|

Mass Effect |

|

||||

|

Studio: |

BioWare |

||||

|

Designer(s): |

Casey

Hudson / Preston Watamaniuk |

||||

|

Part of series: |

Mass

Effect |

||||

|

Release: |

November 20, 2007 |

||||

|

Main credits: |

Lead writer: Drew Karpyshyn

Lead programmer: David Falkner Art director: Derek Watts |

||||

|

Useful links: |

Paragon

playthrough (22 hours 34 mins.) |

Renegade

playthrough (22 hours 46 mins.) |

|||

|

Basic Overview This review, written

during a tumultuous period in world history and, by extension, in my own

life, is dedicated to all the brave heroes of Ukrainian resistance in their

own war against the Reapers, and to all my good Russian friends, steadfast in

their struggle to resist their own brand of Reaper indoctrination from fascist

state media. Mass Effect is a pretty personal experience, so bear with me for a while as I lay down the I-me-mine groove on yʼall. Itʼll get better eventually, I promise.

Odd enough, I cannot properly recall what exactly prompted

me to return to the game — or at which particular point my initial

indifference turned to addiction, intoxication, and that particular kind of

feeling which drives players all around the world to write things like «I’ve

lived two lives — my fake, boring real one and my true existence in the Mass Effect universe». For a while, Mass Effect became the single

«druggiest» video game franchise for me since Quest For Glory in the early 1990s, and even today, I remain a

bit afraid of starting it up once more, lest everything else goes to hell

until I have completed the entire trilogy. (One of the reasons, actually, why

I still manage to hold out on the remastered Legendary Edition). And I know for sure that I am not alone in

this — the feeling of personal intimacy with the franchise is evident in a

lot of stuff people say about the games, and it goes way beyond collecting

action figures of Commander Shepard or celebrating International N7 Day with

your friends. Formal rituals are silly; true empathy with fictional art is

priceless. So what was it, specifically, that made Mass Effect so outstanding in a

veritable sea of RPG, adventure and action-based video game franchises? The

most natural benchmark for comparison here would probably be BioWare’s own

history. By 2007, the studio was already one of the leading giants in the

CRPG universe, having established its reputation with the Baldur’s Gate franchise, expanded and

defended it with critical successes such as Neverwinter Nights and Jade

Empire, and then carried it on a whole new level by taking over the

sci-fi genre with Knights Of The Old

Republic. As I wrote in my review of Baldur’s

Gate, easily the most important secret of BioWare’s success was their

ability to humanize the CRPG

experience — leave in all the combat fun and all the tricky stat business,

but add up the feeling that you are invested in the lives, actions, and

feelings of actual people, rather than simply playing a chess game of

strategy and tactics. Fans loved and got attached to the characters,

empathizing with them stronger than they would empathize with actual people —

letʼs face it, real

people, as a rule, tend to suck, and you can hardly ever count on them to

match your hopes and ideals, whereas a well-designed travel companion in a

RPG is precisely like that perfect

friend you could never afford in real life. For all their excellence, though, those early BioWare

games still had their limits, both technical and substantial. On the

technical front, the graphic design left a lot to be desired — the isometric

perspectives of Baldur’s Gate and Neverwinter Nights left way too much

for the imagination if you really wanted to fall in love with your

characters, and the still-too-crude 3D polygons of Jade Empire and KOTOR were

an insufficient, if important, step forward. In the substance department, the

games still suffered from a lack of realism — the dialog was largely

situation-based, centered around player quests rather than focused primarily

on immersing the player into a believable environment. If you so wanted, and

if you really put your mind to it, you could

make the Sword Coast into your second home. But it took effort. Yet the most important deficiency — even though some

hardcore RPG fans would rather call it an advantage — was the blank slate

state of your main playable character. Other than a few insignificant

biographic details, these guys never had much of an in-game personality,

offering you complete freedom to fill that one in with the aid of your own

imagination, subtly directed by the sets of choices made throughout the game.

Nobody at BioWare could be blamed for this: the designers were, after all,

just loyally following the classic RPG formula, in which having a blank-slate

protagonist, built by the player from the ground up, was one of the essential

ingredients, separating it from the «adventure» genre in which the name,

physical appearance, and biography of your character were set in stone from

the start. Mass Effect was the first BioWare game to dispense

with that — not as radically, perhaps, as CD Projekt RED’s The Witcher from the same year, in

which pre-game customization of your playable character was eliminated

completely (Geralt is Geralt, right?), but radically enough to create an

entirely new type of RPG experience. Your character had a preset name

(Shepard), a preset military rank (Commander), several finite and quite

concrete variations on his or her backstory, and, most importantly, a

well-defined sense of purpose. Choices still mattered, and Shepard’s

personality could be cosmetically shaped by the player in different ways, but

ultimately Mass Effect was a

specific story, set around a specific character. Freedom of player’s vision

was significantly sacrificed in favor of player’s empathy and involvement — a

tactic that must have turned off quite a few of those hardcore RPG fans, but

bought BioWare millions of new admirers, including those that would not

previously touch an RPG with a 10-foot steel pole (damage 1d8 +3 crushing,

THAC0 -2 bonus). Yet if the player’s vision was somewhat limited by the

game’s design, the designers’ vision was anything but. Mass Effect was BioWare’s first — and best — out of two major

franchises (the second one being Dragon

Age) built upon a completely original foundation, rather than a «rented»

one like the Forgotten Realms for Baldur’s

Gate or Star Wars for Knights Of

The Old Republic. Two persons deserve our primary gratitude for this:

project director Casey Hudson, who thought that creating a sci-fi universe of

its own would be a proper development step for BioWare after the success of KOTOR — and Drew Karpyshyn, the main

artistic mind behind the creation of the Mass

Effect lore and the storyline of the first game in the series. By the

time of Mass Effect 2, Karpyshyn’s

role in the game would already be seriously diminished, and by the time of Mass Effect 3, he would no longer be

involved with the project at all — a factor which, as some would claim,

contributed to the deterioration of the writing — but the Mass Effect universe as a whole was

fathered by Drew, and so, naturally, Drew’s influential shadow and all the

threads that he set in motion would be reflected in each of the franchise’s

installments to come. This circumstance is actually more important than it

looks, since conventional gaming critical consensus for the past 10 years has

tended to separate the three parts of the trilogy with a narrative that looks

something like this: (a) the original Mass

Effect was where it all started and established all the major lore, but

now looks somewhat dated and underdeveloped; (b) Mass Effect 2 is where it’s really at, the best game in the

series and one of the best video games of all time; (c) Mass Effect 3 is an okay continuation to Mass Effect 2, but thoroughly ruined by its inept and offensive

ending. I understand the logic behind each of these opinions, yet strongly

disagree with every single one of them — and in my reviews of the trilogy,

will try, to the best of my limited ability, to show why. Most importantly, in my opinion, the Mass Effect trilogy is precisely what

it is — a trilogy, a single, logical, wholesome, and well-rounded story told

in three installments, being the ideal video game equivalent of what The Lord Of The Rings is in the world

of literature and (the original) Star

Wars is in the world of cinema. If you, too, are a novice and want to ask

the question, «where should I begin with Mass

Effect?», the logical — in fact, the only adequate — answer is to begin

at the beginning; do not be a clueless noob by listening to brainless advice like

