|

|

||||

|

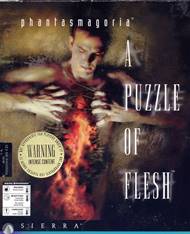

Studio: |

Sierra

On-Line |

|||

|

Designer(s): |

Lorelei

Shannon |

|||

|

Part of series: |

Phantasmagoria |

|||

|

Release: |

November 26, 1996 |

|||

|

Main credits: |

Director: Andy Hoyos Music: Gary Spinrad |

|||

|

Useful links: |

Complete

playthrough (5 parts, 290 mins.) |

|||

|

Basic Overview The market law is harsh,

but it is law: the massive commercial success of Phantasmagoria

more or less put an imperative to Sierra that a sequel should be produced as

soon as possible. There was one problem, though: Roberta Williams was not

interested. She had already endured the hardships of working on two equally

challenging and innovative games at the same time (King’s Quest VII and the first Phantasmagoria), and quickly understood that she could succeed

only if she’d hand the creative reins over to another designer for at least

one of them — thus most of the work on King’s

Quest VII ended up in the hands of Lorelei Shannon, a former writer of

guides and hintbooks for Sierra. For the next King’s Quest game Roberta was determined to take back control —

the Great Mother of the Kingdom of Daventry simply could not bear the idea of

abandoning her child for good. This meant that the sequel to Phantasmagoria would have to go to

somebody else. Who? Why — Lorelei Shannon, of course! The most important twist that Shannon

introduced to the Phantasmagoria

franchise was that the second game in the series would not be a sequel, or a

prequel, or, in fact, in any way

related to the first title other than through a general theme of horror and

the supernatural (as well as a brief Easter Egg reference). In this way, Phantasmagoria could become Sierra’s

own equivalent of The Twilight Zone

— the first such «thematic series» in the company’s history, presenting

players with story after story that would simultaneously challenge your brain

and creep out your senses. That said, I do not know if there were any serious

plans to make Phantasmagoria 3, and

this is largely irrelevant because Sierra’s former owners and employees would

lose the possibility to make any serious plans whatsoever pretty soon after

the shipping of A Puzzle Of Flesh. What is relevant is that, upon release, Shannon’s game made nowhere

near as impressive a mark on the gaming world as the original Phantasmagoria. Most of the reviews

were starkly negative, and sales figures are hard to locate — clearly, they

were nowhere near the level of Roberta’s brainchild. The main reason for this

was that the game already seemed to drag behind the times: FMV may have been

all the rage in mid-1995, but by late 1996, the format was entering its death

phase, as players who were formerly intrigued by gaining control over live

actors eventually became disillusioned by the cumbersome nature of the format

and the lack of genuine challenge. To smash the all-pervasive cynicism, a new

FMV game had to be damn, damn good,

and A Puzzle Of Flesh... just

wasn’t. Critics ripped it to pieces on all fronts — stupid, hole-ridden plot;

piss-poor acting; clumsy control schemes and stinted gameplay; frustratingly

trivial puzzles, other than a few frustratingly difficult ones. In short, all

the flaws of the original Phantasmagoria

multiplied by the lack of a novelty effect. At least Roberta Williams was

taking the first steps in a new, uncharted medium; Shannon, insisted the

critics, was merely repeating her predecessor’s mistakes. This judgement is only partially true.

As we shall see below, A Puzzle Of

Flesh does take home plenty of lessons, and it does improve in a whole

variety of ways on the flaws of Phantasmagoria

— even if these improvements were insufficient in their own time to redeem

the fate of FMV-based games in the eyes of consumers and critics. Most

importantly, though, Shannon’s game is simply a whole other beast. Where

Roberta’s fantasy, as it had always been in all her games, was fixated

squarely on the past (Phantasmagoria

is essentially Victorian Gothic horror stupidly placed in purely nominally

modern times), Lorelei instead conceived and produced a distinctly modern

game, not so much because of its sci-fi elements but mostly because of its

emphasis on relations, sexuality, and psychotherapy — all of these elements

still relatively novel for videogames (particularly the gay / bisexual

features of the characters). In some ways at least, it was a stab at making the single most serious and mature

game in Sierra’s history up to that point; certainly nothing even remotely

close to it could ever have been produced at LucasArts or, in fact, by any

other game studio in 1996. If you take a look through the user

reviews of A Puzzle Of Flesh on the

Steam, GOG, or other websites, a fairly frequent judgement, well visible

above the foundation of squarely negative assessments, will go something like

this: «Objectively, it’s quite a bad game that cannot be successfully

defended... but there’s something really special about it that makes me love

it in spite of all its awfulness». «Demented masterpiece», «something you

have to see to believe» — such phrasings are found commonly even in reviews

whose authors dish out one star out of five (then probably run back to

rewatch all the juicy scenes with sex and gore). My own position is even more

sympathetic: since I prize plot-based video games more for the effort

invested in world-building and immersing the player in the atmosphere than

for the actual «gaming» elements, I can easily forgive A Puzzle Of Flesh some of its more egregious flaws — and

wholeheartedly embrace and even fetishize the idea that no other PC game I

have ever played managed to be more disturbing and visceral. Well, there’s

always survival horror, of course, but that’s creepy feelings of a whole

other nature. Over the years, the game has managed to

accumulate a small, but loyal cult following, which has even prompted the

original lead actor, Paul Morgan Stetler, to set up a special channel in its

memory (‘Conversations

with Curtis’) — it ran out of steam fairly quickly after a set of curious

interviews with most of the other actors, but it does offer quite a few

goodies for those who are steadfast and true (the best gift is probably 25

minutes worth of terrific

quality uncompressed video from the game). That said, it would be useless

to ascribe this mini-phenomenon to anything other than sheer nostalgia, or to

deny that A Puzzle Of Flesh is,

first and foremost, a cultural artefact tightly restricted to its own epoch.

