|

|

||||

|

Studio: |

Sierra

On-Line |

|||

|

Designer(s): |

Jim

Walls |

|||

|

Part of series: |

Police

Quest |

|||

|

Release: |

1991 |

|||

|

Main credits: |

Lead programmer: Doug Oldfield Music: Jan Hammer |

|||

|

Useful links: |

Playthrough:

Complete

Playlist Parts 1-6 (321 mins.) |

|||

|

Much like the second Police

Quest game, circumstances surrounding the creation of the third one are

not exactly the stuff of legend — arguably the most notable bit of trivia

here is the sudden departure of Jim Walls, the series’ creator, from Sierra

before the game was even completed, which is a bit ironic considering how much

of Jim you are actually going to see this time around (he pops up every time

you die, mentoring you on the exact details of your alleged stupidity).

Allegedly, they had to bring in an extra writer to complete the game, and

that writer happened to be none other than Jane Jensen, in her first serious

stint for Sierra — I have no idea which parts of the game she is responsible

for, but something tells me that maybe the entire «occult Satanic cult» bit

might have come from her mischievous twisted mind, with the pentagrams and

chicken blood and stuff presaging a similar motif in Sins Of The Fathers... then again, maybe not. All I know is, Jane

Jensen would have looked pretty hot in a police uniform back in 1991, so it’s

kind of a bummer that you still always have Jim Walls guiding you into the

next world whenever you die. Couldn’t they at least have shared duties on

that one? On

a more serious note, precise circumstances leading to Walls’ departure from

Sierra remain obscure. Ken Williams does not even mention Jim in his book;

interviews with the retired police officer are scarce and largely avoid that

topic; and second hand sources mostly just suggest that Walls was becoming

dissatisfied with how things began to be run at Sierra, which in the early

1990s was beginning to behave like a serious business corporation instead of

the friendly, scruffy get-together that it still was in the 1980s — a feeling

I could certainly get behind if it were true. Not

that, of course, Jim Walls was some sort of easy-going, attention-shunning

creative genius, extinguished by the rise of the corporate approach in the

gaming industry. His only non-Police

Quest game during the several years he spent with Sierra was Codename: Iceman, an absolute flaming

disaster that illustrated how just about everything

in an adventure game could go wrong; and the alleged «gritty realism» of the Police Quest games was not exactly

supported by genius writing or innovative puzzle design, either. Yet there

was certainly something wholesome and charismatic about the man’s attitude

and work spirit, and it is now clear that his loss of interest in his own

creation and subsequent departure was one of the first, if not the very first warning bell for the

future of Sierra On-Line and even «old school adventure gaming» in general.

On the whole, Sierra’s transition from its «Golden Age» of the late Eighties

into the «Silver Age» of the early Nineties went fairly smooth — no doubt,

due to Ken Williams’ extraordinary managerial and scouting talent — but

events such as Walls’ departure illustrated fairly well that the atmosphere

was already changing, even if no single individual could be blamed for that. That said, if we decide to stay on the surface

rather than scratch our way deep inside, everything seemed to be on the

upturn. With technological advances leading to breakthroughs in digital video

and audio, Police Quest III was

the first game in the series to receive a brand new coating of hi-res VGA

graphics, a full-on musical soundtrack commissioned from a professional

composer, and even an entire set of rotoscoped real-life actors adding

another realistic layer to the game (unfortunately, the budget was still too

thin to allow for actual voice acting — it took Sierra at least another

couple of years to begin including voice acting into all of its titles). This

way, even if parts of the story seemed like they were simply remade from bits

and pieces of earlier games (see on that below), the psychological effect was

so different that fans and reviewers alike remained pleased — even if I do

not think that the game could have earned Sierra a major new bunch of fans. In retrospect, of course, as the many technical and

designer innovations of Police Quest

III grew dimmer and dimmer, nobody cares all that much about the last

chapter in the exciting, but stereotypical life of Officer Sonny Bonds — at

most, the game is briefly discussed in the overall context of the legacy of

the Police Quest series, and as a

stand-alone title, I think that it’s even been overshadowed by the VGA remake

of the first Police Quest game

that came out in 1992. So it falls to us now to put the game under the

proverbial microscope and see whether it could still be of any use to the

modern retro-gamer. |

||||

|

Content evaluation |

||||

|

Regardless of who precisely was responsible for the bulk of the

game’s plot — Jim Walls, Jane Jensen, or somebody else who went uncredited — Police Quest III suffers from a

fairly strong case of sequelitis.

