, the full

conversation with April’s flamboyantly lesbian landlord Fiona, with all the

dialogue branches explored, takes up about 15 minutes of voice acting —that’s

just one conversation, and quite a

lot of it, such as the juicy details of Fiona’s intimate life, is entirely

irrelevant to the story; in fact, Fiona herself is but a minor character, who

has exactly two scenes in the early part of the game and then reappears only

briefly toward the end. But while I could probably agree with the criticism

that too many agents are introduced in the early parts of the game whose

story arcs are never brought to conclusion (Fiona, her girlfriend, April’s

friends Emma and Charlie, etc. etc.), I could not agree that those parts of

Tørnquist’s dialogue that are not essential to the story are entirely

useless altogether — more than a story-teller, Ragnar is a world-builder, and

with two separate planes of existence, the man has got quite a bit of world

to build. Almost every character in the game who

has more than two or three lines of text is a distinct personality — even a

couple of lazy repairmen whom April has to convince to put together a broken

door at the police station (one is lazy, rude, and sexist; the other is lazy

and mentally retarded). At least three in particular deserve to be placed in

a Hall of Fame for outstanding merits, all of them encountered in Arcadia.

One is Abnaxus of the Venar, a flegmatic, frog-like creature whose people

manage to exist outside of the dimension of time, which makes it hard for him

to communicate in any language that demands obligatory grammatical marking of

tense ("It was late, April Ryan.

You were tired. We have talked in the morning when you come to visit me"

— I’d advise the poor fella to switch to Mandarin, actually). Most likely, he

is simply written in because Ragnar wanted to write in somebody particularly

unusual, Castañeda-style, but since we are not obligated to revere the

guy as a guru or anything, we can just enjoy his perspective in the overall

context. The other one is evil alchemist Roper

Klacks, who lives in a stone tower in the middle of a swamp and has to be

tackled by April because he imprisoned the wind needed to take her ship where

she needs to go. He is quite self-consciously evil in a Monty Python, or

maybe even in an Austin Powers, kind of way — as well as a fan of

automobiles, telephones, and America’s Funniest Home Videos. This kind of

villain is rather inherited from LucasArts than Sierra, and would easily fit

into the context of a Day Of The

Tentacle — particularly when April has the choice of challenging him to a

set of contests, including hopscotch, tic-tac-toe, spelling bees, and

Shakespeare recitals, all of which lead to hilarious losses for her. (Silly

fussy people who post walkthroughs on YouTube always miss those activities

and go straight for the calculator challenge — guys, the game is not called

The Longest Journey for nothing!). Another legend in his own right is

Crow, April’s sidekick who, like most sidekicks, is added for comic relief

(as if there wasn’t enough comedy without him already!). Lazy, lascivious,

politically incorrect, he comes from a long line of Sancho Panzas, and

although, other than his being a crow and all, I can hardly think of anything

that makes him particularly unusual in that line, he just does a good job of

deflating April’s ego from time to time, as well as faithfully playing out

the Taoist image of the Least Significant Being in the Universe Making All

the Difference. That said, the efficiency of his character probably has more

to do with his voice actor than his spoken lines, so we’ll get to that in its

proper time. Special mention should be made of the

game’s finale, which I won’t spoil for those who have not played the game;

let’s just say that Ragnar is not much of a fan of happy endings (neither am

I), and I can think of few other games in which the act of saving the world

left behind such a sharply pronounced feeling of dissatisfaction. I mean,

people would go on to curse the ending of Mass

Effect in large part due to the unavailability of the «and they lived

happily ever after» option, but at least BioWare made sure that the galaxy

was saved in a truly Monumental Fashion; you could be indignant about your

own insignificance, but you could not deny the atmospheric importance of the

moment on a grand scale. In The Longest

Journey, the saving of the world is done so casually that you hardly even

notice. You might as well just have saved that kebab stand. But the trick is

that you will be feeling empty and dissatisfied along with your title

character — empathy on the prowl — and that will most certainly get you

thinking about whether saving the world is really worth it, as well as the

balance between individual importance and freedom of will, on one hand, and

destiny / karma, on the other, that sort of thing. Morale of the story: if

you absolutely do have to have yet another round of gratuitous world-saving,

at least make sure that you got absolutely nothing out of it. Maybe next time

you’ll think twice before listening to creepy old men and overrating the

importance of your nightmares. |

||||

|

In later years, when Ragnar would

design the sequels to The Longest

Journey (Dreamfall and Dreamfall Chapters), he would be

consciously drifting away from the 1990s adventure game model, focusing

almost entirely on the story and downgrading the actual challenges to an

almost elementary level. The original game, however, was still very much

aware of its point-and-click adventure nature — and although I get the

feeling that Ragnar himself was getting caught up so much in the story that

the difficulty of the puzzles curvaceously dropped all through the game, the

first several chapters present quite substantial obstacles on your way to

restoring the Balance. Nothing particularly unusual about them — most of what

you have to do is related to finding stuff and manipulating it one way or the

other — but the same kind of criticism that is commonly applied to classic

Sierra and LucasArts games is just as easily applicable to The Longest Journey as well. At least one of the puzzles — the

infamous Rubber Duck Challenge — has probably been featured on every worst-of

list of challenges in adventure game history (which is good, because The Longest Journey still needs all

