|

|

||||

|

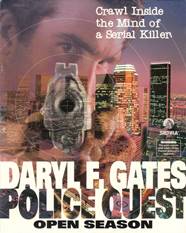

Studio: |

Sierra

On-Line |

|||

|

Designer(s): |

Daryl

F. Gates / Tammy Dargan |

|||

|

Part of series: |

Police

Quest |

|||

|

Release: |

November 1993 |

|||

|

Main credits: |

Lead programmer: Doug Oldfield Cinematography: Rod Fung Music: Neal Grandstaff |

|||

|

Useful links: |

Playthrough:

Complete

Playlist Parts 1-9 (577 mins.) |

|||

|

Basic Overview

My own memories of my initial acquaintance with the

game are somewhat blurry; I must have played a pirated copy and I do not even

remember if it was the CD version from 1996, with a full voice recording

soundtrack, or the original floppy disk version from 1993. What I do remember is an initial feeling of

disappointment. While Police Quest

had never been my personal favorite of Sierra’s franchises — has it ever been

for anybody, except possibly a bunch of retired officers? — I did get heavily

invested in the first three games, and, like everybody else, was expecting a

return into the world of Sonny Bonds and his native City of Lytton, as

designed by Jim Walls and his team. Instead, the game told me it was designed by some

guy named Daryl F. Gates — what

could a young Russian student in pre-Internet days know about this name? —

and went on right ahead to stun me with news that (a) all the action would

take place in some grimy slums in downtown L.A.; (b) the protagonist would be

a faceless detective in a brown suit called John Carey, rather than my good

vanilla friend Sonny Bonds; (c) everything would be presented in a depressing

palette of mostly brown and grey (with an occasional mix of police blue),

because where a fictional city like Lytton might be comprised of blue skies,

green parks, and brightly colored buildings, real-life L.A. consists of just

three elements — ashes, shit, and police. Under different circumstances, I

might have put the game down in about five minutes of playing time. However,

most of my context came from the previous three Police Quest games rather than any real-life L.A. experience, so

I just sighed and ploughed on. And, believe it or not, eventually I quite got

into it — yes, I sincerely enjoyed the game (at least, parts of it) without

even suspecting there might be certain «immoral» aspects to that enjoyment. Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic Ken

Williams, Sierra’s president, was being grilled — as time went by and the

game faded out of public memory, less frequently, but far more intensely with

each passing year — for hiring Daryl Gates, former chief of L.A.P.D., the

father of SWAT teams and the person chiefly held responsible for the Rodney

King riots of 1992, to design and supervise the fourth installment in the Police Quest series. According to Ken

himself, he merely "wanted our

police games to transition into tactical simulations more than just being

interactive stories. Chief Gates had knowledge of police procedures and

tactics that were well beyond what any one field officer could bring to the

table." Can’t really argue with that knowledge, can we? Honestly, though, the one thing I am not here to do is to discuss the

sensitive issue of whether it is fully or only partially justified that the

name of Daryl F. Gates, in certain circles at least, has become synonymous

with the concept of police brutality. Perhaps it is, and perhaps, as it often

happens, the actual story is a little more complicated and nuanced. What I’m

more interested in in this

particular context is whether the brief sojourn of Daryl Gates at Sierra did

actually result in the studio, formerly known for its fairly progressive and

humanistic stance on social issues, producing a drastically imbalanced

«right-wing» game with a strong conservative and racist stance, fully

deserving of the progressive hate in today’s moral climate — or whether its

chief goals were more aligned with Ken’s memories, with anything particularly

insensitive about it being more of an unfortunate side effect than anything

else. First and foremost, it is important to remember that

the principal goal of the Police Quest

series in its Jim Walls days had never been the art of «copaganda» —

naturally, with the games written and designed by a former police officer,

they would be on the whole sympathetic to the Department, but their main

purpose was to try and de-romanticize the image of the dashing,

excitement-seeking police officer from the average TV series: players would

spend much more time observing the tedious minutiae of police procedure,

filling out memos, checking car tires, stowing guns in lockers, and reading

out rights than actually chasing dangerous criminals. (And who could forget

that the biggest challenge of working undercover in the first Police Quest game was winning a few

hands of poker?). If anything, Police

Quest: Open Season put even more emphasis on that aspect; even if it were

a game that was desperately trying to be as gung-ho and racist as possible,

there was simply not enough time for the developers to indulge in their worst

instincts, as most of it had to be spent on designing puzzles that could only

be properly solved by strictly clinging to correct police procedure. (The

game even came with a 50-page

«Abridged (!) Manual of the Los Angeles Police Department» — which,

fortunately, you did not have to study in detail to complete it, but which

probably made for some inspired bathroom reading, e.g. "the prescribed trousers belt shall be worn

under the Police Equipment Belt. It shall be adjusted so that no part other

than the top edge is visible". God, I sure wish this game could take

points away from you for flashing your "prescribed trousers belt" in public!). Second, if you really need to alleviate your