The first two games played off each other nicely in that Police Quest I was all mostly about the routine struggles of a

cop trying to keep up with complicated police procedure by walking around his

vehicle and reciting Miranda rights, while Police Quest II was more of a straightahead thriller, focused on

murder and detective work. They had plenty of things in common, but on the

whole, the two games looked and felt as different as the color of Sonny

Bonds’ hair, changed from black to blonde for no reason at all other than to

remind you how much the world at large has gone through in less than two

years. Not so with Police Quest

III, whose first part essentially reads like a remake of Police Quest I, and whose second part

has more parallels with Police Quest

II than you could shake a nightstick at. At the beginning of the game,

your main hero, Officer Sonny Bonds, despite having recently been promoted to

Detective Sergeant in the Homicide division, has apparently been "assigned to Traffic Division for a bit...

overburdened as the department is". The real reason for this re-assignment is, of course, that Jim and

Co. want you to refresh your memory about what it means to be a routine

patrol officer — writing out speeding tickets, arresting drunk drivers, sorting

out highway trouble in more or less the same ways you already did that stuff

back in 1987. This sort of «anti-plot» can theoretically work if it’s done

right — as it was in the first game — but, unfortunately, the way it’s done

in Police Quest III is far more

draggy, which I shall try to explain more in the «Atmosphere» section. Then, at the end of your first day at work, something terrible

and totally life-changing happens right outside of your reach: a couple of

bad-looking Thugs (with a capital T) daringly ambush and assault Sonny’s

totally innocent wife, Marie Wilkans Bonds, right inside the parking lot of

Lytton’s mall, stabbing her with what looks like a pen-knife for no apparent

reason other than general misogyny (or a serious psychotic allergy to late-Eighties

women’s hairstyles). Fortunately, they somehow just end up putting her in a

coma for several days — but now Sonny has larger fish to fry than speeding

violators, as he is immediately reassigned to Homicide and put on his wife’s

case. Here, the game turns into Police

Quest II, with our hero having to do serious detective work once again,

trudging along a suitcase of police tools and investigating a sinister occult

organization that keeps murdering people to the left and right, while all

poor Sonny is able to do is diligently scrape out clots of blood and skin

from under their rigid fingernails. It is almost certain that Jim and the boys were quite

consciously aware that they were merely putting a slightly different twist on

the events of the first two games this time — and that the underlying idea

was to simply take everything that was (or at least seemed) good about those

games and remake it on an entirely new level of technology, with better

graphics, better sound, more realistic and detailed dialogue, and more, umm,

psychological depth or whatever; in other words, more or less the same line

of reasoning that would justify the existence of Grand Theft Auto V a quarter century later. One might have

reasonably objected that, perhaps, it would have simply made sense instead to

remake the first two games in better quality, while still striving to make

the third title have a personality of its own — and, bizarrely, Sierra

partially did that just as well,

releasing a remade version of Police

Quest I less than a year after The

Kindred, which, hooray and hooray again, means that you now have not one,

but a whoppin’ three different ways

to administer the Field Sobriety Test to a drunk driver. Struggling to think what it might actually be, plot-wise, to at least

somewhat individualize The Kindred,

I can think of but two aspects, neither of them particularly beneficial. One

is the decision, after five long years of deliberation, to introduce the idea

of police corruption — in the first

two games, just about everybody in Lytton’s PD, from top-ranking officers to

the lowly patrol officers, were as clean as a newborn baby’s ass, and the

worst thing one could find about any of the men in blue was an occasional fit

of grumpiness or an atrocious sense of humor. Now, finally, Jim Walls has

acknowledged that there may be one

or two bad eggs in the Department from time to time — though, of course,

hardly on any of the top levels. The scapegoat chosen for the task happens to

be (spoiler alert!) Sonny’s partner Pat Morales — a decision that, in today’s

world, should only result in heaping accusations of both racism and sexism on poor Jim Walls’ head, though back at

the time I don’t think anybody really gave a damn. But even if the bad egg in question were to be a white guy

instead of a Spanish-American girl, the portrayal would still remain

grotesquely unbelievable, because Pat Morales is depicted as (a) rude, crude,

and insubordinate, (b) psychotic and offensive in dealing with potential

violators, and (c) downright criminal

by the end of the game, capable of shooting you in the back if you don’t get

to her first. The idea of putting all

those bad eggs in one single basket would probably not have occurred to even

the creators of the cheapest and silliest police TV dramas. I mean, pure

logic dictates that either you are

rude and disobedient to your superiors or

you secretly pilfer packets of cocaine from the evidence lockup, not both of these things at the same time,

right? And if Lytton PD can really afford to continue to keep Morales on the

job with that kind of evaluation file, things must be really hard for the

department — I mean, she is actually promoted to the status of Sonny’s

partner in the Homicide Department after

he writes up a negative evaluation of her character. Perhaps somebody is

pulling some strings for her at the top level somewhere? Shouldn’t Sonny be

looking into that level of

corruption, then?.. (The irony of the situation is that even with all these features

and circumstances, Pat Morales ends up coming across as a largely sympathetic

character — her rudeness and insubordination just end up establishing her as

an independent, confident lady, and most of the time she’s just hanging

around taking photos, delivering an occasional joke or two, and constantly stalling