the publicity it can get). At one point early in the game, you need to get an

electrified key off the subway rails in order to use it in a completely

different location, and to do that, you need a bit of rubber and some

leverage. Any normal person, of course, could have simply bought a pair of

rubber gloves, but since the city of Newport seems to be strangely devoid of

general stores, you shall have to do with whatever is lying around, and

concoct a pretty grotesque device to achieve your goal. That said, you could at least

theoretically imagine your rubber duck device existing and functioning in the

real world — you’d probably have to go through several months of training to

learn to use it properly, but it could

exist. To me, far more logic-defying is yet another frustrating puzzle from

the same chapter, when you have to get a rather dim-witted movie theater employee

out of your way by tricking him with a toy monkey (called «Constable

Guybrush», by the way) and some additional paraphernalia — I remember having

far more trouble with that puzzle

just because I could never bring myself to believe that the answer would be

on that level of phantasmagoric.

What makes the whole thing even more unpleasant is that the preceding parts

of the game roll along smoothly and do not in any way prepare you for this

level of difficulty or absurdity — and that both the Rubber Duck puzzle and

the Constable Guybrush puzzle are only necessary because you have to sneak

inside a movie theater... when you could instead have simply bought an entry

ticket or something. Fortunately, once you have your first

Shift and finally get to Arcadia, such situations are trimmed down to a

minimum, and the game becomes much more balanced and logical on the whole,

while still retaining a reasonable level of difficulty. Every once in a

while, Ragnar introduces a «special» puzzle — such as finding your way in the

cheating maze of Roper Klacks’ castle, or building a magical telephone line

on the island of Alais — but these are original and fun to do. Sometimes

success depends on whether you have done enough reading (in the Marcurian

library) or talking (do have patience and try to exhaust most of the dialogue

trees with your talkative NPCs — it is often impossible to progress without

doing so), but this is more a matter of diligent perseverance than anything

else. In strict accordance with the classic

LucasArts codex, Ragnar makes sure that the game can never place you in an

unwinnable state — even despite lots and lots of traveling from place to

place, April can never technically end up anywhere where she is not in

possession of or cannot pick up an object required to complete her next

objective — and that you can never die, not even in the direst situations.

The latter is actually weirdly unrealistic: for instance, in one case you end

up locked inside a small tree house with the local Baba Yaga on the prowl,

and both of you will simply end up standing opposite each other, with the

game waiting indefinitely until you complete the required action to win.

Similarly, you cannot drown, get burned, be captured, be devoured by the

Chaos Storm — all of which is convenient for the player, but detrimental from

an atmospheric perspective, since it essentially transforms both Stark and

Arcadia into completely safe zones, while story-wise, the game is constantly

trying to tell you exactly the opposite. This is one aspect of the game that

Ragnar probably realized was wrong himself, since he would fully reinstate

the possibility of dying for Dreamfall. Finally, the LucasArts strategy is also

adhered to in dialogue trees, where the player often has a choice of replying

in several different ways — yet the choices almost never matter, apart from

just one decision, taken early in the game, which will lead you to go through

one out of two possible supernatural experiences. Most of the time, the

different options are only there for you to build a slightly more appropriate

personality for April; you can react more rudely or more politely, with more

sympathy or more sarcasm, more inquisitiveness or more indifference, etc.,

the final outcome will, as a rule, always be the same. (There is a curious

moment when one of the characters, the disgustingly foul-mouthed but helpful

Flipper, promises you to reveal more of his backstory if you truthfully

answer his question of "are you a virgin?" — and although both

"I am a virgin" and "None of your business" are both

options, apparently the required answer is "I’m not a virgin", as

it is the only one that will get the guy to disclose himself to you.

Apparently, Ragnar believes that for an 18-year old to remain a virgin in

2209 is beyond believability — in which case one could, of course, wonder why

the hell would the Flipper even bother to come up with the question). But at

least it makes for a tiny bit of replay value. In any case, a few specific complaints

aside, there is no question that The

Longest Journey is indeed a game, not just an interactive movie

experience — and a pretty solid one as far as adventure game rules / logic

are concerned. This might turn into a problem if you are enraptured with the

story (and I wouldn’t blame you), but, fortunately, the most difficult

puzzles will be there for you before

you get the chance to become fully enraptured, so, all in all, Ragnar

Tørnquist may be fully deserving of his own title — Guardian of the

Balance. |

||||

|

As I already mentioned, the most unique

feature of The Longest Journey is

that it combines two distinct genres — cyberpunk and fantasy — in hopes of

making you yourself feel all possible parallels and distinctions between the

two. Both of Ragnar’s imaginary

worlds, Stark and Arcadia, are clearly influenced by (and, in parts, copied

from) various sci-fi and fantasy works, yet both also strive to be original

enough for us to at least respect, if not necessarily admire, the attempt. At

the very least, the universe of The

Longest Journey cannot be called «generic»: it is a focused artistic

creation, rather than merely a convention for testing out playing strategies

and solving puzzles. Of the two worlds, be it here or in the

Dreamfall sequels, I must say that

I always prefer Stark. Arcadia, the land of Magic and Chaos, is imaginative

enough, but much too often, it just seems that the author’s main concern here

was about how to make this place not

seem like any other magic place ever created. Hence, no generic elves or

dwarves — in their place, we get the blue-skinned exotic Dolmari

(fortunately, this was ten years before Avatar),

the genetically-related but evolution-separated aquatic Maerum and aerial

Alatiens, and the faceless Dark People, who look like a more talkative and

bibliophilic variant of the Dementors. But despite all of Ragnar’s noble

efforts, Arcadia still does not end up looking that much different from the average fantasy / fairy-tale world