«well, the first game may be too rough about the edges for a modern gamer,

and all critics agree Mass Effect 2

is the best game in the series, so...». At the same time, just like each of the three parts of The Lord Of The Rings have their

stylistic and atmospheric differences, so would it be ridiculous to deny that

the same goes for Mass Effect. After

all, each game in the series was designed and produced by its own team in its

own time interval, with different sets of writers, programmers, and artists

who took into consideration both technological progress and fan feedback —

plus, even though Hudson and Karpyshyn had planned Mass Effect as a trilogy right from the start, it only takes a

single attentive playthrough of the three games to understand that there was

nothing like a wholesome, unified conception of what the story would be all

about when the original Mass Effect

went into actual development. (Rule #1 for any long-term project: always take care of the start and the end from the beginning, and

fill in the middle as you go — alas, only a miserable share of such projects

takes this rule into consideration). Seen from that perspective, the original game — Mass Effect — was, indeed, the most

«lore-oriented» of the series: one of its main purposes was to introduce, in

as much detail as possible, Karpyshyn’s vision of the Milky Way galaxy circa

2183 A.D., with all of its star systems, planets, races, technological

advances, and civilizational risks. Mass

Effect 2 would concentrate far more on the «buddy» aspect of the game,

being a bit more chamber-like in format and downplaying the grand scale of

the conflict in favor of personal melodrama. Finally, Mass Effect 3, with its Reaper invasion theme, would finish

things on an overwhelmingly epic scale (much like The Return Of The King), bringing in a completely different set

of emotions. Yet not one of the three parts is completely autonomous or

self-sufficient; not one of the three parts summarizes all the best about Mass Effect without flaunting some of

its worst; not one of the three parts can be fully and satisfyingly

appreciated outside of the context of the other two. Together, all their

deficiencies notwithstanding, they probably represent the single most

grandiose artistic achievement in the history of videogaming — not likely to

be topped in the near future of the medium, definitely not if it continues to

evolve along its current lines of evolution. |

|||||

|

Content evaluation |

|||||

|

Plotline

To

be quite honest, I am still not entirely sure if the Mass Effect saga could be completely excused and exonerated from

succumbing to the same temptation. Many things about its central plotline —

the fight against the giant, omnipotent, mysteriously Lovecraftian Reapers in

their crusade to eliminate organic civilization — did not make sense back in

2007 and made even less sense upon the completion of the Trilogy. But some ideas

work better when simply felt up your spine rather than when subjected to cold

intellectual analysis; and with Mass

Effect, BioWare’s designers showed a level of unprecedented ambition that

deserves unequivocal respect even if you still reserve the right to ridicule

Karpyshin & Co.’s concepts. One

such type of daring plot decision is giving you, the player, essentially no

time to familiarize yourself with this brand new world of 2183 A.D. before it

already finds itself on the eve of

destruction. The game seemingly begins slow and humble — as Commander Shepard

of the Systems Alliance (a.k.a. ʽEarthʼ, really), you have been directed to

proceed to the remote colony planet of Eden Prime in order to retrieve and

protect a recently excavated artefact, apparently left behind by the elder

race of the Protheans, whose nature and purpose are to be ascertained by

scientists. Even before you set foot on the planet, things begin to fall

apart when the Eden Prime colonists and soldiers are attacked by a mysterious

enemy — the robotic Geth, who are themselves guided by an even more

terrifying and baffling opponent that looks like a giant squid-shaped spaceship.

One of the very first things that the plot does is send you straight-on into

raging combat, and it is only after you have been properly baptized by fire

that you actually get a chance to look around and thoroughly immerse yourself

in the game’s universe. For me on my first playthrough, this was a turn-off,

what with my liking to take things slow at first and all; later, however, I

learned to enjoy the game’s prologue as an artistic decision rather than

simply a clever excuse for an early combat tutorial. As

a video game rather than a movie franchise, Mass Effect can afford itself the luxury of not being completely

anthropo-centric. The Milky Way Galaxy circa 2183 A.D. is supervised by a

Council run by three races, none of which is human — the «philosopher» race of

the formally gender-less (yet still strikingly feminine) Asari; the

«military» race of the Turians, each of whom looks like a cross between a

praying mantis and a Roman centurion; and the «nerdy» race of the Salarians,

nicely evolved lizards with a Thomas Edison fetish. The main residing

location of the Council is the Citadel, an interplanetary marvel of

technology that was originally discovered by the Asari — who somehow decided

to turn it into the galaxy’s central hub of operations even despite not completely

understanding how the whole thing works (somewhat similar to a tribe of apes

deciding to establish lodgings at an abandoned nuclear power station, but

whatever). The Citadel eventually becomes a harbor for all races — including

humans, the last species to discover the wonder of interstellar travel, but

also one of the most impatient to grab a proper seat on the Council and

impose their nasty Western capitalist-colonialist ways on the peacefully

grazing (not really) alien civilizations. Somewhere

at this point, Mass Effect still can’t

help falling back upon anthropocentrism, and, frankly, I do not blame it.

Although Commander Shepard may be customized as male or female, have

different backgrounds, class specializations, hair colors, and neck shapes, one

thing s/he may not be is not human

(in stark contrast, mind you, to most of BioWare’s previous franchises where

you could freely pick the race / species for your character). This is a

plot-required limitation: Mass Effect

is, first and foremost, a game about humans and the kind of change they bring

to whatever balance of forces they encounter upon their arrival. When, later

on, it becomes apparent that the giant squid-like spaceship first seen on

Eden Prime is Sovereign, the avantgarde sentry of the Reapers who appear on

the world stage every 50 thousand years or so to wipe out all advanced

organic civilizations... well, one might very well ask oneself the question

of just how coincidental it is that

this particular 50-thousand year cycle came to an end right at the very

moment that humans — and no other

race in particular — have appeared as an active force among the Milky Way’s

many cultures. Clearly, humans are special — and Commander Shepard is the

most special human of them all, the only one with whom Sovereign actually

condescends to have a brief conversation. Given

the rising tide of political correctness in the 21st century, one will regard

this message as either astonishingly retrograde and bigoted, or surprisingly

defiant and independent. I tend to gravitate toward the latter option — not

because the creators of Mass Effect

dared to promote colonialism, but rather because the entire agenda of Mass Effect is about posing questions

without giving unambiguous answers. In what might be one of the greatest

video game innovations of all time, the game utilizes the classic RPG

choice-based mechanics for much more than simply shaping the biography and

psychology of your playable character: it lets you shape the «moral course of

history» without explicitly praising you as a cosmopolitan hero or condemning

you as a nationalist villain. In Baldur’s

Gate, for instance, you nearly always had a choice between heroic and

villainous resolution of presented issues — save ’em all just because good

boys go to Heaven, or kill ’em all just for the mwahaha fun of it. But the famed morality system of Mass Effect is something completely

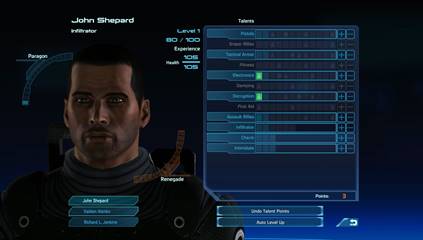

different altogether. From

the very start of the game, you can begin to shape your Shepard along the

«Paragon» path — marked in blue — or the «Renegade» path — marked in red; you

can also try out a mixed approach, but the game will try to penalize you for

that (some of the Paragon options are only open to you if you already have

enough Paragon points through choosing earlier Paragon options, and the same

symmetrically goes for Renegade). Many players, out of the naïve

goodness of their hearts or due to the old Dungeons & Dragons influence,

mistakenly think that «Paragon» equals «Good» and «Renegade» equals «Evil», which

is really only right if you consistently apply the exact same dichotomy to

Democrats and Republicans. More precisely, the «Paragon» path is the Henry

Fonda way of doing things, whereas the «Renegade» path is the Clint Eastwood

one (the ends justify the means, don’t be afraid to go all gung-ho when

circumstances demand it, the works), and the game rarely, if ever, castigates

you for choosing one over the other... at least, not directly: indirectly, going consistently