Sonny by taking extra trips to the mall in order to phone her bosses. It’s

almost as if they wanted to exonerate her by the end of the game, but then

changed their mind at the last moment due to lack of funding for the

additional purposes of the NPC Redemption Program). The second and even bigger problem is that the game eventually

introduces some sort of Satanic cult into Sonny’s investigation without

giving us the slightest info on what really is its motivation and the reasons

underlying its creation and activities, other than the general mwahaha I am the Anti-Christ pattern.

That the game’s main antagonist and one of the cult’s leaders just happens to be the brother of Sonny’s

primary nemesis of the first two games is, of course, just a fateful coincidence.

«Hey! I can get my revenge on the asshole who killed my bro and bag myself another successful

Satanic killing at the same time, ain’t I just the luckiest bastard on

earth?» This disastrous decision to tie together two disparate threads

(revenge and Satanism) pretty much castrates the plot — and thus a game that

was honestly supposed to push forward the darkness and grittiness elements of

its predecessors ends up being far more ridiculously unbelievable than both

of them. It doesn’t help, either, that the rushed nature of the game’s

ending fails to establish the main antagonist as a person of any

significance. At least Jessie Bains was introduced to you at the end of Police Quest I and had a slight

chance to intimidate you before the endgame; then, in Police Quest II, he kept menacingly cropping up at certain points

in the game and had a tense stand-off with you at the end. His brother

doesn’t even get to bump you off himself if you fuck up — any of his minions

has a higher chance of sending you off to the Jim Walls mentoring screen than

he has. It would have been less insulting to the memory of poor Jessie if

they’d just make Michael Bains into some anonymous cult leader, leaving out

the «kindred» angle altogether. Then again, we’re supposed to believe that in

a nice, clean city like Lytton any ongoing crime has to be exclusively

masterminded by members of the Bains conglomerate, sent to Earth in order to

remind the God-fearing population of Lytton that life was never expected to

be a rose garden. Fortunately, we still have people like Officer Sonny Bonds

to prevent the evil dudes from completing their pentagram and turning Lytton

into the headquarters for Satan’s domination of this planet. It is thus quite a good thing that you have to spend so much

time in the game delving into the technicalities of police procedure and

learning by heart Lytton’s street geography — because it honestly takes your

mind off the general idiocy of the plot, concentrating it on better (if

occasionally more frustrating) aspects of the game. I don’t know who is more

guilty of the way things turned out — Jim, Jane, or anybody else working on

the game — but I do know that in

terms of the general story line, Police

Quest III belongs right up there with Codename: Iceman as one of the stupidest things in Sierra

history, and I do believe that it

would have been a much better idea to just leave Jim Walls as a «technical

consultant» on all aspects of the game rather than give him free rein to

convert real-life action into detective fiction. |

||||

|

Arguably the only aspect in which Police Quest III managed to win the upper hand over its elder

buddies are the game’s puzzles — and this is largely because the game has a few of those, period. Police Quest I and II, essentially, were all about you

studying the manual of proper police procedure and stoically applying it

whenever you went. Never once did you really get into a situation that would

require any out-of-the-box thinking, meaning that the most complicated the

game ever got was when you had to do some pixel-hunting to identify a tiny

object wedged in the corner of the screen. Of course, Police Quest

III has that same thing in spades, too; but it also acknowledges — thank

God — that even in the life of the most ordinary, routine-following cop there

comes a time when a non-standard situation arises to which there is no ready

answer in the manual, which is precisely the situation that segregates the

«thinking cop» from the «dumb cop». Right at the beginning of the game, for

instance, you are faced with the task of subduing and securing a deranged

individual causing trouble at a public park — and in order to accomplish this

task without either causing serious harm to the guy or getting clobbered

yourself, you have to adopt a «tricky» strategy. A pretty simple strategy —

even casual adventurers will probably figure it out in a jiffy — but one that

you certainly won’t find in your instructions, and which definitely had no

analogy in either of the two previous games. (According to Jim Walls, the

deranged guy episode was inspired by a real incident that happened to him

during his own policing years — which only makes me wonder why he’d been

saving it up so strictly until the third game in the series). This is quite

an auspicious start to the game’s challenges — although immediately and

seriously offset by the fact that your next

series of challenges is going to be a rather boring rewrite of the traffic

patrol sequences in Police Quest I,

once again totally safe and predictable, unless you decide, for the fun of

it, to shoot a secret agent point blank in the face or to take a pregnant

lady to jail for speeding, and thus end the game prematurely because Officer

Sonny Bonds refuses to be a mindless tool of the police establishment and

would rather be its Angel of Death. Once you finally get into Homicide and start up the

