|

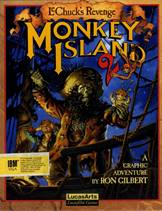

Monkey Island 2: LeChuck’s Revenge |

|

|||

|

Studio: |

LucasArts |

|||

|

Designer(s): |

Ron

Gilbert / Dave Grossman / Tim Schafer |

|||

|

Part of series: |

Monkey

Island |

|||

|

Release: |

December 1991 (original) / July 7, 2010 (remake) |

|||

|

Main credits: |

Graphic Art: Peter Chan, Steve Purcell, Sean Turner et al. Music: Michael Land, Peter McConnell,

Clint Bajakian |

|||

|

Useful links: |

Complete

playthrough (Special Edition only;

5 parts, 308 mins.) |

|||

|

Unlike Sierra On-Line,

LucasArts never got to properly fetishize the Art of the Sequel. Admittedly,

the studio released altogether fewer than twenty adventure games in its

lifetime, most of which were not big sellers and therefore not officially

encouraged to get a continuation; still, one can hardly argue that most of the time, the creative minds

at LucasArts knew well enough the golden rule — only produce a sequel when

that sequel has something new to say, rather than churn it out just because

the market is said to demand it. Monkey

Island 2 happened to

be one of those lucky exceptions: more or less the Empire Strikes Back to its predecessor’s New Hope. Ron Gilbert himself states that the idea and concept of

a sequel to Secret Of Monkey Island

was already playing out in his mind before the first game was completed, and

this looks very much like the truth, given how smoothly the second game

expands and deepens the themes of the first one. Upon first sight, it simply

might seem bigger: more puzzles, more characters, more locations, more

dialog, more everything — which is not that surprising, given the much larger

team of employees assigned to Gilbert, Grossman, and Schafer’s supervision

(so much larger, in fact, that they managed to churn out the final product in

merely one year). Upon second sight... upon second sight Monkey Island 2 is simply the most perfect Monkey Island-type entertainment you are ever going to get. Due to its bigger budget and to rapidly

changing times, Monkey Island 2

featured quite a bit of graphic, musical, and overall design innovations for

LucasArts — but the main thing about it is that it represents the crowning

achievement of Ron Gilbert during his short, but mega-important period of

work with the studio. By the time the game came out, Gilbert was no longer

the sole-reigning intellectual king at LucasArts: his newer partners, Dave

Grossman and Tim Schafer, were proving to be comparable visionaries (as they

would soon prove beyond all reasonable doubt with Day Of The Tentacle), and so were occasional walk-ons like Loom’s Brian Moriarty. It is possible

that he was beginning to feel jealous of the competition, or, more probable

perhaps, felt himself repressed by the changes in the studio, which was

rapidly growing from an originally small and family-like art department to a

big business enterprise. Yet lightning rarely strikes twice, and Ron never

managed to find once more the same acclaim he had received for his time with

LucasArts — so, for all we know, Monkey

Island 2 remains his comprehensive swan song, a final masterpiece of

design, humor, and imagination which also, incidentally, happens to be one of

the best lessons on how to produce meaningful sequels. I do admit that all these big, gushing

words may reflect a bit of personal bias: Monkey Island 2 was one of my first experiences with a LucasArts

game (possibly the second one I ever played back in the early 1990s, after Maniac Mansion). However, replaying

the remade version right after completing the remake of Secret has, in fact, done nothing but firmly convince me of how

lucky I was back then — and while I do enjoy watching the birth of Guybrush

Threepwood as much as the next guy, and certainly recommend playing the

dilogy in its proper order, I have not the slightest doubt about which part

is the hors-d’oeuvres and which one introduces the main course. (And, for the

record, I do stress the use of the word «dilogy»: all subsequent Monkey Island games, good or bad,

have to be regarded in quite a different light after the departure of their

chief originator.) |

||||

|

Content evaluation |

||||

|

For the largest part of the

game, the story that Gilbert came up with for the second part of Guybrush

Threepwood’s adventures is not much of an advance on the first part. In Secret Of Monkey Island, Guybrush