Our task, then, is to determine if there is any reason whatsoever to revive

that relic for modern or future players, other than purely historical, so

let’s get to it. |

||||

|

Content evaluation |

||||

|

One thing you can say for

sure is that Lorelei Shannon operates on a seriously broader scale than

Roberta Williams. If the

original Phantasmagoria was more or

less structured as a short story, with all of the game’s content packed into

one cohesive storyline, Shannon’s oeuvre feels more like a short novel, with

several connected, but distinct threads running through it — threads that

never really manage to smoothly connect at the end, but for a while,

intertwine fairly intensely for us to really notice that putting them all

together does not make too much sense. The main narrative concerns you playing

as one Curtis Craig, a young, nerdy, neurotic employee at a large

pharmaceutical company called Wyntech, where you typicall spend your days

confined to a tiny cubicle in which you mechanically write up assorted

documentation for various drugs and stuff. Apparently, this is an inherited

job, since your father used to work at the same place — that is, before he

was gunned down in cold blood right in front of his house, for reasons

unknown. This troubled past may or may not underlie the various illusions,

nightmares, and hallucinations that Curtis begins to experience on a regular

basis everywhere he goes or stays, be it at home, at work, or at either one

of the remaining two or three places in which the game generously allows you

to hang out. So it is Curtis’, or, rather, your sacred duty to get to the bottom of this situation, take a

little psychotherapy, unravel your twisted path, and find a suitably Freudian

cure for all the shit you have to endure. So far, this is all mostly Hitchcock’s Spellbound. Unfortunately, after a

short while Curtis’ surreal visions start to become supplemented with fairly

realistic — and gruesome — murders of his co-workers, one after another, at

which point it all shifts to Fincher’s Se7en.

There will be staplers, sledgehammers, electrocution, and other delightful

little inventions which certainly rival the almost equally inventive ways of

murdering people as seen in the original Phantasmagoria

— in fact, they almost rival the fatalities of Mortal Kombat, with the exception that everything here is taken deadly

serious. It will take Curtis some time to realize if it was really he who did away with all these

people... and the realization will be far from obvious. If Hitchcock and Fincher are too

lightweight for you, welcome to Venus

In Furs as the game throws yet another, almost entirely autonomous, line

at you. It is not enough that Curtis is having an affair with his pretty

straight work partner, Jocilyn, while at the same time experiencing a clear

pull toward his pretty gay work partner, Trevor; in addition to that, another of his co-workers, the

audacious Therese, insists on having him as her BDSM partner, because few

things in life are more fun than getting to whip the shit out of a skinny

nerdy guy with glasses. On the other hand, what’s better than a little

distraction at the local BDSM club when you keep getting hallucinations of

yourself as an axe murderer all day long? Throw that one in, too, with a

navel piercing on top. Finally, about halfway into the game it

becomes clear that there is going to be a major sci-fi twist to all of that —

involving no less than an alternate universe, an illegal barter system with

mysterious aliens, a substitution of identity, and a bizarre, messy finale in

which Freud, Stephen King, and, uh, Ed Wood are all invited on the

development team. This is where we fly out into yet another dimension, well

beyond The Twilight Zone, and begin

wondering about just how much Lorelei Shannon really wanted to bite off,

before the team went off the budget and was forced to cut more content than

Orson Welles on The Magnificent

Ambersons, ultimately reducing the last stretch of the game to a

senseless, barely comprehensible mess. I am not saying that, had A Puzzle Of Flesh been an actual novel

(and it is strange that Shannon, who would go on to become a professional and

frequently published writer, never attempted a novelization), it would have

become a genre-blending masterpiece of sci-fi horror. At best, it might have

enjoyed the popularity of a second-rate Stephen King work. But given that

there were actual movies that managed to eclipse whatever literary

significance there might have been in King’s oeuvres (such as Carrie or The Shining), an FMV video game based on that kind of subject could have been a success — at least,

in theory, what with the medium’s special advantages helping take the focus

away from the inane elements of the plot. However, the major problem is that the

plot of this game seems to be totally

subdued to the very fact of its being a game. When you put all of it together,

you do not get an impression of a cohesive story, whose separate elements all

serve any global, general purpose. The basic line of thinking here is more

like «okay, what should a modern,

progressively-oriented, innovative adventure game about the supernatural have

in it?» At least Roberta’s project followed some sort of unified, if

extremely naïve and shallow vision; Lorelei’s is just all over the

place. Need a bit of really brutal gore — check. Need us some rough and kinky

sex — check. Need aliens from another dimension — check. Need to expose

greedy, sinister, man-eating corporations — check. Need to promote

psychotherapy — check. Need a sympathetic gay buddy — check. Everything is

thrown at the walls with the primary purpose of Featuring Mature and Disturbing

Themes in a Video Game; the purpose of making you sit back and think on what

the hell it is all supposed to mean is distinctly secondary. When the ultimate truth is finally

revealed, it’s not even as if it does not make sense (because it does), or as

if it does not have any moral points to it (because it does — the moral of

the game is that everybody is an asshole). The worst thing is that it feels

like a barely believable copout. For about three quarters of the game’s time,

it is possible to keep an open tab on Shannon and even tolerate some of the

painfully generic psychotherapeutic clichés she flings at you from

inside the doctor’s office — since there is a genuine element of intrigue

involved. Once that intrigue gets murdered in a ridiculous gust of sci-fi

melodrama, the entire house of cards comes crumbling down. Could it have been

handled better if the game’s ending was not so rushed? If we were given an

extended chance to wander around the four corners of «Dimension X»? If we

were let in on more details from the early life of the «real Curtis» and the

«imitation Curtis»? If we actually got to understand how Jocilyn, the love of

Curtis’ life, got wind of the Project? If we got a better notion of the

significance of the entire BDSM angle to the story? I don’t really know the answer to these

