|

|

||||

|

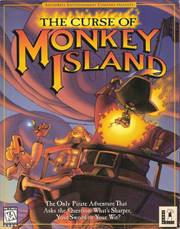

Studio: |

LucasArts |

|||

|

Designer(s): |

Larry

Ahern / Jonathan Ackley |

|||

|

Part of series: |

Monkey

Island |

|||

|

Release: |

November 1, 1997 |

|||

|

Main credits: |

Programmers: Jonathan Ackley, Charles Jordan, Chris J. Purvis |

|||

|

Useful links: |

Complete

playthrough (8 parts, 468 mins.) |

|||

|

It is not entirely clear to

me why, of all the possible paths to follow, LucasArts decided to choose a

sequel to the first two Monkey Island

games in the fall of 1996. Neither of the two was exactly a bestseller, which

should have mattered at the time that some of the studio’s newer games, such

as The Dig and, especially, Full Throttle were finally beginning

to move hundreds of thousands of copies. Worse, both clearly reflected the

coherent and unique vision of their chief designer Ron Gilbert, who, as of

1996, was no longer employed at the studio and could, at best, offer creative

advice from a distance (which, as far as I know, he did not, though he did go

on record praising the game long after it was released). We should probably

just ascribe this to a certain mystical aura that surrounded Monkey Island more than any other

LucasArts achievement — and at the center of which was situated LucasArts’

single most memorable, adorable, and legendary playable character, Guybrush

"I want to be a pirate" Threepwood. I do not know just how much fan

pressure the studio had to endure, but I do easily believe that sending in a

letter saying BRING GUYBRUSH BACK

would be a far more natural thing to do in the mid-1990s than, for instance, BRING BACK ZAK McCRACKEN or BRING BACK BOBBIN THREADBARE (the

latter actually gets a sarcastic reference at the end of this game, more or

less hinting at the truth — some adventure game characters die in body and spirit, while others get lucky

enough to pass on into legend). By far the oddest and riskiest decision

was to place the renewed fate of Mr. Threepwood into the hands of two

employees who had very little to do with Monkey

Island in the first place. Larry Ahern had been with LucasArts since 1991

and had indeed worked on LeChuck’s

Revenge — as graphic artist and animator, which is a pretty long way from

story writer and general game designer. Jonathan Ackley came in even later,

in 1993, and worked as a programmer on several titles, from Day Of The Tentacle to Full Throttle and The Dig. Neither of the two had, in fact, had any prior

experience designing adventure games, meaning that putting them on the

project was quite a massive gamble for the studio — and, as I shall try to

show below, the decision had both positive and negative effects. The main and quite objective positive

effect was, of course, that the game became a commercial success — a far more

decisive one than the sales results of the first two titles. At first, it

fared much better in Europe (especially Germany) than in the States, but

eventually the pace picked up, turning Curse

Of Monkey Island into the best selling unit of the entire franchise, a

success that its sequel, Escape From

Monkey Island, already failed to repeat. Even more importantly, perhaps, Curse Of Monkey Island became the

default game to introduce a revamped and refurbished Guybrush Threepwood to a

whole new generation of young gamers — the generation which already had much

higher technical demands for a good game than the previous one, expecting

their Guybrush to look all sharp and dandy in high graphic resolution and talk

in an actual human voice. For many of the modern nostalgic gamers out there, The Curse Of Monkey Island remains the

definitive entry in the series precisely because it was their first encounter

with the absurd and twisted world of three-headed monkeys, insult sword

fighting, and rubber chickens with pulleys in the middle. Because of these specific

circumstances, saying anything negative about the game in certain circles is

liable to getting you ostracized. Yet, this still being a relatively niche

topic and all, I will (ironically) «gather the courage» to say this from the

start: both as a challenging adventure game and as a respectable artistic

entry in the Monkey Island canon, The Curse is a deeply flawed,

substantially unsatisfactory title, with many inventive and inspired «little»

ideas which never really gel into a big, cohesive, meaningful whole.

Actually, it is its principal flaw which is quite big, cohesive, and

meaningful. The first two games, created by Gilbert, were (generally

successful) attempts to create a large, sprawling meta-world of mock-fantasy,

one that would both celebrate our knack for creating an imaginary past for

our species and ridicule it at the same time. Conversely, The Curse Of Monkey Island is an

attempt to create a Monkey Island

game — no less and no more that. Of all LucasArts games ever created,

this one (and its even less satisfactory sequel, of course) is the

quintessential epitome of the «give the people more, more, more of what they

want» principle — not coincidentally, unlike the first two games, which sold

poorly despite getting rave reviews upon release, Curse seems to have been slightly more popular with fans than

critics (though I may be mistaken here, since I am only basing this judgement

on a very small number of mixed reviews). Yet there is a reason why the names

of Ackley and Ahern are rarely, if ever, mentioned alongside the names of

such acclaimed LucasArts «visionaries» as Ron Gilbert, Dave Grossman, or Tim

Schafer — or even such less famous, more «cult» names as Loom’s Brian Moriarty. This is because these names, in all

honesty, simply do not matter. Names matter when inscribed on a work of art; The Curse Of Monkey Island is a fine,