out there (honestly, there’s just so many of them that conjuring up a fully

original one even in 1999 would be akin to trying to write a completely

original three-chord punk rock tune). An evil wizard turning people to stone,

an ugly old hag luring innocent travelers to her house for dinner, a sea

monster speared by a brave hero... now where exactly have we seen all this

before? It is perhaps most obvious when you get

to the Alatien village where you have to listen to four lengthy folk tales in

order to get the correct answers for an audience with the Elder — all of them

are variations on traditional motives (such as the myth of Icarus), albeit

with a noticeable feminist flair (such as the Icarus in question being a

girl, which does not save her from sharing the same fate). They certainly

aren’t irritating variations or anything; it’s just that it is hard for me to

fall in love with Ragnar’s Arcadia as a whole.

Specific characters can be wonderful, such as Abnaxus or the gentle giant

Q’aman with his Zen attitude ("Man,

you got relaxing down to a fine art!" – "Q’aman not be knowing anything about fine art. He be a philistine"),

but the world as a whole is nowhere near as impressive as, say, Tim

Schaefer’s Land of the Dead from Grim

Fandango, which came out only one year earlier. Tørnquist’s «Stark», however —

essentially our own world two hundred years into the future — is a completely

different matter. It is an extremely interesting half-utopian paradise,

half-dystopian nightmare, which also has lots of literary and cinematographic

parallels (comparisons to Blade Runner

are fairly frequent), but does not quite ideally fit in any of the models I

am familiar with. The game begins in «Venice», a charmingly dirty bohemian

area of the bigger city of Newport (April: "Rust is the very definition of Venetian architecture. Venice wouldn’t

be the same without the rust. It would be better, but not the same")

populated by free-thinking spirits and peppered with cool bars and art

schools — yet the first object in April’s reality with which she can have a

conversation is a «friendly» voice communication terminal who, upon learning

that she does not have sufficient funds, warns her to "refrain from voice communication in the

future, or you will be reported to the F.U.B. and charged for processing time"

(April: "F.U.B.?".

Terminal: "Fair Use Bureau. They

are authorized to carry deadly arms"). This three-way contrast between

intoxicating creative freedom, impressive technological progress, and

vigilant police state defines everything in Newport (and, it may be assumed,

Stark in general). Apparently, the world is run by a tight alliance between

corporate interest and security forces, to the extent that, as a

semi-friendly cop consents to explain to April, "the police department is a subdivision of the Bokamba/Mercer Company

and the Bingo! Corporation" (April: "Doesn’t that constitute a conflict of interest?" Cop: "Not if we don’t arrest any employees of

either company"). Class segregation is rampant (April will even have

to get a special ID to take her where she needs to go in the end), drug

addiction in crime-ridden quarters is worse than in the city of Baltimore,

yet in all the spheres that are not necessarily tied to corporate activity,

there is total freedom — freedom of creativity, freedom of worship, etc. And

technological warfare, in which government and corporate agencies battle

brave little hackers protecting individual freedoms, runs deep and wide. This angle, as you can probably already

see from bits of dialogue, allows Ragnar to drag in a lot of sarcastic humor,

most of which actually works — maybe even too much humor, since in his next

games he would continue to depict Stark in a more serious light, leaving most

of the humor to specific select characters. Interacting with this weird world

as April, poking fun at its inconsistencies, bureaucratic stupor, and

undercooked artificial intelligence, is a gas — there is, for instance, an

extremely easy-to-miss sequence where April tries to get inside the police

station through the front door (most people just go for the covert entrance

right away) and is stopped by a cop who is an actually an actor practicing

for his next role, but was still hired for the job to save the powers-that-be

a bit of expenses (Cop: "I’m not a

weirdo! I’m an actor!" April: "No offense, but... isn’t that an oxymoron?"). A sequence

that is impossible to miss is one

where poor April has to go through the hellish procedure of getting just the

right official form to get the couple of repairmen off their lunch break

(Police lady: "The 09042-A? Why

the hell didn’t you ask me for that one in the first place?" April:

"Because I’m a cruel bitch, and I

love torturing you. In fact, I’ve made it my life’s mission to haunt you

forever and ever with requests for useless forms and documents.")

And just wait until April finally makes it to Colonial Services, where people

are essentially taken away to nearby asteroids for a lifetime of indentured

servitude ("how does it feel to

work for the Dark Side?") As dark-humorous and parodic as it all

seems, Ragnar’s Stark might, in fact, be one of the most believable

portrayals of our not-too-far-removed future (next to all the zombie

apocalypses, of course) that I have seen in the world of videogames, so it is

hardly surprising that I have really enjoyed spending quite a bit of time

with April in Stark, and could not help but be a little sad every time she

got whisked away to another adventure in Arcadia. To make things even more

snappy, Ragnar sometimes inserts his ideas on how history — even recent, 20th

century, history — shall eventually become compressed and flattened out in

the minds of people of the future: thus, one of the game’s main characters,

the mysterious old Cortez, is introduced as a fan of «old movies», so April

has to seek him out at a vintage movie theater, where she can read the titles

to some of the movies and share her ideas with us ("‘The Maltese Falcon’... oh yeah, I remember this one. It’s a Disney