questions; all I know is that, whenever I replay the game, I usually lose

interest right after the final murders, and absolutely hate to go through

Curtis’ final adventure in Dimension X (though, to be fair, the illusionary

sequence in which he is chased around the facility’s wreckage by his

zombiefied colleagues is creepy fun). But to me, that does not immediately

negate the impact of the main bulk of the game — and given how well

accustomed we are these days, for instance, to TV shows that start out great

and end on some ridiculous note of shame (just because the principal writer

never bothered to properly think out the ending when pitching the proposal),

there is no reason why the same kind of TV logic could not be applied to a

video game as well. If your ending seems to be taking a dump on everything

that made the game intriguing, just erase it from memory — and invent your

own, if it’s that important to you. To me, it is more important that out of

the three FMV games produced by Sierra, A

Puzzle Of Flesh is the one featuring the most realistic dialogue and

action sequences from its live actors. Gabriel

Knight: A Beast Within unquestionably had a far superior plot and far

stronger emotional highs, but Shannon really made a strong emphasis on her

FMV heroes behaving like real people in a real environment — for which

purpose she wrote tons of realistic, often (though not always) intelligent

and occasionally funny dialogue. Possibly my favorite parts of the game are

the ones in which you are allowed to simply cruise around your office,

phoning or directly hitting on your various co-workers — particularly Trevor

— and chatting them up on various topics, either related to your trials or just

completely off-the-wall. Naturally, Shannon ain’t no Tarantino when it comes

to disclosing the transcendental aspects of the mundane, but this here is

still a kind of dialogue that you will never, ever witness in any other

adventure game from Sierra On-Line: Curtis: Hey,

bud. How was your second date with the mysterious Jay, huh? Trevor: A dud.

Big time. I mean, once I got past the sexy eyes, the gorgeous cheekbones, I

saw the squid beneath the skin... Curtis: Oh,

what a drag. Trevor: You’re

telling me! He spent half the evening picking apart Bela Lugosi’s acting, and

the other half staring at his own bad self in the bathroom mirror! Curtis: He

doesn’t like Bela? Trevor: Mmm-hmm. Curtis: Well

piss on him, then! Is this great off-the-wall dialogue?

Not in the slightest. Is this the kind of dialogue you’d ever expect to see

in a 1996 adventure game? Certainly not. Is this the kind of dialogue that

two real people in 1996 could have been having between themselves? You bet.

Especially if both were fans of Bela Lugosi... and, maybe, a little Pulp Fiction. For all the corny sci-fi

shit that Shannon throws at us, A

Puzzle Of Flesh is surprisingly gritty and realistic in its smaller-scale

moments: the business stuff, the police procedure details, the swinging gay

attitude of the adorable Trevor, and even the portrayal of the BDSM community

(in which Shannon was seemingly quite invested herself, but I really don’t want to know). As long as

you never forget to apply the usual disclaimer — that you have to judge all

of this stuff against other video games, not against great cinema or

literature — the story and the overall everyday world of A Puzzle Of Flesh emerge as true accomplishments for their

specific era. It is just that, unfortunately, the flaws of the production are

so much in your face that they are often easier to concentrate on than the

virtues — probably a typical situation for each FMV game ever made. |

||||

|

This, alas, is an area

where kind words are hard to come by — which automatically means that, since A Puzzle Of Flesh is after all a

puzzle-solving adventure game, it is just as much a bad game as its predecessor in the series, which is not the same

as saying it is a bad experience, but still results in lots of merciless

one-star ratings from amateur reviewers. Fact of the matter is that, while

Lorelei Shannon did have her own vision for the universe, atmosphere, and

storyline of the game, she had relatively little interest in envisioning it

as a set of actual challenges. In fact, something tells me that she might

have thought any serious challenges would only confuse and irritate the

players by unnecessarily hindering them from learning what happens next.

Consequently, not only does the game fully embrace the simplistic mechanics

of Phantasmagoria, but it generally

makes things even easier for you, as if that was possible. Consider this: 1. Phantasmagoria

at least took place inside a huge mansion with many rooms, specific details

and objects within which could change from chapter to chapter, stimulating

exploration — furthermore, most of the time you could also make excourses

into the small, but important outside world, just to check if the solution to

your current puzzle lay anywhere within its boundaries. In contrast, the

world of A Puzzle Of Flesh is most

of the time limited to two measly rooms of Curtis’ apartment and the tiny

space of his work office — all the other areas open up only at specific time

intervals when they are truly needed. How hard can it be to do whatever it is

you’re supposed to do if your choices are that

limited? 2. While we may all generally hate

pixel-hunting for hotspots on the screen, A

Puzzle Of Flesh goes way too far in trying to eliminate that hassle. Your

cursor, an enlarged logo of the Wyntech corp, is absolutely frickin’ huge, and finding the right hotspot on

the screen is every bit as difficult as clicking on a blazing neon sign that

says CLICK HERE. In addition, the

number of such hotspots is extremely small, since, just as in Phantasmagoria, 90% of them serve

important pragmatic purposes — you will never have Curtis just

absent-mindedly comment on some insignificant detail for a bit of trivia or a

light joke (as could still be the case in Gabriel

Knight: The Beast Within). 3. Inventory objects can usually be

acquired only at the precise time moment when they are actually useful, never

earlier than that, so you won’t waste any time trying to fruitlessly apply

them to everyone and everything in sight. For instance, there is a table in

an auxiliary room at Wyntech which you can look at but can do nothing with.

