|

|

||||

|

Studio: |

Sierra

On-Line |

|||

|

Designer(s): |

Jim

Walls |

|||

|

Part of series: |

Police

Quest |

|||

|

Release: |

November 1988 |

|||

|

Main credits: |

Programming: Robert Fischbach, R. E. Heitman, Chris Hoyt et al.

Music: Mark Seibert |

|||

|

Useful links: |

Playthrough:

Complete

Playlist Parts 1-5 (305 mins.) |

|||

|

There is not a lot of information circulating around concerning

the making of Police Quest II,

which means it must have been a pretty routine affair on the whole. Given how

boring the first game in the series must have seemed to many Sierra fans even

at the time of its original release (to be fair, I am inferring this

statement rather than basing it on any objective statistics), it is a little

curious that the series managed to persist — but perhaps more curious, and even more of an honor to the «Sierra way of

life» at the time, is just how far it evolved over a mere one year separating

the Christmas season of 1987 from that of 1988. For sure, Sierra was entering its Golden Age at the time: with

several years of accumulated experience happily multiplied by technological

process, allowing for better graphics, richer sound, and more detailed

content, all of Sierra’s classic

franchises — King’s Quest, Space Quest, Leisure Suit Larry — were becoming more exciting and mature than

they used to be, and Police Quest

was no exception. The second game in the series is arguably the best not

because its creators were suddenly struck by collective lightning, but simply

because the time window was right to produce the best possible adventure

games of all time. However, even in that time window success was not

automatically guaranteed; involving storylines and appealing game design

hardly ever came down from the sky wrapped in pink ribbons, and one need only

try to immerse oneself in the wretched experience of Codename: Iceman to understand that decisions which did work in a certain setting (police

work) began to backfire and come out all wrong in another (secret agent

stuff). So

let us give credit where it’s due: Police

Quest II set a certain quality bar for the series which it would be

unable to surpass in the following years, and we do have to personally thank

Jim Walls and Mark Crowe for that. The game not only took dutiful advantage

of technical progress — introducing actual music to the series and improving

the graphics — but it also gave the story of Detective Sonny Bonds a bit more

direction, purpose, and personality. While retaining the overall focus on

«proper police procedure» and even further tightening it in some areas, Police Quest II differed from its

predecessor by having an actual plot, which begins to unwind itself right

from the start of the game; it also gave its playable character more, uhm, character by surrounding him with

buddies and loved ones. Last, but not least, it achieved a decent balance

between puzzle-based and dexterity-based arcade challenges... and it didn’t

have poker, which is always a plus. As

one of the first games to be made with the use of Sierra’s SCI engine, Police Quest II was somewhat

overlooked upon release by the excitement and admiration over King’s Quest IV, getting, I think,

fairly perfunctory, «coldly positive» reviews from most gaming magazines.

This is understandable; next to the colorful fantasy world of King’s Quest, and particularly next

to William Goldstein’s magnificent soundtrack, lilting out of all the brand

new Sound Blasters and Roland MT-32’s, the world of Police Quest remained fairly drab and underwhelming in

comparison. With so many new opportunities opening up to depict beautiful

fantasy universes, who really wanted to see all those resources wasted on

immersing you in a digital projection of that very real universe from which

you were trying to escape in the first place?.. However,

in retrospect, as digital fantasy universes began piling up like pancakes and

games taking place in the «real world» became perceived as a rare commodity, The Vengeance gradually came to be

almost universally regarded as the highest point in the Police Quest saga — which, admittedly, is still not too high on

the overall scale (it still comes out as the best Police Quest game even, for instance, in this somewhat screwed-up

