|

|

||||

|

Studio: |

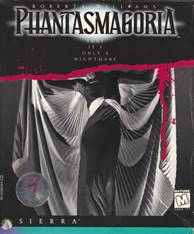

Sierra

On-Line |

|||

|

Designer(s): |

Roberta

Williams |

|||

|

Part of series: |

Phantasmagoria |

|||

|

Release: |

August 24, 1995 |

|||

|

Main credits: |

Director: Peter Maris Music: Jay Usher; Mark Seibert |

|||

|

Useful links: |

Complete

playthrough (6 parts, 320 mins.) |

|||

|

Roberta Williams’ Phantasmagoria was hardly the first FMV

(full motion video) game to be released on the market — the format, in its

classic form, had been activated at least three years earlier, with titles

such as Night Trap and The 7th Guest — but it arguably

remains the most famous, or, rather, the most infamous representative of this dead-end genre. This is in a big

part due to the arch-heavy promotion arranged for the game by Ken Williams:

as the legitimately next in a series of innovative projects led by his wife

Roberta, Phantasmagoria received

the VIP treatment from Sierra On-Line back when Sierra On-Line was at the

height of its artistic, critical, and commercial fortunes. In 1993, Gabriel Knight: Sins Of The Fathers

successfully advertised itself as the herald of a new age in computer gaming

(if not in the art world in general); one year later, King’s Quest VII showed the world that a computer game could be

(almost) as beautiful as a Dysney movie; and with Phantasmagoria, Sierra’s plan was to demonstrate that a computer

game could easily compete with a movie, period. That the FMV format would be tested out

on a horror game was pretty much predetermined — Roberta Williams had wanted

to do a bona fide horror game for years (her Laura Bow series had tiny elements of horror throughout, but was

still essentially in the detective mystery genre), however, she felt that

digital animation was an insufficient medium for a convincing horror

experience and that only live actors could make the player truly empathize

with whatever was going on. Now that graphic resolution, video editing

software, and optical disk storage capacity were more or less up to par, she

launched herself into the project with verve, without even realising all the

innumerable technical difficulties that would still go along with it. It has

been written plenty of times about how quickly Sierra ran out of budget, how

chaotic and painful was the entire process of filming and editing the game

sequences, and how, despite all odds, the game still managed to be

profitable, ultimately becoming Sierra’s best-selling title, though quite far

from critically best-received. The very fact that even the respective

Wikipedia article, put together from dozens of sources, remains one of the

longest articles on a Sierra game, shows just how definitively Phantasmagoria has passed into legend:

good or bad, it remains a one-of-a-kind watermark of human achievement in the

sphere of merging together the digital game and the video movie media. Contrary to the impression one might

get from reading certain retrospective descriptions, initial reception of Phantasmagoria was not overtly

negative — the whole thing radiated different!

so starkly that even those critics who were, from the very start, offended by

the silly plot, bad acting, lack of taste, and clumsy gameplay, had to admit

that there was still something special about the game; and there were even

those so taken by that something special that they did not even notice the

silly plot, bad acting, etcetera. But as time went by and the FMV experience

learned to overcome some of its original problems (e.g. in Sierra’s own Gabriel Knight: The Beast Within), and

then as more time went by and the FMV experience withered and died in the

face of the 3D graphic revolution, the novelty wonder of Phantasmagoria quickly wore off, and the game eventually saw

itself humiliatingly relegated to lists of «Worst Ever» titles, or, perhaps

even worse, to the wobbly area of Campy Guilty Pleasure. At least in those

early days, to play the game you had to extract it from its imposing seven-CD package (a record of sorts),

one look at which already implied a certain reverence. But with the digital

download epoch upon us, and in an era in which a 2Gb-weighing game is looked

upon as a pitiful indie project, nothing remains of that reverence, and these

days, people who still launch Phantasmagoria,

or people who agree to kill some time to watch a YouTube playthrough, go into

it expecting nothing but a bit of giggly, campy fun — and come out of it

fully satisfied. This is not quite right, in my opinion.

One thing that Phantasmagoria was

never intended to be, and one thing that it is definitely not, is «funny» (well, anything,

including King Lear and Schindler’s List, can be «funny» if

you wire your brain in certain ways prior to the experience, but that really

says more about yourself than these works). Stupid, unbelievable, clumsy,

even insulting to one’s intelligence — but on a gut level, the game actually

works, and in this review, I shall try to show why it does. Many people writing

their own reviews of Phantasmagoria

see it necessary to confirm the «guilty pleasure» status, with formulae such

as «yes, of course it’s an awful game for many reasons, but...». Well — correction: there are many things that are awful about Phantasmagoria,

but even when all of them are put together, they still do not make it an

awful game. As far as I’m concerned, even today, when played in the right

state of mind, Phantasmagoria on

the whole succeeds in its original and primary purpose; it is only when you

let your mind overthink the issue and take charge over your emotions — not

really a very good strategy for experiencing an art piece — that you begin to

feel ashamed for enjoying it. And it is precisely this paradoxical situation

— how could a game that is objectively «bad» on so many levels still get it

«right» on the whole? — that makes Phantasmagoria

a relatively unique title, if not in the entire history of video gaming, then

at least in the history of Sierra On-Line, or maybe adventure gaming as a whole.