Renegade predictably results in a higher body count, which automatically

excludes you from certain interactions or further choices due to the

character becoming unavailable. In

the ultra-grand scheme of things — the war against the Reapers, which, in the

first game, takes on the shape of defeating Sovereign and his chief minion,

the rogue Turian agent Saren — going Paragon or Renegade does not make that

much of a difference; but it does matter a lot in your pursuit of the game’s

many secondary quests, such as meddling in the conflict between the nomadic

Quarians and their synthetic creations, the Geth, or in the fate of the

Krogans, a race of barbaric warriors condemned to «genophage» (artificial

sterilization) for the safety of the galaxy. Pretty much every small side

mission in the game has a Paragon or Renegade solution, and, much to the

honor of BioWare’s writer team, the game never pretends to judge you for your

actions — you, the player, always remain as the ultimate judge for all of

them. Most of the choices you can make have reasonable motivation, and many

will have you deliberating for quite a while before settling on one specific

part of the click wheel. (My own simple way of escaping the pains of doubt

was to play out a complete Paragon path and a complete Renegade path — but

admittedly, this is not nearly as fun as completely identifying yourself with

Shepard and making all the decisions precisely the same way you would make

them in real life). One thing about Mass

Effect is clear: while most of the questions it asks of you are

relatively simple, choosing the «right» answer is anything but. A

good example of BioWare’s subtlety in designing choice-based mini-scenarios

comes early on in the game during Shepard’s (optional) exploration of the

Citadel, when s/he comes across a pregnant woman and her brother having a heated

discussion on what is to be done with her unborn child. Apparently, her

husband was killed in action, and the baby, according to genetic scans, has

inherited from him a serious genetic defect that could lead to an early

demise. With the technological advances of the 22nd century, it is possible

to cure that defect while the baby is still in the womb, but with a small,

almost negligible, yet non-zero risk of severe consequences for the organism.

The brother urges the woman to take the treatment; the woman, naturally,

resists. It is up to Shepard to make his judgement and offer a «Paragon»

solution — the mother is always right — or a «Renegade» one — cold logic

should be obeyed. Obviously, if we act in accordance with the dominant moral

code of today, we should opt for the «Paragon» solution; yet the «Renegade»

answer is worded just as reasonably ("your husband’s death was not your

fault; but if you refuse the therapy, your child’s death could be") —

and hey, in the age of Covid and anti-vaxxer frenzy it actually takes on a

whole new level of convincing force. And

therein lies the magic of the story of Mass

Effect. Typical of video games, its plot twists and substantial themes

are not at all new — in fact, much has been written about how freely the saga

borrows from sci-fi and fantasy classics all over the place, starting with

the obvious nod to 2001: A Space

Odyssey (the mysterious Prothean beacons that evoke the alien monoliths

of the Firstborn) and ending with Battlestar

Galactica, much of the aesthetics and conceptuality of which was

appropriated for Mass Effect

without any scruples. What is new

is Mass Effect’s ultra-heavy

reliance on choice and non-linear storytelling — one reason why there is no

way it could ever be properly transferred to the medium of a movie or TV show

(unless they invite David Lynch to turn it into a wormhole-like extravaganza

filled with doppelgängers and shit). Of

course, the choice mechanics does not advance nearly far enough to truly make

your head spin. Shepard is never really given the option of turning to the

dark side (no matter what all those who hate taking the «Renegade» path might

say). Intermediate villains like the Thorian and Matriarch Benezia have to

die no matter which path you choose. All of your companions on board the

Normandy will always stay by your side regardless of whether you treat them

like pals or like dirt. Even so, the amount of branching options introduced

in the game was staggering by the standards of 2007 — especially when players

realized how important choices made early in the game could be for events

that would take place much later. Perhaps more than any other game released

before or since, Mass Effect gave

you the ultimate illusion of truly being able to bend the fabric of the

universe to your will, of creating your own timeline and imposing your own

values and strategies upon mankind. When

thinking about this from a cold analytic perspective, you do realize, quickly

enough, that it was only an illusion. On an objective scale, any classic RPG

game with random event generation — e.g. early Elder Scrolls titles — offers the player much more freedom, since

any runthrough of such a game will be uniquely different from the rest. For

all the variety of choice in Mass

Effect, the overall number of potential scenarios to be played out is

still finite, and each possible issue, want it or not, has been pre-planned

and pre-programmed for you by the game designers: those guys saw everything there is to be seen (apart from

glitches and bugs, of course) before you did. But herein lies the big dilemma.

Would you rather have to choose between such unique, unrepeatable,

specially-tailored-for-you quests as «the Duke of the province of Shabdallum

has asked you to save his daughter from the vicious goblins of the caves of

Boogagah in exchange for the magic Sword of Destiny?» and «the Lord-Mayor of

the city of Turiel has offered you to save a diplomat from the ice giants of

the mountains of Hullabaloo in exchange for the Amulet of Truth?» — or would

you rather prefer to deliberate as to whether you should or should not

exterminate the last representative of an archaic, intelligent, uniquely

endowed, but mortally dangerous species in a morally significant choice, but

one that is non-uniquely shared between you and millions of other players? In

some sense, this is similar to asking if one would prefer a huge,

mind-boggling, widely spaced open world setting, only to find that most of

this huge open world is empty space — randomly generated and verbally

repetitive NPCs walking around miriads of houses with locked doors — or a

smaller, more compact setting which offers far less space to roam, yet each

pixel of that space is worth exploring. Which brings us to yet another

important «anti-RPG» feature of Mass

Effect: although formally the game does belong to the class of «open

world games» (after Shepard becomes Spectre and captain of the Normandy, the

entire galaxy is free for him to explore), it still psychologically railroads

you into a more or less linear plot. The side quests of the game, even if

sometimes they do present you with interesting moral choices, are little more

than temporary distractions and diversions, offering you a quick break from

the main series of events — to catch your breath and level up. It is possible

to ignore them entirely and still have a complete and satisfying playthrough,

as opposed to, say, Baldur’s Gate,

where most of the actual fun was tied to simply roaming the environment and

picking up whatever mini-quest you could find. The

main plot of Mass Effect is not completely

set in stone: your three major missions (rescue the Asari scientist Liara in

the lava-ensconced ruins of Therum; defeat the mind-controlling Thorian and

rescue — or not rescue — the colonists on Feros; face Saren’s aide, Matriarch

Benesia, and rectify the consequences of a catastrophic biological experiment

on Noveria) may be pulled off in any order, and a belated fourth one (destroy

Saren’s laboratory on Virmire and face Sovereign himself in an intimate

face-to-face chat) can be started up right after any two out of three have

been completed. But these are essentially four semi-autonomous events of a

single plot, and moving them around each other makes about as much difference

as moving around any several out of Hercules’ twelve labors. There are funny,

albeit insignificant, consequences for those who, contrary to laws of common

sense, would want to hold out rescuing Liara until the very end — other than

that, your choices mostly matter within

each separate chapter of your adventure rather than in between them, and

that’s OK. The

plot as such is only mildly creative; this is not where the real strength of Mass Effect lies. A huge plant-like