PCGamer

ranking of Sierra games, conducted by someone whose views on what makes a

great game are barely compatible with mine, and who, for that matter, clearly

has a hard time understanding the meaning of the term "gung-ho"). In

the following sections we shall take a look at its various aspects and try to

understand what it is that makes even an occasional cop-hater reluctantly recognize

the intrinsic value of this experience. |

||||

|

Content evaluation |

||||

|

Unlike the first game in the series, the second Police Quest gives you fairly little

time to get adjusted to the sight of Lytton’s new EGA-era looks before an

actual story takes off — literally minutes after you, as Sonny Bonds, now

promoted to Homicide Detective, step inside your office within the renovated

Lytton Police Department building, the big news arrives on the scene: Jessie

Bains, the «Death Angel» whom you so smoothly put behind bars in the previous

game, has escaped from jail and is on the loose again! Furthermore, instead

of choosing to lay low and bide his time like sensible criminals usually do,

the first thing he’s put together is a list of people responsible for his

capture and conviction, each one of them having received a death sentence

from the guy. Apparently, he’s not just

a dangerous drug dealer, but also a cunning psychopath, and it will require

all of Detective Sonny Bonds’ wit, strength, and courage to (fail to) prevent

a string of executions and rid Lytton of its biggest danger, once and for

all. If the first game was really all about trying to simulate an

urban environment and recreate the banality and boredom of a routine cop’s

everyday duties, only occasionally spiced with amusing details or a hint of

some unique adventure, then Police

Quest II pretty much dispenses with all that stuff, instead offering the

player a concise and generally realistic (with a couple major exceptions,

which we will get to a bit later) detective story. This time, you do not get

to aimlessly cruise around town; there is not even an actual map, just a set

of disconnected locations where you go from Point A to Point B simply by

getting inside your car and typing "drive

to the airport" or "drive

to the mall". There are occasional «mini-side quests» – some of them

optional, some not – that may detract you from your main goal, but the major

emphasis is always on the main task: track down the itinerary of Jessie

Bains, collect all available evidence, and deal out the ultimate justice. What does remain largely unchanged from the first game is the

lack of any «sensational» twists. To a large degree, this is still a game about properly sticking

to police procedures and ensure the safety of both yourself and the

surrounding citizens, rather than about thinking out of the box — although

this time around you actually have to do some thinking in order to beat all

of the game’s puzzles and collect the maximum available amount of points,

rather than simply having to carefully read through the accompanying game

manual (well, you do still have to

read the manual). Like its predecessor, the game is split into a linear

sequence of mini-sections: you arrive at a certain location, clear it out if

necessary, scoop up as much evidence as possible, get a clue or two about the

killer’s next move(s), move to the next location, rinse and repeat. Fortunately, the locations are varied enough, both visually and

in terms of what to do about them — you will have to engage in some

underwater diving, learn how to properly dismantle a booby trap in a motel

room, and get your bearings inside a twisted set of sewage tunnels clogged

with methane pockets, among other things; nothing too unrealistic, but nothing

too mechanical and repetitive, either. Unfortunately, the worst thing about

the plot is that it is almost completely linear, and no matter how thorough

and meticulous you are, you won’t be able to prevent even a single murder or

kidnapping — all you can hope for is reaching that coveted «300 out of 300»

result at the end of the game. This was a serious drawback in the original

game and it remains the same for the sequel: I mean, if all this strict

following of proper police procedure does not

result in actually saving more lives, why bother at all? Wouldn’t it be

easier to just go the Clint Eastwood route or something? Most of the actual «choices» you get to make in the game just

lead you to gaining or losing those extra points; at best, you can choose, for

instance, whether or not to follow the bad guy on a plane to Houston (but

you’ll never make the trip even if you do

choose to fly), or whether or not to squander all your money before a

restaurant date with your sweetheart, which results in either your going home

with her after the date or staying behind to help wash the dishes to cover

for your check. (Big frickin’ deal, since you don’t even get to see what

happens at home after you leave the restaurant...). And most of that pile of

evidence you collect will simply end up rotting in the vaults anyway, so... Then there are those occasional «detours» from the main quest,

some of which are short, simple, and okayish (like arresting a mugger or

offering psychological aid to a colleague at work); however, the biggest one,

in which you have to defeat a bunch of terrorists who foolishly try to hijack

your plane ride, is really

distracting and stupid, not to mention vaguely offensive (the hijackers are,

of course, Arabic guys in headscarfs demanding "safe passage to their desert home of Bum Aroun, Egypt"