cartoon about a falcon who, uh, goes looking for a black cauldron... it’s got

singing mice in it, I think... I mean, don’t they all?"). Or, when

she gets her hands on an old pocket calculator that somehow made its way to

Arcadia, she mentions something about "Elizabethan times", and it would be rash to think that she

actually meant Elizabeth II. Precisely because the game is so fun

and sharp whenever it is taking a satirical turn, I am less pleased when it

tries to take itself more seriously. In particular, all that mumbo-jumbo

about the Balance, the Guardian, the Draic Kin, the Vanguard, the magic disc,

etc., essentially most of the «core lore» of the game, could take a hike for

all I care — for all I know, it is only there to give you an excuse to travel

from place to place, meet colorful characters, and be proud of yourself for

earning achievement after achievement (by the end of the game, April will be

able to introduce herself as «The Wave», «The Windbringer», «The

Waterstiller», «The Venar Kan-ang-la», and «Bandu-embata of the Banda»,

earning more titles than an Achaemenid King of Kings). The game is always at

its best not when it tries to be pathetic and monumental, but cozy and homely

— Ragnar is just so much better at writing the first half of Fellowship of the Ring than Return of the King, if you get my

drift. Still, all is forgiven with the game’s

final act, which could have

included a lot of drama and cheesy epicness, but instead prefers to offer a

surprisingly chamber-like conclusion; at one point, it unexpectedly jumps

into psychologically disturbing territory (the vision of April’s Dad — not a particularly pleasant spectacle

for those who are easily shocked and offended), and then, as I have already

mentioned, leaves our poor protagonist at a crossroads with absolutely no

idea of what to do next — with the dialogue, the music, the visuals

beautifully (if the word ‘beautiful’ is applicable here at all) conveying

this feeling of emptiness which you get when you get your job done to no

gratification whatsoever. It acts, at the same time, as a hook — you know you

desperately need to get back to

this world, because this cannot be and will not be the end, not by any

physical means — and as a harsh reminder about "what does man gain by all

the toil at which he toils under the sun?" It is easily the least

satisfying and the single best

ending to an adventure game up to that point — well worth enduring all the

puffed-up lore for. In conclusion, it should be added that

most of the atmospheric qualities of the game are provided by the writing —

and the voice acting: as we shall see below, The Longest Journey is quite flawed (even for its time) when it

comes to the visual aspect, which, unfortunately, will be an immediate

turn-off for many players, particularly those who like to complain about the

length of the dialogue or the «immaturity» of the title character (because,

apparently, having a sharp sense of humour and irony is seen by some people

as «immaturity»). But if you are willing to look past the technical flaws and

concentrate primarily on the substantial virtues, the universe of The Longest Journey will be genuinely

hard to forget. |

||||

|

Technical features |

||||

|

And this is where we come

to the tragic part. Oh, if only The

Longest Journey had been designed three or four years later, when 3D

graphics had reached a certain acceptable condition... or three or four years

earlier, when 3D was not yet really

a thing and they might have considered embracing a 2D cartoon style instead.

But it was released in 1999, when everybody was supposed to go 3D — at a time when properly handling the art of

turning polygons into human beings was the prerogative of the few lucky

wizards, such as Valve, for instance. And who could expect a technological

miracle from a small, peripheral studio in Norway, of all places? This is not to say that

Funcom lacked artistic talent. Creative and even visionary digital artists

can arise anywhere, and Didrik Tollefsen, who was in charge of the art

department of the project, made sure that at least the painted backdrops

would reflect Ragnar’s fantasy as loyally as possible. Be it the rusty,

post-industrial wastescapes of Venice, or the classically influenced

architectural interiors of Marcuria, or the wild, overgrown jungle of Alais Island,

the basic art for The Longest Journey

is... well, maybe not stunning, at

least not superficially (I’d say the overall color palette is a bit too

brown-grayish for that), but certainly sufficient to maintain a constant feel

of immersion. The amount of detail, in particular, is first-rate for a

more-than-20 year old game: it really makes one mad that you cannot open most

of those doors and windows or even get detailed verbal descriptions of the

depicted objects — all the clocks, contraptions, grotesqueries, weird plants,

mysterious statues, etc. There are only but a few screens depicting the

underwater kingdom of the Maerum, but nobody had managed to depict underwater

environment in such a kaleidoscopic fashion prior to this game. The work on shades and

colors has to be commended as well — for instance, when April finally embarks

on her sea journey, you begin with a picture of the captain’s deck at dusk,

capturing a gorgeous sunset with highly realistic rolling waves; once the

ship is hit by the storm, the same picture changes to a darker-blueish tint, with

the waves reflecting the dark-blue tint of the sky, as well as being animated

in a far more aggressive pattern (and remember how goshdarn hard it was to

make realistic 3D depictions of water in the late 1990s? not even Half-Life did that properly). Yet for all the great work

done on the backdrop renders and on bringing them to animated life, the team

somehow managed to absolutely fall flat on their faces when it came to

generating and animating character sprites. My latest playthrough of the game

involved greatly beautifying it by installing the excellent Longest Journey HD mod, whose creator(s)