So let us explore this a little more closely. |

||||

|

Content evaluation |

||||

|

It would hardly be an

exaggeration to state that Roberta Williams, a woman of exceptional stamina and

audacity when it came to designing and producing video games, was never

exactly what you’d call a «master storyteller». Her scenarios for King’s Quest and Laura Bow were usually a melange of well-explored motives from

fairy tales, myths, mystery stories, and various literary pulp, whose chief

attraction was her ability to turn them into a variegated, but logically

connected system of puzzles for us to solve. Whenever she paired up with a

more imaginative partner, the improved results were immediately noticeable

(as in King’s Quest VI, bearing the

writer’s seal of Jane Jensen); however, for Phantasmagoria her sole writing partner was Andy Hoyos, a Sierra

veteran who had previously worked exclusively on graphic art for the games

and would never again be credited as «writer» for the studio — suspicious,

no? Hardly surprising, then, that the

principal plot of Phantasmagoria

will take approximately five seconds to be chopped up into a small bunch of

bearded tropes by connoisseurs of the horror genre from its roots in medieval

fantasy stories to the Gothic novel and more recent transformations in

Hollywood movies all the way up to The

Shining (there are so many direct parallels between Kubrick and this

game, I was almost befuddled to find that Roberta had, after all, resisted

the temptation to have the heroine’s mad husband chase her around with an

axe, shouting HERE’S DONNY!). Man

and wife move into a luxurious, abandoned, supposedly haunted mansion — wife

inadvertently stumbles into a secret room and discovers a terrible secret —

man is driven insane by the same evil spirit that formerly possessed the

mansion’s previous owner — wife has to save the world by driving the spirit

back, at the cost of sacrificing the husband. You’ve heard / seen / read it

all before, right? None of this, within the context of an

adventure game, is necessarily bad by itself. However, compared to all of her

previous games, Roberta commits precisely one

fatal mistake — almost a crime, in

fact, that one single thing which doomed the game from the start. Having

designed a story that is essentially «pre-modern» in nature, a tale that owes

its motivations, details, and morals more to the tales of Charles Perrault

and the novels of Ann Radcliffe than to Stephen King or Wes Craven, she

decided to set the action in the present time, rather than a fictionalized

version of the 17th or 18th century, where it so very obviously belonged. I

can only hope that she did this not because she actually thought «hey, this

could work» (most of the time, Roberta comes across as a very intelligent and

perceptive person), but rather because it would have been much more difficult

and expensive to model a pre-Industrial Age setting for an FMV production. Even so, to understand in this

situation is easier than to forgive. At the very start of the game, we are

supposed to suspend disbelief at the idea that somewhere on a small island

off the coast of good old New England, a practicing magician in the late 19th

century had built himself a huge Gothic mansion (not forgetting a separate

family crypt linked to the house by a complex system of vaulted underground

passages!); that upon his passing, the mansion had remained unoccupied for

almost 100 years in almost exactly the same state that his master had left it

in (though, apparently, somebody did take good care of the dusting and took

the time to install modern infrastructure); and that, somehow, a couple

consisting of an ambitious photographer and his writer wife, who had just

published her first bestseller, could — and would — afford to move into this mansion, because there is

nothing a successful young writer dreams of more than to move into a huge

Gothic residence in the middle of nowhere in order to find peace, quiet, and

inspiration for her new novel. This initial premise is already so

delirious (in my own gaming experience, the only thing that rivals it in

whackiness is the universe of Resident

Evil) that even if some of these things were eventually to be justified

within the game, it would be much too late. It is perhaps best that they are

not, and neither are all the gaping plot holes, inconsistencies, and

illogical actions of the game’s protagonists that I won’t even bother

listing, because all of them have been laughed off dozens, if not hundreds,

of times in various accounts of the game. At times, it feels as if, perhaps,

Roberta was intentionally mocking

her audience — I mean, for God’s sake, the name of the magician who used to

own the mansion is (drumroll!) Zoltan

Carnovasch, which, admittedly, is a little better than something like

"Ferdinand Al-Rasputin", but not by much. I suppose that

"Zoltan" implies a Hungarian origin for our bad guy, but

"Carnovasch" is an impassable impediment — my best guess is the

Greek surname Karnavas, slightly

misspelt and Germanized, ultimately chosen for proximity to the word carnival. Of course, all bad guys

ultimately immigrate to the coast of New England from an amalgamated Eastern

Europe, the land of Dracula, Slobodan Milošević, and crazyass

orthographies. But even most of these guys usually think twice before

introducing themselves as Zoltan

Carnovasch to the stupefied authorities on Staten Island. The game’s protagonist, who herself

goes by the no-slouch name of Adrienne Delaney, through pretty much all of the game behaves exactly the

way we’d expect a heroine of an old-fashioned Gothic novel to behave —

amazed, confused, terrified, but brave and determined enough to go it alone,

since she is probably stranded in some lonely castle from which there is no escape

anyway. Except that for Adrienne, all roads are open: you can even visit the

nearby cute little town of «Nipawomsett» (is that supposed to sound

Algonquian?), where some of the locals will be happy to share their concerns

about the Carnovasch Estate with our heroine, but that will be pretty much

it, since, apparently, Nipawomsett has long since defunded its police and the

only local protection is offered by vicious guard dogs. And Adrienne has a

cat. As far as the basic laws of organizing

a bona fide horror story are concerned, the game evolves reliably and

predictably. Action is split into seven chapters (each corresponding to its

own CD), with each next chapter gradually gaining in intensity. First comes

exposition and exploration, with only faint premonitions of danger. At the

end of Act 1, the jack-in-the-box comes loose, and you begin to observe the

personality changes in Adrienne’s husband, Don, who gradually mutates into an

asshole, then a psychopath, then a rapist and alcoholic, and finally a crazy

cackling murderer. At the same time, Adrienne gradually opens up new and new

hitherto hidden areas in the mansion, learning about Zoltan’s history —

apparently, the man really was a 19th century Bluebeard, killing off all his

wives before they even had a chance to record a proper breakup album.