"in the name of The Sheik Of The

Golden Sands!"). I mean, if this were some absurdist comedy game, Police Academy-style or whatever, this

would have made some sense, but with Jim Walls’ constant appeal to realism this

entire sequence feels like it’s been treacherously implanted inside the game

from some other project, and this sucks. (It’s actually much closer in spirit

to the atmospheres and attitudes of Jim’s miserable failure of Codename: Iceman, presaging all the

silly clichés and tropes of the «secret agent adventure» genre). Even

the sequence where you have to find and disarm the bomb left behind by the

hijackers feels contrived and utterly dumb next to the regular

policework-related events of the game. Still, there is no denying that the game at least keeps you on

your toes and somewhat intrigued — now that your own life is actually on the

line, as is the life of your girlfriend (and this time around, the entire

romance line is handled just a teeny bit better than in the previous game), Police Quest II gets a darker, more

serious tone, bringing it a little closer to the actual feel of a police

movie. Oh, did I mention that you actually get your own cop buddy this time?

He doesn’t do much, other than chain-smoke his way around you, offer a

wannabe-funny quip or two, and having to make you wait every time you need to

leave a crime scene because he takes so much time to move his legs across the

screen — but how could a computer game about cops ever hope to compete with Miami Vice without a proper partner

angle? |

||||

|

Just as it was with the first game, the hugest challenge here is

not beating the game — to a large degree, the game really plays itself, as

most of Sonny’s basic actions are pretty much self-evident: go from one crime

scene to another, snoop around, then wait for Dispatch to provide you with a

new location, rinse and repeat. There are maybe two or three moments in the

game when you can get stuck if you miss a crucial piece of evidence (like an

address or a phone number), but in most cases, even if you miss it, there

will be someone else, like one of your cop buddies, to pick it up for you

anyway. If all you really want to do is to see your protagonist and his

girlfriend happily flying away into the sunset at the end of the game, Police Quest II is really one of the

easiest titles in the Sierra catalog. The real challenge, of

course, is not to simply beat the game, but beat it with a perfect score. To

do that, you have to work quite a bit indeed, not to mention work around the

classic Sierra parser, which is significantly more difficult than working

with a point-and-click interface — especially since Police Quest II arguably features one of its most highly evolved

versions (that’s not really saying much, merely to point out the fact that

the parser was very much alive and

evolving at the time, gradually getting better until the point-and-click

approach nipped it in its beautiful bud). The trick is not only to go on

sticking to proper police procedure at all times, but also to be as

meticulous as possible in your investigation. Miss a hidden spot, like an

inconspicuous rock at the bottom of the river or a toilet stall at the

airport, and you miss some evidence (minus a bunch of points) which you could

have later booked at the station (minus another bunch of points). Fail to

bring out your camera or your blood sample kit, and you miss even more

evidence. Getting all of it right on the first try without a system of hints

or a walkthrough is practically impossible, although, in all fairness, all of

the actions you have to perform are reasonable and logical — Jim Walls had no

time to mess around with absurd solutions to realistic situations. Only a very few puzzles are not in any way related to your

policing, such as the «romantic» options to sweeten up your date with Sweet

Cheeks Marie, or a situation at the Department where you can offer a

colleague some psychological help (that

one is most tricky, since the game drops no hints whatsoever that you can

even do it — you have to take the initiative in your very own hands). There

are also things you have to constantly keep track of, like having your gun

sights properly adjusted at all times (as far as I understand, it is really

only significant for the final firefight, but forget to do it and you’re dead

meat anyway, instead of newly-wed material); fortunately, at least you no

longer have to perform the «prescribed walk-around safety check of your

vehicle» from the first game — I guess the Lytton PD must have relaxed regulations