monster busy mind-controlling and «vegetating» its victims; the last remnants

of an aggressive, super-intelligent species which stupid people try to turn

into biological weapons; a special agent gone rogue and allying himself with

the Dark Side «for the greater good of the Galaxy» — these are all

well-explored sci-fi / fantasy tropes, and I don’t think Karpyshyn or any

other Mass Effect writer could ever

pretend to introduce new philosophical ideas or unpredictable plot twists

into these genres. The good thing is that most of these plotlines are

generally believable, and, apart from an occasional cringe-inducing line of

bullshit pathos, generally well-phrased in dialog terms. One

scene in particular — Shepard’s defiant exchange with Sovereign during

their short face-to-face (or, rather, face-to-hologram) meeting on Virmire —

has acquired near-legendary status in the gaming community, though not

everybody can properly explain what it is precisely that makes the scene so

outstanding in a legion of "big-hero-taunts-big-baddie" moments in

various artistic media. Karpyshyn’s ambitious idea was to literally devise

the biggest-threat-of-’em-all — not just one of those boring megalomaniacs

with evil-empire-building goals, but a mystical force that challenges Life

itself for reasons well beyond Life’s limited comprehension. As charismatic

as Evil can be in books, movies, or games, its face-to-face confrontation

with Good is normally supposed to leave Good with at least some sort of moral

victory; in his/her exchange with Sovereign, however, Shepard’s moral victory

is impossible simply because his system of moral values is incompatible with

his enemy’s, whatever that system might even be. All the hero can do is

weakly generate truisms like "You’re

not even alive. Not really. You’re just a machine. And machines can be broken!"

and get deservedly roasted in response: "Your words are as empty as your future. I am the vanguard of your

destruction. This exchange is over." Although

the Reaper menace as such, especially visually, was clearly influenced by the

likes of Cthulhu, the most significant part of it was the enigma — the

inability to comprehend who the Reapers are, why they are doing what they are

doing, and if there are any possible means at all to thwart the threat they

represent. The next two games in the series would attempt to somewhat

de-mystify that enigma (we shall eventually try and decide just how

detrimental that decision was), but the original Mass Effect plays around it pretty well, though, come to think of

it, the ending, in which the way of taking down Sovereign turns out to be

fairly conventional after all, is a bit disappointing. You could, in fact,

argue that the ending is precisely where Hollywood takes over innovative

artistic vision — the kind of compromise that mars quite a few other BioWare

games — but you do not really play Mass

Effect in order to get to its ending; on the contrary, if you are a true Mass Effect player, you shall want to

put the ending off for as long as possible. There

are, after all, all those other

assignments to do, in addition to the major parts of the mission, during

which you get to explore various parts of the galaxy, stock up on your lore,

level up your character, and dabble in a lot of small, but challenging moral

choices. Put down or convince to surrender a crazy, murderous ex-military man

turned cult leader? Negotiate with or eliminate a renegade warlord

threatening the economic welfare of the Alliance? Save the hostages during a

major terrorist attack on a remote asteroid, letting the terrorists escape,

or wipe ’em all out while sacrificing the lives of the hostages (the plot

line of the excellent, if short, Bring

Down The Sky expansion pack)? You do see a pattern emerging here — soft

and peaceful solutions for Paragon, gung-ho bloodshed for Renegade — but the

missions feature plenty of small, but colorful characters with their own

mini-personalities to make up for the rather uniform arrangement of options.

Some of the assignments are more straightforward — roll in, shoot ’em up,

collect the loot, get out of there — yet on the whole, the small side

missions in Mass Effect are more in

line with similar missions in earlier BioWare games than any such missions in

Mass Effect 2 and 3 (that is, if you count the

«personal» missions related to your team members in Mass Effect 2 as parts of the main plot rather than auxiliary

side assignments). As

always in a BioWare game, Shepard can always set aside some time to pursue a

romantic option — even if the game offers surprisingly little choice,

avoiding same-sex liaisons (this would naturally be corrected in the

following games, as time went by and mores became more progressive) and

essentially just making you choose between an alliance with a member of your

own species or a «sexless», but still fairly hot Asari. Romance in the first Mass Effect game is handled with a bit

more intelligence and subtlety than it is in Mass Effect 2 (where the whole thing was seriously sabotaged by

too much fan service), but on the whole, romance in the game is fairly

independent from the plot as such and has more to do with the general idea of

bonding with your teammates, so we should probably come back to it in the

«Atmosphere» section. All

in all, while the plot of Mass Effect

in general is hardly its strongest point, it is solid to the point of me being

able to take it seriously. As I already mentioned, the first game — for

better or worse — has more to do with world-building than philosophy, but

there is enough story here to keep you intrigued and occupied, with great

attention to detail and rationality, even if, as befits an RPG, things are

incredulously romanticized at all times, and Commander Shepard quickly

becomes a figure more comparable to some legendary Indian warlord with

supernatural powers from the Mahabharata

rather than an actual military commander from some foreseeable period in

humanity’s future. (Still ten times more believable than any action hero in

any given Japanese RPG, though). |

|||||

|

Action

The

combat itself is not too complicated, though. Gone for good are BioWare’s

early-day AD&D mechanics, when opponents could hack at each other for

hours while waiting for a lucky roll that would never come. Luck has

virtually no place in Mass Effect;

all it takes is a bit of strategic thinking and taking care not to engage in combat

with enemies ten times as powerful as you, and you are largely in the clear

even on high-difficulty levels. Speaking of overpowered, because Mass Effect is — at least formally —

an open-world game, the majority of the enemies that you will encounter at

the end of your run will be more or less the same that you encounter at the

beginning. Synthetic Geth that come in simple and advanced varieties; berserk

half-ursine, half-reptiloid Krogan warriors; biotics-wielding, fast-moving

Asari warriors; generic human mercenaries — all of them you shall encounter

early on, and all of them will get progressively easier to overcome as you

level up, until, by the end of the game, you just toss ’em all aside like the

ragdolls they are. In other words, this is a classic example of the «generic

RPG difficulty curve»: tough as hell at the beginning while you’re wimpy,

easy as heck at the end when you’re Superman. Combat

mechanics of the first game has often been criticized for not being as

well-developed as in the other two, but while I do agree that some things

could have technically been designed better (worst of all is the decision to

have Shepard take cover automatically whenever s/he is in the vicinity of

cover — this means that you often find yourself glued to the nearest wall

when all you wanted to do is charge ahead), there are a few things in it that

make it uniquely and experimentally non-generic when compared to all

predictable shooter patterns (amusingly, the exact same thing is observed for

the first part of The Witcher

trilogy, Mass Effect’s equal in the

fantasy world, which also came out in 2007). The

most unusual thing is that Mass Effect

is an ammo-less shooter: according to the lore of the universe, each gun in

the game shoots not with bullets, but with tiny chips of metal accelerated to

supersonic velocity by decreasing its mass in a mass effect field. This means

that you always have a limitless supply of ammo, no matter what you shoot, but this comes at the expense of heat

buildup — so every once in a while you have to slow down your firing process

so as not to let your gun overheat (if it does, you’ll have to wait a long time for it to cool down, or

switch to a different weapon). This creates a quirky, possibly unprecedented

combat mechanic which conservative players, for some reason, totally failed

to appreciate — leading to the designers having to return to more traditional

ammo-based mode of combat for the next two games (with a clumsy and

unconvincing «explanation» added to the lore). Squad-based

combat functions pretty much as it does in any other BioWare game — you can

give yourself and your teammates orders in real time if you wish, but it is

more convenient to pause the game and bring up the command HUD, which gives

you the option to change weapons and exercise your special powers on the

enemy in peace and quiet while the action is frozen in place. (The PC version

makes real-time combat a bit more palatable since you can map a lot of your

own — but not your teammates’ — special powers onto keyboard shortcuts, which

is great by me since I think freezing the game with the command HUD during

combat really breaks up psychological immersion). That said, my personal

impressions are that your teammates, two of whom you can select for each

mission from a maximum pool of six, are there usually more for a show of

support than anything else — at least, when it comes to shooting in the early

parts of the game. Some of them have highly useful special powers which you

can exploit at will, but on their own, they are just as prone to distracting

you as they are to assisting you. As they level up along with you, they

progressively become more useful, but on the whole team-based AI would

certainly be much improved in the subsequent two parts of the trilogy. Speaking

of special powers, Mass Effect

introduces quite an ingenious system of classes for characters: projecting

the classic Fighter / Wizard / Thief trichotomy onto the science fiction

genre, they give you a choice of following the Soldier / Biotic / Tech Guy

path, with each of your companions having a fixed specialization from the

outset. The Soldier is essentially the equivalent of the Fighter — with lots

of blunt force and the ability to specialize in all weapons and wear heavy

armor, a brute (and somewhat boring) tank. The Biotic is Mass Effect’s version of the Wizard: if Shepard’s backstory