enjoyable piece of product. Perhaps it works better when taken completely

outside of context — this is something that should be confirmed for somebody

who played this game prior to the

first two, and preferably was older than 12 years at the time — but,

unfortunately, it makes even less sense when it is taken outside of that

context. Let us take a closer look now and try to determine what exactly went

wrong here, and whether it was at all possible to not let it all go wrong in

the first place. |

||||

|

Content evaluation |

||||

|

The first and most obvious

problem of the story that Ackley and Ahern had to write for the game is that

the story... simply could not be written. At the end of LeChuck’s Revenge, it is made perfectly transparent that the

entire universe of Monkey Island

is, in fact, little more than a fantasy, explicitly played out or implicitly

and covertly imagined in the brains of two young brothers, fueled by the

visual wonders of an amusement park. You could

go out of your way and interpret the whole thing somewhat differently, but

then you could also choose to believe, if you so wanted, that Prince Hamlet

really feigned his own death in order to go undercover under the rule of King

Fortinbras so as to seek out the true

killers of his father. For all intents and purposes, the second Monkey Island game closed the book on

Guybrush Threepwood and put it under a heavy rock, which at least required a

bunch of heavyweights to lift. Ackley and Ahern were no

heavyweights, so, when pressed for a proper way to resume the story, they

chose the simplest of all possible approaches — when all else fails, bullshit

your way out of the situation. At the start of the game, Guybrush appears

adrift on the ocean, without a single clue about whatever happened in between

his discovery of «Big Whoop» and the present time. Approximately three

quarters of the game are then spent in complete ignorance, as Guybrush

merrily goes around on his business. Then, in the last act, as the Ghost

Pirate LeChuck materializes once again and decides that he’s got some serious

time to spare, he delivers before the bedazzled Guybrush a story so

convoluted, so full of holes, so utterly meaningless and unfunny, that, in

all honesty, it might have been more honest to just leave the mystery a

mystery. Actually, the main plot of the game — to which

Guybrush’s lonesome drifting on the ocean and the crazy final act are only

related on a purely formal level — has nothing to do with «Big Whoop»,

LeChuck, or Guybrush Threepwood’s troublesome family relations. In the cargo

hold of LeChuck’s ship, Guybrush finds a beautiful diamond ring, which he

promptly gifts to Elaine Marley, his fiancée, as a wedding gift.

Putting it on, Elaine is struck by an old voodoo curse and turned into a gold

statue — meaning that most of the game, naturally, will be spent by Guybrush

trying to figure out how to undo the spell. The same way most of The Secret Of Monkey Island was spent

trying to pass the Three Trials, and most of LeChuck’s Revenge was spent putting together the map pieces for

the «Big Whoop». Grumbling naysayers sometimes protest

at this point specifically, complaining that Ackley and Ahern went against

Elaine’s character, transforming her into a Damsel in Distress. This aspect

does not bother me in the least: Elaine’s character as such, the way it is

presented in the introduction, is as strong-willed and sarcastic as ever

("Let’s face it, LeChuck, you’re

an evil, foul-smelling, vile, codependent villain and that’s just not what

I’m looking for in a romantic relationship right now"), and her

transformation into a statue — which certainly does not show any weakness of

character — simply takes her out of the game for the majority of it, which

is... more or less the same status she’d occupied in the previous two games

as well. Besides, LucasArts would clearly overcompensate for this by vastly

enlarging Elaine’s role in Escape From

Monkey Island three years later, so let bygones be bygones. Nor, of course, should we really get

angry that the plot is, after all, merely an excuse for introducing the

game’s many whacky secondary characters, locations, and puzzles — this

strategy is more or less in agreement with Ron Gilbert’s original vision

(though a little less in agreement with his vision for the second game). As

usual, over the course of the game Guybrush is going to visit several islands

(most of the action takes place on the rather lacklusterly-called Plunder

Island and Blood Island) and meet a solid mix of both returning fixtures (the

Voodoo Lady; Stan the Salesman; the Cannibals of Monkey Island) and new

presences (too numerous to mention in a single sentence). The jokes, puns,

gags, surrealism, absurdity, irony, parody just keep coming. So what the hell

could be the problem? To give a precise example, let us

rewind all the way back to the introduction. We open up on Guybrush drifting

across the open sea in a strange kind of ocean craft, vaguely resembling a

flatiron. He is writing in his diary: "Really, really thirsty now. If only I could have a small drink of

fresh water, I might have the strength to sail on." (An entire

bottle of ‘Monkey Spring Water’ floats past us in the foreground, but

Guybrush is too busy writing to notice.) "If I could reach land, I might find water and some food. Fruit,

maybe... some bananas..." (A bowl of fruit and an entire bunch of

bananas float by, without Guybrush noticing.) "Oh, why do I torture myself like this? I might as well wish for some

chicken and a big mug of grog for all the good it will do to me." (A

live chicken standing on a barrel of grog floats by.) The entire sequence is mildly funny, as

a nice enough representative of the "expect the unexpectable"

comedic trope. But somehow, it is nowhere near as funny as the opening to Monkey Island 2, where Guybrush has to

explain his entire backstory to Elaine while hanging on to a rope with one

hand and clutching a heavy chest in the other ("It’s kind of a long

story" – "It’s OK, I’ve got time"). The reason is simple

enough: we are well aware that the floating water bottle, fruit, and chicken

on the barrel make absolutely no logic sense whatsoever — whereas the

rope-hanging sequence promises a potentially explainable intrigue (which,

indeed, is eventually explained). This does not mean that Gilbert’s Monkey Island never included

logic-defying absurdities out of nowhere (remember the three-headed monkey?)