investigation of the attempt on your wife’s life, interesting challenges

slowly begin coming back. You have to work out a way, for instance, to lure a

homeless old lady into the PD so that she can help you identify one of the

killers — problem is, she’s afraid to leave her cart of the usual homeless

stuff unattended, so you’ll have to help her out with that. You have to get

to the bottom of the odd conduct of your new partner, so you’ll even be

involved in a tiny bit of questionable activity, requiring you to do a little

stealing, a little peeping, and even — oh my gosh! — finding a way to

penetrate, unnoticed, inside the women’s bathroom at the station. (No, there

is no Leisure Suit Larry vibe in this game — even less of it, in fact,

than in the first two games, which occasionally put Sonny «in the mood»). You

even have to call upon the supernatural power of love and affection to help

bring your wife back to life — fortunately, by using something that makes

more sense than a rabbit’s foot. You still have to do

everything you did before, though, such as diligently collecting evidence

from the crime scenes, most of which will probably just rot away in the

evidence locker rather than offer any meaningful assistance — but hey,

anything to get a full score, right? (Unfortunately, the game ended up bugged

so the maximum you could always get was 450 out of 460). The only serious

downside to this is that, just as it was in Police Quest II, each time you visit a crime scene you shall have

to open your trunk, open the suitcase inside the trunk, take out all the

tools, use them to collect evidence, then open your trunk and suitcase again,

put back all the tools one by one, close the suitcase, close the trunk, and

drive away. Yes, apparently this is what real homicide detectives do in real

life, but at least it would have been nice to have it all done in one click rather than in half a dozen.

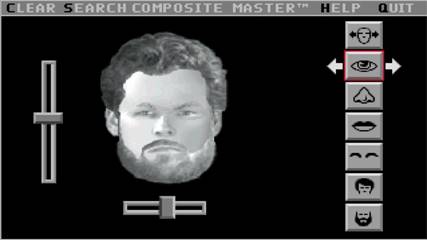

Once again, mock-realism strikes back at you with its dirty claws! Another nice innovation — at least, in theory — is that for the

first time ever you get to use your computer not just as a reference source,

but as an actual working tool. There is a pretty cool (for 1991) piece of

software («Composite Master») that allows you to put together a facial

portrait based on the witness’ description (probably influenced by all those

character-building scripts in early RPG games); and a plotting device

attached to the city map that allows to search for patterns, something that

would be significantly perfected by Sierra almost a decade later with Gabriel Knight 3 but already works

here, though only once and in a very rudimentary form. Although the

implementation of both these algorithms is somewhat crude (particularly the

city plotting tool, where it might take a while to figure out how to use it

correctly), it sure feels like progress. At least the taxpayers’ money isn’t

merely wasted on electronic devices that just sit around doing nothing, other

than letting you enjoy inside jokes on the private lives of Sierra On-Line’s

employees. Overall, however, the difficulty level of Police Quest III feels decreased in comparison — and this is, to

a large degree, concomitant with the game’s transition from a parser to a

point-and-click interface. The latter does

make repetitive actions a bit less frustrating (mouse-clicking, after all,

takes significantly less time than having to type open trunk, get suitcase,

close trunk all the time), but, as usual, it ends up severely limiting your

choices and making the right ones

usually way too obvious. That said, part of the easiness should also be

attributed to the laziness of the team: the game’s script is rather

pathetically small, and there is nowhere near the amount of attention to

surrounding detail as there was in Police

Quest II. Even on screens where your Look

button can net you different (usually quite laconic) descriptions of various

objects, clicking the Use button on

most of them will simply result in the brief appearance of a red cross —

like, these suckers couldn’t even be bothered to write a «what on earth makes you think you can pick

that up?» generic type of message this time around. As usual, dying is an easy option in a Police Quest game, and the various reasons for dying largely

remain the same — the most common ones being insubordination (fail to treat

Dispatch as your lord and master and you’re dead meat), poor driving skills

(I’ll tackle the game’s horrendous driving system below), highway nonchalance

(every car in Lytton City makes it its goal to run over you whenever they get

the chance), and, of course, lack of self-defense reflexes. Most of the

deaths are reasonable, which kinda makes one sad about the loss of ability to

die from embarrassment upon taking your clothes off at any random public

place in Lytton City (see how cruelly 1991 restricts your freedom when

compared to 1987!). Much worse are the several dead ends that you can run

into — although, admittedly, there are very few intentional ones this time around; probably the only truly