involves being irradiated by the mysterious «Element Zero» in the hero’s

childhood, you get awesome supernatural powers where you can shield yourself,

throw your opponents around, lift them in the air, or lock them helpless

inside a «singularity field» by harnessing the forces of the universe. The

Tech Guy (Engineer) is the weakest of the lot (few people like to play that

class, in all honesty), but at least he’s got a major advantage over all of

his/her synthetic enemies, whom he can hack, sabotage, or short-circuit in a

jiffy after a bit of practice. Then there are the mixed classes — my favorite

is the Vanguard, the game’s equivalent of the Battlemage, part Soldier, part

Biotic, an unstoppable killing machine who, when properly levelled up, can

throw around an entire enemy host and machine-gun them while they’re floating

around, completely helpless. Better

still, in stark contrast with today’s «advanced» shooters, giving you a

miriad of options, parameters, angles, displays, stats, and visual

pyrotechnics, Mass Effect keeps it fairly

simple. Winning a battle does require some work from the player, particularly

if you are playing on a challenging level, but combat never feels particularly

technical — having mastered the simple basics, you can just let yourself go

with the flow, instead of having to keep track of five million different

modifiers and statistics floating around the screen. (On lower difficulty

levels, you can actually relax and have your companions do most of the dirty

work for you — although, as I already said, on higher levels they become more

of a liability than a relief). Yet even if, on the whole, your combat

strategies are fairly limited, combining your talents with those of your

companions is a bit of an art; just like in BioWare’s earlier games,

defeating a powerful opponent usually takes a well-thought out plan of

action, rather than brute force and unlimited firepower. Classic

RPG elements that still managed to survive into the game include leveling up

by means of gathering XP, increasing your attributes as you level up, and

looting weaponry and tech upgrades from storage units or your enemies’ bodies

as you go. Interestingly, the amount of XP one can harvest in the game is

limited, since enemies defeated on various planets do not respawn and the

number of XP-yielding quests is quite finite; this pretty much eliminates the

very idea of «grinding» from the game, although maximizing your spoils still

requires quite a bit of tedious work (such as collecting all the minerals on

each planet you visit). Looting is also fun until a certain point, since in

the big scheme of things most of your common-grade weaponry is

interchangeable, and once you have completed the hunt for advanced-grade

equipment (which begins to pop up after you have achieved a high enough

level), your inventory will be clogged with endless tons of junk

(fortunately, all of it can be recycled into «omnigel», a useful substance

that helps you repair your equipment). Not all of this is perfectly well

balanced, but the overall system is, I would say, an intelligent compromise

between the strategic complexity of classic RPGs and the simplistic

straightforwardness of classic shooters. Other

than «clunky combat» (pish-posh), most of the gameplay criticism used to be

addressed at navigation across the various planets of the galaxy, most of

which, if you really want it and have plenty of time, can be done on foot,

but is usually supposed to take place in the M35 Mako, a six-wheeled

supertank thing which, in addition to giving you massive firepower, can move

through all sorts of rugged terrain — everything but water, in fact. The main

problem with it was the frustrating control system, which constantly used to

wrestle control out of the player’s hands, sending the Mako into series of

paroxysmal spins whenever you tried to brave a mountain peak (which was

fairly often, since a huge percentage of the landscape in the game is

occupied by dizzying mountain ranges). But while it might be true that this

aspect of the game suffered from a little less playtesting than there should

have been, the common answer to the problem was obvious — don’t use the Mako to brave mountain

peaks, try to circumvent them whenever possible. Sometimes the road takes a

little longer that way, but you probably do not traverse the Himalayas right

across the peak of Mount Everest, either. Just do not get it into your head

that the Mako can do everything (it

cannot scale a completely smooth wall of rock, for instance), and you’ll be

fine. (I also like the idea of penalizing the player’s XP while fighting in

the Mako — to get maximum reward, you always have to deliver at least the

final kill shot while on foot, which greatly adds to the challenge). As for the overall pace of the game, this is something you are completely free to set for yourself. Even if Commander Shepard seemingly has to hurry up in order to uncover and neutralize Saren and Sovereign’s evil plan, in practice you have no limits whatsoever, and can happily waste away as much time as you want on completing various side missions, hanging out on the Citadel, or just driving your Mako around randomly chosen planets, taking in the sights and sounds. Plot-wise, this does not make much sense, but no genuine RPG can survive without its sandbox aspects, even if, as I already said, Mass Effect does its best to reduce and compress them (and subsequent games would go even further). The quests themselves are fairly simple, featuring almost no «puzzles» as such — other than somewhat annoying mini-games of «decryption» where, in order to bypass locks and stuff, you have to guide your cursor through a series of spinning wheels to reach the center (ah, if only decryption were that easy in real life...) — but they do provide precious XP for leveling up, as well as teach you valuable combat strategy which you can then efficiently apply in the main quest, so skipping them is by no means recommendable, even if you do sometimes get to wonder what the hell you are doing here, shooting down packs of mercenaries or clearing out random dens of husks, when you are really supposed to be chasing down the bad guys who want to destroy the Universe as a whole. Oh, well. Less wondering, more shooting... |

|||||

|

Atmosphere

Mass Effect’s remedy to the challenge was simple

and efficient — if the building blocks of your universe are in danger of

feeling silly or annoying to the player, make it so that the player does not

even begin to concentrate on them. Instead, get the players involved, as

quickly as possible, inside the plot and the general tension; make the players

feel, as quickly as possible, as if the fate of the entire Milky Way really depended on their success. This

plan is put into action already at the very start of the game, when, through

the eyes of Commander Shepard, you are introduced to the wonder of the Mass

Relay — at this point in our future history, it is really little other than a

regular fast transit hub from one point in the Galaxy to another, but the way

it is presented, in a cut scene with as much atmospheric build-up as in a

regular Hollywood sci-fi blockbuster, makes you feel like a witness to

something truly phenomenal. Better still, at this moment you are Commander Shepard, making your way to the cockpit of the

SSV Normandy, so there is an immediately established equivalency between you

and your character (something that CD Projekt Red, for instance, did not get

quite right with the first Witcher

game from the same year). This

does not mean that Mass Effect has

no «atmosphere» outside of the interaction sphere of its characters. Quite on

the contrary, the combinations of visuals, cinematics, music tracks, and

sound effects chosen for each single location are nearly always impressive —

on the whole, more impressive, it could be argued, than in either of the

following games, because one of the chief goals of the first game in the

trilogy is to immerse you in Drew and Casey’s vision of our future. This

means great attention to detail in their world-building (there is, for

instance, a ton of printed lore for each of the planets in each of the star

systems you visit, including those on which the game does not even allow you

to land), even if you only really get to see a tiny fraction of that world up

close. Yes, most of the planets on which you and your Mako are allowed to

land will be lonesome and barren, with no cities, next to no infrastructure

and only occasional landmarks to draw your attention — but even so, rolling

through that landscape, with the camera gently panning around you, the music

setting a summer or winter mood, and the subtle lighting pushing you into

dawn-or-dusk territory, can be a beautiful experience; in fact, I have more

than once caught myself wondering about the potentially untapped wonders of

the real universe at large while letting myself be overwhelmed by the

artistic imagination of the BioWare guys. (And, for the record, this kind of

experience is only available in the

first Mass Effect game — 2 and 3 would be so much more story-oriented that Mother Nature would

largely sit them out). All

of the locations in which the main action takes place have distinct

atmospheric images of their own. Therum, the place of Liara’s imprisonment,

is a lava lover’s paradise: red, dry, dusty, and every bit as inhospitable

and unfriendly as it takes to get yourself out of there as quickly as possible.