— but it is somewhat symbolic of the respective priorities of the Gilbert-era

and the post-Gilbert era games. The priorities of The Curse Of Monkey Island are made clear from the get-go: cram

as much funniness per square inch as physically possible. It doesn’t matter

if they are not all that funny, or

if they do not make any kind of sense, it does not matter if they are

recycled or they are fresh, it does not matter if they are running gags from

older games or something invented on the spot — just DO IT. Some of the

characters, like Murray the Evil Skull, are introduced into the story with

the exclusive function of being funny and nothing else; others serve some

nominal function or other, but essentially are still there to be funny and

nothing else. Every dialog line spoken by Guybrush or by somebody else — I

mean, almost literally every one —

has to be funny. Or die trying. Never in the field of human humor was so much

owed to Guybrush Threepwood. And guess what — this is not

necessarily a good thing. Behind all the puns and gags, even while on Plunder

Island, where my goals still remain reasonably clear (get together a crew,

get yourself a ship — the same as in Secret,

actually), I often find myself at a loss about what to do, simply because I

happened to miss my latest directives behind the incessant, interminable wall

of hit-and-miss hilariousness. I’m not even saying the jokes are not funny

(though with this kind of quantity, quite a few are bound to be unfunny, as proven by the most basic application of

the probability theory) — I am saying that after a while, a certain numbness

sets in when you just can’t take any more. It gets worse by the time you get

to Blood Island, where the plot becomes even more twisted and even less

logical, and it reaches a nightmarish peak in the final act, with LeChuck’s

«Carnival of the Damned» that feels like a Sesame Street version of an

Hieronymus Bosch panorama of the Apocalypse (and no, it is really nowhere

near as wonderful as this description could suggest). Two things in particular irritate the

hell out of me. One is the endless stream of self-references — ironically,

even if the game seems to have attracted far more novice fans than the first

two, it reads as if it was very specifically designed with exclusively the

old fans in mind. It’s as if Ackley and Ahern had made themselves a detailed

check list in advance and spent most of the time crossing items off the list.

The return of Wally the Cartographer? Check (he was not blown up, but

recruited by LeChuck to become his next henchman). Insult sword fighting from

the first game? Of course it’s back, with a fresh bunch of new insults for

all the fans of "You fight like a cow" out there. The Voodoo Lady

and Stan the Salesman? Doing fine as usual, completely predictable with their

merchandising shtick. Pirate jokes? Check. LeChuck taunts? Check. Stupid sea

shanties? Check. Ridiculous contests? Check. Gags that go all the way back to

1990? Check. In fact, the only reason that some of the original characters from the first two games have not

returned (like Meathook, for instance) is that they were probably saved up

for the next sequel. The other thing is that, for all of

Gilbert’s surrealistic whackiness, the man knew where to draw the line. There

are moments of sheer absurdity in

the first two games — such as, for instance, Guybrush’s "use staple

remover on tremendous dangerous-looking yak" confrontation in the

Governor’s mansion — but most of them, when you stop and give it some

thought, have an inner intelligence, parodying or ridiculing some parallel

absurdity in real-life universe (in this case — the proverbial «adventure

game logic» as such). Much, if not most, of the sheer absurdity in Curse Of Monkey Island is absurdity

for absurdity’s sake, which could, perhaps, be taken in small doses, but

certainly not when you have to pretty much live inside this absurdity —

Guybrush’s hijacking of The Sea Cucumber, with its gorilla Captain LeChimp,

is a particularly dumb episode, as is almost everything that happens on Blood

Island and specifically the very last act of the game (Guybrush’s interaction

with Dingy Dog and Wharf Rat at LeChuck’s ghostly carnival), where occasional

genuinely funny jokes are presented in an overall setting of WHY WHY WHY OH

GOD WHY???? Given that Ackley and Ahern almost

literally throw everything at the

wall, some of it does stick. Here, off the top of my head, is a brief list of

mini-motives that actually work: 1) Murray the Evil Skull (the game’s single

most brilliant invention, unfortunately also run into the ground way before

the game is over, but... "you’re about as fearsome as a doorstep" –

"is it a really EVIL-looking doorstep?" gets me every time); 2) the

pirate actors rewriting Shakespeare ("now that you have confirmed that I

have produced a work of unredeemable trash... I’m more or less guaranteed to

have a financial success on my hands") — this is at least a reasonably

sharp jab at certain contemporary theatrical practices, which is why it’s

actually funny; 3) the lactose-intolerant volcano worshipped by the paradigm-shifting

vegetarian cannibals on Blood Island — again, mainly because this kind of

humor makes deep sense (even deeper in 2020 than it did in 1997). And that’s... about it, really. Every

other part of plot ranges from «okay, ha ha» to «passable» to tedious to

downright disgusting (there is a particularly ugly moment where you have to

take a tattoo map off the back of an obnoxious guy by literally broiling his

back in the sun and peeling off his skin — what the hell? I’m all for dark

humor, e.g. "he’s had a sudden and unexpected relapse of death", but

this is rather sadistic non-humor, which needlessly makes Guybrush into a

much bigger asshole than he’s ever been). There may be decent small jokes and

puns spread throughout the desolation — it’s only the little things that can

be the saving grace of this game — but while they do make the time pass by

more cheerfully, it is definitely not enough to positively color the overall

impression of the game. Finally, while the indignation of some

fans over the surprise ending of Monkey

Island 2 may be understood (but should hardly be shared), I’d take a

hundred endings like those over the chaotic mess that is the ending of Curse. If you are not familiar with