serious bummer occurs at the end if you have not been astute enough to

predict your partner’s backstabbing schtick just as you’re busy bagging the

last of your enemies. At least that dead end

comes across as somewhat deserved; unfortunately, the game’s real problem is

that it had always been and still remains one of the most bugged titles in

Sierra history, so there are a few dead ends you can meet if you simply play

the game not quite the same way as the designers would like you to. For

instance, at one time I got hung up near the end when trying to obtain a

search warrant from Judge Simpson, just because I did not give away Marie’s

locket to her at the hospital — which made the game believe that I needed to

give it to the Judge instead, and then made the Judge get stuck in an endless

conversation loop (!). At another moment, you can put away an important piece

of evidence in the evidence room — and put yourself in an unwinnable

situation because you need it later and there is no way you can get it back (like I said, whatever gets locked

up in the evidence room clearly stays there forever, to rot away until the

end of time). The game does offer you quite a bit of choice — usually a «bad

choice» over a «good choice» — and then it is liable to punish you for your

«bad choices» not by reducing your score or making you die, but simply by

going buggy on you. Looks like a rather clear case of cutting down the budget

for beta-testing to me. |

||||

|

With the transition to VGA graphics and all the technological

advances allowing for increased realism in video games, the designer team of Police Quest III were clearly aiming

for a much more cinematographic experience — if the previous titles were

merely influenced by the likes of Miami

Vice, here the goal was to truly allow the player to put oneself inside Miami Vice, for better or worse. Hence

the use of real-life actors (or, at least, real-life people) for rotoscoping purposes; the presence of cut scenes

temporarily taking the agency out of your hands; the hiring of none other

than Jan Hammer himself, the mastermind behind the music of Miami Vice, to score the game; and a

much heavier emphasis on Guts, Gore, and Grit than the last two times around.

We have already established that the efficiency of all these efforts was

seriously threatened by the weakness (to put it very mildly; some might want to use stronger words like

«retardedness») of the overall plot of the game — but then again, many a time

Sierra’s inability to present a strong plot could be fully compensated for by

the tenseness and emotional grip of the atmosphere (hello, Phantasmagoria!), so perhaps Police Quest III could also be

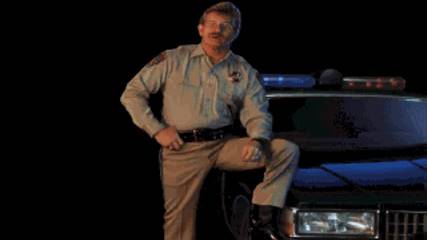

salvaged in the same way? It begins auspiciously enough, with already the opening credits

providing a vast improvement on the perfunctory minimalism of the first two

games — alternating flashing backgrounds of deep blue and dark red, against

which Officer Sonny Bonds keeps pulling his gun on an unseen enemy; later on,

cutting to a dashing image of Jim Walls in his dusted-off police uniform,

striking a pose against a police vehicle and a pitch-dark background, as if

reporting from a scene of the latest crime that happened in the dead of

night... haunting, isn’t it? setting you up for a level of gritty toughness

you ain’t never seen in a computer game before. Then there’s the actual

Police Department — renovated, multi-storied, with added space for a separate

computer lab and a police psychologist office... we’re really moving into the Nineties, aren’t we? Unfortunately, because of the game’s stupid, stupid, stupid driving interface (see below on

that), Lytton City this time around has even less of a feel of a real city

than it had in Police Quest II.

The absolute majority of the locations that you are able to visit consist of

one or two screens of images, typically as devoid of people as possible, and

there is even no possibility to return to most of them once you’re done with

a specific assignment. «Roaming» is essentially limited to the three stories

of your Police Department, and even those get exhausted (and exhausting,

given the need to wait for an elevator all the time) pretty quickly. With the

first game in the series, you actually had a faint feeling of being placed in

an open world-type environment; by the time of the third, it’s all strictly

about the story — and more about Sonny Bonds’ personal vendetta than about

going around normalizing the life of the City of Lytton. The actual «atmosphere», promised by the game’s opening, does

not even begin to materialize properly until the first cut scene which

happens late in the evening of the first day. By the standards of 1991, I’d

say the presentation of the assault on poor Marie Wilkans in the mall’s

parking lot looked fairly gruesome indeed — suspenseful music, dimmed lights,

threatening shadows, close-up of Marie’s terrified face, screaming... yep,

possibly the darkest and most disturbing element in a Police Quest game so far. But, of course, it quickly deteriorates

into generic melodrama, and despite a few tense moments here and there, the

game fails to deliver on the promise of that particular cut scene. We do not

get any more cut scenes dealing with the members of Michael Bains’ crazyass

«cult»; we only get the most superficial look at the game’s deuter-antagonist

before he kicks the bucket, and we get no

looks at all at the main villain (!). And as for the implicitly promised

general «gritty» look at the City of Lytton and its problems, well... ...hmm, well, I kind of liked that bit with the homeless lady,