Finally, just as she learns of a proper way to send the evil spirit

possessing her husband back to Hell, the husband decides to follow in the

footsteps of Carno... and at this point, the game turns into something

completely else. I realize that few things in the

universe could have been able to elevate such a plot to any sort of

respectable position. But even in such a dire situation, something could be done — at the very least, by means of quality

dialog that could patch up some of the most blatant holes and illogical

phenomena, as well as make the characters into approximate equivalents of

real human beings. Unfortunately, most of the time the dialog in the game

feels as if they’d hired a 10-year old with a total deficit of social skills

and zero book reading experience. A minor example from a sequence in which

Adrienne, angry about finding some locked doors in the house, confronts her

realtor in Nipawomsett: Adrienne: Are you sure you gave my husband all

the keys to the Carnovasch Estate? There seem to be some locked doors. Realtor: I gave him all I had. But if you don’t

believe me, why don’t you just check for yourself? Adrienne: Well, I think I will. (Checks the files, finds a large key in one

of them.) Ah-ha! Carnovasch Estate. All the keys are... what’s this? Realtor (examines

the key attentively): It’s a very large key. Adrienne: (Stares

with condescension). Realtor (throwing

up his hands): So sue me! Adrienne: (Eats,

shoots, and leaves). This is certainly not a principal

sequence or anything, but I quoted it specifically to illustrate the, uh,

«magic realism» of the characters’ behavior in the game. And this is before we even get around to spending

time with two of its most obnoxious heroes — the clairvoyant homeless lady

and her retarded overgrown son, both of whom Adrienne encounters on the

premises of the estate and immediately proceeds to hire as house help

because, honestly, who wouldn’t

hire a couple of batshit crazy homeless dudes who just happened to spend the

night in your barn? Not only is it progressive, but now, in the immortal

words of Allen Toussaint, you also get your fortune told for free. Thrown

into the game as comic relief, Violet and Cyrus goof around for a while,

spoiling the reputation of homeless people all over the globe, before

eventually meeting their fate at the hands of a completely deranged Don later

in the game (provided you take the extended ending and run around long enough

to actually discover both of their corpses). «Retro-dialog» between Carno, his

wives, and their lovers, mostly shown to Adrienne in psychedelic visions

through various mirrors in the houses, is even cornier, coming in short,

trite, children’s primer phrases ("Zoltan! I love only you, you must

believe me!" – "I want to believe you, grumble grumble") that

would have horrified Victorian pulp writers. It is, in fact, so bad that I

have a hard time believing all of this was not intentional — that Roberta and

Andy did not specifically exclude all marks of literary prowess from their

characters’ speeches, so that the player would only focus on the atmospheric

dynamics of the game, in the same way that, for instance, Robert Bresson

famously prohibited all of his actors from «acting», striving to strip his

movies of the faintest signs of artificial exaggeration. But no, Roberta

Williams is not Robert Bresson, and I do not have any justification to

suspect some sort of extra artistic «anti-depth» in her script. Indeed, were Phantasmagoria to be judged on the strength of its story and

dialog alone, it would unquestionably have to be rated as the worst Sierra

On-Line game of all time, and a serious contender for the Top 10 Worst

Plot-Based Games ever made. Its saving grace is, however, that its plot as

such does not matter — or, rather, it only matters inasmuch as it is a

clumsy, grotesquely deformed skeleton upon whose bones Roberta paints her

disturbing, unsettling spectacle. The comforting thing about it is that the

game does a pretty good job of automatically shutting down your brain at all

the right moments, rather than waiting for you to take the initiative

yourself. |

||||

|

In her early years, Roberta

Williams was a fairly solid puzzle designer — the challenges she set out

before the player could hardly qualify as «uniquely brilliant», but King’s Quest and Laura Bow always delivered the goods. With Phantasmagoria, it is clear that Roberta’s priorities had

undergone a serious shift. First and foremost, this game was supposed to hit

you in the feels — and getting hit in the feels, real hard, does not go along

all that well with putting pressure on your brain cells. One minute you’re

witnessing a gruesome vision of a uniquely horrific murder, and then the next

moment you have to go and figure out the correct procedure for opening a

locked door? sounds pretty anti-climactic, doesn’t it? Even more importantly, the

FMV format brought some obvious limitations to the classic procedure of

point-and-click gaming. According to Roberta’s plan, each and every action

taken by the player had to be reflected cinematically — picking up stuff,

using stuff on stuff, even unsuccessfully

using stuff on stuff. Before FMV, you could very easily animate tons of extra

actions, including those that did not lead to any useful results; at the very

least, you could slap on a text window stating "no, you cannot insert

the mayonnaise sandwich into the electric socket, and you’d be sorry if you

could" and get away with that. But now that a new, fully cinematic age of

adventure gaming was supposed to be dawning upon us, it turned out that (a)

it would take too much pressure on

the actors and the filming team to take multiple blue-screen takes of all

this extra action, and (b) it would have probably taken not seven, but

seventy-seven CDs to carry it all — and the video sequences already had to be

horrendously compressed as they were. Later on, Jane Jensen, who

faced the exact same problem for Gabriel

Knight: The Beast Within, would find a compromising way to work around it

— in her game, many onscreen hotspots could at least be clicked on just to

get a verbal description or reaction from the lead character, without any

additional cinematography involved. But apparently, Roberta would not have

it. In Phantasmagoria, something

actually happens each and every time you click on a hotspot — even if it is

just to look upon a portrait hanging on the wall, Adrienne will be shown

walking up to it and staring at the picture. If you click on a sofa, the

heroine will walk up to it, slowly set her butt on its surface, fidget around

for 5-6 seconds, then just as slowly stand up and walk away — accomplishing

absolutely nothing, but giving you, the player, a tiny illusion of absolute

control over the blasted environment. This is one feature of the game that

probably looked overwhelming at the time, but now just looks stupid. Who

wants to kill 20 seconds of one’s precious life watching an FMV sprite sit

down on a sofa and stand up from it? (Unless, of course, you find something

Zen-like about the whole thing). There are dozens of such moments all over

the game — which is even more ridiculous considering they could have spent

this part of the budget on something much more meaningful. Like designing an actual