On a certain day, a hammer appears there that you can pick up and use. Why

wasn’t it there from the very beginning? Because you’d have no need for it

(actually, not quite: the correct answer is that because you would have been

able to solve a particular puzzle earlier than necessary for Shannon to

progress the story). Other than that, «puzzles» are usually

of the same variety as in Phantasmagoria:

find the right object X, use it on the right object Y. The very first of

these was a methodological disaster that has since figured in nearly all reviews of the game, since (a) it

looks extremely silly and (b) it is encountered so early on that it is

encountered even by those reviewers who never go further than the first half

hour of the game in question. It is, in fact, so silly and so easy that

talking about it hardly counts as a spoiler: in order to retrieve your wallet

from under your couch, you have to send in your pet rat Blob after it — then

get her to come out by enticing her with a candy bar. Naturally, this is a

great opportunity for writing stuff like «yeah, that’s totally me starting my every morning» and such — but, in

Lorelei’s defense, this bit of nonsense was most likely put up there just to

give newcomers to the adventure game genre a bit of early training with the

inventory system; none of the subsequent puzzles dare to be that defiant about common sense. As in Phantasmagoria, progress in the game will typically depend upon

your exhausting your options — such as talking to all of your co-workers,

which is also a bit clumsy because there are no specific dialogue options,

you just have to click and click on them continuously until y’all run out of

things to say. One logistic decision is particularly questionable: during

Curtis’ therapy sessions, he can discuss various topics with his doctor by

presenting her with select inventory items out of his pocket — so, instead of

an actual verbal menu with options like «talk about parents», «talk about the

murders», «talk about BDSM», etc., you have to symbolically «give» the good

doctor bits of your mother’s lace, a button off a victim’s shirt, an

invitation to the club from Therese, etc. This seems to be less of an

artistic design decision and more of a last minute workaround in a situation

where you need a dialogue menu but

cannot have one just because the previous designer left you with a crappy

game engine. (Jane Jensen was able to overcome that obstacle by showing that

dialogue menus are by no means incompatible with the FMV system; Shannon,

apparently, did not care). All puzzles have completely

straightforward solutions; the option of choice is limited to the possibility

of answering in several different ways to E-mails from your friends (as usual

in such cases, I always recommend «sarcastic» or «funny» answers over

«straight» — there are no consequences anyway, other than receiving

correspondingly varying mini-answers). The only «big» choice you are allowed

to make comes at the very end of the game, triggering one of two possible

endgame videos — again, if you are too lazy to go back and replay the

sequence, I wholeheartedly recommend staying on Earth with Jocilyn, since the

corresponding mini-video is a tiny bit less «vanilla» than the other...

essentially, it does not matter, though. Most of the «non-standard» puzzles in

the game are every bit as trivial as the regular ones — typically, they

involve guessing computer passwords (which usually stare you right in the

face from less than two meters away), and at one point you are supposed to

gain entry into «The Pit» at the BDSM club by solving a construction puzzle

requiring the mighty intellectual level of a 2-year old (maybe it was

Lorelei’s subtle hint at the average IQ of the average visitor to a BDSM

club, but such offensiveness would sort of negate the entire point of

including that part, wouldn’t it?). There were, in fact, only two times in

the entire game where I got hopelessly stuck and had to submit to a

walkthrough. The first one required me to combine two objects in the

inventory in a pretty specific way to unlock a secret compartment — which was

pretty mean, considering that this was the very first time that the game

required you to combine anything and

that using both objects separately led to failure and not the slightest hint

that they should have been combined. The second one you have most certainly

guessed if you already played the game — and yes, it is yet another reason to

abhor the final section, taking place in «Dimension X». In order to get back

to Earth, you have to start up some sort of infernal engine by performing a

lengthy and tedious series of operations without an instruction manual,

essentially getting on by trial and error alone. This Incredible Machine-style monstrosity appears totally out of the

blue, feels more complicated than all of the game’s other puzzles combined, irrepairably ruins the

immersive effect, and seems to act as a time-wasting substitute for the lack

of a properly filmed ending. Imagine being able to take a day trip to London,

except you’ve been taken directly to Big Ben and have to spend the entire day

studying the mechanics of its cogwheels — this is the direct equivalent of

Curtis Craig’s adventure in Dimension X, no more and no less. If not for situations like these, one

might simply want to take it easy and accept that A Puzzle Of Flesh is the closest Sierra ever got to a simple

interactive movie, an experience that merely wants to put you in the shoes of

the protagonist, gently take you by the hand and guide you through a set of

easily openable doors, rather than make you wrack your brain. Unfortunately,

every once in a while this nice, perfectly enjoyable interactive movie just has to remind you that it is also a

piss-poor adventure game. It is entirely up to us, then, if we prefer to

dwell on this, venting our frustration in the form of one-star reviews, or try

to put the torture out of our minds as soon as possible and just move on to

discuss the juicy part of the experience — its atmosphere. Personally, I prefer

to take the positive route and vouch for the latter. |

||||

|

Every now and then, I come

across an assessment of A Puzzle Of

Flesh that goes something like, «this is the videogame equivalent of a

decent / tolerable / crappy B-movie», and for some reason, these comparisons,

understandable and justified as they are, irritate the heck out of me. Maybe

it is because, from this perspective, 99% of videogames ever made, even some

of the very best ones, are really equivalents of B-movies — after all, where

is that special videogame whose level of writing would be on par with Woody

Allen or David Mamet? In reality, videogames can allow themselves to be way

below the level of creative standards acceptable in more «noble» media when

this is compensated by the advantage of making you an active part of the experience. A Roger Corman movie is

certainly «B» when it is a movie; but make it into a good interactive movie, and presto, you’re

eligible for an upgrade. Let’s face it — would you rather be willing to play

a game based on The House Of Usher

or, uh, I don’t know, The Seventh Seal?

(And please do not rush to answer

even if you happen to be an intellectual snob...). In terms of sheer

atmospheric pressure, A Puzzle Of Flesh

is perhaps the single most unique, if not to say manipulative, game in the

Sierra canon — and much of this pressure is achieved almost by accident. One

thing that Shannon and her filming crew did not want to do was rely upon the

blue screen approach: apparently, they saw the results of the original Phantasmagoria as well as the second Gabriel Knight game and decided that

it all looked way too artificial and clumsy (in which they were absolutely

right). So most of the game was actually filmed in a real studio — and since,

obviously, Sierra lacked the budget to construct a large set, everything had

to be shot indoors. There are practically no outside shots in the game at

all. You have Curtis’ tiny two-room apartment, Curtis’ cramped working space,

some narrow corridors from Curtis’ hospital and Wyntech’s evil basement, Dr.