whose general looks and dilapidated entourage does give the series a tiny bit

of social realism that it completely lacked before — the «seedy» bits of

Lytton City as portrayed in Police

Quest I and II still looked

pretty cute and sunny to me most of the time, while Police Quest III does introduce a few street corners that I really wouldn’t want to find myself on

even in broad daylight. But that’s just about it, I’d say. On the whole, the

team does an almost surprisingly lazy job at making Lytton City an interesting place to immerse yourself

into and explore — compare, for instance, the admirable effort put into

bringing to life the city of New Orleans in the first Gabriel Knight game, which also gives you an assortment of

separate small locations, yet each of these is portrayed with love and care,

rather than merely serves as an indifferent backdrop to the story. Indeed,

despite the general consensus of hatred toward the fourth installment in the Police Quest series, I would

definitely argue that the atmosphere of seediness, danger, unrest, and

overall tension would be pulled off far more efficiently in Police Quest IV than it is here.

There is no doubt that all the superficial advances in technology that The Kindred puts in your face could

make a serious impression back in 1991, but this here is quite a proverbial

case of how technological advances, no matter how sophisticated, inevitably

become less impressive with time when not accompanied by genuine substance.

Unlike the first two Police Quest

games, I believe that this one simply does not have enough heart to keep on

endearing itself to us. |

||||

|

Technical features |

||||

|

The Police Quest

series had never before been anything like the flagman of new developments at

Sierra, so it must have actually been somewhat startling to see Police Quest III, rather than any

other Sierra game, introduce the practice of using live actors — and not to

just project their movements onto the character sprites, but to actually be

filmed and rotoscoped into the game. Although the technology for full-motion

video was not yet ready (Sierra would not go in that direction until four

years later), The Kindred is as

close as they got there by using then-currently available means — that said,

the process must have been pretty expensive, since Police Quest III and IV

were pretty much the only Sierra games for which it was reserved; no doubt,

due to the strong desire to keep this

particular series grounded in as much realism as it could handle. The effort, I believe, was somewhat worth it. The game

characters, when presented in relative close-up, looked stunning back in 1991

— realistic facial features, credible animations, and you even got to see

some of the famous Sierra guys as role models (Josh Mandel, for instance,

makes a pretty believable Leon the Sandwich-Munching Coroner; Corey Cole of Quest For Glory fame is the dashing

police psychologist; and even Ken Williams himself puts in a brief appearance

in the courtroom). Even today most of those close-ups continue to look pretty

decent, though they could all use a bit of remastering. If there is one thing

that gives the game a bit of visual atmosphere, it’s these digital portraits

— and it’s probably a good thing

that those are just portraits, with no actual acting in sight, or even any

voiceovers. Alas, the same good words cannot be put in for the actual

graphic art: here, just as it was in the previous games in the series, the

backgrounds are largely perfunctory and the basic character sprites have the

same general VGA-level ugliness as most of the sprites in this particular era

of Sierra On-Line. In fact, the most striking thing about the backgrounds is

that there simply almost aren’t any

— the few exterior shots that there are, such as Aspen Park, are remarkably

free of interesting details (even less so than in Police Quest II!), and interiors-within-interiors, such as the

individual offices within the Police Department, are given to you as small

cubicles that occupy only the center of your screen, as if this game couldn’t

get any more claustrophobic. True,

visual beauty and scenery porn had always been thought of as way below the

dignity of the respectable Police

Quest player — but a little bit

would have been nice. As such, there is simply nothing to write about in this

section, so let’s just move on to the next one. |

||||

|

Sound Apparently, most of the game’s budget went to the art and

animation department, so Sierra was unable to provide voice acting as well —

as late as 1991, full voiceovers were still a bit of a luxury for the studio,

with Space Quest IV drawing the

lucky straw and everything else put on «mute». It does look a little weird

having to look at Jim Walls all the time, moving his mouth like a fish, but

budget is budget, and frankly, what would be the use anyway if you didn’t

have Gary Owens in your game? (And if you did

get Gary Owens in a Police Quest

game, it’d probably be more like Police

Academy anyway — which might not have been a bad thing, but probably

wouldn’t agree with Jim properly). What Ken and the managing guys did get was probably one of their proudest musical achievements —

nothing less than a whole live Jan Hammer to write a full (well, a fairly

short one) musical score for the game. They’d already worked with noted

professionals, from William Goldstein to Bob Siebenberg, but having Hammer on

board brought them (a) a guy seriously respected in elite musical circles and

(b) the guy who wrote the score for Miami

Vice, and who was, therefore, expected to give the game more

«authenticity» than the rest of the team combined. True enough, if you’re a classic Eighties aficionado and the