somewhat in between 1987 and 1988, what with so many police officers wasting

away so many man-hours walking around their vehicles instead of arresting

criminals and such. Unfortunately, Murphy’s Law

states that «eliminating one dumb, annoying option shall always be compensated

by introducing another dumb, annoying option» — in this case, you are

burdened down with your field kit which you always have to take out of your trunk at each crime scene and always put back before leaving the

scene. I mean, really? You have all

that huge inventory of evidence on your body at all times and you can’t allow

yourself to add a tiny camera and a fingerprint kit to what you’re already

carrying? Plus, it wouldn’t be so bad if you didn’t have to align yourself 100%

with that tiny pixel position «next to the trunk», which can actually be

tricky even when playing at slow speed... In any case, on the whole the puzzle system is still an

improvement over the first game. At least in here you actually get to do some

investigative work, and are occasionally — very rarely — prompted to engage in some creative thinking, like,

for instance, having to revert the «bomb-building» instruction to a

«bomb-disarming» one on the airplane (not that this is in any way difficult,

but at least it mildly stimulates your brain with a 100% certainty of being

rewarded for it, unlike those stupid poker games in Police Quest I). And, like I said, the parser really helps

building up more of a challenge, with the game recognizing an impressively

large number of nouns (corresponding to surrounding objects) and giving you

plenty of predicted opportunities for making the wrong choices. In the end, the

important thing is that playing Police

Quest II almost never gets proverbially «tedious» — except for that

goddamn field kit — and this is probably the highest compliment one could

ever issue to a Jim Walls-designed game. |

||||

|

Strange as it seems, and in an almost unprecedented situation

for Sierra’s Golden Age, the effect of immersion

feels seriously weaker in Police Quest

II than in its predecessor, despite all the technical and substantial

improvements. Each time I play the game, I feel more like I’m just there to

solve the criminal puzzles and get myself out of a tight situation rather

than to experience the sounds and sights of a realistic-but-fictional

universe. I quite explicitly blame this, first and foremost, on the sense of

total disconnection between all the

locations you visit. Sure enough, by eliminating the City Map feature Walls

and Co. may have saved you an hour or so of tedious driving, but somehow they

also ended up eliminating the organic and connected feel of an actual city.

This may have had to do with the same technical factor that also determined

the structuring of Leisure Suit Larry

II — since the game’s content had to be divided between multiple floppy

discs, each one was allocated to covering one or two locations. But what sort

of worked for Larry, where the

game’s travelog philosophy implied that you had to say goodbye to one city,

island, ship, or plane before moving on to another, hardly works for a game

most of which takes place within one city only

(except for the final part). The mini-locations themselves are nicely detalized, with plenty

of environmental knick-knacks and occasional bystanders with whom it is

possible to briefly interact — even including an occasional Easter egg, like

meeting Larry Laffer himself, waiting for the next plane to rescue him from

being pursued by Dr. Nonokee’s henchwomen. However, the feel is typically

perfunctory: each place feels structured as primarily a «police challenge»,

with all the detalization intended to make you feel lost in a sea of red

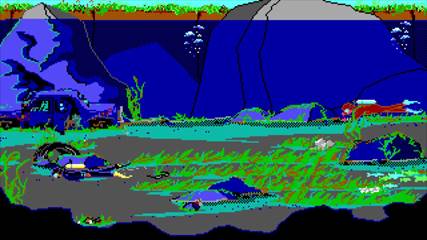

herrings, with a clue or two scattered among them — literally so when you have to scavenge at the bottom of the

river, separating the mountains of chaff from a few valuable pieces of

evidence, not to mention that you only have a limited amount of air in your

tanks, so you don’t exactly have time for a lot of sight-seeing. Nor is there, at almost any point in the game but the very last