puzzle, for a change. The biggest difficulty you are going to encounter in

this game is finding all the right hotspots and direction arrows, desperately

waving your talisman-shaped cursor around the screen to see it change from

piss-yellow to blood-red. Once you know where all the goodies are located,

grabbing stuff and using it on other stuff is trivial work. Pick up a tool to

open a trapdoor. Grab hold of a soup bone to distract an impeding animal. Use

the old newspaper-on-the-floor trick to get a much needed key. (I’m listing

all this spoiler stuff just because it is all but impossible to «spoil» any

brainy challenge in this game, since there are next to none). And if all of

that still somehow happens to be challenging for you, cheer up — there is a

huge friendly red skull at the bottom of the screen, clicking on which will

always result in its telling you, in an appropriately doom-laden voice, what

exactly you should be doing next. I wish I had me a skull like that at home. That said, in all honesty, the chief

goal of Phantasmagoria is not to

just make you beat the game, but to provide you with the Complete

Phantasmagoric Experience — and that, admittedly, is just a tad harder. A lot

of the sequences, including some of the most chillingly famous, are optional:

as time goes by, things change about the Carnovasch Mansion, and in order to

catch them all, you have to explore all of its locations over and over again,

which is tricky, because some actions will automatically result in the

current chapter being completed, and some or all of its optional events gone

for good. And since, in an almost unique turn of events for Sierra, Phantasmagoria does not feature a

point system, you won’t even have a vague idea of how much juicy action you

might have missed upon completing the game. And no friendly red skull is

going to give you any advice on this

part, which is too damn bad, since it is actually the best part of them all. As far as actual user-friendly design

is concerned, though, I don’t think the game has any significant flaws. Maybe

just one: at one point in the game, in order to achieve progress you have to

closely examine one of your picked-up objects in order to turn it into

something different. That can actually be a stumble, since the «Examine

object» option in the menu is not immediately presented as something

particularly useful (you just get a nice little 3D close-up of the gadget),

and this is the only point in the game when you are supposed to find out that

it has a vital practical application as well. (I suppose you can be made

aware of this if you consent to carefully reading the manual before playing,

but who in the world reads game manuals? this is a frickin’ adventure game,

not an IKEA challenge!) In the Adventure Game Logic department,

the game does not commit too many crimes — most of the crimes lay with the

actual plot, rather than with player-dependent ways to advance it — although

it does look as if every once in a while, puzzles look the way they do simply

because somebody did not have the time, money, and energy to make them look a

bit more believable or challenging. For instance, at one point you need to

repair a telescope by inserting a missing lens — which you should probably be

able to buy in some store in Nipawomsett or at least uncover in some dark

corner of some dark attic in the house; in reality, the missing lens will be

found sparkling at your feet on the sandy beach, approximately 20 or so

meters away from the telescope itself, and all you have to do is pick it up

and use it on the telescope. Thus, this is essentially a non-puzzle that (a)

adds virtually nothing to the gaming experience and (b) makes no sense from a

realistic point of view. Why is it there at all? Beats me. Maybe Roberta

Williams has a secret thing for girls inserting shiny objects in little

holes. (Sorry). At the very least, for the first six

chapters in the game you set your own pace for all this pseudo-puzzle

solving. Things change drastically with the last chapter, when you are thrown

into a race against time and forced to take action quickly and decisively, or

face the gory (very gory)

consequences. This sequence — a two-part chase through both formerly explored

and completely new parts of the Estate — has frequently been lauded as the

high point of the game, and while this extra praise sells the rest of the

experience a little short, I do have to admit that it’s pretty damn well

designed. You shall probably die a lot, but the game immediately reverts to

the last cut-off point when you do; and although the sequence as such is not

long, they really went out of their way to include a lot of filmed dead-ends,

often trapping you into thinking that you are doing something right when in

reality you are not. The tension really helps out here, even if the actual

puzzles remain just as simplistic as they were. Which, in turn, brings us to

the most important, if not the only

important, selling point of the game: THE FEELS. |

||||

|

When it comes to B-movie

level experience, the important thing is, of course, not whether the plot makes

any sense or if the script writers managed to come up with some truly

original and unpredictable ideas; the only thing that matters is whether the

movie fails or succeeds at capturing your attention and making you care about

what is going on. (In a way, you could actually argue that this is not that

much different for A-level movies as well, or any work of art in general). And if certain things are done just

right — the acting, the camera work, the editing, the little individual

touches — it is, at the very least, theoretically possible to make one care

even about a character who goes by the name of Zoltan Carnovasch. Theoretically. If Phantasmagoria were an actual movie, I seriously doubt that it

would have ever attained that level of quality. But Roberta Williams was not

making a movie; she was fleshing out a chunk of virtual reality, where player

involvement and agency take the place of certain cinematographic aspects, and

this particular relationship between screen and conscience was handled by her

just right — at least, I know for sure that it can work right, since it legitimately worked on me. The main character of Phantasmagoria is not really Adrienne