spent most of his time passing the various trials which would allow him to

join the proud ranks of piratehood; in Lechuck’s

Revenge, after a short prologue in which our hero has to chase away the

biggest bully on Scabb Island, he spends most of his time assembling the four

map pieces that will allegedly lead him to a pirate treasure — the infamous

«Big Whoop», Gilbert’s personal McGuffin which, in the end, turns out to be

the true key to the entire Monkey Island problem... but let us not run too

far ahead of schedule. The main purpose of the game remains

precisely the same — to poke fun at stereotypical conceptions about our

mythical past by clothing them in practices and attitudes which directly

relate to our annoying present. (Whoever tries to get all indignant about the

existence of gas stoves, laundry tickets, and Elvis medallions in the Golden

Age of Piracy clearly does not get the joke so much that he probably does not

exist). But the writers manage to come up with enough fresh ideas to never

make things seem like mere rehashing of the narrative of the first game. For sure, there are returning

characters who are already on the verge of becoming the series’ running gags

— none more so than the business-savvy Voodoo Lady and Stan the Salesman —

but there are also multiple new faces with new personalities, such as the

wimpy, self-pitying Wally the Cartographer; the strong-willed, quick-witted

Captain Kate Capsize (some of the funniest moments in the game happen

whenever Guybrush tries to interact with her using the Pick Up option); the cartoonishly food-obsessed Governor Phatt of

Phatt Island (too bad we never get to see him outside of his gastronomically

enhanced bed); and lots of other, smaller, but nearly always picturesque

characters to populate the Monkey Island universe with every possible

literary or cinematographic stereotype you ever met. Not all of these characters are dropped

on you at once, though. The game has an ideal structure where Act 1 confines

you to just one island, helping you familiarize yourself with the game

mechanics while focusing on one single task (do away with the bad guy); Act 2

puts you in Open World mode, letting you cruise back and forth between three

main islands in search of the map pieces; then the final acts trap you in the

bottleneck of the final locations (LeChuck’s Fortress and then Dinky Island)

for the most action-filled parts. It goes without saying that even if the

game is not that much longer, on

the whole, than Secret, it still feels much longer because the

pseudo-Caribbean space slowly begins to feel quite spacious — and each of the

spaces has its own character: the dirty and carefree pirate-controlled space

of Scabb Island, the posh and commercialized official space of Booty Island,

or the dangerous and totalitarian space of Phatt Island. Curiously, one of the central plotlines

of the original game — Guybrush’s «adorkable» romance with Governor Elaine

Marley — has been relegated to the sidelines: Elaine is now an entirely

episodic character, briefly involved in one of the subplots and acting as a

purely passive onlooker in another. Moreover, she even gives the impression

of being intentionally dumbed down (one of the easier puzzles involves

Guybrush having to re-woo his love by choosing suave and corny compliments

over insults and sarcasm), which sort of makes me wonder if Ron Gilbert

hadn’t been dumped by his girlfriend or something like that in between 1990

and 1992. That said, the quirky aspects of the Threepwood / Marley soap opera

have always seemed one of the game’s weakest assets to me anyway, so the less

romance in a Monkey Island game,

the better, I say. Some critics (like Jimmy Maher, the

eminently readable Digital

Antiquarian) have had complaints about the character of Guybrush

Threepwood evolving into a more mischievous and unpleasant personage, rather

than the comparably innocent and charismatic buffoon of the original game —

citing such examples as his stealing a monocle from a harmless and

defenseless cartographer, or locking up another innocent person in a coffin.