part, a genuine sense of suspense and danger. How could there be, if most of

the time is spent by you either at the Police Station, or investigating crime

scenes from which the actual criminal has long since departed? Even the silly

plane-hijacking scene, due to its very silliness, feels parodic rather than

suspenseful. Only when you get to the last part — tracking Jessie Bains,

one-on-one, through the sewer system of Steelton, with its grimy graphics and

sinister music — do you get to experience anything even remotely close to

actual tension (which, admittedly, is still one moment too many when compared

to the first game, where the most tense situation consisted of you playing

poker with a bunch of gangsters). Yet, once again, I am not prepared to blame

Jim for this lack of Hitchcock moments, what with the very point of the game

being in modeling a situation close to real life. I am prepared to blame

him for failing to make this real-life simulation wholly believable, involving,

or exciting, though. The game’s only «romantic» interlude, for instance,

which brings our hero together with his girlfriend on a restaurant date, is

generic and corny — apparently, it is supposed to make us «care» about Sweet

Cheeks Marie, developing a little empathy for her prior to her being

kidnapped by Bains, but the entire scene, including the preparations (buying

flowers, etc.), feels like it was loosely adapted from an English textbook

for foreign students ("I’ll have

the lobster", "thank you

very much sir, your order will be ready shortly", that sort of

thing). We don’t even get to have a close-up shot of the two lovers, much

less an opportunity to follow them after

the restaurant date... somebody get Al Lowe in here, pronto! Speaking of Al Lowe, most of the attempts at humor in Police Quest II show that Jim Walls

has an even more serious problem in this department. Jim’s idea of a joke is,

for instance, to have an allegedly attractive blonde girl standing with her

back behind you in the airport’s waiting room — if you try to start up a conversation

with her, however, «she» turns around and, lo and behold, it’s a

long-haired blonde guy with a

beard, har har har. There’s also an endless stream of annoying, unfunny jokes

on his own smoking that your partner Keith peppers you with while driving,

plus a bunch of safe, boring, predictable «police humor» back at the station

which may be realistic, but probably does not even compare to Miami Vice standards, let alone

anything higher up on the evolution scale. Well, that’s pretty much how it

was in the first game, too. Naturally, not every adventure game is supposed to have a lot of

atmosphere to be playable and enjoyable; but given the generally outstanding

achievements of Sierra in that respect with the arrival of their SCI-era

strategies and technologies, Police

Quest II is a noticeable disappointment on this front when lined up

against King’s Quest IV, Space Quest III, Hero’s Quest, Conquests Of

Camelot, or, well, just about any other Sierra game in the 1988-1990

«Golden Age» — the real reason why

the series is remembered with less love than the others, not the artificially

thought-up «cop-a-ganda» bullshit. It’s just that, yeah, we get it, real life

does tend to be kinda dull, and the general people you meet in real life do

tend to often conform to stereotypes, but this is precisely what we have art

for — finding a good balance between ordinary realism and interesting human behavior, none of

which finds any representation in this game. |

||||

|

Technical features |

||||

|

As a proverbial late-runner at just about every turn in Sierra’s

history, Police Quest II had no

visual innovations of its own that would not be inherited from the earliest

games of the company’s early EGA / SCI era. Cheryl Loyd and Vu Nguyen, responsible for all the

backgrounds and animations, were not among Sierra’s list of top graphic

artists, and what they do is credible, reliable work without a lot of grounds

for admiration. In fact, I think that they might have even overdone it in

places: when it comes to landscapes, for instance, they are a bit too eager

to take advantage of the increased graphic resolutions, peppering their dust

roads and tree branches with too many pixels of too many different colors,

instead of keeping it relatively sparse — the effect is that the backgrounds

feel a little too «messy», particularly on modern monitors, when compared to,

say, Mark Crowe’s graphics in Space

Quest III. This is particularly bothersome when you shift from the

aesthetic angle to the pragmatic one — like, for instance, trying to find tiny

useful bits of evidence at the bottom of the river; your eyes end up straying

in all directions, and the inability to keep focused combined with being seriously