succeeded in thoroughly depixelating the original graphics without ruining

the game’s feel. However, not even a full-scale HD mod can do anything with

the fact that the 3D characters in the game look and move like crude

cardboard cutouts, with ridiculously deformed, smoothed-out body parts and

facial features that, at best, look painted-on and, at worst, are

non-existent. This is truly discomforting because sometimes the images are at

odds with the narrative — for instance, Cortez, April’s first and most

important guide into the world of the supernatural, is commonly referred to

as an old, unattractive guy, but you could never even begin to tell his age

(in fact, you might not even be able to tell his sex) while watching his lanky sprite stretched out on a bench or

huddled in the back of the movie theater. Worst of all, I am not

entirely convinced that all of the blame should be laid squarely on

technology. Gabriel Knight 3, for

instance, which came out in the same year and was dependent even more heavily

on 3D (it actually had a rotating camera instead of pre-rendered backdrops),

did a far better job in making at least the characters’ faces (if not necessarily their limbs or their hair) somewhat

more realistic and more emotional. It was not entirely a matter of low

resolution, either: perhaps the most deplorable graphic moments in the game

are the (thankfully, few) cutscenes in which the usually small-scale sprites

are enlarged and you actually get to see the faces of the characters in

close-up — you’d think they could rise up to the challenge at least on this

occasion, but... well, here is the first really large close-up of April’s

face you get to see in the game:

Now it is definitely

commendable that Ragnar always tries to avoid sexualizing his lead female

characters (although it does not quite agree with the observation that he really likes showing them off in their

underwear, or that April’s butt seems to be, uh, fairly disproportionate to

the rest of her body), but come on, there are quite a few options in between Rita Hayworth and Mary Ann Bevan —

and given that April would eventually earn a far more handsome look in the

games that followed, I can hardly believe that this depiction was in any way

intentional. Most likely, they just couldn’t handle their own 3D engine and

ran out of time and money before they could come up with a better solution. Then again, some of the

game’s bonus content does suggest that there was, after all, a tremendous

decrease in quality during the transition from storyboard to game video —

here, for instance, is the comparison between Cortez as originally depicted

(left), where you can clearly estimate

not only his age, but his Mestizo ethnicity as well, and Cortez as actually

seen in one of the cutscenes (right), where he makes a nice male pair with

April as the happy couple who have just broken out of a mental ward. If it

was all done just for the sake of having smoother and less resource-consuming

animations, I would honestly have been much happier with just a series of

stills, mayhaps in comic-book fashion or something.

The bad news is that for

many people, this quality of the graphics results in an automatic turn-off —

even I notice that I have to make a strong effort of will to distance myself

from these visual images and «mod them» appropriately in my own brain in

order to keep the experience wholesome and enjoyable. In a just and fair

brotherhood and sisterhood of men, The

Longest Journey would not simply be upgraded to HD quality by a bunch of

independent fans, but remade by its own creators, with the character sprites

and cutscenes completely redrawn, while leaving everything else intact. You

may say I’m a dreamer, but I’m not the only one; I hope some day the world...

aw, who am I kidding? The world is too busy playing Fortnite anyway to give a piss about some shitty 3D animations

from more than twenty years ago. |

||||

|

Sound Although there are certainly no hard

feelings about the game’s musical soundtrack, as opposed to some of its

visuals, it is not likely that it will pass on into legend or anything. For

one thing, about 90% of the game features no music at all — just the ambient

sound effects (water, wind, whirling fans, crowd noises, etc.) and the

voicing — and I have no problem with that: given how much Ragnar wants you to

focus on the sound and meaning of the long-winded conversations, it makes

perfect sense that music, especially

well-composed music, would only distract from the necessary experience (the

way it actually does in, say, Grim

Fandango, where sometimes you have to make a quick painful choice about

whether you want to be delighted by that loud brass riff or the latest

Glottis joke). For another thing, once the music does start, it rarely advances past

the acceptable and relatively predictable levels of a high budget Hollywood

fantasy movie. The main theme, which is probably the most memorable one

because you always have to go through with it while loading up the game, is

cozily Hogwarts-like, if a bit darker due to the organs and cellos, and most

of the rest are moody neo-classical ambient-ish pieces that do certainly

contribute to the atmosphere but, so it seems to me, rarely have a strong

emotional pull of their own. At least the good news is that the entire

soundtrack, written by local guy Bjørn Arve Lagim (not much else in

his portfolio), is instrumental — for the next games Ragnar, whom I respect

immensely but who, like most non-musical artists, has shit taste in music,

would drag in some pathetically sentimental crap artists with their indie

hearts on their sleeves, which would sometimes dangerously elevate the

soap-opera levels. The Longest Journey

only moves close to soap opera on a very few occasions, and most of these

have more to do with April going on another clichéd I’M NOT WORTHY rant than with the

music. So enough about the music and on to

what might be the game’s single tastiest attraction — the voice cast. If I

understand correctly, despite the game being produced in Norway, its primary

localization was still English: at least, all of the dialog does look as if

it were initially written in proper English, rather than translated. And as a

graduate of New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts, Ragnar seems to