On purely objective grounds, this is a correct observation (there are indeed

fewer moments in Secret which

could be openly judged as «immoral»), yet somehow it never ever struck me

when playing both games back to back that Guybrush was undergoing some sort

of negative character transformation. Most of the NPCs in the Monkey Island series are caricatures,

similar to Grand Theft Auto and the

like, and this automatically means that they are all fair game when it comes

to using them for some grand purpose or other, as long as it does not lead to

irrepairable harm (after all, Guybrush does

return the monocle to Wally in the end, and as for Stan the Salesman, locking

that guy inside a coffin is probably the mildest punishment for all the

splitting headache he causes you, the player, over both games). Anyway, Guybrush

Threepwood was never intended to be a goody-two-shoes politically correct

character; complaining about his occasional misdemeanours makes about as much

sense as canceling the likes of Till Eulenspiegel or Tom Sawyer. The single most important thing that really separates the game from its predecessor

— or, rather provides it with a conclusive finale that inverts the meanings

of both — is the controversial ending, in which the feud between Guybrush and

his arch-enemy, the Ghost Pirate LeChuck, receives a totally unpredictable

and extra-dimensional explanation, one which, apparently, came to Gilbert

after a long, painful search in a momentuous flash of inspiration, yet found

relatively little support from the fans. Considering that the entire concept

of Monkey Island grew out of

Gilbert’s fascination with a Disney amusement park, I would conclude that

landing the game on a finish line of a Disney amusement park was a stroke of

genius rather than an arbitrary blunder, not to mention all the Freudian

undertones of the Guybrush / LeChuck family relationship (into which Gilbert

even managed to insert a deeply unsubtle Star

Wars reference — this was a

LucasArts production, anyway). But it did create a problem, essentially

cementing the status of Monkey Island

as a definitive dilogy, with hardly any hope for a sequel — obviously, not

too many people were happy about that, particularly since their appetites had

already been whetted with a two-game series. Worse, as inventive as the ending was,

it left too many threads just hanging in the air — since the storylines of

most of the characters turned out to be simply abandoned. Did Elaine manage

to escape from Dinky Island? Did Wally survive or perish in the explosion?

Would Stan the Salesman be left forever rotting in his coffin? If you thought

that the abrupt ending was a rather cheap cop-out from answering all these

questions, you would certainly be justified. It feels too abrupt, too rushed,

too jarring — very likely, the result of hurrying up to get the product

shipped in time for Christmas — and, honestly speaking, were I ever in charge

of remaking the entire franchise, I would rather have it restructured as a

trilogy, swapping around the endings of LeChuck’s

Revenge and The Curse Of Monkey

Island to create a more coherent and satisfying experience. As such, the

ending of the second game feels sprung on the player way too brutally, while

the beginning and main premise of the third game, no matter how much the

authors struggled with it, end up making no sense at all (but more on that in

due time, when we get to savoring the flaws of the 1997 sequel). Nevertheless, for all of its

shortcomings, the ending of Monkey

Island 2 still has to be commended as one of the most daring artistic

moves in video game history up to that point. The older scheme, as a rule, was simplistic: the good guys and the bad guys get

set up against each other at the beginning of the game, you have to find a

conventional or an unconventional way to let the good guys triumph over the

bad guys, you save yourself / your girl / your pet poodle / the world and go

home. For all the talk about how adventure games at the time were typically

played by a more sophisticated / intellectual brand of consumers, the basic

structure of these games rarely went beyond the philosophy of the average

happy-ending Hollywood movie. Gilbert, instead, took his inspiration from

something like a Monty Python movie

(think back to the ending of The Holy

Grail), and ended up creating something that you might not necessarily

like or agree with, but definitely something that you will not soon forget —

or might even use in future discussions on child psychology, Freudian

concepts, and the influence of pizza on the brain of outstanding game

designers. |

||||

|

Allegedly, the puzzles of Monkey Island 2 were originally deemed

so challenging for players that some (not all) versions of the game came with

a special Monkey Island Lite mode,

cutting out a big chunk of the challenges and jokingly asserting on the back

cover that this particular mode was primarily intended for video game

reviewers. However, unlike the «normal» vs. «MegaMonkey» modes of The Curse Of Monkey Island, which

