|

|

||||

|

Studio: |

LucasArts |

|||

|

Designer(s): |

Brian

Moriarty |

|||

|

Part of series: |

—— |

|||

|

Release: |

January 1990 (DOS) / April 1991 (FM Towns) / 1992 (DOS CD version) |

|||

|

Main credits: |

Programmers: Peter Lincroft, Kalani Streicher Music / Sound Effects: George Sanger (+

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky!) |

|||

|

Useful links: |

Complete

playthrough (104 mins.) |

|||

|

Many

of the finest video games from past decades, whether you revisit them as a

veteran player or (something that happens very rarely indeed) pick them up

out of historical curiosity, not even having been born at the time of their

original release, make you instinctively go, «oh, how I wish this one came

out or, at least, was remade today!»

And it’s not just the obvious matter of better graphics, sound, or gameplay

mechanics — usually it is also a matter of depth and detail, with modern

games allowing players the kind of immersion into one of those fantastic

universes that they could never be offered at the dawn of computer gaming,

when studios were small, writers were scarce, storage space was limited, and

a new game was supposed to provide you with, at most, a couple weeks worth of

entertainment / challenge (well, perhaps up to a month if it were some sort

of sprawling, repetitive, potentially infinite RPG or strategy game). Actual

situations where a classic experience from the early days would be dusted off

and remade in the full spirit of the original, but making full use of modern

possibilities, are very rare in the business — perhaps Resident Evil, whose lovingly crafted remake from 2002 all but

obliterated the need for the original, could be quoted as a textbook example

— but most of us «retro-philes» probably harbor those secret dreams for most of

our old favorites, if only out of a secret desire to pass our preferences on

to our children and our children’s children. There

are, however, cases when I look back at some

of these games and realize that they are perfect just as they are — that any

tinkering with the original concept, style, and laconic presentation will

hardly lead to anything other than cheapening the effect and dissipating the

magic. For instance, trying to transform something like Christy Marx’s Conquests Of Camelot into yet another

modern day episode of Assassin’s Creed

would remove the beauty of telling King Arthur’s story as a sort of simple,

elegant morality tale for children (including that inner child within us

grown-ups, of course); it might still have ended up a good game but it would

be an altogether different, and

probably much less unique title. Hampered by technical limitations, good

designers and writers in the 1980s and 1990s did not employ mere technical

solutions — they came up with their own ways to tell their story and immerse

you in their world, ways that no longer make sense in newer ages of gaming

but now look wond’rously strange and, perhaps, even oddly inspiring when,

like a finely aged silent movie, we approach them with the preconception of

«this feels so different!» rather

than «this feels so old!» No

other game from the Golden Age of Adventure Gaming epitomizes this feel for

me better than Brian Moriarty’s Loom,

LucasArts’ bizarre reimagining of Swan

Lake that, in a sense, remains the «ugly duckling» of the studio, though

perhaps «black sheep» would be more appropriate — the only openly non-comedic

game to come out of classic LucasArts, the only LucasArts adventure game

based on its own universe of lore and the only one to design and implement a

unique playing style that nobody has been able to properly emulate or develop

further ever since. Short, full of gaps and unanswered questions, in some

ways rather more like a demo or sketch than a completed game, it never got a

sequel, it never got a remake, it is largely ensconced in memory as a

dramatic failure (which it never was) — and, for what it’s worth, it should

probably stay right as it is. There is no way I can see to make this

perfect-for-1990-oddity work anew in the totally transformed age of video

gaming; even a simple graphic remastering would be questionable (and I had

absolutely no problems with the remastered graphics of Day Of The Tentacle or even the completely redrawn graphics of

the first two Monkey Island

games). Doubtlessly,

this is somewhat related to the personality of the game’s creator — and, as I

always insist, if you cannot properly align a video game with a specific

creative personality, that game probably ain’t worth a nickel. In this case,

we’re talking Brian Moriarty, an exceptionally bright and «outta-the-box»

alumnus of Southeastern Massachusets University with a degree in English

literature (which does often show) and a combined Steve Jobs-ian passion for

technology and the humanities, though, alas, none of that Steve Jobs-ian

talent for channelling public admiration. Moriarty’s early claims to fame

were his designing and writing for several classic text adventure titles for

Infocom — such as Trinity and Beyond Zork — but with the text

adventure market pretty much evaporating by the late Eighties, he had to find

a different outlet for his talents, and ended up at LucasArts, to which he

dedicated five years of his life — all of it resulting in one semi-finished

game that you can complete within 1-2 hours of gameplay (Loom) and one failed project which he ultimately had to give up

to other designers (The Dig, which

only saw commercial release two years after Moriarty’d already been gone from

the company). Since

absolutely nobody except for battle-hardened Gen X veterans (myself excluded

— I was born just a wee bit too late for that) plays text adventure games

anymore, and since Moriarty’s post-LucasArts career has concentrated far more

on writing and lecturing than on game designing, Loom is pretty much the only title he may count on being

remembered for — but even that one title is more than enough to be

remembered. It was neither «behind its time» nor «ahead of its time»; more

properly, it was «out of its time», a bizarre experiment heavily applauded by

the critical community and, for that matter, not exactly underappreciated by

the market — at the very least, it sold well enough to redeem its budget,

which was all that was required at the time to let you stay at LucasArts (don’t lose money and don’t embarrass George were the two

chief directives for everybody working in the company at the time — ah, the

Golden Age!). But

even though it ended almost literally in mid-game, the proposed sequel never

materialized — perhaps because, as it happened in the musical world to people

like Brian Wilson and Pete Townshend, the artistic ambitions of its author

ultimately proved too heavy and/or too confusing to smoothly get off the

ground. There might have been a way

to properly expand the fantastic universe created by its author, to build up

on the ideas for its musical background and gameplay mechanics, but neither

Moriarty himself nor anybody else was able to find it or implement it.