Harburg’s office, and a few other spots, movement between all of which is

automatic (you never see Curtis taking any form of public transport). Above everything else, this

makes A Puzzle Of Flesh

excruciatingly claustrophobic. The apartment is bad enough, but the sight of

Wyntech’s working space — a set of tiny cubicles separated from each other

with green panels, without a single window in the room — is enough to get you

thinking that one could so easily

go nuts in this kind of environment, even without a troubled alien past or a

psychotic mother hunting after you with a pair of garden scissors. Whenever I

had to spend any amount of time in that place, sorting out the E-mails and

recovering lost passwords, I eventually caught myself walking over to the

center of the room to take a drink from the water cooler just to escape that

painful feeling of being locked up — and that’s coming from a pretty

introverted person. A stark contrast is found

between Wyntech and the scenes in Dr. Harburg’s office, which were filmed in

broad daylight with the windows partially open and letting in natural

sunlight (at least, I think it’s

natural — it is hard to tell with all that video compression going on). Even

then, with the curtains partially drawn and electric lights providing their

own counterpoint from inside, the produced effect is odd rather than

optimistic: it’s as if we are being relocated from the hell of Wyntech into a

virtual «twilight zone», a limbo of sort from where there is a fifty-fifty

chance of things getting better or worse. In any case, heading off to those

sessions does provide the sense of temporarily stepping into a relatively

safe zone, and so do the occasional bits of relaxation with your friends

Jocilyn and Trevor in the Dreaming Tree

diner. Unfortunately, both locations are only available at specific times,

whereas the hell of Wyntech is pretty much always open — except for a few

times when the police are busy scraping off evidence from the latest murder. «Claustrophobic» is, of

course, only one of the associations; a far more intentional one was that of

«nastiness». Apparently, David Fincher’s Se7en,

which I already mentioned above, was a real influence on Shannon; and even if

she only borrowed the very idea of a sequence of exotically arranged killings

from the movie, without bothering to copy the idea of their symbolism, the

seemingly gratuitous violence is still unnerving when it is you who get to walk around the

premises and keep receiving hints that this might all be a result of your doings. (The first murder, for

instance, is not actually shown in its own timeframe, but only as a series of

flashbacks when Curtis arrives upon the crime scene). In any case, the claustrophobia

and the nastiness, like the weak force and electromagnetism, eventually turn

out to be two sides of the same coin — make you, the player, as uncomfortable

as possible. While I won’t go as far as to say that A Puzzle Of Flesh is capable of driving a sane person crazy, I

would certainly recommend you to stay away if you already have plenty of

psychological problems as such. As to what concerns the

BDSM angle... well, the entire thing is fairly clichéd and probably

not even up to the level of Fifty

Shades Of Grey, let alone anything more serious, but visually and

sensually it does fit in with the «nasty» feel of the game. There is no

attempt to somehow sugarcoat or romanticize the whole business — from the

unsavory types inhabiting Therese’s favorite club to the grossly grotesque

scene of Curtis getting his navel piercing to Therese’s own stalking behaviour,

it’s all about wallowing in delightful depravity, and when Therese herself

finally gets what’s been coming to her, it is probably the single most Se7en-like moment in the game — as in,

isn’t getting electrocuted in your own blood the highest possible BDSM

experience there is? It is highly likely that

you will walk away from the game feeling filthy; it is almost as likely,

especially in our deeply sensitive age, that you will walk away feeling

offended, one way or the other. If anything, it might not so much be the

equivalent of a B-movie as it could be the equivalent of listening to a G. G.

Allin record — okay, that might be going too

far by way of analogies, maybe swap that with The Birthday Party. It’s heavy,

really heavy shit, and certainly

totally un-fuckin’-believably heavy shit for Sierra On-Line: I am not even

certain that Ken or Roberta Williams actually saw the final product, or they and

their family values might have pulled the plug on it (then again, Ken was

probably way too busy selling Sierra’s ass out in 1996 to pay much attention

to the creative side of the business anyway). Oh, and yes, the less said

about the atmosphere of the game’s final segment, the better. «Dimension X»

was the one part of the game where they had no choice but to use the blue

screen approach, with Curtis’ sorry sprite lost and bewildered against an

alien landscape — which is not that badly portrayed, but can at best count as

a tiny appetizer for the real thing. (It’s a bit amusing to think that

precisely at the same moment when A

Puzzle Of Flesh was being released, Ken Williams was negotiating with

Valve over the publishing rights to Half-Life,

given how Curtis’ teleportation jump into «Dimension X» resembles, in more

ways than one, Gordon Freeman’s journey to Xen — and not only that, but both

protagonists have to carry out a brief mission of neutralizing the big baddie

and going back!). The imagery is not bad, the little alien amoebas are cute,

and the music is appropriately sinister, but you will be spending most of your

time dealing with the infernal engine machine anyway. In a perfect world,

Shannon and crew might have been able to properly depict «Dimension X» as a

wond’rous and desirable alternative to Curtis’ sorry existence in his Wyntech

cubicle, but... budget is budget. |

||||

|

Technical features |

||||

|

Of all the Sierra games ever made, A Puzzle Of Flesh was probably the one

that required the least amount of graphic artistry; this was because, in

contrast to their two previous FMV efforts, most of the action was filmed in

a real studio, rather than against a blue screen that would later be filled

up with (at least partially) painted art. Like most innovative decisions,

this one, too, had both its pluses and minuses — the inevitable negative side

effect was that most of the backgrounds could only look as rich, detailed,

and imaginative as they would arrange them in the studio, which ultimately

meant not rich and imaginative at

all. Compared to the cheesily opulent bedrooms of the Carnovasch Mansion in Phantasmagoria, or to the glamorous