would indeed be two different design strategies for the more vs. less patient

players, the Lite mode here was

more like a joke at the expense of whiny players, since it efficiently

removed most of the challenge — and, incidentally, it was never reproduced in

2010’s Special Edition remake. This is not to say that the regular

puzzles in the game are not challenging — far from it! — but neither could

anyone insist on placing it in the category of the most challenging games

ever designed. As a rule, the complexity of an adventure game depends not so

much on the intellectual level of the designers and players, but rather on

the plain size of the game: the more

locations there are to explore, the more objects to pick up, the more

characters to interact with — the more potential combinations of actions

arise at your disposal; and while, of course, it is rarely, if ever, a

question of trying out all

theoretically possible scenarios, it may still take a lot of time before you

filter out all the moderately reasonable ones which still do not fit. From

that point of view, the second Monkey

Island obviously offered more challenge — simply because it was so much

bigger, and because the successful completion of its puzzles required, in

particular, quite a bit of jumping to and fro from one of the three islands

to the other two (a trick that would soon be implemented in a far more

revolutionary and demented fashion on Day

Of The Tentacle). As it was with the first game, the

specific difficulty of the puzzles lay in their following that very special

brand of Monkey Island Logik to the terms and conditions of which you are

obligated to wholeheartedly subscribe in order to save yourself hours of

useless frustration. The Monkey Island universe revolves around its own

inimitable axis, which requires that perilous swamps need to be crossed in

floating coffins, dogs and monkeys be carried around in the pockets of your

overcoat, and pet alligators in hotel lobbies be addicted to cheese

squigglies. Once your brain gets adjusted to this why-the-fuck-not mentality,

puzzle solving in Monkey Island 2

generally becomes demented child’s play, though there are still proverbial

tough cases, such as, for instance, the relatively infamous «monkey wrench»

puzzle where [inevitable spoiler alert!]

you are indeed supposed to use an actual monkey as an actual wrench. Is this

a truly tough and unjust puzzle, or is it fully permissible in the Monkey Island

Universe, most of which is built on puns and gags by default? Opinions here

are strongly divided, but if I were to cast a vote, I would still vote

«permissible» — though, in all honesty, at least some sort of prior indirect clue to poor Jojo’s amazing wrenching

abilities would have been nice. In other cases, the complexity of the

challenge is caused by several different conditions necessary to overcome it:

most notably, the hilarious spitting contest where you have to do at least

three different things to turn the odds in Guybrush’s favor, each of which

requires a fairly non-trivial way of thinking — and since there is no way to

learn that you need to do all three from the beginning, emotions are very

likely to run high each time that sweet victory finds itself snatched out of

your jaws along with the next burst of saliva. There are also instances when

salvation clues are received so far ahead of time that it takes quite a

brain-push to realize how they are related to your current situation (this

specifically concerns the connection between the psychedelic Dead Parent

Dance and the bony maze inside LeChuck’s Fortress). But, once again, not a

single of these situations truly defies Monkey Island Logik, and I do vaguely

remember myself being able to complete the game in the pre-Internet,

pre-walkthrough age — something that I was not able to do with Sierra’s Police

Quest, for instance. Apparently, there is an innate capacity to master

Monkey Island Logik in at least some of us, much unlike an intuitive understanding