Although Loom was certainly not

the only LucasArts game to have never received a sequel (the same fate befell

Zak McKracken, for instance), it

became a proverbial example of a revered

and outstanding game not to receive

a sequel — going as far as to become a regular target of in-game inside jokes

for the studio, from the «ask me about Loom» running gag in the Monkey

Island games to the cheesy, but accurate exchange between Guybrush

Threepwood and Captain LeChuck in Curse

Of Monkey Island (Guybrush: «If you

kill me, there’ll be no more Monkey

Island sequels. No sequels means no work for you. You’ll become just

another has-been that nobody’s heard of.» LeChuck: «Ohhh! That could never happen to ME! I’m LeChuck!» Guybrush: «Do you know the name "Bobbin

Threadbare"?» LeChuck: «Uh, no».

Guybrush: «Exactly».) Apparently, there were plans for a sequel — in fact, Moriarty, staying well in line with the strategy of his company’s founder, envisioned Loom as a trilogy, with two subsequent parts that were to be called Forge and The Fold, respectively, but the first of these never went beyond a basic planning document, and the second left behind nothing but the name. (A curious Italian-based fan project tried to resurrect Forge about two decades ago, but wound up abandoned with just a demo version of the first chapter, and what I’ve actually seen did not really look too promising anyway). Given that Loom, in its finished form, ended up pretty tiny compared to even contemporary LucasArts games, and yet Moriarty complained about creative and physical exhaustion after the title finally shipped, this is hardly surprising. What is surprising, or at least what is a bit of a puzzle worth looking into, is how such a short and almost minimalistic game could have resulted in such an exhaustion. Was there really something extra special about Loom, something that required spending two or three times the amount of artistic mana as compared to the usual line of product delivery — or was it all just a big and hollow put-on, a bunch of empty, dead-end ambitions that resulted in a stillborn oddity rather than a unique, inimitable masterpiece? This is what we’ll be trying to understand over the course of the ensuing review — so let’s get to it. |

||||

|

Content evaluation |

||||

|

Brian Moriarty’s ambitions as a storywriter for the video game

market go back to a much earlier period than Loom — his text-based Trinity

for Infocom was, after all, about altering time and space in order to save

the world from nuclear apocalypse — and there can be no doubt that he was

specifically hired at LucasArts to try and find a somewhat more serious angle

for the studio than the goofy, sarcastic fun style it had become tightly

associated with ever since Maniac

Mansion had established LucasArts as a serious challenge to Sierra’s

monopoly on graphic adventure games. Loom

is certainly not devoid of humor — there are plenty of sarcastic one-liners

and inside jokes to make the player smile — but it was, indeed, the first

LucasArts game to date where humor, satire, and goofiness were not the chief

focus of the designers. Instead, Moriarty made an attempt to flesh out a story that,

while essentially sticking to the common gaming trope of the

save-the-world-from-evil-boss type, could draw the player in with its own

unique fantasy universe, the kind of thing that was relatively common in RPGs

but not so much in adventure games. Of course, Sierra had King’s Quest for the fairy-tale nerds

and Space Quest for sci-fi nerds,

but both of these franchises were there mostly for the basic story, the

puzzles, and (in the case of Space

Quest) some good laughs. Meanwhile, Loom

was there for the vision — the grand

vision, as it were. Previous adventure games skirted around the idea of

epicness, borrowing motifs, characters, and occasional phrase turns from epic

folklore and literature; Loom was

to dive into the world of EPOS head first, taking the same kind of risk that

George Lucas had done with Star Wars

twelve years earlier. As in all of the allegedly «original» fantasy universes

submitted for our approval over the past half-century or so in all the areas

of artistic creativity, Loom is

mostly a synthesis, taking its inspiration from sources as far removed from

us as Greek tragedies and epic poems, and as close to us as the latest Star Wars and Indiana Jones movies (this is

LucasArts, after all). Somewhere in between lies such an odd source of

inspiration as Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake,

appropriated for its transformation motifs rather than its tragic romance

(the one thing that Loom either

did not have time for, or did not care about in the first place). Yet despite

all the influences and borrowings, the universe of Loom has its own patented structure, and the major plot engine of