it, I will just say that it involves a giant «Dynamo-Monkelectric Snow

Monkey», and that should probably be enough. What happened to the good old

innocent days of bottles of voodoo root beer? What we have here before our

eyes is a horrendously twisted, needlessly complicated,

grotesque-beyond-measure expansion of the Monkey

Island universe in every possible direction — which is a downright

catastrophic decision for a game that originally grew out of a pirate-themed

amusement park. (Ironically, but perhaps predictably, much the same fate

would later befall the Pirates Of The

Caribbean franchise, whose first installment had a pretty decent plot

loaded with innocent fun, but each new movie just kept on piling stuff up and

around until the whole thing simply imploded onto itself). Of course, an argument always can be

made about overthinking the whole deal — instead of simply taking The Curse Of Monkey Island for what it

is, an unpretentious piece of lightweight entertainment, and enjoying the

hell out of it. But, as I said, this is only possible if you somehow manage

to completely detach the grappling hooks that join Curse with the Gilbert-era games — and this, in turn, is only

possible if you have never played the Gilbert-era games in the first place,

which, in turn, is stupid precisely because

the game is so goddamn self-referential all the time. I sometimes wonder just

how different things would be if I happened to play the games in backward

order; but then again, putting your underwear on after your trousers is also

an option that can lead to unpredictable results and unique experiences...

what was the suggestion again? |

||||

|

Unfortunately, the

arbitrary whackiness of the game has its first and foremost reflection on the

game’s system of puzzles — which is also quite arbitrarily whacky. The first

thing you should know is that The Curse Of Monkey Island comes in two flavors — regular and

«Mega-Monkey», promising the player extra challenging adventure goodness;

naturally, the seasoned adventurer shall not settle for anything less than

«Mega», but the seasoned adventurer should be wary that the mega-er the game

is, the more surrealistic, cartoonish logic it is going to throw at you, some

of which goes way, way beyond anything Ron Gilbert could ever have imagined

in his most feverish dreams. And this is not a compliment. The challenges begin as

almost deceptively simple — the Prologue, which plays out the same way in

both versions, is a breeze, more of a gentle tutorial, really, which just

shows you how to use the dialog system, how to pick up and use objects, how

to hunt for hotspots, and how to play a simple mini-game (using a cannon to

shoot up boats with ghost pirates). The tables turn on you, however, once you

finish your preliminary investigation of Plunder Island and begin working

toward achieving your actual goals. This is where the game veers into

decision after decision that can be reached, in my opinion, only through

sheer luck or diligent perusal of every available point-and-click option. How to defeat the Eddie van

Halen-level pirate at banjo? Do something that defies not only common sense,

but even all the hitherto explored pathways of Monkey Island logic. How to

pull closer a dangling rope in order to escape quicksand? Find a solution in

the style of Sierra’s Incredible

Machine, no less. How to snatch a gold tooth from one pirate to present

it to another one? Welcome to the «Golden Tooth Puzzle», perhaps one of the

most famous cases of the much-maligned «adventure game logic» (almost as

famous as the Goat Puzzle of Broken

Sword, the Rubber Ducky puzzle of The

Longest Journey, and the Cat Hair Moustache puzzle of Gabriel Knight 3). If you solve the

«Mega-Monkey» version of it without a walkthrough, you should apply as

designer for whoever it is that currently holds the right to the entire

franchise. Just like the story itself, the puzzles

are hit-and-miss: for each Gold Tooth Puzzle, you get something a bit more

reasonable and fun — for instance, getting out of the snake’s belly requires

you to produce a perfectly natural concoction (the fact that you must mix it inside the snake’s belly is perfectly

acceptable within the parameters of the Monkey

Island universe), and using a swarm of parasites to get a certain pesky

pirate out of the barber’s chair is something that would spring to mind quite

naturally. Unfortunately, we tend to remember such games by the hours spent

in frustration, trying to solve the virtually unsolvable, rather than the

minutes spent logically deducing the probable; and the Ackley / Ahern

approach to Monkey Island is heavily

tilted toward the former rather than the latter. Do not even get me started

on the final act, all of which operates on some sort of demented William S.

Burroughs-style action mechanism (if you actually did complete the Disgusting

Snowcone puzzle all by yourself, you must have a really good dealer). In between the regular puzzles, you

also get a small bunch of «special» ones — a small variety of mini-games,

most of which have their good and bad sides. One involves winning the first

part of the banjo contest, where you have to pay close attention to the

strings picked by your opponent and repeat the melody (think of this as a

prophetic anticipation of GuitarFreaks

and Guitar Hero, if you wish) — a

challenge that at least makes sense (though it gets tedious on the

Mega-Monkey level). Another is the return of Insult Sword Fighting, which was

probably brought back due to its popularity with the fans — except they did

not bother at all changing even the slightest thing about its mechanics,

simply slapping it back on exactly

the way it used to be in the first game, and I am not sure how this could be

regarded as a good thing. The third mini-game actually comes

packaged together with Insult Sword Fighting — it’s essentially a spoof of

micro-management strategic games (and maybe a bit of Sid Meier’s Pirates!), where you have to