of proper police procedure. According to standard LucasArts rules,

there are no situations whatsoever in the game where you can get stuck due to

not having fulfilled a requirement earlier, nor is there anything punishable

by death (technically, you can die at least once, horrendously executed

inside LeChuck’s fortress, but then an ingenious narrative twist immediately

brings you back to life). There are very few red herrings either, and most of

them come in the form of hilarious dialog — perhaps the funniest of these is

trying to take a philosophy lesson from your old pal Herman Toothrot on Dinky

Island, which involves naming of about 100 different potential colors for

trees and ultimately leads Guybrush to conclude that "philosophy is not

worth my time" ("I’m impressed!" reacts an excited Herman,

"it takes most people years to realize that!"). In any case, each

and every superfluous and unnecessary path of dialog here is totally worth

taking: it’s the little things like that which truly bring out the atmosphere

in Monkey Island 2. And speaking

of atmosphere... |

||||

|

It might very well be so, you know,

that the biggest difference between the first and second games actually

concerns the realm of feels. One

reason why Secret seemed a bit too

lightweight for me after having played it after the second game is that I was

struck by how much brighter it was in terms of overall mood. Both

Mêlée and Monkey Island were generally fun places — the

«hellish» experiences of Guybrush did not properly begin until the final act

of the game, and even then they were more psychedelic than truly scary. In

stark contrast, Scabb Island immediately announces itself as an unsafe

location, with LeChuck’s right hand Largo LaGrande prowling upon the premises,

the Voodoo Lady being reachable only by crossing a perilous-looking swamp in

a coffin, and a large part of the island being dominated by a huge cemetery. And that is just the beginning. There

is Phatt Island, where you have to endure jail time and come face to face with

the disgusting monstrosity of its governor (who has an actual system of

feeding tubes installed next to his bed in order to save all those precious

calories). There is Guybrush’s nightmare, during which he sees his parents

turn into dancing skeletons. There is LeChuck’s fortress, all skulls and

bones and pools of acid. Finally, there is the climactic confrontation with

LeChuck in the underground, which goes on for much longer than the battle at

the end of Secret, is far more

nerve-wrecking, and ends with a gruesome scene of dismemberment (which

somehow ends up more gruesome than the Star

Wars sequence that it so obviously parodies). It goes without saying that all these

things are deeply mixed with humor: all the darkness in the game is played

out for satirical effect. But it is still darkness, and there are moments in

the game that might genuinely scare a younger player (probably no such luck

with Secret). The Ghost Pirate

LeChuck, in particular, is probably much creepier in this installment than he

was in the first one, and unquestionably far creepier than he would be in the

sequels (where his level of scariness rarely exceeds Sesame Street level). When it comes to the big revelation scene,

no matter how much of a joke it is, some sort of shock reaction is still

guaranteed one way or another — somehow, even through a very parodic means of

delivery Gilbert’s team is able to convey the confusion over the breaking up

of the good / evil dichotomy. The «mature» theme does not exactly

stop at scariness. As others have already pointed out, there is a larger

amount of gross action (such as the spitting contest, for instance, or the

soup-poisoning incident). In one case, Guybrush finds himself obligated to

cross-dress, then have a seriously «adult» conversation with the love of his

life while still wearing a pretty pink dress. Ultimately, the universe of Monkey Island 2 seems to close in

heavier on his protagonist than the universe of Secret Of Monkey Island, and the protagonist has to react

correspondingly, often with decidedly ruthless and renegade actions, because

desperate times call for voodoo doll measures. Is this all appropriate for a Monkey Island setting? In my opinion

— absolutely so, just like the already mentioned Monty Python And The Holy Grail never shied away from disturbing

or mature imagery when it was thought necessary. LucasArts’ obsessive

fixation on comedy and humor did render them a good service for those fans

who thought that the worst thing about a computer game was when it took

itself too seriously; but the complete elimination of any sense of darkness

or danger — and remember, you couldn’t even die properly in a LucasArts game! — sometimes made playing the

games into too much of a haughty-giggly affair, leaving no space for tension

and decreasing immersion. Monkey

Island 2 is one of the few LucasArts games that is willing to open a tiny

window and let in some darkness and suspense — precisely the kind of thing

that, for instance, had earlier made Sierra’s Leisure Suit Larry 2 stand out a little from the other games of

the series by cleverly combining smut and humor with suspense. Of course, none of that is done at the

expense of the humor — and while we’re on that, let me state another

important point: Monkey Island 2

builds most of its reputation on original

humor, rather than recycled jokes and running gags from the first game

(something that really really bugs me about the post-Gilbert sequels). There

are a few lines that have been inherited from Secret ("I’m Guybrush Threepwood, a mighty pirate!" and