Delaney, empathizing with whom is pretty much impossible due to the inane

script and generally bland acting (on which see below). Nor is it the ominous

Mr. Carno, who makes himself visible every once in a while but is given no

time at all to demonstrate any character development. The main character is,

of course, the Mansion itself — a large, twisted, opulent, and fairly

unpredictable entity which, fairly quickly, begins to shift and transform

before your very eyes, to the point that eventually you might get a little

pang of fear before checking into a room that you have only just visited in

the previous chapter. At least at the very

outset, with things still relatively normal, you have Don, the photographer

husband, working his ass off in the extra lavatory which he plans to turn

into a dark room, and you can always run to him for company and comfort. By

the beginning of the second chapter, Don has locked himself inside the dark

room for good, and you are left to rummage around the place all by yourself —

a lonesome and confused presence inside a huge and mysterious house which

seems to have a life, and an evil agenda, of its own. Everything is rigged to

that effect: the backdrops, the lighting, the creepy music accompanying you

throughout, the ghostly ambient sounds. Each time I needed or wanted to

emerge from the claustrophobic confines of the Mansion into the open air, I

remember inadvertently making a small sigh of relief — and note, no zombies!

It is not the easiest thing in the world to get a classic Resident Evil vibe going with actual

evil only being implied, rather than witnessed, most of the time, but Roberta

and her directors did a good job. Looking at all these

developments in their general cultural context is not particularly

interesting. Echoes in the hall, visions in mirrors, a disappearing necklace,

a grim mechanical fortune-telling automaton, a movie projector or a

grammophone record starting up on its own — we all know that from countless

horror art pieces. What is interesting is that some of these, at least, can

make you jump, and others will want

you to rush out of that mansion, get in your car, and drive straight out to

the small and peaceful village of Nipawomsett, so as to soothe your nerves a

bit in the local friendly general goods store, whose owner is chilling out to

the instrumental sounds of ‘Cell Block Love’ from Leisure Suit Larry VI (one of the few self-referential Easter

Eggs in the game). Unfortunately, given how little there is to do in the

town, and how unresponsive the local population is, you will have to go back sooner rather than later. The game arguably reaches

its atmospheric peak in Chapter Five, the one and only time when action

switches from daytime to nighttime — at that point, even being outside brings

no relief whatsoever, and the whole place seemes besieged with spooky

nightmares to destroy your sleep process on that particular night. This is

when the mirrors, scattered around the house, lock into Bluebeard mode and

begin showing you the juicy, gory, and, might I say, fairly inventive (for

once) ways in which the nice owner of the house used to murder his wives —

the very bits that triggered most of the controversy around the game, leading

it to be banned and castigated around the globe. Are these sequences

«tasteless», just a gratuitous show of violence to titillate the darker brain

areas of the game’s (predominantly male, as usual) audience? That is

certainly a possible way of looking at it. But a more natural way, in my

opinion, is to see them simply as the culmination of a slowly and efficiently

increased feeling of existential dread, which had started accumulating

already at the beginning of the first chapter. You can play the hardened

nihilist and laugh these scenes off the same way we laugh off a Mortal Kombat fatality, but even then,

deep inside you will know you are most likely doing this just to shake off that

feeling of dread. These sequences are not there for laughs — and certainly

not for the faint of heart and/or stomach, either. Then, at the beginning of

Chapter Four, there is the equally infamous «rape scene», another source of

major controversy BECAUSE RAPE RAPE RAPE — though, technically, the scene

begins as a fairly innocent and consensual lovemaking scene between Adrienne

and Don, in which the latter is seemingly trying to «atone» for his bad

behavior in the previous chapters, before becoming re-possessed by his demon

and turning to much more rough action. Poorly acted as it is, I think that

the scene tickled people’s nerves not so much because of the forceful action

itself, but largely because it was you,

the player, who was being forced on the screen. Like it or not, by the end of

the third chapter you and Adrienne Delaney, to a certain degree, have become

one, and, let’s be honest, who really wants to be forcefully penetrated in

one’s bathroom by an ugly-looking dude with a ponytail, so busy making

retarded demonic faces that he even forgets to properly pull down his

boxers?... okay, sorry, I think I’m making this feel less horrific than it

should. In reality, the event does mark a turning point in the game, after

which the dread begins to accumulate at an accelerated pace, rarely letting

go until the explosive finale. Not even the ill-fated

comic relief, coming in the form of such poorly conceived characters as the

cartoonishly sleazy realtor in Nipawomsett and the disastrous duo of Violet

and Cyrus, can spoil the mood. I distinctly remember, for instance, actually

being relieved upon visiting Violet’s stupid, cringey «seance» in Chapter

Five, simply because it felt like a relatively safe space, in the company of

dorky, but much needed friends, where you could shake off the dreariness of

the nighttime Estate. The very fact that having company — any company — in this place gives you