constantly upgrade your guns after winning each sea battle, in preparation

for mightier opponents. The best thing about this part is probably the names

of the cannons — ranging from ‘Holemaker Deluxe’ to ‘Paingiver 2000’ — but

the mechanics of both the battles and the bartering system is exactly the

same with each new turn, meaning that the «spoof» element is what is

essential here, not the actual fun of playing. That said, I don’t think I want to get

too mad about the game’s challenges. In the end, all of them are doable. Even

the Disgusting Snowcone puzzle, as stupid as it is, will be eventually

overcome through trial and error — how hard can one point-and-click puzzle

be, after all, when you are limited by three NPCs on a single scrolling

screen and a small bunch of inventory objects? The main flaws of the game are

not in its puzzles; in fact, as far as puzzle design is concerned, you could

easily call Curse a pretty damn

good game — though as a world, it is a relative disaster. |

||||

|

The Curse Of Monkey Island has one and only one dimension, and that

dimension is humor. You could try and say that about the first two games as

well, but you’d be dead wrong — in exactly the same way as Ackley and Ahern

were wrong when they went about faithfully capturing all the superficial

features of Ron Gilbert’s world, and all but completely missing out on what

was invisibly present under the surface. The original Monkey Island was tremendously funny, for sure, but it could also

be subtly mystical, tense, even creepy: for all the stereotypical cheesiness

of all that Caribbean voodoo imagery, Gilbert never forgot that his favorite

amusement park could also scare the shit out of you under certain conditions.

Most importantly, he never forgot that somewhere underneath all that cheese

there was a seed of something genuine — man’s fears, superstitions,

psychological terror of the unknown and the unfamiliar. If you have played

these games as a kid and have never been creeped out even once, be it onboard

LeChuck’s ghost ship, or in the lava-lit hell under Monkey Island, or in the

Voodoo Fortress, you must have been a really

jaded, cynical kid, and maybe you enjoyed torturing kittens, too. The Curse Of Monkey Island does not have even a single moment of genuine

creepiness. The Ghost Pirate LeChuck has been turned into a complete

caricature of his former self (not surprising when your right hand mate is

Dinghy Dog); the Voodoo Lady’s abode is guarded by the equally caricaturesque

Murray the Evil Skull and prominently features a broken chewing gum machine

and an inflatable alligator (compare the far more, ahem, realistic voodoo entourages in the first two games); and even

Death itself has been turned into a puzzle-solving mechanism which can be as

recurrent as you wish it to be. Again, none of this would

be all that bad if the game were a self-sufficient title; but since it so

obviously takes pride in being a

legitimate sequel to the first two, reintroducing so many of its characters,

tropes, and motives, comparisons are inevitable. Besides, believe it or not,

there may be such a thing as «fun

overdose». At a certain point, the two extremes meet, and «funny as hell»

becomes «abysmal», which is all about the game’s final act (Guybrush trying

to grow up again at the Carnival of the Damned). There are, of course, lots of very

funny individual jokes in the game, which I could quote until morning.

("Why would you sign on with a

ship of the living dead, Wally?" "Well, at first I had some misgivings about it, but thanks to

LeChuck’s seminars, motivational lectures, and audio-books-on-parrot, I’ve

become a vicious corsair! You can

too! Ask me how!") There

are also lots of very unfunny individual jokes, which I could quote until the

evening. ("Are you wearing a fake

beard?" "Actually, it’s a

highly sophisticated beard weave, made from the chest and back hair of real

pirates!") — and both of these are just from the opening dialog with

Wally, even before Murray the E-V-I-L Skull moseys along and becomes the primary

mascot of the game. Unfortunately, when your «atmosphere»

consists almost entirely of jokes, and when the entire game eats, sleeps,

breathes, and shits jokes, this does not make up for much of an atmosphere.

Plunder Island is... funny. Blood Island is... funny. A bit darker than

Plunder Island (mostly because of the colors), perhaps, but still... funny.

Carnival of the Damned is... funny to the point of vomiting. The Voodoo Lady

is funny. So is Stan the Salesman. So is Griswald Goodsoup. So is Dinghy Dog.

So are the singing pirates ("We’ll

fight you in the harbor, we’ll battle you on land, but when you meet singing

pirates, they’ll be more than you can stand" — wait, no, not funny.

Whoever wrote that pirate song should be keelhauled, honestly). And this is

not Day Of The Tentacle-level funny

— much, if not most, of this humor is not really smart humor, it’s just... jokes. The pirate jokes in particular

are getting quite stale, har har me hearties. I honestly feel like I could write an

entire dissertation on the artistic differences between the Gilbert version

of the Monkey Island universe and

its formalistic projection in the post-Gilbert era — except that there would

probably be no audience for it, so I shall simply wrap it up with another

small bunch of analogies. The relation of LeChuck’s

Revenge to The Curse Of Monkey

Island is like that of Black Sabbath to Candlemass, Gone With The Wind to Scarlett,