Loom — the idea of integrating the

motifs of weaving and music-making — belongs exclusively to

the mind of Mr. Moriarty. Take O’Shaugnessy’s (and Willy Wonka’s, and Aphex

Twin’s...) famous "We are the

music makers / And we are the dreamers of dreams / Wandering by lone

sea-breakers / And sitting by desolate streams / World-losers and

world-forsakers / On whom the pale moon gleams / Yet we are the movers and

shakers / Of the world for ever, it seems" — then change just one

word, dreamers, to weavers, and there you have it: the

meaning of Loom in a nutshell. Even an abbreviated retelling of Loom’s entire plot would take too much space; there is quite a

lot that happens over its less than two hours running time, and what is not

there directly in the game had to be crammed into a 30-minute audio Prologue

that actually came packaged together with the disks as an additional audio tape

(!). To single out just the main points, the whole thing takes place in some

ultra-distant future period, when, after the collective actions of Trump,

Putin, Taylor Swift, Elon Musk, and people who invented words such as

«vlogging» and «microtransactions» (sorry), the world as we know it has

effectively collapsed — perhaps several times — and the remaining survivors,

in order to ensure the most efficient way of prolonging their survival, have

become segregated into small professional communities, the Guilds, with each

Guild reaching the ultimate perfection in their particular skill,

occasionally even crossing into the supernatural. Why exactly this strict

division of labor (presumably, with a decent bartering service set up among

the different Guilds) has helped humanity survive better than any other

remains a mystery, but it did

result in the Guild of Weavers managing to tap right into the very fabric of

the universe, with their Great Loom almost taking on a life of its own and

capable of producing unpredictable, baffling, and occasionally dangerous

patterns (hello, ChatGPT!). For this, the Weavers were banned to a remote

island, where, seemingly, they have been spending the last thousand or so

years of their lives trying to contain their little nuclear Loom. What happens next, both within the audio drama prologue and the

first 10-15 minutes of the game itself, is fairly chaotic and does not always

make perfect sense, but does have a little of that Promethean vibe to it as

several solitary characters oppose the conservative values of the community

and rebel against the natural rhythm of Fate. The result of all that

disruption is... you, «Bobbin

Threadbare», The Chosen One, who watches the entire Guild being mysteriously

transformed into a flock of swans and evacuating the island, leaving you to

make your own journey, on which you must try to (unsuccessfully) reunite with

your brethren, (also unsuccessfully) stop a power-hungry madman from

releasing Chaos, and ultimately watch the world being torn in two halves

where you can sort of save one and leave the other one to Chaos... ...okay, to be honest, I think that the plot in its

most monumental, epic layers is not a particular achievement that Brian

Moriarty could truly be proud of. For an «out-of-the-box» type of writer,

there is really too much in Loom

conforming to classic stereotypes — such as the usual corrupt antagonist

deluding himself into thinking that he can exercise control over the

primordial Evil (I suppose that, want it or not, the entire LucasArts studio

revolving around the Indiana Jones

themes at the time did rub off on Mr. Moriarty), or the usual Chosen One Gotta Save The World Because

Those Who Are Supposed To Be Wiser Than Himself Are Really All Complete

Idiots trope. It’s all very twisted and convoluted, with an entire heap

of lore poured over your heads across the game’s less-than-two-hours playing

time, and lots of baffling internal contradictions about which you could not

even say whether they are careless plotholes or not, because the whole thing

is so short anyway that it requires your own imagination to fill those

plotholes in by definition. In other words, while Moriarty did manage to create

a somewhat unique fantasy universe based on an interesting premise (the

Guilds as the main structural cells of humanity, rather than the usual

economic and cultural add-ons as they are usually seen in everything from Dune to D&D) and an intriguingly

colorful (or, more acurately, colorless)

protagonist, he was either unable or unwilling to deliver an equally

interesting storyline that would make ample use of this premise. Over the

course of two or so hours of gameplay you manage to uncover and, if not

exactly defeat, then at least

sabotage an evil plan for world domination, but it still feels like a

slightly bloated first-draft pilot version that any movie executive would

probably return with a bored "yeah,

so?.." kind of reaction. Even the main villain has essentially one big scene all to himself and is

seemingly dealt with for good before we can properly establish his

motivation. The miracle of Loom,

therefore, is not that it has a great fantasy narrative (it does not), but

that it manages to work so well in

spite of the mediocre narrative. The dynamics of that universe do not

truly matter; what matters is its bizarre constituency — the images, the

sounds, the basic mechanics of everyday life. If the grand scheme is

disappointing — it just goes to show you that heroes are heroes and villains

are villains all over the multiverse — the peculiars are anything but. |

||||

|

Puzzles

You do, of course, communicate with other NPCs met along the way

in words — but apart from the usual «exhaust all possible dialog options»

requirement that is occasionally necessary to advance the game, everything

else in the game is achieved through the use of the protagonist’s magical

musical distaff. (To be honest, the distaff in question looks more like a

regular magical staff rather than, per definition, "a device to which a bundle of natural fibres (such as wool, flax, or

cotton) are attached for temporary storage", but since we’re talking

Guild of Weavers, clearly they couldn’t just do with a regular staff). The distaff functions as a primitive, but

powerful musical instrument, upon which the protagonist can cast series of

musical notes — each combination corresponding to a command or spell, except

that you have to learn these spells along the way, and only a few notes are

open to you from the beginning; as you progress and gain more experience,

additional notes open up, allowing for more flexibility. One could argue that this is simply a more sophisticated (and

pretentious) way of encoding the exact same commands that you used to type in

in parser-based games, or select from the list of verbs in LucasArts’ classic

early titles. Thus, producing the musical sequence E-C-E-D is essentially the

same as selecting "open"

from such a list, except that it takes more effort to remember the damn thing

and more time to execute it. But, in fact, the ability to «dissect» a command

into a sequence of notes opens up a whole new way of looking at it —

although, unfortunately, the game only capitalizes on this opportunity in one

aspect: most of these musical «drafts» work both ways, so if you need to open something by casting E-C-E-D,

this means you can close it by

casting D-E-C-E, and so on. This is something the player has to keep in mind:

the game lets you directly learn each draft only in one direction, so when

the time comes to do the right thing, you have to remember the general

principle and experiment with your drafts by casting them backwards.