have had plenty of friends and acquaintances with the proper credentials to help

him with the voicing — at the very least, the fact that Sarah Hamilton also

attended the same school could hardly be a coincidence. Not surprisingly, the

majority of the actors cast in the production were no big stars: in fact, for

most of them their roles in The Longest

Journey were their first (and for quite a few, also the last) experiences

in this line of work. It is all the more amazing, consequently, just how much

Ragnar managed to get out of them — maybe his musical tastes leave a lot to

be desired, but he definitely has a good, sensitive ear for the human voice. Let us begin with a simple statement of

fact: Sarah Hamilton’s performance as April Ryan in The Longest Journey is the single greatest vocal tour-de-force in

the history of plot-based videogames, period. And even if there are still

plenty of plot-based videogames I have never played (or heard, for that

matter), that statement still stands, because there is absolutely no way a

living human being of flesh and blood (and we do have to assume that Sarah Hamilton is a human being of flesh

and blood) can deliver a finer, more nuanced performance than Sarah does. She

can do it all — April as a moody teenager, April as a pensive wannabe-adult,

sarcastic April, scared April, compassionate April, intellectual (or

pseudo-intellectual) April, dumb April, dominant April, submissive April, rebellious

April, forgiving April, heck, even an April imitating an Italian accent when

trying to ruse her way inside her enemies’ headquarters with a box of pizzas.

If, at the end of the game, we still remain a little perplexed with the

character, unsure how to characterize her psychotype and emotionality, this

is entirely the merit of Sarah Hamilton and her many hours spent behind the

mike at Funcom. Yes, there are lines in the game — like there are in every

video game ever made — that make me cringe ("I can’t do it! I’m not who you think I am" blah blah blah),

but it is all the fault of the writer; Sarah does her best to rescue and

redeem even the cringiest ones, and succeeds more often than not. Simply put,

I know of no better example of a voice actor so totally and utterly immersed

into her character in each and every environment and situation imaginable.

And that voice tone — oh my God. You know you’re staring in the eyes of

greatness if you ask your character to look at the shelves in her room, and

all she says is "Shelves",

and then you do it again, and she says "Still just shelves", and you know you could do it again and

again and again, just to keep you happy for an indeterminate amount of time.

That’s right. All it takes is one word. Shelves.

Try it yourself, you’ll never sound as good as Sarah Hamilton. She would later return to voice April —

a completely reinvented April, this time — for 2006’s sequel Dreamfall, and still later, in 2014,

for Dreamfall Chapters (where she

only has a few episodic snippets), but this was probably due to her own

sentimental attachment to the role and / or Ragnar’s personal request,

because she has long since quit her acting ambitions in order to concentrate

on battling various illnesses, «life coaching» and other stuff (her Youtube channel is

more than a little weird and slightly disturbing); I suspect that she’d

always had plenty of inner demons, and that, somehow, they at least did her

one good service by agreeing to fire up the virtual character of April Ryan,

providing her with no less than a legendary alter ego in the process. In

between the two, Ragnar and Sarah managed to show us all what the proverbial

«strong female character» should really mean — not simply the ability to kick

mucho ass and show the dumb males their place (though she is capable of doing

that, too, whenever fate calls), but, first and foremost, realism and multi-dimensionality (which so many Tough Girl writers

comfortably forget about). Oh, and plenty of humor, as well. Next to Sarah’s amazing (yes, I do not throw that word around idly) turn

as April, everybody else inevitably retires into the background; however, the

majority of performances rank from passable to solid, which is, once again,

quite a feat for a cast of virtual unknowns. One major fan favorite is Roger

Raines as April’s sidekick Crow: I would not call his work too outstanding,

as he faithfully follows in the steps of Robin Williams, Steve Martin, and

other comedy greats without developing too much of an individual personality

— but his diction, phrasing, and subtle twists of intonation are beyond

reproach. Ralph Byers, a TV veteran, does a pretty hilarious «evil alchemist»

in his portrayal of Roper Klacks; but in all honesty, I think that the best

comic roles in the game are voiced by Madison Arnold, who brings to life the

totally superfluous, but so-glad-he’s-here sleazy Italian detective Minelli,

the down-on-his-luck Stickman Woody ("you’re a bulldozer with a brain, lady! you’re an accident waiting to

happen!"), and the

story-telling old sailor ("ever

consider doing a book?" – "aye,

but the agents in Marcuria be bloodthirsty vampires with no thought but to

milk your life’s blood" – "oh,

so they take an outrageous commission?" — "no, they actually be bloodthirsty vampires with a penchant for biting

your neck when you ain’t be looking!"). Sorry for slipping into

dialogue-quoting mode again, but it’s just so hard to resist... Note that some of the characters might

easily offend sensitive ears — the almighty hacker Burns Flipper, voiced by

Andrew Donnelly, was probably written by Ragnar after one too many hours

spent on a late 1990s Internet forum, as one of those bulldozing edgelords

whose social skills were blown to smithereens by the digital revolution, and

it does not help that Andrew embraces the role with such gusto that I have no

idea how he never ended up in South

Park. Personally, my ears would

rather be offended by the single obviously miscalculated vocal performance —

Kevin Merritt as Gordon Halloway, the Vanguard’s personal anti-Christ and

April’s arch-nemesis. The idea was to portray him as a completely

de-emotionalized human being, the quintessence of pure cold logic, but while

trying to avoid sounding sympathetic, like Data, he adopts an oddly

cadaverous tone and pacing which make him sound more retarded than creepy or

terrifying, and I think they clearly miscalculated. Ralph Byers does a much

more credible job as his mentor, Jacob McAllen. In any case, if we agree to call the