Bavarian scenery of Gabriel Knight 2,

Curtis’ living room and cluttered work cubicle are not much to look at, nor

are the interiors of Dr. Harburg’s cozy office or those of the grimy,

nasty-looking Borderline club. The static backgrounds are largely

perfunctory, and the game’s cutscenes place 99% of the emphasis squarely on

character acting and nothing else (well, I’d say those chocolate shakes at

the Dreaming Tree that the characters never seem able to finish look pretty

appetizing, but that’s about it as far as possible distractions are

concerned). Only one small section of the game has

no choice but to systematically integrate live action with CG art, and that

is the alleged «Dimension X», of course, to which Curtis is forced to make his

own proto-Gordon Freeman trip. Some credit has to be given for the artist who

designed the place, and judging by the amount of detail and by the clearly

visible struggle for imagination reflected in that work, they had to make

really serious cuts to the segment — wasting all that effort on three or four

screens worth of material would have been quite painful for the original

artist. Oddly enough, «Dimension X» kind of fits in visually with the overall

nasty look of the Earthly locations

in the game: it is a weird and intriguing-looking place, but in a dangerous

and disgusting sort of way, which makes the resemblance to Valve’s Xen all

the more striking. With its odd shapes, sickly blue and green colors, creepy

bio-engineering devices, and potentially lethal local life-forms, it does

look a lot like what Xen could have looked like if it were represented by

static 2D backgrounds rather than 3D polygons. Too bad that most of your time

in that place will be spent trying to disentangle that doggone infernal machine

(see the Puzzles section). But let us now get back to the main

bulk of the game and talk a little about its main visual lure — the acting. Now it is more or less a given

that just about any review of the game, professional or amateur, will almost

inevitably mention «bad acting» as one of its principal flaws. The tricky

situation here, though, is that it is all but impossible to load up the game

and not expect bad acting — because

(a) FMV games are not supposed to have good acting, (b) Brad Pitt and Nicole

Kidman are not listed in the

credits, in fact, nobody you know is listed in the credits, so they must be bad actors. Plus, it’s a game

about gruesome murders, wild kinky sex, and aliens, so it’s gotta be bad acting. Truth is, it’s not bad. Not a single performance here is genuinely outstanding on

the level of Peter Lucas in Gabriel

Knight 2, but cumulatively, I would say that A Puzzle Of Flesh is the best acted out of the three Sierra FMV

games, and that out of all the actors who get more than three or so lines of

dialog, not a single performance strikes me as particularly overwrought or

cringeworthy. For some reason, the only actress to have been carried over

from the original Phantasmagoria

was its worst nightmare — the abysmally clownish V. Joy Lee — but this time,

she only gets a tiny bit part, playing a mental patient in Curtis’ ward (a

role she still manages to flub:

just how bad an actor must one be to even fail to properly represent a

lunatic?). As for the main cast, their chief problems are not so much in

portraying believable or empathetic characters as in coping with the excesses

of the dialog — which, as I have already mentioned, tries as much as possible

to be more mature and realistic than in previous Sierra games, but still

cannot help frequently borrowing from the pool of genre clichés

(Jocilyn’s "right now, I just

really need to feel you inside me" certainly takes the cake, but

neither can we forgive the stereotypical Big Bad Corp Guy Paul Warner or the

equally stereotypical Dumbass Cop Allie Powell — "I don’t have to listen to DICK, Craig!"). Even so, there is

clearly a whole lot of commitment here, and if it feels as if sometimes the

actors are hamming it up a bit too much, this can be excused by the nature of

the medium — acting exaggeration was as much a given for FMV shoots as it was

in the era of silent cinema, since the necessity of video compression for the

CD format required the videos in question to be as «expressive» as possible

(this also explains why there are so many close-up shots — the only way you

could properly see the characters’ faces was if they occupied the entire

screen). Paul Morgan Stetler, the actor playing

the main role of Curtis Craig, gives quite a believable performance — if you

were a shy, nerdy, secretly bisexual bespectacled little guy with a history

of mental illness, tormented by hallucinations and suspicions of

schizophrenia, you would most certainly be able to empathize with the

character. Again, it is not quite his

fault if you get tired of all the times he has to take off and put back on

his glasses, or freak out in front of the mirror, or go off his rocket before

his psychotherapist: blame it on the script which often runs out of creative

ideas. At least it gives Stetler many more opportunities to show various

shades of emotion, from humor to terror, than poor Victoria Morsell received

in the first Phantasmagoria. Out of Craig’s two conflicting love

interests, Paul Mitri as Trevor receives the top award: his performance even

has a historical significance in that it was one of the first, if not the first, relatively

non-clichéd portrayal of a gay character in a video game. Mitri’s

Trevor is certainly flamboyant and theatrical, but the flamboyance is shown

as more of a side effect of his sexuality than of his flaunting it, and he

has a gift for exuding charm and friendliness even through the corniest or

the most narcissistic of his dialog lines. I think he even manages to salvage

Shannon’s «Bunny And Potato»

story — every now and then, she gets the urge to prove to us how much she’s

learned from Tarantino’s movies but never really gets it right all by herself

(the side stories just lack the required kind of offbeat nature and humor),

yet Mitri somehow turns this little bit into one of the game’s most endearing

moments. (Considering that the best performance in Gabriel Knight 2 was given by Peter Lucas as the clearly

homoerotic-minded Baron von Glower, I’d say Sierra’s producers had quite a

solid sense of the LGBT spirit back in those out-of-the-closet Clinton

years). For Curtis’ other love interest,

Jocilyn, they went out of their way to actually hire an established erotic

movie starlet, Monique Parent (IMDB: «an

American actress known for smoldering love scenes and intensely charismatic

characters; she has been called The Thinking Man’s Sex Symbol» — yes, and

she must have some really good PR agents). I suppose this was mostly

necessary because Shannon and Andy Hoyos decided to step up their game after

all and include some real nudity

this time, instead of that measly sideboob flash nonsense in Phantasmagoria — yes, horny players

all over the world rejoice, because we do get to see Monique’s tits in all

their 640x480 pixel glory, if only for a couple seconds. Other than that,

though, she has to play the role of sweet nice girl without a clue about

what’s going on, which doesn’t exactly give her any opportunities to shine,

but she pulls her functions off reasonably well, no serious complaints here. Of course, bad girls always win next to

good girls, so it is no wonder that the Best Actress spotlight here is stolen

by Ragna Sigrun as Therese Banning, steady office worker by day, mighty BDSM

queen by night — and, again, probably the first video game character of this

type in the genre’s history. Here, it is supposedly the Basic Instinct influence prevailing over Reservoir Dogs, and although, like Jocilyn, the lady is given

only one dimension to play around with — the opposite one — she does a good

job of reminding us guys about the nature of temptation (just how many bored

white collar office workers secretly wish they’d

have a work partner just like that?). Ironically, her tits are never going on show in the game — apparently, the