harsh industrial synths and processed guitars of the ‘Miami Vice Theme’ still

rock your boat, you might easily love the main musical themes of Police Quest III as well, even with

their glossy MIDI interface (or maybe especially

because of the glossy MIDI interface). With the first game in the series

having nothing but rudimentary beeps and the second one rather lazily scored

by Mark Seibert (also in Miami Vice

style, but with very short and tentative compositions), Hammer’s soundtrack

feels like a real «police symphony» in comparison. The main theme is

multi-layered and catchy, with MIDI keyboards, brass, and guitars giving the

brief two-minute overture plenty of dynamic development; the energetic Patrolling

and Chase themes give you some great Eighties rhythmics to bounce along to;

and the quiet, spooky, ambient themes accompanying Sonny Bonds at murder

scenes, morgues, and criminal dens are... well, as good as this kind of

«incidental music» ever gets. The «happier» themes, accompanying Marie’s

convalescence and the happy ending (‘we’re

going to have a baby!’), are full of corny chord sequences, of course,

but I guess we all saw it coming anyway. (Did you expect the game to end on a

Rosemary’s Baby note or

something?). In short, if only the music were an adequate fit for the game’s

storyline and visuals, it could have been quite a solid cherry on top; as it

is, there is a notable discrepancy between the quality of the music and

everything else. I’m not saying, of course, that Miami Vice-style music was Jan Hammer’s greatest achievement in

the world of music — that’d be like saying that Alec Guinness’ greatest role

in cinema was that of Obi-Wan Kenobi — and I’m definitely not saying that the scripts of Miami Vice were always superior to the third-rate writing of Police Quest III, but there’s still a

big distinction between pulp that makes sense and pulp that does not, and

when your composer works his ass off to provide impressive atmosphere for

your game while your writers do their worst to reduce that atmosphere to

nonsense... well, something is not quite right with this particular alignment

of the stars. |

||||

|

The gameplay of Police Quest

III generally follows the pattern of most of Sierra’s «first generation

point-and-click» games: a rather minimalistic set of options, essentially

reduced to a four-element set of «Walk», «Talk», «Look», and «Operate» (= ‘take’

or ‘use’) buttons, out of which only «Look» is universal — as I already

stated, the game’s set of responses to your actions is fairly laconic, and approximately

90% of the actions you try out will net you a red «you-can’t-do-that» cross. Even

worse, the coders did not do a very good job with the hotspots — the desk

space in the offices, for instance, is so cluttered that even if you can visually sort out the difference

between your input basket, your phone, and your computer, getting to properly

«Operate» each one of them is a challenge for the likes of Wilhelm Tell. Or,

for instance, try and open the trunk of your car in one go if the game

positions it at the edge of the screen, so that a millimeter-wide error will

have you opening the door of the car and getting inside rather than accessing

your goddamn tool kit in the back. Still, these are minor quibbles; overall, the worst thing that

can be said about the general interface and gameplay system is that it is

nothing more and nothing less than «adequate» and «perfunctory». Where it really makes sense to rant, rave, and

throw in the towel is the driving system. You might remember that in Police Quest II, player-controlled driving

around Lytton City was completely eliminated — the game would just

automatically take you where you wanted to go upon being given a destination,

which took good care of all the annoying driving problems in the first game

but also deprived you of the general «feel» of the City of Lytton around you,

reducing it to a number of small, disconnected locations. Well, now the driving is back with a vengeance — and somehow, it

manages to bring back both the

annoying driving problems of Police Quest

I and the lack of the «city

feel» of Police Quest II! This

time, the Jim Walls team came up with a sort of lite-version driving

simulator, where you are given an over-the-shoulder 3rd person view of your

car’s interior, a little window with a top-to-bottom perspective, and a

challenge to drive your car from Point A to Point B through Lytton City’s old

mesh of streets and alleys without crashing or running stop signs. The single

worst thing about this «challenge» is that it either requires you to memorize

the entire (admittedly, not too complicated) geography of Lytton in advance,

or to always have the Lytton map from your game manual lying open before you,

almost as a sort of additional copy protection. If you are ready for either

of these options, the challenge becomes not so much of a challenge but rather

a tedious bore, concentrating all of your attention on a tiny road map square

in the top right corner of your screen as you count out the street numbers so

as not to miss your turn — do it and you’ll have to make a full circle around

the nearest block, of course. To add a little «excitement» to the situation and give you the