The moribund colony of Feros, a curious mix of futuristic technology and

retro-futuristic archaeology, is drab, grey, dirty, and a great reminder of

humans’ irksome propensity to colonize even the shittiest spots on the map as

long as they stand to gain something. Noveria places that technology-drenched

infrastructure inside an immense, overwhelming ice palace — yet another

reminder of the same follies. And Virmire, the site of Saren’s dreadful

biological experiments, is a lush jungle where you can always step aside and

take the time to smell the roses before wiping out your next batch of Geth;

too bad you cannot ever revisit it in the aftermath of the battle (unlike

Noveria and Feros, where you can return any time you like until the beginning

of the final mission). Then,

of course, there is the Citadel, the central hub of the universe, where you

shall find yourself pretty often to pick up new missions, stock up on gear,

and learn the latest news. Programming and resource limitations have

unfortunately prevented it from looking as busy and lively as Karpyshyn would

probably have liked it to be — and unlike The

Witcher, whose NPCs all seem to have a dynamic life cycle of their own,

people in Mass Effect are, for the

most part, static, just standing or sitting in one place all through the

game; some of them are programmed to have a bit of dialog with each other

once or twice, then they just shut up once and for all. (On the other hand,

this at least saves them from all sorts of embarrassments resulting from poor

AI programming, like the infamous glitches of The Elder Scrolls: Oblivion). Even so, the vistas, the music, the

panoramic perspectives all make the Citadel — essentially a romanticized

version of the O’Neill

cylinder model — into a place where one can simply lose oneself for half

an hour or so, before coming back to reality and wishing you hadn’t. The

key word for most of these environments is ‘majestic’ — the panoramas, the

camera angles, the music, the sound effects, the perspectives all conspire to

make you feel a certain personal insignificance in light of the overall

overwhelming impression of the universe at large. A detailed tour of all the

available planets in the Mass Effect

galaxy would be a great bonus for those of us who enjoy reading up on popular

cosmology, astrophysics, and geochemistry and subsequently realizing that man

is not really the center of the universe, but, at best, a lucky random

spectator from the aisles. There is a quirky paradox hidden somewhere in

here, of course, since Commander Shepard is actually one of those men (or

women) who is endowed by Fate with some serious agency — but that agency

feels practically non-existent whenever you are driving your Mako across some

red-hot volcanic territory or through a heavy blizzard on an ice-covered

planet whose only inhabitant is an occasional Thresher Maw monster who likes

to have Makos for breakfast. Still,

as emotional and/or thought-provoking those vistas might be, Mass Effect’s major attraction lies in

the design of and interaction with its organic constituents, rather than its

natural and technological beauties. In general, Karpyshyn’s and Brennan’s

take on the magical 22nd century does not stray too far from the «epic-romantic»

take of most of our beloved sci-fi sagas — perhaps it is just a slight touch

more grounded in realism than Star Wars,

but in a world where most of the people dress up with a serious nod to

Renaissance nobility, interact with each other in exquisite literary language

(blame it on the automated translation services if you want), and make

advantage of the newly opened worlds by dashing through them in

swashbuckling, Wild West fashion (hello, Firefly

influence!), you will not be troubled by too many similarities with our own

pesky, mundane, boring-as-hell existence. Yet neither is the living world of Mass Effect just a collection of

recycled clichés and stereotypes — derivative as it is, there’s plenty

of imaginative power here to keep you surprised and intrigued. Most

of the races of Mass Effect do

behave in relatively strict accordance with their racial stereotypes. The

Asari move around and converse in gracious, elegant, eloquent manners,

holding up their roles as the wisest — and, subsequently, somewhat

condescending — overseers of the galaxy. The Romanesque Turians are

code-bound — stern, stuck-up, gruff, and just. The big and rowdy Krogans are

the proverbial burly dock workers from whom wimps like us prefer to stay away

(until, by some weird chance, you manage to get under some of their skins and

see them for the big babies they really are). Then there’s always the next

step in the advanced cogwheels of one’s imagination — races like the Hanar,

who look like jellyfish, talk like David Byrne on a Brian Eno-produced

record, and worship their deities (the ‘Enkindlers’) with all the verve of a fundamentalist

sect. Or like the Volus, who look like little badgers, wear protective suits

which distort their voices, and perform the classic sinister literary

function of «international Jewry» with their shady financial dealings. Or

like the Elcor, who, although they play a very small role in the overall

story of the saga, quickly managed to become one of the most beloved races of

them all due to their particular manner of conversing. Speaking

of the Elcor, I would just like to point out that they are perhaps the most

transparent example of how Mass Effect’s

world-building often (not always, but often enough) tries to ground cultural

particularities in scientific explanations — the Elcor, according to the

lore, have evolved in a very specific high-gravity environment, which has

conditioned their large bulk, sluggish behavior patterns, and minimal

physical activity. The Elcor speech, in particular, is presented as a dull,

toneless, monotone chain of sound whose emotional modulation is so subtle

that no other race can perceive it, which in turn requires the Elcor to

preface their every uttering with an adverbial note on its emotional nature

("genuine enthusiasm: I delight in

telling the history of my people"... "chastising rebuke: your tone is inappropriate", etc.).

Although this is just a flourish — the Elcor play no significant role in the

story whatsoever — it goes to show just how much thought, care, and humor was

invested in the designers’ vision of our future. It’s still magic vision

rather than realistic vision, of course, but the magic of Mass Effect is not cheap, fluffy

magic; even its most whimsical applications can still have a symbolic

significance. (And we might probably all gain something if we ever thought of

instituting a «talk like an Elcor» day or something). And

still that ain’t all — in fact, I have not even begun yet to talk about the truly major part of Mass Effect’s atmosphere. Roaming the

Milky Way may be a great source of melancholic excitement (or was that

exciting melancholy?), and interacting with all of its bizarrely-designed

creatures may be a great way to open up one’s creative and imaginative

boundaries, but above and beyond everything else, Mass Effect is a «buddy-oriented» game. The most important

characters around are the members of your multi-racial team, whom you will

gradually learn to like, protect, empathize with, and ultimately treat like a

part of your extended family — brothers, sisters, and (possibly) lovers. Although

BioWare had always focused on «team-oriented» RPGs, right from the very first

Baldur’s Gate game and onward,

arguably no other BioWare franchise placed as much importance on the players’

interaction with their party members. Unlike Baldur’s Gate, where you can choose up to five partners from a

huge pool of potential candidates, Mass

Effect gives you a strictly limited number of companions — two humans

(the biotic Lieutenant Kaidan Alenko and the gruff warrior lady Ashley

Williams), one Turian (the inimitable security officer Garrus Vakarian), one

Asari (the inquisitively intellectual Liara T’Soni), one Quarian (the

inquisitively tech-savvy Tali’Zorah nar Rayya), and one Krogan (Urdnot Wrex,

a big-hearted mercenary with equal passion for affection and destruction).