"Look behind you, a three-headed monkey!" among them), but they are

not overdone and just play their part of faithful shaken-not-stirred-style

tags. But there are tons of new characters with new jokes to crack; there are

useless hilarious little rituals to partake of (you have not lived if you

have not played the "100 bottles of beer on the wall" game!); and

while the end game may be laying on the Star

Wars worship a bit too thick (I

guess they were just happy they had no legal limits to the amount of stuff

they could quote), this is, in a way, just an unsubtle hint at the already

suggested Empire Strikes Back-style

nature of the game. All in all, Monkey

Island 2 continues to be a triumph of insane imagination. |

||||

|

Technical features Note: As was the case with Secret Of Monkey Island, the following section will cover (and,

where necessary, compare) both the original 1990 edition of the game and the

2010 Special Edition. Once again, no separate review for the remake is

necessary, since it changes nothing in the base game but rather just provides

a complete overhaul of its visuals, sound, and gameplay interface. |

||||

|

Truth be told, with but a

few very special exceptions the main strengths of LucasArts rarely lay in their

visual art technique, and Monkey Island

2 is no exception. Despite some pretty serious changes that took place in

between Secret and Revenge — such as fully completing

the shift from 16-color EGA to 256-color VGA and implementing the procedure

of scanning manually painted images — I cannot say that the second game looks

as drastically different from the first one as, say, Sierra’s VGA-era games

look from their EGA era, or even that the differences are necessarily for the

better. The ability to use more

colors, experiment with higher resolutions, and rely on hand-drawn material

certainly adds to the density of detail: the screens of Secret were relatively sparse, while the various interiors of

Monkey Island 2 (and some of the exteriors) have a lot more going on. But in

that particular age, «more» did not necessarily mean «better»: the various

shops on Booty Island, for instance, end up cluttered and messy, with the

hand-painted style not converting ideally to VGA resolutions. Some of this is

technically explainable by the fact that they still had to cram all the

images into about two-thirds of the screen’s regular size, in order to leave

necessary space for all the interface (more on that below) — an unfortunate

limitation that could have been avoided by redesigning the gameplay, but was not avoided, probably because Gilbert

and Co. were so proud of having invented that style in the first place. Arguably the most

impressive improvements were achieved with the animated sprites. These were

now able to be developed in far more detail, with more fluent movements and

facial gestures; the upscaled Guybrush now also looked plumpier, beardier,

and somewhat more mischievous than the short-pants teenage kid in the first

game. And special praise goes to whoever designed the image of LeChuck: the

sight of the green-faced, red-eyed, heavily bearded, spit-throwing monster

was far creepier than the authentically «ghostly» silhouette of the first

game, and contributed heavily to the already mentioned darker atmosphere. That said, I beg pardon

from all the purists by admitting that, even though I should have been

properly ruled by nostalgia at this point, I still far prefer the re-drawn

Special Edition version of Monkey

Island 2. Just like the first game in the series, it was a faithful

graphic recreation of all the backdrops, foregrounds, and minor details from

the original game — obviously, with some stylistic changes that veteran fans

did not always appreciate, but without ever losing the spirit of the original

renderings. Had the old images represented some sort of fabulous graphic art

breakthrough or featured a totally unique style, I would have had second

thoughts; as it is, I am not sorry to say that with the new graphics, the

game has become better playable even for those players who, like me, are always

ready to appreciate first-rate EGA/VGA art from the good old days. Most importantly, the new,

re-drawn Guybrush has never looked more smashingly dashing than he does in

the Special Edition: gone is the rather creepily fish-eyed, scrawny kid from Secret, replaced by a fashionably

clad wannabe swashbuckler with appropriate body weight and, occasionally, a

properly tricky glint in his eyes. This is probably my favorite version of

the guy, and it is too bad that they’d only come up with it for the very last

product to feature Guybrush Threepwood

as a protagonist (even the TellTale sequel Tales Of Monkey Island came out one year earlier, and I