illusion of training your driving reflexes, the team gives you the option of

speeding up and slowing down — the former is advisable for long stretches of

open road, the latter is absolutely necessary before taking turns, to avoid

crashing. Gee, this is so much fun! At least, for some innovative reason, the

City of Lytton has apparently decreed to remove all street lights (might just

as well, since the city is oddly devoid of pedestrians anyway), so your only

other problem are the stop signs installed all around the city’s perimeter (but

not between any of the interior blocks). I cannot even begin to describe how

much I hate this stupid system — beating it never really gives me any of that

classic «gamer pride», just relief that one more tedious ride is finally

over. And since I do not see any of Lytton City anyway, just a monotonous

stretch of road, the system adds absolutely nothing in terms of atmosphere. How

did they even manage to make a driving system in 1991 that makes the driving

system of 1987 feel so marvelous in comparison? Occasionally, the game takes pity on you and decides to drive

you to your next destination automatically (e.g. the hospital where you have

to visit Marie every day, or the mall where Morales regularly takes you for

her phone calls). But you can never really predict when that agency shall be

taken out of your hands; and at the very end of the game, just when you’re

finally ready to kick the bad guys’ asses once and for all, you are forced to

take not one, but three trips to

the bad guys’ hideout and back, in order to first get a search warrant from

the judge and then a special judicial order for a battering ram unit. All of

this really brings back to mind the worst simulator excesses of Codename: Iceman, and makes me

suspect that perhaps Jim Walls just hated his former job so much that he wanted the players to take pity on him for having

had to go through so much bureaucratic and procedural tedium over the years —

except that the reaction I most commonly experience while replaying through

these sequences is anything but

pity. Some strange programming decisions, too, were made for the

action sequences in the game, which are actually very few — most notably the

shootout and chase at the old saloon and the final showdown with Michael Bains

— and require little other than drawing your gun and correctly aiming it at

your target. Actually, the saloon shootout originally got me bogged down for

a bit because there is no special option for drawing your gun, as there used

to be in the parser-endowed first two games; apparently, all you have to do

is simply select it from the inventory, which somehow makes you immune to Steve

Rocklin’s bullet — yes, another rather unfortunate consequence of eliminating

the text parser and not quite understanding how to compensate with the

point-and-click interface in special circumstances. On the whole, the game feels «okay» when it is simply making you

do the run-of-the-mill adventure game stuff — and it feels either terrible

or, at least, clumsy and awkward when it tries to make you do something out

of the ordinary. Arguably the lone exception is the «Composite Master»

software, where you can actually have fun putting together your own preferred

portrait of the villain (and hear the homeless witness’ occasional ironic

quips on your progress). That little bit is quite well designed; but you only

go through it once, and you have to

drive that damn car all day long, day in and out! |

||||

|

I suppose the best thing that can be said about Police Quest III is... well, this is not a game that would give

the impression its creators were running on autopilot while designing and

programming it. Clearly, there was

a burning desire — either on the part of Jim Walls personally or Sierra in

general — to push forward those ever-pushable boundaries, to make a generally

more cinematic and involving experience, maybe even to convince the world

that there is something better than watching Miami Vice and that something is being a character inside the likes of Miami Vice. And some of those efforts

paid off — in the form of Jan Hammer’s music, or the niftily handled rotoscoped

animations, or the appearance of tension-building cutscenes, or the decision

to at least occasionally put the title character in situations that require

using one’s head in addition to one’s manual of police procedure. Unfortunately, it just

looks as if the enthusiasm for the game ran out midway through the

production, while the intelligence required to make it seem respectable was

hardly ever there in the first place. The first two games could somehow get

away with their clichéd (or, in the case of the first game, almost

non-existent) plots because they were both very much fixed on the player’s

crime-solving skills rather than the social implications of the crimes; Police Quest III, however, made the

mistake of trying to seriously play with your emotions, and in this

enterprise it failed worse than the average cheap soap opera. Throw in the

relative lack of fresh ideas, where some chunks of the game played out like

re-writes of sequences from older ones; the sparseness and boredom of the

dialog; the clunkiness of the abysmal driving system; the bugs and dead ends;

the obviously rushed and unconvincing finale — and you can easily understand

why, even within a series that usually gets fairly little respect as such, Police Quest III is so frequently

regarded as a relative clunker. I am definitely ready

to appreciate it for some of its innovative technical decisions, and I had a

bit of fun replaying it recently (other than the driving sequences, which

always irritate the heck out of me); but I do have to admit that Officer Sonny

Bonds works much better as an «anti-interesting» character in Sierra’s CGA

and EGA ages, and that he simply could not survive the transition to the VGA

age — so maybe it’s a good thing that, unlike King Graham of Daventry, Roger Wilco,

or Leisure Suit Larry, we never got to hear him talk the talk. Instead, that dubious

honor went to his successor, John Carey of Police Quest IV, a game that usually garners much more hate than Police Quest III and usually for

reasons that have absolutely nothing to do with video games — but that’s

already a whole different story which we shall tackle another time. |

||||