(Ingeniously, those few drafts that have no imaginable «reverse» variant,

like Heal or Reflect, are encoded with palindromic note sequences). Needless to say, this musical language could have been so much

more — or, at least, could have been taken to further and further heights in

subsequent titles, had the game ever stood a chance of living on. Associating

notes with different elements, or different magical spheres, or different

emotions, etc., could have led to truly opening up a new reality for

adventure games, making your brain switch to a seriously different pathway of

encoding and decoding information. Yet there are also limits to how much

pressure the average brain of the average player can withstand — and a

serious red line between the realms of creative entertainment and educational

headache. Loom never really

crosses that line, only hinting at the true otherworldliness of the game’s

puzzle mechanics that could be; yet even that small hint is enough to

solidify the impression that you are truly navigating an alternate reality

where everything you’ve been previously used to is different. The actual puzzles are not too difficult, as there is a limited

number of «drafts» to weave and an even more limited number of hotspots on

the screen to cast them upon — even so, the player might occasionally find

oneself stumped when a certain operation requires two or more different

drafts to carry out (particularly if one or more of them are «reverse»

actions that have not been tried out previously). Fortunately, most of the

actions are fairly rational and logical (in stark contrast to something like

Monkey Island), and a few of the

puzzles are examples of simple and elegant intellectual brilliance (like the

way you have to deal with the Sheep to save them from the Dragon, or with the

Dragon herself after she abducts you instead of the Sheep). Only at the very

end of the game does the course of action start to drift into an absurdly

surreal direction, along with the plot itself, but by that time the game

practically walks you through on its own anyway. Every once in a while, you have alternate pathways to resolving

complex situations, but not too often; the game could certainly have used

more of those, as well as more red herrings and side options, just to let the

player truly taste the potentially infinite possibilities of the «musical

approach» — however, LucasArts’ stringent budgets always prevented the game

designers from going all the way, and in some respects, their «user-friendly»

approach to player interaction paid off worse than Sierra’s parser (for

instance, Sierra’s programmers did not have to bother with graphic encoding

of hotspots, at least, not until they fully embraced mouse controls).

Theoretically, you can try out any draft on any object, but most of the time

you will simply get generic failure responses. The fact that you can play the game on several levels of

difficulty — either with the notes being marked on the distaff or without any

markings, forcing you to learn and reproduce the drafts by ear — does not

make the game particularly more complicated, rather simply more tedious for

those of us without a good musical ear. In the end, it’s all about the idea

rather than its perfect realization, which, granted, would be fully

forgivable for a pioneering effort. It is the inability to capitalize on this

invention that makes me more sad than Loom’s

own limitations. |

||||

|

So perhaps the story told through Loom is confusing and trope-ridden, and the puzzles of Loom are relatively few and simple

(in spite of the groundbreaking mechanics of their realization) — but even

so, there was nothing else like Loom

back in 1990, and from a certain viewpoint, there is still nothing else like Loom even today. Of course, fantasy world building was

hardly a new thing in video gaming after ten years of Ultimas, King’s Quests,

and Might And Magics; however, in

the Sierra On-Line vs. LucasArts-dominated adventure game market, a

full-fledged original fantasy universe with its own lore and ideology was, at

that time, still a relative rarity — such things were usually thought of as

the RPG domain, and RPGs were still strategically-oriented experiences rather

than the cinematic mastodons they would become in the next century (see

something like Ultima VI or Might And Magic 3, released around

the same time as Loom, for

comparison). Although

all of LucasArts’ own previous games could technically qualify as «fantasy»,

they weren’t really high fantasy — most of them expanded either on

pre-existing universes (Indiana Jones;

the Caribbean pirate fantasy of Monkey

Island) or on pre-existing cartoonish tropes (Maniac Mansion with its «mad scientist lab» setting). By

contrast, Loom was neither parodic

by nature nor directly based on somebody else’s foundation. Instead, it was a

brief, but fulfilling fantasy Odyssey, taking the player through at least

four visually and atmospherically different realms before uniting them in a

single fate. But even better than that, it was a bit of a psychological,

melancholic, slightly sentimental Odyssey, one that actually invited you to identify

with its character and see the world through his «mystic eyes», rather than

just use him — like King Graham — as a mechanical vehicle to guide you

through its vistas and puzzles. After

all, when a game opens to the proverbially romantic sounds of Tchaikovsky and

a dazzling vista of seaside cliffs under a multi-colored sunset — and when the very first action you,

the player, are free to make by contemplating a lonely brown leaf hanging

from a nearby barren branch, with the sad laconic commentary "Last leaf of the year..." as it

slowly topples to the ground, never to be seen again, well, one might argue

that there is already more atmosphere in those opening few seconds than in

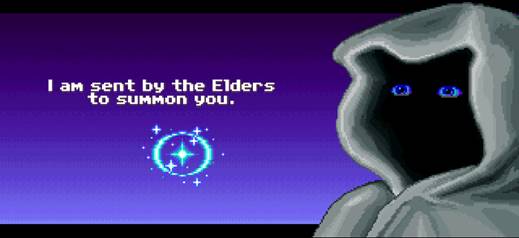

most preceding or contemporary games. Oddest of all is the protagonist: cloaked,

hooded, with indigo-blue eyes intensely peering out of an unseen face, like

some sort of Invisible Man, but armed with mystery instead of mischief. We

did play for somebody visually similar in Sierra’s Manhunter series from around the same time period, but the

protagonist in those games did not have much by way of personality.