Devil prefers to entice her clients with sexy leather instead, whereas the

Angel is more about taking it all off. None of these guys ever went on to

anything big — in fact, all of them seem to have left their acting days

behind them, which could be

interpreted as proof that they were really bad actors starring in a really

bad video game, but... not really. If you play Sierra’s FMV games in their

precise chronological order, from Phantasmagoria

to Gabriel Knight 2 to A Puzzle Of Flesh, it is impossible

not to notice how quickly the acting techniques, the angles, the

cinematography, the dialog improves with each subsequent title, and it

actually makes me a little sad about the demise of FMV as a viable artistic

and commercial strategy — much like the text parser in adventure games, just

when it was beginning to get a little better, new technologies came around

and throttled further development along those lines. (I do realize that

filming, say, The Witcher 3 in FMV

would have required the gaming industry becoming ten times more financially

powerful than the movie industry, but surely there could still be a viable

market for smaller-scale stuff, no?). Minor, but significant technical

detail: like most of the games at the time, A Puzzle Of Flesh was made available in separate DOS and MS

Windows versions, and the most commonly found digital version of the game

today (the one sold on Steam and GOG, for instance) is the DOS version,

because the lazy bums at Activision still have not found a proper way to make

Sierra’s old Windows games run well on modern systems. This is particularly

unfortunate for A Puzzle Of Flesh,

since all the video files in the DOS version are only available at lower

resolutions and with dreadful interlacing, making you feel as if watching

every damn cutscene through a French blind — and, unlike Sierra’s other two

FMV games, A Puzzle Of Flesh seems

to have never had a properly working patch to get rid of this nonsense. The

Windows version, in comparison, is far superior, with higher graphic

resolution and no interlacing — but you have to hunt for it (I ended up

downloading a pirated copy, and feel no shame whatsoever about this), and

then use a custom-made installer to play the game. No pain, no gain, right? |

||||

|

Okay, so, apparently, Gary Spinrad, the

composer of the musical soundtrack for A

Puzzle Of Flesh, has in more recent years become known as a live

impersonator of Elvis Presley and Gene Simmons... at

the same time. If this does not exactly get your goat, I don’t know what

else will, but really, this is one thing I like about these brief stints

people would pull off at classic video game companies in the 1990s — you can

never tell where they would end up in the future, but you can almost always

tell it’s going to be one or another

strain of really, really weird shit. Those were crazy times, and people would

take bits and pieces of that craziness away with them as souvenirs for the

(comparably) less crazy and more regimented 21st century. The actual soundtrack has pretty little

to do with Elvis or KISS, though. It is very

1990s — so 1990s it almost hurts — and mostly electronic, ranging from dark

ambient to industrial to beat-heavy early synthwave or whatever that stuff is

called (I should really brush up on all those electronic subgenre names from

the decade, but I figure it’s always fun to offend somebody when you forget

the difference between house and trance), in keeping up with the game’s far

more modernistic setting and sci-fi overtones as compared to Roberta

Williams’ retro-oriented Gothic flavor of Phantasmagoria.

Inevitably, its MIDI synths and gated drums will sound dated to modern ears,

but if the entire game is essentially a time capsule from 1996, why shouldn’t

the music be any different, as long as it suits the game’s purpose? I think that Spinrad is really at his

best here with the slow, atmospheric parts. As soon as you get control over

your character, the minimalistic minor key piano theme over a haunting

bedrock of woodwind synths generates a mournful, melancholic aura which does

far more to make you believe in Curtis’ haunting emotional traumas from his

past than the game’s aggressive introduction (Curtis receiving shock therapy

in the hospital). Then, once you get to Wyntech, the cavernous echo of the

slowly unfurling bass synth notes suggests that this is not exactly a safe or

welcoming place to be before you even get to settle down in your cubicle.

There are few, if any, «optimistic» themes — in fact, the safest places in

the game are usually distinguished by the relative lack of musical themes, e.g. the Dreaming Tree diner or Dr.

Harburg’s office, where the synthesizers are silent by default and only

strike up their grim march when Curtis experiences another hallucination or

something. The action-packed sequences, when shit

hits the fan and somebody gets murdered, predictably kick the soundtrack into

overdrive, which is not too much to my taste — I think that this kind of

percussion-heavy madness is more appropriate for the likes of Half-Life or other shooters; but I

guess this is the price we have to pay if we want us a proper 1996 time

capsule. What makes it worse is that the musical soundtrack is poorly synced

with the voice acting, so whenever the music is loud and fast I always have a

really hard time making out whatever the actors are saying (a situation

exacerbated by the lack of subtitles). If ever the game stands a chance of a

remaster (highly unlikely, but...), this lo-fi shit needs to be taken as much

care of as the resolution upscale for all the cutscenes. Finally, as is usual for Sierra, the

game finishes with a really crappy, cheesy, totally out-of-touch industrial-synth-rock

tune (‘Rage’) with viciously murderous lyrics, probably sung by Spinrad

himself — too pathetic, probably, even for the likes of Nine Inch Nails,

whose style it somewhat approaches. I honestly have no idea why all of

Sierra’s game music, often fine on its own, immediately began to suck as soon

as they’d add vocals to it — be it ‘Girl In The Tower’ from King’s Quest VI, ‘Take A Stand’ from Phantasmagoria, or this particular