definitely do not like the way GT was portrayed there). One major flaw of the

game’s graphic design as compared to the original was the near-total lack of

close-ups (I think the only one in the entire game is that of Governor Phatt

in his bed). Why they decided to omit it, despite having a larger budget and

all, is unclear: I would certainly have loved to see Elaine or LeChuck up

close at least once or twice. It sort of fits into this pet conception of

mine that graphic art was not a major priority at the time; unfortunately,

this also means that the remake had to follow suit in order to remain loyal

to the original (actually, they could not change anything because, like the

first game, the Special Edition always allows you to switch between the old

and the new graphic styles in one click, with a one-to-one correlation in all

cases). Then again, some people were allegedly not too happy with the

close-ups in Secret, insisting

that they did not match well with the regular sprites — so, perhaps, it was

thought that close-ups could ruin immersion rather than enhance it. Wouldn’t

be my way of thinking, but then I

am not Ron Gilbert (and thank God for that). |

||||

|

For the second game in the

series, Michael Land was retained as principal composer, with two more

assistant composers at his side, and the result is cozily predictable — yet

another Caribbean-influenced soundtrack, nice tunes with calypso, ska, and

reggae influences which serve their purpose but are rarely memorable on their

own, except for the main theme tunes which were carried over from the first

game anyway (e.g. the Monkey Island theme and LeChuck’s gruesomely carnivalesque

theme). Due to the increased darkness of the game, there are a few

spookier-sounding-than-usual themes (in the Voodoo Lady’s swamp, at the

cemetery, etc.), but since this is still a funny sort of darkness, the themes

are correspondingly vaudevillian, better suited for a phantasmagoric show

than a chilly supernatural thriller. And that is probably the way it should

be. In terms of music, Monkey Island 2 is probably

specifically remembered for incorporating the «iMUSE» (Interactive Music

Streaming Engine — years before the i- in the Apple products, for that

matter!) system, an innovative approach to integrate the various musical

tracks in the game. Before that, the typical scheme was that when you moved

from one location to another, one track would simply be abruptly cut off and

another would begin playing in its place; at best, in order to make things

less jarring, the first track could be quickly faded out and the next one be

faded in. Land and Peter McConnell instead tweaked the system so that the tracks

would seamlessly merge with each other, giving the first one an abrupt, but

natural ending flourish from which the next one would then emerge. This

creates an aurally pleasing continuity and lets you experience a smoothly

flowing, never ever interrupted musical background. That said, for all the

revolutionary nature of iMUSE I could hardly call it an emotionally rewarding

achievement — more like a quirky one, and there is a good reason why it never

became the video game industry’s default standart. Despite the increased

budget, Monkey Island 2 remained a

voiceless game upon release (other than a few sound effects here and there),

and the situation was only corrected with 2010’s Special Edition, for which, just

like for the previous game, almost the entire cast of Curse Of Monkey Island returned to provide their services.

Needless to say, with Dominic Armato reprising the role of Guybrush,

Alexandra Boyd the role of Elaine, and Earl Boen the role of LeChuck there is

hardly anything to complain about — and the new parts are generally just as

consistent (I am particularly happy with Roger Jackson finding the perfect

gluttonous pitch for Governor Phatt, and with Sally Clawson finding the

perfect you-go-girl pitch for Captain Kate Capsize). Perhaps the most seductive

feature of the Special Edition is that, unlike Secret, it actually lets you choose the old-school 1992 graphics

while leaving on the new soundtrack — almost creating the illusion that

Armato has been The Guybrush since 1992, when in reality his first take on

Threepwood’s character would only take place in 1997. Indeed, the new voice

soundtrack fits in with the old game so smoothly that it is pretty hard to

believe the original was not initially designed with voice acting in mind —

for instance, the game of «100 Bottles of Beer on the Wall» practically

screams for live singing and interrupting; and the "search your

feelings" dialog between Guybrush and LeChuck in the climactic

underground scene can only reach the threshold of genuine hilariousness when

it is done in proper Darth Vader / Luke fashion (I like how Armato does not

even forget to add the second, weaker "noo..." to the first big

one... we all remember that Luke actually says NO! twice, don’t we?). As

such, this is another argument that the Special Edition does not so much

reimagine or redefine the original game as it simply completes it, precisely the way it should have been completed in