strapped for time ends in genuinely undeserved frustration. And

speaking of pragmatic, with the entire game so tightly focused on

investigation of crime scenes and little else, I don’t think the artists were

even bothering with the goal of visually entertaining their audiences. What

few efforts there are to convey a bit of beauty through eye candy — like, for

instance, all the intricate flower arrangements in Steelton’s city park — are

few and far in between, and Sonny Bonds, Homicide Detective, does not really

have the time to stop and smell the flowers anyway (of which the game informs

you explicitly whenever you try to take a break from your work). That said,

the amount of realism and detalization still has to be commended: the

directive was not to make the game look particularly «pretty» or

«intriguing», but to make it look relatively close to real life, and the

artists did earn their salary. The airplane does look cramped, and the police

offices do look cluttered, and the sewers through which you have to chase

Bains for the last minutes of his life (or your life, if you play it badly) do look dirty and dangerous, and

even smell kinda funny. One

thing the artists weren’t apparently too hot on are close-ups: there is one

of Sonny and Keith in the car, sitting with their backs to you, and another

real ugly one of Sonny talking to his boss if he takes too much time with his

tasks, and that’s pretty much it. Several rather ugly small-size profiles of

characters talking on the phone show that Cheryl and Vu did not really have

the talent of Mark Crowe or Doug Herring when it came to using EGA pixels for

portraying people — so perhaps it was wiser that way, except that in the

aftermath we do not even have a proper visual representation of Sonny’s chief

nemesis (Jessie Bains) or Sonny’s soon-to-be-wife (Sweet Cheeks Marie). Quite

a bummer for those of us who’d like to form an internal bond with Sonny Bonds

and use him as a role model! |

||||

|

Sound At least in this department some progress had been made: where

the first game featured next to no music, other than the main theme that

sounded like a funereal outtake from King’s

Quest III, Police Quest II

features a short, but representative original soundtrack — which was actually

the debut experience for Sierra’s new composer-in-residence, Mark Seibert,

who would go on to write something like 90% of Sierra’s recognizable music,

from the cheesy horrors of ‘Girl In The Tower’ to the impressive Gothic

stylizations of Phantasmagoria.

His occasional schlockiness and lack of taste aside (I mean, the man had

spent eight years playing in a Christian rock band, what do you expect?),

there is no denying the man’s talent or versatility: the music of Police Quest II, in particular, has

an easily recognizable Miami Vice-style

1980s police-soap synth-pop flavor, and the main theme to

the game even manages to be kinda catchy, with these funky MIDI horns and

all. Although the total amount of music written for the game barely

surpasses 10 minutes, it is responsible for almost 100% of its atmosphere —

it is, for instance, the thirty-second long ‘Underwater Theme’, combining a

little mid-Eastern flavor with a little Western minimalism, that produces the

impression of briefly passing into another dimension of existence, rather

than the encumbered visuals; and it is the fourty seconds of ‘Marie’s

Kidnapping’ that manage to introduce a little compassion and humanity into

the tragedy of Sonny’s girlfriend being abducted by Bains, rather than the

non-descript visuals and the bland accompanying dialog. There’s a happy,

fast-paced vaudeville theme to reward us after the bad guy has been dealt

with, and a little variation on Mendelssohn when Sonny finally proposes to

Marie — which helps make the game’s epilog a little more rewarding and even

re-watchable after the disappointing conclusion of the first game. None of this is particularly smashing — certainly nowhere near

the visionary effort that was William Goldstein’s soundtrack for King’s Quest IV — but as a first

serious try for a fresh new composer, it’s credible work. There may have only

been about 10 minutes of it altogether, but in these 10 minutes, Seibert

managed to prove his worth in gold to Sierra. Synth-pop, ambient, funky, lounge-jazzy,

rocking, vaudeville — he’s done it all here; no wonder he would go on to be

employed regardless of the particular genre of any future Sierra game, be it

the fantasy of Quest For Glory,

the pseudo-history of Conquests,

the Gothic horror of Phantasmagoria,

or the smut of Leisure Suit Larry. |

||||

|

When it comes to playing style, Police Quest II is probably the most «adventuresque» game in the