Psycho to Psycho II — art that diligently copies the main features of its

predecessor without being able to copy its genius, because, well, some people

are geniuses and some people are Jonathan Ackley and Larry Ahern. ’Nuff said. |

||||

|

Technical features |

||||

|

The only true advantage

that Curse Of The Monkey Island had

over the two games — an advantage that has, in retrospect, been reduced to

ashes after the release of the remade versions — is that it was released in

1997, not 1990 or 1992, which, among other things, meant a completely

reworked and improved graphic engine. For all of Larry Ahern’s flaws as a

game designer and dialog writer, I certainly cannot blame Larry Ahern as a

graphic artist, which is what he began with at LucasArts and which, honestly,

is what he should have stuck to all along. (One should also not neglect the

contributions of Bill Tiller, who was largely responsible for the artwork in

both Full Throttle and The Dig two years before). Fortunately for us all, in

1996–1997 there was still relatively little incentive for adventure games to

go 3D (poor, poor Escape From Monkey

Island!), and full-motion video was obviously out of the question for

LucasArts’ worlds of whimsical fantasy — so the only remaining alternative

was to go full-out cartoon style. Here, Ahern and Tiller refuse to follow in

Sierra’s Disney-worshipping footsteps and set out on an individual path — the

style of the background drawings is not immediately reminiscent of any

particular cartoon prototypes (though, honestly, I am not that much well-versed in the history

of animation to make an expert judgement). In any case, what matters is that

the game is beautifully drawn — and even though it has, so far, eluded

remastering, all the backgrounds still look quite dazzling on modern

monitors. Vibrant colors, realistic shadows, clearly defined shapes,

meticulous attention to detail, you name it. My only complaint is that,

keeping up with the «take everything up to eleven» principle, most of the

screens look even more cluttered with stuff than it used to be in the

previous games; the streets and squares of Plunder Island, in particular,

look something like Russian country houses where people traditionally dump

all of their city stuff that they are too reluctant to just throw away. With

so much random stuff occupying your screen, it is sometimes hard to make out

directions, not to mention the traditional national pastime of Hotspot

Hunting, which can become a nightmare under such circumstances. Character sprites are also

carved out beyond reproach — well, almost

beyond reproach, because here, too, the game loyally follows the principle

of Total Comedic Exaggeration. Mr.

Threepwood, in particular, underwent some serious surgery, having literally

been stretched out as a gummy figure — lean and lanky, almost twice his

original height and just as emaciated (that’s what a few weeks adrift at sea

will do to you in the Monkey Island

universe, I guess). Nevertheless, he still somehow manages to look like a

Guybrush should, which is harder to say about his sweetheart Elaine Marley —

now dressed in full pirate gear, sporting a rather grotesque huge head of

hair, and with most of her face occupied by either her eyes or her lips, making

her probably the most expressive, but also the most unnaturally looking NPC

in the game. Likewise, the appearance of LeChuck has also been refashioned —

now, with his beard twice as large as his face and his face taking on a

vaguely insectoid / reptilian shape, he totally looks like a funny doll, much

less imposing even in close-up cutscenes than he was as a tiny, limping

sprite back in LeChuck’s Revenge. That said, all the sprites

and animations fit in perfectly well with the game’s comedically enhanced

spirit. There are also far more close-ups and cut scenes this time,

demonstrating the full potential of LucasArts’ animators — the introduction

scene, in particular, plays out almost like a full-fledged cartoon, with tons

of action, explosions, and stuff, a stark contrast with the far more humble

introductory settings in Monkey Island

1 and 2. In short, it is not

difficult to see how easily the game could have dazzled teenage (or even

adult) imagination back in 1997: with its release, LucasArts had finally

(once again) caught up with Sierra in terms of visual awesomeness. And even

if, as you might have already guessed, the game itself will never occupy a

top spot on the LucasArts shelf for me, I do wish for it to eventually get

the same remastered treatment that Day

Of The Tentacle and Full Throttle

have already received — both were graphically inferior to Curse when they came out, but now look

«comparable» in their remastered states, and it is somewhat unjust that one

of the most graphically advanced games for its time still remains in exactly

the same situation that it was almost 25 years ago. |

||||

|

I must honestly say that,

no matter how many times I play the game (well, not a lot, actually), I

cannot remember a single thing about its musical soundtrack — well, other

than the main theme playing over the credits, of course, which is not exactly

new. This is actually a little weird, because if there was one creative link tying the game to

its past, it was composer Michael Land, the creator of iMUSE and overall nice

guy. But everything that he wrote for this game barely registers — the themes

are usually quiet, background-ish, unassuming, repetitive, and even less

memorable than before. Oh, and apparently a lot of old fans love ‘A Pirate I

Was Meant To Be’, but while the associated task (find a way to disrupt the

blasted buccaneers’ rhyming scheme) is fun, the song itself is just one more

of those «hey, it’s a pirate-themed game, we knew you folks wanted to have

another pirate-themed game for us, so here’s another pirate theme for you!»