Meanwhile, Bobbin Threadbare is essentially a child in his formative years —

a little naïve, somewhat smart, very inquisitive, and just a trifle

sarcastic — and this combination of uncomfortably spooky appearance with a

sensitive and empathetic nature is quite startling. The

inquisitiveness comes in handy once Bobbin learns of his destiny and sets off

on his personal Odyssey. The initial setting of the game — the Weavers’ Guild

itself — is somewhat of a cross between a Northern tribal settlement (all

those yurts set up on the shore) and an ancient Greek pastiche (upon entering

one of the yurts, you somehow end up in a temple with majestic columns and

all the works). From there, Bobbin transitions to the Guild of Glassmakers,

all of it Emerald City-green and elegantly futuristic; the Guild of

Shepherds, all predictably pastoral and united with Nature; and the Guild of

Blacksmiths, industrial as hell to its red-and-gold core. Bobbin’s

interactions with all of those environments and the people representing them

are usually laconic, but he does manage to make at least one new friend in

each, and through their short cutscenes they even manage to establish their

own personalities — the Wise Advisor from the Glassmakers, the Sweet Young

Potentially Romantic Interest from the Shepherds, and the Young Boy Sidekick

from the Blacksmiths. (They never really get to fulfill their actual

functions, but we can all dream on). All

of these locations and characters feel strangely wispy and dreamy, more like

symbols or allegories of something than actual agents of the plot, and

together with the music, this really makes Loom feel more like an allegorical dream than a proper

legendary-hero-saves-the-world piece of fantasy. Very rarely do you actually

experience a sense of concrete purpose while playing — yes, you know that

technically you are searching for the swan-transformed members of your Guild,

but you barely understand why they were transformed, you have no idea where

they are, and most of the time you’re too busy solving other problems anyway.

You solve puzzles, learn and use musical drafts, talk to people, sometimes

trick people, and your own motives in all this usually remain vague and

confusing. Maybe this was unintentional — maybe Moriarty just kept stumbling

and groping in the dark himself — but as far as I’m concerned, he did achieve

the finest result of them all: where others would have generated sheer nonsense, he somehow produced mystique. Do not

be mistaken, though: Loom is not a

cuddly one for the kiddies. Bobbin Threadbare may exude a child-like

innocence, but there is a crucial scene in the game when his jailer,

intrigued by tales of the Weavers, demands to look at his unhooded face in

exchange for a favor, which Bobbin rather casually agrees to. We never know —

other than an off-screen scream — what ensued and in which particular way the

jailer did confirm the «no man can see my face and live» legend of Bobbin’s

ilk, but we can certainly tell it wasn’t pretty. (Note: in the inferior talkie version of the game, as well as in

the bonus addendum to the original if you played on the hardest level, you could see what happened, and it was a

little disappointing). Bishop Mandible, too, is quite viscerally eliminated

by Chaos — and then there are all of Bobbin’s friends who end up dead or at

least disembodied by Chaos and his minions. Much of this was terrifying by

1990’s standards, and with a little immersion, some of it can still feel

terrifying even today. The borders between gorgeous fantasy dream and bloody

nightmare are really thin here, though, fortunately, the nightmare aspects

are never realistic enough to become properly traumatic. Returning

to what I started out with in the opening paragraphs — about how certain

things can only work well in a retrospectively antiquated setting — all of this weird atmospherics is only

kept alive by the laconic and (unintentionally) «primitive» character of the

game. Bobbin’s short replicas; the general brevity of the game’s dialogs; the

relative quickness with which the player travels from one area of the world

to another; the overall simplicity of the puzzles — what all these qualities

do is they kill off any possibility of «pretentiousness» or taking this whole

thing more seriously and realistically than it should deserve. (A major

reason why the talkie version of the game works worse than the silent

version, which I shall explain more in the Sound part of the review). Instead, the sparseness and primitiveness

emphasizes the game’s «dream» nature, as well as its child-like properties. There

is, indeed, a lot that Bobbin Threadbare and his much luckier contemporary,

Guybrush Threepwood, have in common — the famous "ask me about LOOM"

running gag of Monkey Island is

not merely a fortunate chronological coincidence — such as their combination

of wit and naivete, kindness and sarcasm, insatiable curiosity about the

strange world(s) surrounding them, and occasionally childish behavior. But

Guybrush, for all his attractiveness, is a meta-parodic post-modern

character, whose primary function is to deconstruct the surreal

reconstruction of the universe around him. Bobbin has no such mission; his

ordeal is to fix things rather than tear them apart, though greater forces at

play eventually show him the futility of all this small-scale work. In fact,

if you sit back and start overthinking the effect of the game, Loom eventually takes on the form of