overall cast of The Longest Journey

«quasi-amateurish», implying that for many of these guys this was their first

professional experience in voice acting (or even acting in general), then

this is unquestionably one of the greatest amateurish performances in

videogame history — and many serious thanks must go to Ragnar (who is

actually credited as Voice Director) for making all the actors believe in his

universe and, consequently, turn out realistic and fully believable

performances all the way through. And if you have just completed the game, be

sure to visit the «Book of Secrets» bonus section for some hilarious vocal

outtakes: to the best of my knowledge, this was the first time ever that a

game actually included a collection of recording bloopers as a gift to the

players — and not only is it silly fun to hear Sarah struggle with the pronunciation

of words like ‘Changagriel’ or hear Abnaxus’ voice artist go "She gave birth to our three female

children, Abratha, Abelexe, and you-gotta-be-kiddin’", but it is generally

intriguing and instructive to get this intimate access to the holy-of-holies,

the recording studio, if only for a few minutes of fun. |

||||

|

One area in which Tørnquist

clearly felt there was not much left to do was the base mechanics of the

gameplay — most of which was copied straightaway from recent LucasArts games.

Thankfully, he did not find it necessary to borrow the idea of the «tank

controls», favored by Tim Schaefer — despite the 3D mechanics, you use the

same good old mouse, rather than the keyboard, to control April on PC, and

she is perfectly willing to rotate around her axis and head off wherever you

wish her to go, so at least in that particular department, Funcom’s game

engine was superior to LucasArts. They did borrow the walk-vs.- run mechanics of Grim Fandango, though (single-click to make April walk slowly, double-click

to make her run, which most certainly helps whenever you have to waste time

on backtracking). Predictably, each screen is loaded with

hotspots which animate your cursor when it lands on them; the hotspots

themselves are divided into «passive» ones (which can only be looked upon,

usually for a bit of trivia or humor) and «active», clicking on which opens a

small, nicely stylized submenu of choices (usually just «look» and «operate»

or «talk»). All dialogue is also structured precisely the LucasArts way —

there is a selection of choices at the bottom of the screen, some of which

are simple questions that yield information and clues about how to proceed,

and some are mutually exclusive in order to let you build up your own

sub-personality for April (more or less polite, more or less sarcastic, that

kind of thing — personally, I think that polite and courteous choices are

boring as heck, and always prefer my April to roast her interlocutors, but

Sarah Hamilton can easily satisfy supporters of both approaches). Travel through Stark and Arcadia is

managed by means of a special map window, though you cannot just open it at

will: in Venice, you are obliged to go to the trouble of always taking the

subway and waiting for a train, while in Arcadia you have to leave a certain

area in order to be able to hop on to another. Since the areas can be

relatively large, backtracking sometimes becomes a pain in the ass (running

from the subway station through what feels like miles of wasteland to Flipper

Burns’ hideout is a particularly irritating memory), but I guess it’s sort of

an inevitable pain in the ass if you do not want the game to feel like a

frickin’ visual novel or something. As usual, it really only becomes a

problem when you’re stuck and desperately running from place to place to see

which particular clue you might have missed. Like the absolute majority of adventure

game designers before him, Ragnar also felt it necessary to break up the

alleged monotonousness of object manipulation-based puzzles with a variety of

«non-standard» puzzles, which are predictably hit-and-miss. Some, like

putting the Disc together by placing its various pieces into the appropriate

slots of the magic circle, are annoying, but simple; some, like putting

together a «telephone line» for Q’aman on the Alais Isle, are actually

inventive and fun to solve; and some are just plain horrid — like the clamp

puzzle early in the game, which is actually a sub-puzzle of the

abovementioned Rubber Duck disaster: in all honesty, I still cannot quite figure out how the water pressure system

works, and I think I either solved it through blind trial and error or

checked a walkthrough, don’t really remember which. In any case, it is clear

that Ragnar is no Charles Cecil when it comes to designing those sorts of challenges,

which is hardly surprising: who can be equally good at building up a complex,

lore-rich multi-verse based on separation of magic and science, and at constructing a switch-based

puzzle to help you remove a clamp from a pressurized water pipe? One useful feature of the game is

April’s journal, in which she painstakingly transcribes all of the latest

events — nice to have because of occasional information overload (Ragnar does

take his lore seriously), and fun to read because everything is indeed logged

diary-style, as bits of original artistic prose; I would have been much more

happy if they had Sarah voice all of the content, but I guess she had quite a

grueling amount of work to do as it was, let alone the fact that Funcom would

probably end in financial ruin if they had to pay her for all that overtime.