a nice and warm feeling is a good sign that Roberta and Co. must have been

doing something right. Naturally, when it comes

down to the frenzied chase scenes of the last chapter, you won’t have much

time to spend on feeling claustrophobic and uncomfortable. This is a perfect

time to panic, given that no matter where you are, two or three seconds spent

in confusion doing nothing will imminently lead to capture and death — and

while, once again, it is extremely easy to laugh off Adrienne’s death

sequences when you’re on the outside looking in, it is quite a different

matter when you yourself are

Adrienne, and have been so for quite a period of time. The feeling of a

necessity to escape at all cost, to take improvised, quick, and risky action,

to aggressively defend your life against your own partner — all of this is

actually quite real, and in the heat of the matter you shall hardly have any

time to seriously evaluate just how unrealistic is Adrienne’s blue-screen

posturing in this context, or how corny Mad Don’s behavior is, or how they

were not able, after all, to realistically merge their computer-drawn Demon

with the filmed Adrienne in a single shot. At the very end of the

game, when in its final shots we see Adrienne walking away from the mansion

in a clearly catatonic state of mind, we finally get to become completely and

utterly one with the character — simply because that final act, when you play

it for the first time, is bound to leave you emotionally exhausted. Again,

would it have worked as a movie? For 1995, I cannot really see it. But as a

part of your own experience? I

still got much the same vibes when replaying the game recently, even if

nothing about it any longer came to me as a surprise, and the compressed old

video looked abysmal when played in full screen mode. Granted, this is all

due far more to the technical handling of the game than its script — which

means that this is a good moment to switch our attention to those trusty

«circumstantial» aspects which save it from ruin. |

||||

|

Technical features |

||||

|

Phantasmagoria was filmed in its entirety on the premises of Sierra’s own brand

new film studio in Oakhurst; Roberta and producer Mark Siebert were

responsible for the cast, while little-known B-movie director Peter Maris

took charge of the action. Since most of it was filmed against a blue screen,

this meant that actual backdrops still had to be rendered; this was the

responsibility of Andy Hoyos, and he did a pretty nifty job. There is no

freedom of movement to speak of — on each screen, Adrienne and the NPCs can

only move in strictly determined and highly limited patterns, random

wandering around is simply impossible for technical reasons — but within

those limits that are actually possible, the integration of live actors and

painted backgrounds is... well, obviously not seamless, but tolerable

even today (and it must have looked pretty amazing back in 1995; I myself did

not pick the game up until about six-seven years later, by which point FMV

was already dead and buried). The Mansion itself

represents a rather odd combination of styles — grotesque, Baba Yaga-ish gothic on the exterior, opulent Louis

XIV-fashion on the inside (particularly the grand hall and the bedrooms on

the second floor), with the Gothic elements pushed out to the periphery (e.g.

the family crypt, where Carno apparently willed for himself and his wives to be

buried in medieval king style). On the whole, it’s fairly close to the

parameters of the House of Usher as depicted in Roger Corman’s classic movie,

but rendered in much more detail, since you have the ability to explore the

entirety of the building. Meanwhile, the outside territory largely looks like

some weird desert island, with oddly shaped trees lining the territory —

ironically, not unlike the evil man-hating forest in Roberta’s King’s Quest IV, though these ones are

at least superficially harmless. Another thing that brings back to mind

Roberta’s early masterpiece is the day-to-night contrast, which makes the

craggy trees even spookier and the claustrophobic feel of the Mansion even

denser. Integration of live acting with CGI

effects is... okay, I guess. They succeed in making Adrienne’s infamous death

scenes look not just disgusting, but even somewhat realistic (at least if you

do not insist on rewatching them in slow motion to understand the mechanics),

and the final confrontation with the Demon seems more imposing to me than,

say, Gabriel Knight’s face-to-face confrontation with the Werewolf in The Beast Within — largely because

they avoid putting the Demon and Adrienne in the same frame and thus make

your brain accommodate each image on its own terms. Overall, if not for the

clearly visible ugly contour lines separating the blue-screened actors from

the handdrawn backdrops, I might be able to call the game an early

technological marvel, but, unfortunately, it does carry the specific stamp of

its time. And now it is time to say a few words

about one of the most questionable aspects of the game — the acting. It is usually stated as a

fairly inarguable point that the acting in the game is atrocious, but the

reality, I think, is a little more complicated than that. It is true that, in

their attempt to carry out the dream of integrating cinema and videogaming as

fully as possible, the Sierra people were unable to enlist any serious acting

talent — in a way, this is a step down even from the level of Gabriel Knight: Sins Of The Fathers,

but then (a) in Gabriel Knight,

actors only had to contribute their voices, running fairly small reputational

risks, and (b) Gabriel Knight had a

good script: I’m fairly sure that Roberta and Mark Seibert could not even

begin to entertain the idea to lure in anybody big with this kind of drivel.

They did, however, enlist professionals — Peter Maris, who directed the

filming, had been in the business since the 1970s, and all the actors were

actual actors (at the time, at least: I’m pretty sure most of them have long

since shifted to other jobs). Relatively little of the acting is what

I’d openly call bad, or, at least,

not everything that is bad about it is specifically due to the actors

themselves. Too often, the poor guys simply fell victim to the deficiencies

of the script (you try saying

"Fine, I’ll go to the store and get you your goddamn drain

cleaner!" with a straight face), or to the uncomfortable conditions of

working against a blue screen; I seriously doubt that if they’d gotten Nicole

Kidman and Tom Cruise to play the principal roles, this would have made the

game an equivalent of Eyes Wide Shut.

There are occasional moments here and there showing that both Victoria Morsell,

who plays Adrienne, and David Homb, playing Don, can be convincing, but there

are also way too moments showing Victoria / Adrienne rather at a loss about

what to do, and David / Don has a serious tendency to overact (particularly

when getting into his "mad Don" image — oh my God, that

laughter...). Unfortunately, the only truly serious acting talent that they

got, the British classical actor Douglas Seale, gets exactly one scene in the

entire game — playing Carno’s adopted son Malcolm, now over 100 years of age,

who fills in the last pieces of information for Adrienne and gives her the

recipe for putting the Demon back in his place. They even accomodated him

with slightly less cringey dialog

than usual, making his appearance in the penultimate chapter into a high

point for the game. (Alas, Seale passed away in 1999, only living up to 86

years in the real, non-demonic world). Where would great videogames be in

this world, really, without bona fide Shakesperian actors moving to Hollywood

and spending the last parts of their lives acting in trashy movies?.. Alas, on the other side of the spectrum

you shall find the mysterious and horrendous V. Joy Lee, playing the role of

Harriet, the clairvoyant hobo in the red garden gnome cap. I have not been

able to locate any additional info on her (other than that she also had a bit

part to play in Phantasmagoria II)