Although you can only choose two of these guys at a time to accompany you on

any of your missions — resulting in billions of hours spent by despairing

players trying to figure out the best candidates for the appropriate tasks — they

will still always be available in the hold of the Normandy for conversation,

and it is more likely than not that you will get to know each of them in

detail before the game is over. It

is not just that each of the companions is equipped with his or her

backstory, a full-fledged personality, and a significant role in the

unfolding of the main plotline. It is the extra care invested in their belonging to your personal sphere of

acceptance and responsibility that matters. Your chosen companions follow you

each step of the way, sometimes clumsily running into or skilfully avoiding

obstacles, sometimes randomly interacting with you or with each other,

sometimes making insightful or funny comments on whatever is going around —

and always ready to draw their guns at the smallest sight of trouble. They

issue warnings about approaching enemies, express genuine concern about your

welfare ("Shepard’s been hit!"

is usually the last thing I hear before I die), and are always ready to chat

you up whenever you feel like taking a break from the tension and excitement

of mission combat. When it comes to chatting, the writers for specific

characters took good care, in particular, to stay on a well-balanced fence

between strong, but not dumb and completely predictable, stereotypization, and

throwing in lots of personal nuances which, rather than diluting a

character’s individuality, end up somewhat sharpening it. Garrus Vakarian,

for instance, is introduced as a sort of alien Dirty Harry, his mind fully

bent on dispensing strict and stern justice by any means possible — yet he

also has a soft, shy, almost sentimental angle to him which instantaneously

makes the guy into a ladies’ favorite even despite his addiction to placing

well-targeted bullets in between his victims’ eyes. Wrex is a ruthless,

bloody mercenary who almost seems to enjoy blowing stuff up for the fun of it

rather than for the money, but he is also a tragic figure, doubly trapped by

the sorry fate of his entire sterilized nation and that of being one of its most intelligent — and, therefore,

one of its most unhappy — representatives. Tali, the Quarian, combines the

nerdy excitement of a tech-crazy young person with the deep resentment and

psychic trauma of an entire nation that had to pay a terrible price for its

oversights. And Liara, the Asari, is given the complex task of a young Sage

trying to psychologically fit in with a bunch of ignorant undergraduates

(amusingly, it is only when you decide to bed her that her high horse somewhat

naturally and inevitably melts away). With all those delicious aliens around, players

often tend to underestimate the value of Shepard’s human companions, Kaidan

and Ashley — an outcome that I prefer to ascribe to either the common exotic

ways of thinking ("aliens fun, humans bo-o-o-o-ring!") or liberal

guilt ("aliens all good, humans all bad!") rather than the writers’

fault, because both of these characters are fleshed out just as solidly as

their interplanetary buddies. Kaidan, introduced as a victim of the corporate

industry — he, like many others, had been intentionally exposed to Element

Zero in order to be trained as a biotic super-soldier — manages to overcome

all his traumas and act as the voice of reason and compromise throughout the

game; Ashley, on the other hand, comes across as more emotional, flippant,

and ruthless, not to mention religious (a big point is made of her believing

in God, though it is actually never specified which God) and xenophobic — traits that made her character fairly

allergic to a large number of players, with reactions of the "I hate

Ashley, she’s so racist" type being fairly common in the fan community.

This is, of course, uneducated bullshit: «racism» implies a belief in the

objective superiority of your own race over everybody else’s, whereas Ashley

Williams, from her military-family perspective, perceives the other races as

a potential threat to humans rather than a corrupted line of evolution — and

this makes her story arch particularly involving and instructive, as she

gradually warms up to her non-human companions and accepts that cooperation

should be preferred over conflict. One aspect of all this companionship which people

often overrate, I think, is your ability to influence, over the course of the

game, the personalities of your companions. For sure, there are a couple

strategies and decisions you can embrace that will directly influence their

fates — most notably, during the Virmire mission, where your personal history

with Wrex will determine his fate and where you also have to decide which of

your human companions is more suitable for a last heroic stand against

overwhelming odds. But fates are not personality trajectories, and there is

really very little you can do about those. You might, for instance, take a stand

with Garrus on his gung-ho mentality, or you might softly (or sternly) rebuke

him for being way more trigger-happy than necessary — but the farthest you

will get away with this is to hear a "I’m glad we’re on the same page

here, Commander" or a "Well, you’ve given me something to think

about, Commander" from his silky-soft vocal chords. Despite occasional

illusive moments like these, the characters’ personalities (unlike your own)

are, on the whole, set in stone; you may alter some of their actions, but their minds are largely set on a pre-fixed

path whose twists and turns are determined by the plot rather than your click

wheel. (Ironically, the only person whose mind you can actually influence and

change by the end of the game is your chief nemesis, Saren!). But in the long run, this does not really matter: in

fact, even if I am sure that this inability to change other people around you

was largely dictated by technical reasons (too much trouble incorporating the

consequences of too many significant choices), you could also argue that

Shepard’s companions are there not to serve as impressionable rag dolls, but

to surround the title character with strong, resilient personalities, against

which it is fun to try and employ different strategies of interaction (from

the Paragon’s respect and admiration to the Renegade’s irony and

condescension). No matter what you do here, the writers and programmers did a

great job of molding, over time, your potential «travel companions» into your

best friends — and it is no wonder that, above everything else, it is this aspect of the game which would

end up as the most improved and deepened in Mass Effect 2, ultimately becoming responsible for turning the

second part of the franchise into the most critically applauded one (a decision

which, as I already said, I can fully understand, even if I do not

necessarily subscribe to it). And thus it happens that, in the end, of all the

great sagas Mass Effect is probably

closer to The Lord Of The Rings than anything else — it is something like 40%

about the wonders and marvels of an imaginary alternate universe, and 60%

about the comfort and salvation one finds in genuine friendship. Oh, and, of

course, there is also that end-of-the-world moment on the horizon to be

considered; but just as it is with The

Fellowship Of The Ring, so does the first part of the Mass Effect trilogy mainly just hint at the inevitability of that

moment’s arrival. The warning signs are everywhere — in the form of the

horrifying dehumanized husks, the indoctrinated minds of the unfortunate

colonists on Feros, the disturbing conversations with Saren (= Saruman?) and

Sovereign (= Sauron?) on Virmire, and, of course, the climactic final battle

with Sovereign on the Citadel. But the climactic final battle still ends with

a Hollywood-style heroic victory, and the universe at large is still largely

oblivious of the mortal danger that awaits it, so even as you discover more

and more information about the genocidal cycle of the Reapers, your mind will

still be way too busy processing the visual and aural delights of the Milky

Way’s planetary bodies, and your soul will still be mainly devoted to

empathizing with your virtual human and non-human buddies. Some might, in fact, be disappointed with the

relative (I stress — relative) lack

of a strong sense of danger in the game. By the time you get to the final

battles on Ilos and the Citadel, for instance, you will probably be so

overpowered (provided you were diligent enough to complete as many side

quests as possible) that slicing through the thick enemy lines, most of which

will consist of creatures you have already fought multiple times anyway, will

be like slicing through exceedingly feeble layers of cake. (Even the last

boss fight, with a huskified Saren who has an annoying habit of overheating

all your weapons, always felt more tedious than exciting to me). But on the

whole, this hardly seems like a big problem because Mass Effect is not a

game about the end of the world; it

is a game about the beginning of a

world that, incidentally, somehow threatens to come to an end even before you

have fully finished exploring it. And that’s fine. It’s far more poignant,

anyway, to admire a chunk of beauty with the realisation that it is also your

duty to save it from extinction, than to simply admire it, period. Isn’t

it?.. |

|||||

|

Technical features |

|||||

|

Graphics The first thing one usually hears when discussing the visuals of

Mass Effect is the sound of heavy

sighing and the perennial cliché of «well, unfortunately, the graphics

of the first game have not held up as well as those of Mass Effect 2 and 3...»