1992, without «corrupting» the experience in some sort of bland 21st century

manner. Excellent work. |

||||

|

Interface The original game added a

tiny twist to the typical SCUMM interface — by slightly shortening the number

of available verbs to pick from (e.g. eliminating "turn on" and

"turn off" for their redundancy, and maybe also because options such

as "turn on Captain Kate" could be seen as really ambiguous) and using the freed-up space for a larger

inventory window in the bottom right corner, in which the actual objects were

now pictographic rather than just listed verbally (though, frankly, sometimes it would be

easier to properly identify an object by reading its name than by seeing its

pixelated contour). That’s pretty much all there is to it.

The Special Edition, just like it did for the first game, converted it all to

a full-fledged point-and-click experience, freeing up valuable space for

onscreen images and also correcting a relative inconvenience in Secret, where you had to alternate

between left- and right-clicking the mouse on the object to do different

things with it; now, whenever you click a hotspot, it immediately shows you

all the potential options to choose from ("look", "pick

up", etc.). Needless to say, this style eliminates the last chance at

actual choice that you had with several different verbs, but, let’s face it,

the damage was done with the elimination of the free parser: frankly, it does

not much matter if you get to choose from "use", "push",

and "pull" or if you just condense them all to a single

"interact with". Give me parser liberty or give me point-and-click

death, leave me alone with your insignificant little compromises. Overall, it does not matter much

because most of your troubles will come from the necessity of finding the

relevant objects and choosing the right ones, rather than figuring out what

precisely to do with them. There are occasional bits of trickiness — for

instance, in order to escape one particularly dire situation you need to time

your, um, expectorating strategy just right — but usually it is all very

straightforward. The storyline does not even involve any special «mini-games»

à la Insult Swordfighting of

the first game: everything here is strictly wit-based, no grinding or

repetition involved whatsoever (addition of these elements to the later

sequels, as a rule, tended to be quite controversial). |

||||

|

It is a little sad that Monkey

Island 2 does not work fully

well on its own: without playing Secret

first, you will remain in the dark as to some of the in-game jokes and character

backstories. And, frankly speaking, any work of art with the number ‘2’

slapped on it screams to be a little underappreciated (with the exception of The Godfather 2). But then there is no

reason why you shouldn’t — and you should — simply take the first two games

together and treat them as a self-sufficient, cohesive, and dynamically

developing dilogy, growing ever more deep and intriguing, rather than more

boring and predictable, as the story gradually unwinds. The ensuing sequels,

good or bad as they were, were notably different from the vision of the

series’ creator — in my opinion, more strongly feeding upon the legend rather

than adding to it — but the second game was the one that expanded, perfected,

and essentially completed the basic «Monkey Island construction set», as well

as made it possible to think and theoretize about the game in almost serious

philosophical terms. (Not that I am demanding we all make good use of this

possibility: for all his awesomeness, Ron Gilbert is no Terry Gilliam, and if

he were, he would probably make his name somewhere other than the videogame

industry). As a brief addendum, I also must repeat that the 2010 Special Edition

of the game should be quoted as a textbook example of how to make classic old

games palatable for modern audiences without sacrificing their original flair

and spirit. With the modern and classic looks fully integrated with each

other, you can enjoy it as a museum history piece one moment and as a fully

relevant and enjoyable interactive adventure the next one. If there is one

thing that might seem «dated» about Monkey

Island 2, it is simply that recent times have not seen that much by way

of great comedy entertainment in plot-based video games, most of which now

take themselves way too seriously. So the only way to get out of this tight

spot is to look behind you, and catch a glimpse of that three-headed monkey

before they take it out of your Steam account. |

||||