moments, ahoy there matey and all. So to hell with the music

and let us just talk a bit about the

single most important and monumental achievement of the whole thing — the

addition of a full voice cast for the game. While I may be wrong here, I do

believe that it was the voice acting thing, and nothing else, that really

sold the whole thing back in 1997. For the first time ever, we could hear

Guybrush Threepwood talk — and not just talk, but talk with the voice of

Dominic Armato. If you have never seen Dominic Armato, check out some of his

videos on YouTube (apparently, he is a food critic most of the time) — he

literally is a real-life Guybrush

Threepwood in all but physical appearance (in which, ironically, he is a bit

more reminiscent of the Ghost Pirate LeChuck, which is fine ’cause they’re

brothers anyway), and he nailed the role perfectly upon being hired by

LucasArts at the tender age of 21. Just about every character

feature and emotion that we could have ever suspected in Guybrush Threepwood

is expressed by Armato with perfect naturalness. He typically delivers his

lines at breakneck speed, conveying the character’s hyperactive exuberance,

but at the same time manages to transmit an air of cute naïvete and

constant excitement of a curious young person suddenly finding himself in all

sorts of amazing situations. And

when necessary, Armato’s Guybrush can be mischievous, cynical, even downright

mean, without undergoing any sort of personality transformation — he’s simply

this kind of multi-faceted person, smarter than he looks on the surface and

easily adapting in defensive ways to dangerous or insulting situations. He

really was one-of-a-kind from the very start, but Armato made him come to

life in a way in which the old «mute» games never could. The rest of the cast is

just as — well, nearly as (just to

stress the arch-awesomeness of Armato’s incarnation) — impressive. British

actress Alexandra Boyd is the flamboyant, temperamental Elaine, even though

she has to spend most of the game as a mute golden statue (or bound and

gagged in the last act). Terminator

veteran Earl Boen is Captain LeChuck, sputtering out his piratey lines in the

most iconic piratey voice possible (though I sure wish he was given less

corny lines). And Leilani Jones, whom I had previously only heard as Malia

Gedde, the high voodoo priestess-cum femme fatale of Sierra’s Gabriel Knight, is somewhat ironically

cast as the Voodoo Lady, as if to specifically spoof her tragic image in that

game — whether or not she is in on the joke, she gets into both roles with

equal gusto; her Malia is every bit as sympathetic as her Voodoo Lady is

hilarious. Of the other cast members,

worth a special mention are Denny Delk, our most beloved Hoagie from Day Of The Tentacle, shedding off all

signs of lethargy and transforming himself into Murray the Evil Skull

("ROLL through the gates of Hell!") with all the verve that a

demonic limbless set of bones can muster; Neil Ross as Guybrush’s old friend

Wally, as wimpy and nerdy as a geeky cartographer training for a life of

undead piracy can be; and my own favorite, the charming old guy Kay E. Kuter

as Griswald Goodsoup, the owner of the Goodsoup hotel — again, I guess it’s

just me, but it is difficult not to see his performance as a parodic «answer»

to his gloomy, doom-laden stunt in Gabriel

Knight: The Beast Within, where he was spooking poor Grace Nakimura in

all seriousness with the vague menace of werewolves. Here, too, he seems to

be presiding over a congregation of dead bodies and ghostly apparitions — but

this is Monkey Island, the only

serious thing about which is the impressive budget they had to spend on all

these stars of voice acting. It is easy to see how the

strength of this cast alone, back in 1997, made The Curse Of Monkey Island into the one single Monkey

Island game to rule them all by definition. Who cares about the lack of

originality, the recycled corny humor, the disappearance of dark themes, when

all these wonderful actors finally make your favorite characters come to life

like never before? And that was the way it seemed to be destined to stay...

that is, until the remastered versions of the first two games came out in

2009-2010, bringing back the exact same

cast: Armato, Boyd, Boen, Jones, Ross, almost everybody from the Curse cast brought back to work their

magic on the old classics. Which they did — and whoops, overnight the

fortunes of Curse were reversed,

what with Alexandra Boyd, for instance, given so many more chances to shine with the beautiful dialog in Secret Of Monkey Island, and with Earl

Boen sounding so much more creepy and threatening in LeChuck’s Revenge. (For the record, I’m pretty

sure that LeChuck’s "’Twas no mere nightmare, Guybrush! Search your

feelings, you know it to be true!" line in the final act of Curse was inserted there only as a

special treat for Earl, to console him for not having been able to deliver it

in its proper context at the end of

LeChuck’s Revenge, because it makes

no sense whatsoever in the general context of Curse. Once Earl finally got to say it thirteen years later in

its rightful context — the scene where Guybrush and LeChuck come together as

brothers — one might just as well cut it out of Curse to avoid unnecessary superfluousness). That said, if we still

agree to make a mental effort and party like it’s 1997 (I’m game), there is

no question that the voice cast is the #1 attractive factor about the game

(#2 being the graphics, and #3 being the ability to rewrite Shakespeare in a

formally infinite number of ways). Whenever I’m playing it, the earnest and

exciting work put in by all these people easily makes me forget about the

lack of interesting ideas or general vision — in the same way, I suppose, as

watching all the magnificent Shakespearean actors in the Harry Potter movies whisks away your attention from how bad the

movies really are. Truly an A++ for the effort here. |

||||

|

Interface In terms of game mechanics,

Curse added relatively little to

the LucasArts legacy, since its interface was borrowed almost completely from

Tim Schafer’s Full Throttle. It

did, of course, mark a complete departure from the old Monkey Island interface — gone forever was the verb menu at the

bottom of the screen, marking a complete and utter transition to the

point-and-click mechanics. The action now fills up the entire screen, and you

can click on specific hotspotted objects or people to open up a coin-shaped

mini-menu, which lets you look, interact with inanimate objects, or talk to

animated characters. (Yes, these are all

of your options; in the mid-1990s, Sierra and LucasArts really went on a limb

competing with each other as to who could come up with a more laconic

interface on the largest number of their games). The same actions are also

applicable to objects in your inventory, which you open in a separate window

to mess around with. Unfortunately, this does

not eliminate the issue of pixel-hunting, which sometimes gets really

annoying, especially with the artists’ obsessive desire to clutter the screen

with as much junk as possible (case in point — the hold of LeChuck’s ship at

the beginning of the game; it is not difficult to find what you really need in there, but if you wish