entire franchise. With the elimination of the city map (a questionable

decision) and no poker tables in sight (a joyous decision), there is barely a

single moment in the game when you have to rely on nimbleness, agility, or

sheer pot luck so as to achieve your goals. Even the shooting range, which is

absolutely not optional in this

game (miss it and you die, fair and square), functions more as a puzzle (an

annoying one, but still a puzzle) than an exercise in training your eyesight

and finger reflexes. A few of the sequences are time-dependent, as you can

run out of air at the bottom of the river or fail the quickdraw test during

the final showdown, but this is really not a big challenge for even the

sluggiest of players. Again, this approach may have been intentional — to

show you, symbolically, that you don’t have to be a real sharp shooter or in

great physical form so as to be a good cop, as long as you have your head

firmly placed on your shoulders... and stick to those rules at all times, of

course. This does mean, however, that Police Quest II essentially just relies on the most standard

version of Sierra’s Creative Interpreter engine and little else. Other than a

few function key shortcuts for drawing and firing your gun, etc., you always

type in whatever you have to do — and, as I have already said, the parser is

fairly well advanced here, recognizing quite an impressive array of synonyms

and even some short phrases; you won’t be getting much out of this, but the

game does sort of invite you to experiment creatively. For instance, while

passing by the completely insignificant pond in the park, you can type in

"feed the ducks" and be told that you cannot feed the ducks. Sure

you knew that, but it somehow feels nice to be able to try and learn that the

game designers preemptively thought you might try to go that way.

("Catch the ducks" will get you a response of ‘planning a barbecue while your girlfriend’s kidnapped?’, which is

even more touching). One thing the game could

have benefited at this point would be the addition of a hint section, at

least post-game, the way it would soon be done for The Colonel’s Bequest; there are so many things that can easily

be missed, either by failing to properly decipher the pixelated clues on the

screen or by not coming up with the right idea of what to type in the parser,

that having Sonny’s captain or somebody else patiently explain to us at the

end why we are so far away from the coveted 300 points would have been nice.

Supposedly, however, a pretty big part of Sierra’s revenue at the time came

from selling hintbooks; also, since most of these missed points come from non-crucial

activities, it’s always easy to say that anybody who wants to be a top dog

really has to work for it, right? Don’t be a snowflake and all, that sort of

thing. At least back in 1988, when relatively few people had computers and

most of those who had were willing to blow a shitload of time on the latest

adventure game on the market, it might have made sense. |

||||

|

To be honest, I really don’t know what to make of this game.

It clearly tries – and occasionally comes close to succeeding – in taking

itself more seriously than the first Police

Quest, both in its attention to detail and in framing its challenges with

more elements of suspense and deadly realism. It tries to push the player’s

imagination in more diverse directions with its creative use of the parser.

It manages to seriously reinvent the established formula while at the same

time keeping its essence intact (proper police procedure should be obeyed at

all times!). And yet, it still cannot save the series from being a little... wooden, I’d say, next to its livelier

competition from other Sierra artists. The characters remain stereotypes, the

plot remains minimal and rather silly, the humor is largely funny just

because we laugh at the very idea of trying to include humor in a game like

this one, not because of the actual jokes or comic situations. In the end, it’s still

a relatively well-made game whose worth has, perhaps, increased as time goes

by, largely for historical reasons — being one of the few «reality-based»

adventure games produced in the late Eighties, it gives you about the same

perspective on the mores of the

times that you get from rewatching soaps from that era, only through a

funnily distorted lens of 16-color EGA and the relatively simple mind of a

retired police officer. You know — those happy innocent days when airport

security was nowhere near as tight as today, and the lobster was $16.00 at the

restaurant, that sort of thing. (I guess this sounds even more escapist, in a

way, than talking about unicorns and flying saucers!). If only that world

around Sonny Bonds were more detailed, and 99% of the game did not have to

revolve around chasing the Death Angel, it could have the potential of becoming

an invaluable time capsule. As it is... well, let’s just say you’ll probably

only enjoy it if, like me, you have an inborn attraction for the Sierra

On-Line gaming philosophy. |

||||