a great tragic metaphor — the story of an innocent kid who wants to do simple

good in the world, but ends up as a cogwheel in the hands of its evil

masterminds, or just as a helpless victim of Fate. This is really more

Oedipus than Guybrush Threepwood — given all those subtle references to Greek

mythology in the Weavers’ Guild, I’m sure the analogy must have been right

there in Moriarty’s mind. Looking

over this section one more time, I fear that it came out confused and

confusing, but that is very much in keeping with the game itself, so I’ll

probably leave it like it is. It does

take a sensitive and discriminating approach to perceive Loom as a one-of-a-kind tiny romantic gem lost on the vast

prairies of digital fantasy worlds; players who are more concerned with vast

amounts and internal coherence of lore might very well find themselves

frustrated and disappointed. But perhaps when the world finally crashes and

burns and all you have left is a couple hours’ worth of electricity for your

PC, booting up Loom might be a

suitably appropriate way of saying goodbye. |

||||

|

Technical features |

||||

|

The original Loom was

published as a DOS game in early 1990, at which time it was still limited to

16-color EGA graphics. That version, simplified and pixellated, is still

available and very much playable; however, comparing it with the CD-ROM-based

VGA versions that came out for FM Towns (in 1991) and then again for DOS (in

1992) leaves little doubt in my mind that the game works much better with 256

colors than it does with 16, and that it simply had to be downgraded

originally due to budget limitations. (VGA titles for DOS did not begin to

ship properly until late 1990, I

believe — King’s Quest V, one of

the first groundbreakers, came out in November, with Sierra always being at

the forefront of graphic innovation — but the VGA standard itself had been

introduced as early as 1987; it simply took some time for it to reach the

mass market). I

have come across more than a few remarks from veteran players about how the

original 16-color version of Loom

actually looks better than the VGA rendering, and all I can say to that is

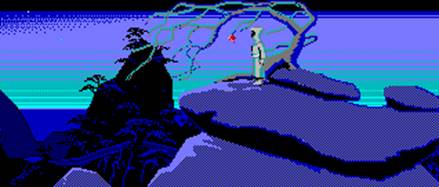

that nostalgia is a hell of a bitch. Here, for instance, is a screenshot from

the early AMIGA version (same EGA as the DOS version) corresponding to the

one from the VGA version reproduced above:

You

can certainly see here how the artists honestly tried to convey the strangeness and «warped reality» of the

universe here with 16 colors — the interaction of the various blue components

in the sky section, combined with the subtle gradations of unbroken and

dotted lines on the horizon, is impressive, as is the stand-out of the

reddish «last leaf of the year» against the overall cold blue patterns of

trees, rocks, and the seascape. But it has nothing on the corresponding VGA

image, which is just a perfect example of the early days of «scenery porn» if

there ever was one. In there, we actually see a gorgeous sunset, reflecting purple on the water and casting a

rainbowish perspective on the entire horizon. The rocks are gray and barren,

while the trees next to them have an odd deep purple glow — not even clear if

that is their natural color or if it is all a trick of the very special light cast on the world

of the Weavers. Admittedly,

I deviate here from the opinion of Brian Moriarty himself,

who, like the honorable purist he wants to be, defends the EGA version to the

death, pointing out how its visual creativity could not even begin to exist

with the technical limitations it had to circumvent. He believes that the

limited color palette was a major bonus to Loom’s atmosphere — that, for instance, if we see all of the

Weavers’ Guild in different shades of blue, with none of those yellow or red

additions, it probably adds to our impression of it as a cold, dark, sinister

location. But why should it be so? The Weavers’ Guild has no obligation to be

wedged in some sort of frozen tundra, nor does it have to give out a 100%

impression of impending death. By adding more colors and skilfully mixing

them, the VGA version succeeds in making the universe of Loom a more vibrant place on the whole, and, where possible, an

even stranger place than it looked like in the original version. I can

certainly understand Moriarty’s bitterness about the fact that the VGA

remasters were made without his supervision, but that does not exactly

elevate his rants above the status of «petty bickering». (The complaints

about cutting out the original game’s content in the «talkie» version, on the

other hand — now that is something

I can get behind; we’ll talk more about it in the Sound section). Anyway,

one thing that both the EGA and VGA versions do have in common — arguably the

single most important visual touch in the game — is the stark color contrast

between the different Guilds. After all those deep blue and purple hues of

the Weavers, Bobbin makes his way to the Glassmakers’ Guild, which is all

about different shades of green, coloring assorted futuristic geometric

shapes — the realm of cutting edge technology! — then it’s off to the

Shepherds, where the landscape, obviously, is also green, but a more natural

shape thereof — then there’s the industrially-tinged Blacksmiths’ Guild, all

about different shades of red and yellow and black (even the skyline is red!)

— and, then, finally, there’s the island and castle of Bishop Mandible, again

returning to green, but this time in a sickly, rotting corpse-like shade of

green. Then, of course, Chaos takes over, and it’s all about a pervasive

blackness threatening to engulf all those lively (or not so lively) colors.