piece of tripe (the only exception is Robert Holmes’ pseudo-Wagner opera in Gabriel Knight 2, but that was

obviously a very special case of do or die). At least with ‘Girl In The

Tower’, Ken Williams had a genuine ambition to hit the charts, which explains

why it had to sound like Michael Bolton; but these Phantasmagoria numbers, to the best of my knowledge, were not

exactly marketed as potentially commercial singles. Oh well. Who the heck

watches the credit rolls at the end of video games anyway? |

||||

|

Interface Although in general the

interface of the first Phantasmagoria

was retained, A Puzzle Of Flesh did

have a few subtle changes for the better. Obligatory, ever-present on-screen

hubs were removed, to appear only when triggered by moving the mouse across

the screen. The ridiculously superfluous hint system (Phantasmagoria’s rather moronic red skull) was gone for good as

well. The overall area of the screen covered by static backgrounds and video

cutscenes was much larger than before. Perhaps most importantly, you could

now properly save your game in different slots and restore it at any time,

instead of being limited to exactly one save slot per game (Shannon followed

here the example of Jane Jensen, who also wisely opted for a traditional

system of save slots when adapting Roberta’s new interface for Gabriel Knight 2). Movement from point A to

point B was completely eliminated from the game — unlike the other two FMV

titles, A Puzzle Of Flesh does not

allow you to move Curtis (or any NPC to move on his or her own) across the

static background, since the filming process limited blue screen usage to an

absolute minimum. In order to move from one room to another, you simply click

on an arrow and get automatically transferred to a new screen; in order to

move into a completely different area, you open an in-game map and select

your destination (like in Broken Sword

or other older games). This was a good thing to do, not just because it saved

you time and effort, but mainly because it made the game suffer a little less

from the «oh look how cool we are, now that we can move a live actor across

the screen!» bravado of Phantasmagoria

— the same bravado that made you spend a whole minute of your time watching

Adrianne slowly sit down on a sofa, fidget around for a while, then just as

slowly rise up again, for absolutely no other reason than «because-we-can»

(a.k.a. «immersive realism»). It is still possible for Curtis to waste time

on useless actions, but this has more to do with solving puzzles than with

pointless dicking around. In general, A Puzzle Of Flesh gives the impression

of a game whose creators have finally learned their lessons and no longer

feel as uncomfortable with the new format as their predecessors.

Unfortunately, the major problem — a jarring discrepancy in the visual,

sonic, and atmospheric properties of the cutscenes and the static interface —

remained as unsolved as it was in the earlier games. Transitions into and

from cutscenes are anything but smooth (the game can temporarily freeze

before throwing you in or out of the scene), music flow will be interrupted

and roughly shifted, graphic resolution change might wreak havoc on your

brain, etc. On the other hand, this is a problem which, in its final form,

has not been resolved even today — look at the Witcher games, for instance, whose cutscenes remain firmly

segregated from the main game flow, despite no use of FMV; so let us not give

the poor old title from 1996 too much flack just because its creators were

unable to move mountains. |

||||

|

Other than unsubstantiated accusations of

persistently «bad acting», I think that I can get behind every single

accusation ever thrown at Phantasmagoria: A Puzzle Of Flesh. It is a

pretty poor «game», it is a pretty corny «interactive novel», it tries to

bite off far more than it can chew in one go, it is visually and sonically

dated, and it has a terribly cheesy song at the end of it. And yet, none of

these arguments will ever make me forget it. One extremely important thing is

undeniable: A Puzzle Of Flesh was one of the strongest, if not the

strongest, efforts by Sierra On-Line, a firmly established, mainstream

mammoth of the mid-1990s gaming industry, to get out of its «comfort zone».

One might grumble that they did not go far enough (especially when compared

to such truly discomforting titles as I Have No Mouth, And I Must Scream),

or, vice versa, complain that they took it way too far with all the

gratuitous sex and violence stuff, but the fact remains that the game tried

to take the adventure genre to the next level of seriousness, and for all of

its flaws, the atmosphere of crazyass enthusiasm and audacity is more than

enough for me to forgive the game most of its sins. Given how common it has always been for

underage teenagers to be entertained by stuff targeted at higher age groups (just

how many kids greeted their entry into pubescence with a swiped copy of Leisure

Suit Larry?), I am pretty sure that plenty of today’s 40-year olds still

vividly remember the nightmares this game would give them when they first

laid their hands on it, expecting, at best, another Gabriel Knight.

Today’s largely sanitized gaming market would never accept this kind of

title, preferring to spook you out with far safer topics, such as the zombies

of Resident Evil or other survival horror. It is true that the promise

of A Puzzle Of Flesh is never properly fulfilled — at the end of the

game, we are not really too sure what these atrocities were all about, or

what Lorelei Shannon really thinks about the moral (and sanitary)

aspects of BDSM clubs. But we can, and will, remember that we have

just been virtually plunged in a strange, creepy, dangerous universe which we

shall (hopefully) never encounter that directly in real life, even if

you don’t really need to be a shape-shifting alien from Dimension X in order

to inflict that kind of bad shit on real people. In the end, I would say that A Puzzle Of

Flesh is the video game equivalent of movies like Peckinpah’s Straw

Dogs or Kubrick’s Clockwork Orange — the kind of stuff that

requires a good combination of strong stomach, curious brain, and firm moral

standards to get off on (not that I’d ever compare the rudimentary artistic

philosophy of Lorelei Shannon to the visions of Peckinpah or Kubrick, but

then I’m never, ever directly comparing good video games with good movies in

general, either). And, for that matter, out of all video game genres, this

particular sort of experience, even in pure theory, can only come from the

adventure game — or, at best, an RPG which places much more emphasis on plot

than combat or character leveling. Of course, whether that’s a good or a bad

thing is up to you to decide for yourself. |

||||