The journal feature, by the way, might be one of the few influencing echoes

of Gabriel Knight in the game, what

with Grace Nakimura having kept her own diary in The Beast Within (which she did

voice in its entirety, but I guess Sierra’s budget in 1995 was far more

impressive than Funcom’s in 1999) — of course, journals were already

commonplace in RPGs at the time, serving a purely pragmatic purpose of

keeping you up to date on all the miriads of quests that kept you hanging, but

they were still a relative novelty for adventure games. Finally, the game offers a few nifty

extras, packed together into the nicely titled «Book of Secrets» — such as

the already mentioned collection of voice recording «bloopers»; some

additional music pieces that did not make it into the game, for one reason or

other (including a non-essential, but funny "April Dub", based

around a sample of Sarah saying "weird things have been happening

lately"); and a collection of pre-production graphic art, which is

really sad to look upon because it shows just how much more beautiful the

game could have been if not for the unfortunate premature decision to deliver

it in 3D format (see the image of Cortez in the Graphics section above). Nothing too exciting, but each of the

bonuses is actually worth taking at least a quick look, and that’s already

impressive as far as videogame bonuses are concerned. Overall, I don’t think I have any

serious complaints about how the game works, since it is quite content to

follow the best of the pre-existing recipes rather than experiment for

experimentation’s sake. The single most difficult thing about it today is to

get it to run properly on modern computers — which is why, once again, I have

to recommend the HD mod (which has to

work in conjunction with the ResidualVM emulator, originally developed for

LucasArts games such as Grim Fandango

and Escape From Monkey Island,

released in the same time period as The

Longest Journey) for both better quality graphics and smooth functioning. It will require a bit of patience, though

— those early Windows games are so much more of a bitch to run with modern

software and hardware than the classic DOS stuff, it’s not even funny. |

||||

|

It

wasn’t broke, and Ragnar Tørnquist, of all people, was not in the

least intending to fix it. There is not a single thing about The Longest Journey that I can think

of which would improve on any of the formal

aspects of the adventure game genre as we knew it in the mid-to-late 1990s —

for all I know, nothing short of a return of a corrected and diversified text

parser model instead of the intellectually limited point-and-click interface

could provide such an improvement. Instead, Tørnquist turned his

attention to substance, setting

himself the challenge of overriding the typical limitations of previous

adventure games — simplistic plots, laconic dialogue, insufficient character

personalization, and lack of social and personal relevance. More than

anything else, he wanted his game to have the artistic value of a good movie

or a decent novel — something that games like Gabriel Knight and Grim

Fandango were already approaching in a close-but-no-cigar fashion. So,

does The Longest Journey get the

cigar? No, it does not. Nothing gets the cigar (which is not that bad, really

— I believe that the cigar is at least theoretically «gettable», and,

consequently, that there is at least theoretical hope for the future). There

are too many stale tropes in Tørnquist’s narrative, too many moments

when his sharp and witty sense of irony seems to turn into a cover-up for

lapses of imagination... and then there’s the Rubber Duck puzzle, too, which

is like a symbolic blinking light for all those who insist that a

point-and-click adventure game cannot make logical sense by definition (ah,

but maybe if you brought back the text parser... sorry, I’ll shut up now).

But there can be no denying that the game was a huge substantial step forward all the same. For each of its

flaws, there is an overriding virtue — for each of its cringy moments, there

are long minutes, if not hours, of sheer intellectual and aural delight. I

already mentioned that one of the most startling things about The Longest Journey is that it is, in

fact, the single longest adventure

game up to that point — approximately twice as long as any of the Gabriel Knight games, let alone

others. Some might complain that most of the length is simply due to the

unnecessarily long-winded dialogues, but the main reason is that Ragnar had

two distinct universes to introduce and endear to the player. In the process,

he created a genuine epic tale — something that, for better or worse, did not

really exist in the adventure game genre before him. LucasArts wrote

comedies; Sierra put out small-scale dramas with relatively small concern for

lore, detail, or character development (only Gabriel Knight came close to a true epic, but still lacked the

necessary sprawl to qualify). Next to all those protagonists that came before

her, April Ryan was the Luke Skywalker, the Frodo Baggins, the Harry Potter, the

Siegfried, the Till Eulenspiegel, the Ulysses of the adventure game — and

what’s more, I bet you a sealed copy of the game that none of those guys could say "Still just shelves" with the same

force of expression as she did. Because

of this, it does not really matter all that much if the epic in question was

flawed — most epics, particularly the fantasy ones produced in recent times

by individual authors, tend to be flawed in one way or another. What matters

is that Tørnquist showed us all the right way to go... and nobody

really went there. The Longest Journey

could have been the start of something really big; instead, it kind of

brought the adventure game genre to a sort of massive peak which nobody could

properly top, so they all just went elsewhere. There would still be excellent

point-and-click adventure titles released throughout the 2000s and 2010s, but

this sort of epic vision would not be found within them — instead, it would

be relegated to various RPGs and action adventure games. Not even

Tørnquist himself, with two more sequels under his belt, could beat

his own achievement (I have a soft spot in my heart for both Dreamfall and Dreamfall Chapters, but neither of the two games scales the

heights of Journey, which is

something I will expand on in more detail in their own reviews). In

that sense, The Longest Journey was

its own beginning and its own end — the closest analogy in my other favorite

world, that of rock’n’roll music, would probably be the Who’s Quadrophenia, an epic concept album

that sounds or, more properly, feels

like nothing else done before or since and sort of begs to be imitated

without dropping any good clues as to how it should be imitated. Similarly, The Longest Journey simply benefited

from a lucky, once-in-a-lifetime alignment of the stars, never to be repeated

again. But maybe somebody, some day, might still give it a spin and get

influenced by it the very same way that Ragnar himself was influenced by Gabriel Knight — and then, who knows,

we might yet encounter an adventure game protagonist who will be even more

relevant to the young, neurotic, idealistic gamer than April Ryan in her

underwear, trying to save a dragon egg for fear of suffering seven years of

bad karma. |

||||