In the end, there is probably more color symbolism in this game than just

about anything produced in any video game up to that point; you could write a

whole thesis on the subtle coloring nuances in the EGA and VGA versions. Finally,

one more seductive aspect of the visuals are the close-up portraits for

different characters: whenever one of them gets an unusually long piece of

soliloquy, the overall perspective is replaced by a face (slightly animated,

though usually just with two or three different frames). This is important,

since character sprites in the game are, as was usual for the epoch, nothing

to write home about, and the portraits do a good job of bringing the various

NPCs back to life. Needless to say, these guys, too, look much better in their

VGA versions than in 16 colors. Special prize goes to Steve Purcell for

making all the Weavers look distinct from each other despite having no faces

— sheerly through the different expressions of their uniformly blue eyes

(inquisitive, pleading, threatening, it’s all in there). This was actually

LucasArts’ first serious experience in the digital portrait craft (with The Secret Of Monkey Island heavily

stepping on its tail), and they immediately bested their chief competitor at

it — in Sierra On-Line, close-up portraits of characters had been introduced

as early as in Leisure Suit Larry

(for, uhm, fairly crucial reasons), but up until that time, they rarely had

the same level of expressivity. With

this additional icing on the cake, it is no wonder that Loom, be it in its original EGA incarnation or the redrawn VGA

version, remains an unchallenged masterpiece in the visual art department if

we’re talking late Eighties / early Nineties. Put it on a 1920x1080 modern

screen, or even on a 4K one, and it still looks classy, even with all the

pixellation. |

||||

|

Sound

And yet, video games are not like any other medium, meaning that

on the whole, the choice of Swan Lake

was not just totally appropriate — it was pretty much a perfect choice on Moriarty’s part. Arranged by George Sanger

(who, within LucasArts, was previously responsible for the NES version of Maniac Mansion), the MIDI melodies

sound lush, resplendent, and just about ideal for complementing the «magical

reality» of Loom’s universe. While

the story of the game does not really have much in common with the narrative

of Swan Lake, apart from the swan

transformation motif itself, the fairy-tale setting clearly does. But perhaps

the most important function of the musical backgrounds — which, as was common

with LucasArts games at the time, play all through your gaming time unless you

decide to turn the music off — is that it alleviates and dissipates any fear,

unease, or discomfort you might experience while wandering through these

strange lands. Even when the game is at its most (officially) terrifying,

after the appearance of Chaos, the music never lets you forget that you are

enclosed in a fairy-tale dream rather than a grim virtual reality with

emphasis on reality. Had the composer been told to create an actual new soundtrack for the game, taking

his cues from John Williams or any lesser contemporary figure, he would

probably strive to adapt the melodic arrangements to their respective

environments — for instance, come up with something «tribal» and

«ritualistic» for the exteriors of the Weavers’ Guild, something harshly

«industrial» for the Blacksmiths’ Guild, and something «spooky» or «martial»

for the sections involving Chaos. Instead, the challenge was to find the most

suitable themes from the ballet for each sequence in the game — a challenge

that is impossible to stand up to perfectly by definition, but whose very

imperfections can result in unpredictable, out-of-the-blue mood swings that

might end up giving the game more character than taking from it. So maybe the

already mentioned match between Little

Swans and the Glassmakers’ Guild feels weird; but using Pas de trois for the main theme of the

Weavers’ Guild makes a fine contrast with the relatively dreary-looking

landscape and gray yurts of the Weavers, constantly reminding the player

that, despite the deceptively drab surroundings, you really find yourself in

a place of delicious magic. Of course, to ensure the proper experience, you have to

experience the soundtrack at its fullest and mightiest; early versions won’t

do, and even the original Roland MT-32 recordings for the PC sound rather feeble

and whiny. This

version, taken from the 1991 FM Towns edition of the game, is arguably the

richest in texture, which automatically means that the FM Towns version is

the one most recommended for any retro playthroughs (it is unclear why anyone

would want to listen to the soundtrack on its own, though, other than a

one-time curiosity... well, to be fair, I’m not sure why anyone would want to

listen to Swan Lake on its own

anyway, be it a classical recording or a MIDI conversion, but feel free to

dismiss this feeling as a side effect of typical Russian snobbery). The FM Towns version does lack the feature that many modern

gamers would find welcoming — voiced dialogue, which would only be added a

year later for the DOS CD version. Unfortunately, as nice as it would have

been to hear Loom voiced properly, this was not the case;

budget limitations caused only a small part of the game’s script (which was

not all that large to begin with)

to be provided with voiceovers, meaning that many lines were simply cut out

of the game. The voiceovers themselves were not terrible (as people sometimes describe them in retrospective),

but rather ordinary, submitted

mostly by a bunch of no-names who delivered their lines, got paid, and went

home — detracting from the game’s magic rather than adding to it. To be

frank, even Indiana Jones And The Fate

Of Atlantis, also released in 1992, featured a more convincing voice cast

despite LucasArts’ relative inexperience with the technology. This is why, in the end, I think that the FM Towns version of

the game is definitive: it has the juicy reworked VGA graphics, the complete

(text) dialogue, and the richest

musical accompaniment — without the

generally dull voiceovers. This does not mean that the game could never have

worked with voicing; it’s just that back in 1992, voice acting in video games

was still in its infancy. Both Sierra and LucasArts would not score their

first true voiced masterpieces until one year later (this would be,

respectively, Gabriel Knight: Sins Of

The Fathers and Day Of The

Tentacle); Loom ended up being

merely the training grounds for the studio, and the actors, who probably

never played the original silent version and had no contact with the game’s

original designer, never got to really get inside Loom’s

one-of-a-kind universe. Which, in the end, is not very surprising: Loom is a game explicitly designed