— because, as you well know, 2010 is the year where civilization really took

off, while as early as 2007 we were still living in the Stone Age. On a

serious note, though, while the graphics

of Mass Effect may indeed have

still been technically inferior to the graphics of Mass Effect 2 (a problem well remedied by the numerous HD mods to

the original game, and in more recent times, by the texture upgrades of Mass Effect Legendary Edition), the art of the original Mass Effect was every bit on the

level, and in no way inferior to the artistic designs of its sequels.

That said, there is a sharp visual contrast in Mass Effect between «nature» and

«technocracy», and as far as the former is concerned, it is probably fair to

say that the team’s efforts in visualizing and animating the various planets

across the Milky Way were pretty much unprecedented for their time. The

landscapes that unfold before you as you traverse them in the Mako or on foot

are relatively minimalistic — but the lack of detail helps concentrate the

effort on making these landscapes realistic, and the transitions smooth as

butter. The rendering never looks too schematic or blocky; you know that the actual planets are

constructed from repeating constituents, because there’s no way any artist

would have drawn all those useless mountains, plains, and ravines, but you

never truly feel like it. Ride

across the lengthy perimeter of any of those planets, and while their overall

look will rarely change from one point to another, you will never get the

feeling of «oh, I’ve been in this exact spot two minutes ago» (unless you

messed up your compass and you really were

in this exact spot two minutes ago). Lest the landscapes, most of which fall under three similar

categories of «green», «snowy», and «sandy», eventually do begin to feel

repetitive to you, the artists took care to diversify them with various

tricks of lighting — depending on the specific physical and chemical

properties of the planets’ suns and atmospheres, the planets may be bathed in

various shapes of purple, violet, yellow, or amaranthine, and change color

depending on your position relative to the sun. There is no day-and-night

cycle (which probably made sense, since you are rarely supposed to spend too

much time in one place), but some of the planets are «day-time» and some are

«night-time» environments, which, combined with their «winter» vs. «summer»

properties, makes for a whole lot of various flavors. With all that

creativity, the lonesome colorful landscapes feel like living illustrations

to minimalist or ambient soundtracks — Brian Eno, Harold Budd, or Philip

Glass coming to mind — and every once in a while, you get really tempted to

forget all about the plot and just spend a little time rolling through those desolate,

solemn, serene landscapes, contemplating the mysteries of the universe. Things get entirely different when we get back to civilization —

not human civilization, of course, which seems to have adopted the Globalized

Galactic Standard by the time the events in Mass Effect are taking place, but the kind of civilization whose

styles and trends seem to be dictated by the Citadel, where, appropriately,

you are bound to encounter the latest and greatest in techno-fashion. Here,

Derek Watts, the art director of the game, is quick to acknowledge the

influence of Syd Mead, the famous visionary behind Blade Runner and lots of other stuff; Syd’s futuristic panoramas,

celebrating a bright,

glossy, cocoon-style existence for humanity in the future, at times do

seem almost borrowed, stroke-by-stroke, by Derek and his team to depict the

Citadel, as well as smaller, more specialized hubs such as the ice-bound

Noveria. Quite a few people, myself included, feel a bit uncomfortable with

this vision, in which nature has no place whatsoever, other than contributing

a few plastic imitations for nostalgic purposes; I do not really know if

Watts’ idea was to simply create a place of dazzling futuristic beauty or if

it was his plan all along to imbue it with a sense of discomfort and

underlying danger, but I’d say he fully succeeded with the latter, be it

intentionally or accidentally. For all its graphic beauty — the lakes and fountains on the

Presidium, the elegant trees with autumn-color leaves in the Council

Chambers, the lustful red lights of Chora’s Den — the Citadel is primarily

designed as a highly practical, ergonomic environment. Every single object is

polished and rounded, designed in the kind of minimalistic-industrial style

that is usually so revered among the intellectual parts of present day high

class (as opposed to the non-intellectual ones with their golden toilet bowls

and dazzling baroque grotesqueries on every corner). The same style,

curiously, is carried over to every single other planet — apparently, the

intergalactic IKEA delivers its furniture, as well as its wall panels and

automated doors, to all corners of the Milky Way, which would probably make

sense if at least the typical «rich man entourage» of the game was visually

different from the «poor man entourage», which it ain’t. This is most likely

a technical limitation, but the unfortunate effect is that pretty soon you

may be getting sick of the same style applied whenever you go. At least the

Prothean world of Ilos, where Shepard gets at the end of the game, is allowed

to have its own design — you don’t get to see a lot of it, but it does have

its own idiosyncratic, somewhat «Atlantis-style» outlook. In short, the Mass Effect

universe, from a purely visual perspective, is one I’d rather be glad to

visit than dwell in — too stuffy and claustrophobic when it comes to

civilization, too lonesome and desolate when it doesn’t. That’s OK, though;

it makes the idea of a Reaper invasion regularly cleansing the universe of

its organic-induced disentropy somewhat more palatable. I’d be sad and blue

if they were to destroy Notre-Dame de Paris, but the sterile, plastic beauty

of the Citadel does not move me nearly as much, so if this is the ultimate

fate of humanity, so be it. (Gunnery Chief Ashley Williams seems to share my

concerns: "they’ve built

themselves quite the lake...", she quips while traversing the huge

space of the Presidium, "wonder if

anyone’s ever drowned in it"). Where the game truly

excelled, however, was in its graphic representations of the characters.

Interestingly, for the first time ever in BioWare history Mass Effect included a genuine

character creation algorithm, allowing you to design your own Commander

Shepard from individual components, something that was supposedly impossible

to achieve with BioWare’s own older game engines such as Infinity and

Odyssey, but achievable with the licensing of Unreal Engine 3 (probably not

the only reason why BioWare, well-known for their original engines, this time

around decided to run somebody else’s software, but an important one). The

end result was not perfect — for some reason, while I was able to design

quite a few good-looking female Shepards, most of the male ones came out as

the result of way too much inbreeding, so in the end I always played the

default male character, based on Dutch model Mark Vanderloo. But what was perfect was the way the BioWare

team learned to animate their heroes. Be they pretty or ugly, the facial

dynamics, all the way from the twitching eyebrows to the playful mouth

movements, came out as extremely realistic — making Mass Effect one of the first 3D games, in effect, where it became

obvious that technology had finally triumphed, and that the 10-year journey

from the original Polygonal Nightmare to believable realism was finally

nearing its end. Generally speaking, the characters of Mass Effect, humans and aliens alike, look alive. Their mouths

seem to be articulating actual words (rather than just opening and closing),

their eyes reflect their emotional states, their gestures echo the intentions

of their messages. Even characters whose faces are permanently hidden behind

masks, like Tali or the Volus merchants, are able to convey extra psychological

detail through subtle twitching, shrugging, and fidgeting. While conversing,

characters sometimes move around, rather than become forever rooted to the

same spot; cut scenes feature plenty of cinematographic tricks, changing

scales and perspectives to produce an authentic movie effect. Of course, this

is nothing new in the 2020s, but the important thing is that it all still

looks good in the 2020s — even without all the graphic upscaling of the Legendary Edition, Mass Effect still produces a highly

realistic impression, and whoever would want to complain about the game «not

holding up» is well advised to load up Knights

Of The Old Republic and re-learn the true meaning of «not holding up» (note

that this is only a criticism of KOTOR’s