to explore all the objects to see how many jokes have been attached to them,

you will need to be exquisitely agile with the mouse). Actually, the worst

cases of pixel hunting are on the mini-maps for Plunder and Blood Island: a

few of the locations that you can click to explore are rather inconspicuous,

so be sure to navigate your cursor meticulously over all the map areas at the

first opportunity, or else you might find yourself stupidly stuck just

because you forgot to check where to possibly go. The dialog system has

remained largely unchanged, as some of the options on the tree remain

mutually exclusive, prompting you to replay the game in order to squeeze out

all the hilariousness, while others can be explored one after another (I do

wish they had a system in place that let you separate the first group from

the second, but I guess it’s not that

important, after all, since this is not an RPG and your choices hardly ever

matter). Of note is the feature of timed

dialog, which was actually already present in the older games, but was not as

memorable because they did not have real sound — I am specifically talking of

the above-mentioned pirate song, which is kind of badly written by itself,

but can be cleverly interrupted at specific points if Guybrush wants to

insert a rhyme (to play along) or a non-rhyme (to disrupt the song); even the

music system is tailored in such a way that the song will change melodically

depending on the exact moment where you perform your intervention. This is

really nicely and smoothly done. But it’s just at one point in the game. I am not entirely sure

about the Options menu in the original version; mine, run through SCUMMVM,

only opens up the latter’s menu, where you can tamper with sound volume and

subtitles, but little else. If there was anything juicy out there, like a

boss key or something, it is gone forever with the advent of modern PC

architecture. Should that be important, though? It probably shouldn’t. As far as overall gameplay

is concerned, the game seems to be running smoothly, even on the SCUMMVM

emulator. You cannot die (well, actually, you CAN and WILL die, more than

once, but death in Monkey Island has

been effectively turned into as much of a source for hilariousness as

everything else), you cannot (technically) get stuck, and you can, if you so

desire, fall upon a whole variety of Easter Eggs, which, by 1997, the

terminally bored LucasArts staff had begun including in droves. There are

deeply hidden references to other Monkey

Island games, The Dig, and,

naturally, Star Wars (apparently there’s even a way to get lightsaber sounds

during Insult Sword Fighting, though I have not bothered to check it out last

time I revisited the game). It’s all nice to have — but, of course, none of

it is enough to change anybody’s general perspective on the game, let alone

mine. |

||||

|

If ever I gave the impression that I hated this game or anything, now is the time to reverse it. I

really enjoyed the game while actually playing it — the brilliant voice

acting, the nice graphics, the tricky puzzles, the occasionally funny jokes

kept me busy and entertained most of

the time (except, probably, for the entire "Three Sheets To The

Wind" act with its tedious recurrence of Insult Sword Fighting and

equally tedious cannon mini-management game, much more fun in concept than in

execution). It is mainly the bitter aftertaste that sucks — the feeling that

your experience has been somehow empty, or, at least, bland and shallow. The

same kind of experience that one probably gets when tricked into buying a

false diamond instead of a real one, even though you know that most people won’t be able to tell the difference

anyway. Monkey Island

does indeed have a curse — its original vision was so good that not only

LucasArts, but even the spiritual (and, partially, legal) inheritor of the

studio, TellTale Games, felt obliged to return to it time and time again.

Alas, sequels in video game franchises rarely work well if they do not follow

that original vision — at best, like Curse,

they can pass all the formalities and work for a while simply on the strength

of their technical innovations. But time puts everything in its right place,

and in the case of Curse, if there

is a better example of table-turning in the video game industry somewhere, I

have yet to see it. Those few modern gamers with a penchant for going back

into the past will most likely want to check the games out chronologically —

and unless they are bona fide retro nuts, they will probably pick the

remastered first two games over the mute, pixelated, and poorly running

originals. Only then will they

arrive at Curse, and now that it

has been stripped of its formal advantages (worse graphics, less

interesting voice acting for some of the key characters), I fail to see how

anybody could regard it as a truly worthy, 100% satisfactory sequel. I might even commit the ultimate sin in the eyes of the loyal fan and

state that there is no principal distinction in quality between Curse and the nearly-universally

lambasted sequel, Escape From Monkey

Island (other than the truly miserable 3D graphics of the latter):

although they were both designed by different LucasArts employees, both distort

the original Gilbert-vision in more or less the same way, and both have a

relatively similar ratio of fresh-to-rotten ideas. The difference, of course,

is that while Curse pretended that

it was taking its cues from the first two games (when in reality it wasn’t), Escape did not even have to pretend

that it closely followed the model of Curse.

But as it turns out, differences between secondary and tertiary product are

nowhere near as insufferable as those between secondary and primary... Still, on the positive side, if you agree to lower your expectations

and go along with the flow, LucasArts, TellTale Games, and Dominic Armato may

have done a good job of letting Guybrush Threepwood fade away semi-gracefully

rather than burn out in two short years, and if that is any consolation for the

fans, so be it. And if they ever decide to remaster the game, I’ll sure as

hell be replaying it — hey, it’s the least I can do to honor the memory of

the late great Kay E. Kuter. |

||||