— she does not have any other acting credits listed on IMDB, meaning that she

either came from some seedy theater circuit or, as a rare exception, was picked

from non-professionals. (Heck, for all I know she could have been an actual hobo, picked off the street for

authenticity’s sake). Now that is

bad acting with a flair, the proverbial kind that should be used for teaching

materials. Mind you, it is perfectly possible that V. Joy Lee, whoever she

is, saw things more clearly than anybody else on the team (she did play a

clairvoyant, after all) and was reveling in the corny dialog and overacting

like mad precisely because she,

unlike the other actors, regarded the whole thing as a campy, corny, comedic

enterprise from the start, refusing to take it seriously. Unfortunately, such

a scenario would probably be to good to be true. Anyway, regardless of what

it was really like, V. Joy Lee is the living banner of all those who are

unable to see Phantasmagoria as

anything other than a platter of first-rate cheese. Too many of the actors involved in the

game are simply impossible to comment upon because their parts are so tiny —

all of Carno’s wives, for instance, who are there only for a few seconds to

get gruesomely murdered. They put on as good a show as possible for those few

seconds, but it is hard to rate an actress if all she does is scream

(Leonora) or gurgle with a funnel inside her throat (Regina). Of course, the

shortness of these scenes was largely dictated by technical limitations: even

seven CDs could only hold that much

video, and even that had to be severely compressed. (Ken Williams, in his

autobiography, lamented that the original high quality footage had probably

not survived in the archives — otherwise, it might have been possible to

produce a remastered, or even expanded, version of the game). The biggest loss is probably a certain

amount of scenes that Roberta was planning to include at the beginning of the

game, featuring Adrienne and Don together in the pre-transformation period.

Indeed, we get to see very little of the loving husband and wife interaction

— other than a tiny lovemaking scene in the intro (the one where they

originally planned to show some nudity, but ended up with just a bit of

sideboob) and a morning conversation at the kitchen table, Don spends the

first day getting busy in the dark room, and then it’s already too late. This

way, we do not get to care much about his character — and are forced to treat

him as just a corny, cackling villain. It could have gone much better than

that. Still, when all is said and done, I

reiterate that acting (or lack thereof) is hardly the worst problem in this

game. With a solid script, all those guys might have been able to pull their

weight (all except V. Joy Lee — but I suppose that a truly solid script would

simply leave no place for her character anyway). |

||||

|

One aspect of the game that genuinely deserves

an A+ is its soundtrack, credited to Sierra veteran Mark Seibert (who also

produced the game) and newcomer Jay Usher. The strategy here for the main

bulk of the game was to leave the outdoor sequences largely music-less,

adorned with nothing but quietly soothing nature sounds; however, as soon as

you set foot inside the Mansion, all sorts of soft, mechanical, creepy

music-box-style melodies begin to emerge, relentlessly working an unnerving

effect on your conscience. Isolated keyboards, strings, bits of bassoons,

percussion, chimes, snippets of ominous melodies, all working toward creating

a tense, paranoid atmosphere where you constantly expect something to jump

you out of some dark corner. This

sonic ambience is not as pronouncedly «deep and dark» as the one in Phantasmagoria 2, for instance, with

the choice of instruments and tones more reflective of Roberta’s King’s Quest style — more fantasy

fairy-tale-ish than the cyberpunk / sci-fi style of the next game in the

series; but it somehow manages to be nearly as disturbing. Since most of the game is centered

around Adrienne exploring the Mansion, it is natural that this Mansion

Ambience is the one piece of sonic tapestry that is going to stick around in

your memory for the longest time — but, admittedly, there are not that many

fleshed-out musical themes outside of it. In fact, the only fleshed-out musical composition outside of it (various

repercussions of which are constantly heard in cutscenes) is the

mini-oratorio, ‘Consumite Furore’, that Mark Seibert wrote for the game,

replete with a solemn Latin libretto and a neo-Gregorian chant recorded by a

135-voice choir (!). It sounds predictably corny by itself, especially in

those spots where they begin marking the rhythm with the early 1990s style of

gated drums, but in the context of the game, especially when accompanying the

scenes with the Demon at the end, it is quite effective when it comes to

pumping your nervous system with dread-scented adrenaline. A special mention must be made of the

stock sound effects in the game, and I certainly do not mean the creaking of

chains, chirping of birds, or squeaking of doors — rather the bubbling,

gurgling sounds of bloody entrails pushed through a funnel into the throat of

one of Carno’s wives, or the slurpy, squishy sounds of Adrienne’s face mashed

into pulp by the surprisingly beefy arms of the allegedly immaterial Demon.