for the pre-talk era of video games, and trying to voice it was much like

those few failed attempts at transforming a silent movie into a «talkie»

around 1929–1930. |

||||

|

This last section of the evaluation is going to be very short:

talking about Loom’s gameplay

interface and mechanics is barely possible because the game has none. Well, at least in its earliest

part, when Bobbin is still geting his bearings around the Weavers’ Guild — at

best, all you can do is click your mouse on various hotspots, some of which

will give you a slightly enlarged image of an object in the bottom right

corner of the screen, accompanied with a short general description. That is all you get for a while. No parser, no

list of verbal commands (the most typical interface for LucasArts at the

time), no way to operate on or interact with any details of the environment.

Pretty sure that those players who were too lazy to read the manual (usually,

that includes most of us, doesn’t it?) temporarily ended up stumped, asking

themselves if they’d accidentally picked up a buggy copy of the software. Once you pick up your distaff, about 10 or so minutes into the

game, things change — there is your interface at the bottom of the screen,

consisting of... your distaff. If you’re playing on Expert mode, this is the

only thing you see — a stick, various parts of which you have to click in

order to trigger different notes (by ear!). If you’re on lower difficulties,

you’ll also see an accompanying musical staff (no pun intended), making

things a little easier. You don’t even have any inventory: Bobbin is allowed

to handle one on-screen object or person at a time, and carries absolutely

nothing except for the distaff (perhaps this is somehow meant to reflect a

specific type of stoicism common to the Weavers?). This record-setting minimalism (for an adventure game, at least)

does carry a toll in that the game becomes extremely easy to beat, as long as

you meticulously pay your pixel-hunting dues (not too difficult, since the

number of hotspots is seriously limited as well) and diligently jot down all

the musical drafts uncovered on your journey. But challenging the player was

hardly a big priority for Moriarty in the first place — his prime ambition

was to offer the player a brand new language

of interaction, mastering which would become a challenge in itself. And since

Loom, metaphorically speaking,

represents the «childhood» stage of Bobbin Threadbare, it stands to reason

that its musical language also barely advances beyond the «childhood» stage —

even though already at this juncture, it shows you signs of linguistic

creativity when you have to understand and employ in practice the principle

of «draft reversal», producing patterns that nobody explicitly taught you

before by applying analogy and just a little bit of semantics. If I’m cracking this right, any sequel to Loom would have probably featured a slightly more complex and

advanced interface — representing the «adolescent» or «adult» stage compared

to the «toddler» state of the first game — perhaps not merely limiting itself

to more specific drafts, but thinking of ways to weave them together into

more intricate patterns or something of the sort. Alas, with Moriarty’s

universe pretty much «throttled in the cradle» before it could be fully

developed, we can only guess where such a path could have ultimately led. |

||||

|

If you have never

played Loom and somehow this

review ends up stimulating you into getting it and playing it and you end up

disappointed and bored, well, there’s nothing to be ashamed of. Some works of

art make an immediate impression, while others require a modicum of

self-nudging — which may or may not be worth the effort, depending on how you

feel about it. And Loom requires

quite a bit of self-nudging, even outside of the fact that it looks back at

you out of 1990, an age in which digital fantasy universes commonly required

you to fill in the gaps from your own mind, providing more of a stimulus for

imagination than a self-sufficient picture. The worst mistake you can make

about Loom, though, is to treat it

like any other story-driven video game — that is, judge it on the merits of

the complexity and originality of its plot (not a wise solution) or on the

sophistication level of its gameplay mechanics and puzzles (definitely not a wise solution). First

and foremost, Loom is a series of

interwoven visions, combining text, graphics, and music to paint an alternate

reality that you investigate through the blue eyes of your own impenetrable

ghost-child alter ego. Where every other adventure game before Loom used the environment as a

setting for puzzle-solving and role-playing, Loom is the environment

— and your psychological reaction to being part of it. It is the very first

game in the adventure genre (perhaps the very first game, period?) that actually tried to put

the Art into the «art» of videogames; I certainly wonder what the late Roger

Ebert would have to say about this one if they showed it to him instead of

all those really

dubious examples from Kellee Santiago. Of course, in the end Loom is only a faint glimmer of what

could have been — the computer game analogy of a hypothetical 5-year piano

prodigy who tragically died of measles the next week after delighting his

first big audience at Carnegie Hall. But it is still a unique faint glimmer, a tiny peek through a particular doorway

that has never been enlarged or flung open after the death of the initial

project. Up to this day, it retains its weird status of «obvious artistic

influence for game designers to be influenced by», except that no future game

designer has created anything like it; the world has moved on, and those

particular kinds of mushrooms that would let Alice shrink in size and pass

through Brian Moriarty’s half-open door have not been on the market in

decades. Who knows, though: perhaps in our current age of ever-diminishing

returns, when fresh ideas and approaches seem to be more scarce than the oil

at the bottom of a 100-year old Texan well, some modern day Indiana Jones

might eventually resume the search for those elusive fungi?.. |

||||