Some of those are almost delightfully disgusting, contributing even more than

the visuals to making you sick in the stomach — the visuals, with their lo-fi

quality and pitiful resolution, have become dated a long time ago, but the

sounds are immortal. (That said, trying to hit Don in the head with a hammer

does lead to the suspicion that the guy was really the Tin Man in disguise

all along). In short, I would say that the game’s

sonic ambience is a good pretext all by itself to play the game — given how

easy all of its puzzles are, you might just as well close your eyes and

simply enjoy its aural spirit, if you are annoyed by the poor quality of the

graphics and the bad acting. |

||||

|

Interface For all of its admirable

and dubious innovations, one thing that remained almost surprisingly

unchanged from the standard introduced with King’s Quest VII in 1994 is the gameplay mechanics. Well, maybe

not so surprisingly, considering that both games were supervised by Roberta

at the same time and that of all the people at Sierra, she had to follow her

own design rules, after all. Just like King’s

Quest VII, Phantasmagoria is

divided into separate chapters — in this case, each separate chapter

corresponding to the contents of a separate CD — and when you start a new

game, you can actually begin playing from the start of any of these chapters

(though you will have formally missed on all the optionally accessible

content of the previous ones, e.g. if you could optionally get some object in

Chapter 5, but begin playing at Chapter 6, you won’t have that object in your

inventory when you start the game up). You also cannot have multiple saves in

a single playthrough — instead, there is a floating bookmark which marks your

progress, which is just as annoying as it was in King’s Quest VII. The point-and-click

interface remains utterly minimalistic: you use the exact same cursor shape

to talk to people, look at objects that can be looked upon, and pick up /

operate upon objects that can be interacted with. The bottom of the screen is

wasted on a huge inventory window (which could have just as easily be

produced in a pop-up format), the already mentioned red skull providing

occasional hints (EXPLORATION IS KEY!),

and an eye icon which lets you magnify your inventory objects, juggle them

around in nice early 3D fashion, and once — only once, which is fairly frustrating — manipulate them in order

to achieve necessary progress. In terms of gameplay

mechanics, the biggest deficiency of Phantasmagoria

— of all FMV adventure games, in fact — is the inability to freely move your

character across the screen. With a little extra work, they might have

achieved this goal, but apparently, freedom of movement was seen as a

superfluous feature, because, let’s face it, what do you need it for? In classic animated games, you needed it to

walk closer to the person or object you needed to interact with (otherwise,

you’d always get the proverbial "You’re not close enough"

response), but if you could simply mouse-click the person or object in

question, with the game automatically setting up a rigid beeline trajectory

for your character, why would you even need to be able to move your character

into some random direction, without a specific purpose? Well, it actually turns out

that the lack of free movement hurts one major purpose of the game — immersion. For me at least, it is more

difficult to identify with the character I am playing if I am constantly

railroaded into a limited set of predetermined trajectories; it feels like a

conscious step back from the digitally animated stage of such video games,

and one more element of turning the «game» experience into an «interactive

movie» experience. Additionally, it actually makes it more difficult to

explore the territory, because this is now done not by moving your character

to various areas of the screen, but by waving your cursor around it, waiting

for it to turn into a direction arrow at some point — and some of these

transition points are actually quite tricky, even undetectable by the naked

eye. In terms of non-standard

«interesting» actions, Phantasmagoria

is surprisingly sparse: clicking on objects and putting things on top of

other things is pretty much the only thing you can do in the game. No tile

puzzles, no secret combinations, no mini-games, no deciphering secret codes,

not even an extra lesson of Latin for poor Adrienne. The closest you come to

anything «special» are the timed sequences in the last chapter, where

Williams and Seibert worked hard to put you into the real shoes of a victim

running away from a maniac — although, given just how many times most people

end up dying in that chapter, I am not sure that they achieved a perfect

result. (Too many dead ends, for one thing — though, admittedly, it is

possible to make your way out of some of these dead ends if you react quickly

enough with the right tool). Overall, Phantasmagoria demonstrates very well

most of the frustrating limitations of the FMV format; but due to the very

nature of the game, it could be argued that some of these actually work

toward its goals — making you feel shut-in, helpless, and painfully limited

in options against an impending evil. |

||||

|

To put it as simple as possible, I like Phantasmagoria.

I do not «love» Phantasmagoria, but I would never call it a failure, or

join the side of those who insist that the game is only good for a cheesy

laugh, and has always been that way from the very start. As I have already

stated many times, it would never work as literature, it would be a total

disaster as a movie, but it can achieve its purpose — stir up, if not

mess up, your emotional constitution — if you clear your mind from idiotic

preconceptions before launching the game. (For some reason, I am in this

respect reminded of my first experience watching Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove:

expecting a «comedy», as the young and dumb me was told by every single

source in existence, I sat down probably expecting to see something along the

lines of Pink Panther, and ended up puzzled, confused, and

disappointed. Words can be dangerous that way). Of course, Phantasmagoria commits

many errors, not all of which may be excused by the pioneering and

experimental nature of the game and some of which ascend to the level of

artistic crime (such as the amateurish mix-up of medieval and modern aesthetics,

for instance). But when the game is at its best — which, strange enough,

happens more frequently when you are walking alone through the Mansion,

rather than interacting with somebody in a cutscene — it is scary, or,

at least, unsettling (which is actually better than «scary»). As a passively

perceived stab at an artistic statement, it does not tap into the darker

sides of human nature in any sort of original way; but it succeeds — okay, it

can succeed — at taking you by the hand and making you cross over the

other side of that looking glass to immerse you in these dark sides in a way

in which you have never been immersed before. Not in 1995, at least. Since then, survival

horror has become such a common genre, done in such fine ways, that it would

be hard to imagine anybody who’d take Phantasmagoria over Resident

Evil or Silent Hill. But what with it being an adventure game,

after all, rather than a horror-themed shooter, Phantasmagoria still

remains a one-of-a-kind experience for those of us who like to take that

suspense at a slow, leisurely pace, unriddled with zombies or other monsters.

Replaying it recently for the purpose of writing this review, I actually

admired it even more than I did before — just because I literally have

trouble coming up with a better example of a game in which so many

things go so dreadfully wrong, yet it still manages to beat the odds

and achieve its primary goal. Well done, Mrs. Williams, for making me

sacrifice my critical credibility. |

||||