conscience, it helps to keep in mind that Chief Gates never really wrote the

game. Proper credit here goes to Tammy Dargan, who had been working as a

producer on various Sierra games since 1991 and, before that, had a bit of

experience with America’s Most Wanted,

meaning that she was probably the only member of the staff «qualified» to

write a police game under Gates’ supervision. Honestly, the exact amount of

Gates’ contribution to Open Season

remains a bit of a mystery (although he does appear in person as an Easter

Egg cameo, provided you do a good job constantly returning to the useless

extra floors of Parker Center). Dargan, on the other hand, was known for a

pretty liberal pedigree, a rather telling indication on how the lines of

demarcation and separation tended to be far more blurrier even back in the

1990s (let alone earlier times) than they are today. (I read a December 1993

interview with both herself and Gates at the same time and they kinda seemed

having a pretty good time together). Anyway, it’s probably safe to say that the principal concern of Police Quest: Open Season was taking

the well-established paradigm of Police

Quest into the new technological realities of the mid-1990s — which, with

all the advances in video and sound capture, storage space, processing power,

and accompanying increases in budget, now allowed for a far more realistic

(and dramatic) approach to game-making. Any potential offensiveness of its

script, dialog, or character depiction is to be taken as an unfortunate side

effect of its day and age that, at least as far as I am concerned, can be

overlooked provided the game itself

is sufficiently fun and involving on other fronts — although this, too, is

quite debatable. Neither should Police

Quest: Open Season be confused with the Police Quest: SWAT series that, under Sierra’s name, would

continue to be released until around the mid-2000s and the first batch of

which continued to be designed by Dargan (but not Gates, even if the first game

in the series still kissed some ass by bearing the full name of Daryl F. Gates’ Police Quest: SWAT).

All of those titles are really police action simulators, not adventure games,

and although there is nothing particularly cop-a-gandish about them either,

they represent the main idea of Police

Quest taken out of its adventure game eggshell completely, working the

same way as if you’d turn Space Quest

into a rocket flight simulator or Leisure

Suit Larry into pure strip poker. I never had any genuine interest in

that stuff, and shall, of course, subject Open

Season to the same general criteria I employ for any other adventure game,

as should you. But it is

somewhat telling, perhaps, that Sierra preferred to turn their police-theme

based adventure game series into a pure simulator even years before they went

out of the adventure game business — above all, it means that Dargan herself

probably did not care all that much about the story, and/or felt that the

customers, too, would be more interested in learning to shoot their guns and

properly cuff their suspects rather than solving inventory-based puzzles or

listening to third-rate police drama dialog. Even with a new setting, a new

character, and an overall positive (at the time) reception of the game, it was

clear that Police Quest had run its

course sooner than any other Sierra franchise, and it was precisely because Police Quest was not a series about doing interesting and

extraordinary detective work — it was first and foremost a series about not

forgetting to store your gun in a locker before stepping on the premises of

the city jail, and just how many games do you need in order to impair the

importance of those kinds of rules to the player? One is probably enough; Police Quest lasted through four, and

even if the fourth one did attempt a drastic change of tone, we all know,

deep down inside, that there is not that much difference between Officer

Sonny Bonds and Detective John Carey. One thing is for certain: the Police Quest series died a natural death, not because of its

ill-fated final association with Chief Gates. In his memoirs, Ken Williams

has almost turned his entire small chapter on the final days of Police Quest into a full-fledged

apology for Gates, which does not at all come across as convincing — at the

same time, he writes almost nothing about the game itself (not surprising,

since Ken always comes across as businessman first, gamer last). We shall try

to rectify this mistake here by concentrating exclusively on the game, rather

than the unsavory aspects of its «godfather». |

||||

|

Content evaluation |

||||

|

Plotline

Police Quest: Open Season largely dispenses with

that formula. Each of its three predecessors started out in the same way: on

a bright, sunny morning Officer Sonny Bonds parks his vehicle in the cozy

parking lot of Lytton City Department and goes to work, mingling with his cop

buddies, sharing the local news and gossip, adjusting his uniform, and

wasting as much time as possible on the little pleasures of cop life before

actually going out to hunt serious crime. Yes, there are quite a few bad eggs

spoiling the quiet and happy world of Lytton City, but overall it’s a

colorful paradise where your main concern is not to forget to walk around

your police vehicle every time you take it out for a ride, or you’ll end up

with a flat tire and then you’ll just have

to miss that nice coffee break with your friend Steve over at Carol’s Cafe —

game over, man! In stark contrast, Police

Quest: Open Season opens its season in the middle of the night, with your

character parking his car in some dirty, dangerous suburb of downtown L.A. to

investigate a murder scene — a double

murder scene, as you quickly discover, with one of the victims being no less

than another police officer and the other a young boy from the local

(all-black) neighborhood. No previous game in the series threw you right

inside the action from the very start, so, clearly, plot matters much more here than it used to. If

only it were a good plot...

unfortunately, Tammy Dargan is no Jane Jensen (or even Lorelei Shannon, to

think of all those Sierra gal writers with their dark and disturbed

fantasies) when it comes to placing your imagination at the service of the gaming

community — and besides, there’s that little matter of having to conform to

the demands of «police realism» when designing a Police Quest game, so no werewolves, lost Wagner operas, or

strange aliens from Dimension X to help out the unfortunate script writer. Pretty soon it becomes evident that the plot is bifurcating into

two separate detective stories: one that is more grounded in social issues,

being directly related to the problem of gang warfare in suburban L.A., and

one with a thriller / horror twist, dealing with a serial killer on the

loose. The first subplot, centered around the killing of the little boy Bobby

Washington, is taken care of rather quickly and without a whole lot of direct

(more like collateral) involvement on the part of your character; arguably,

though, it is important in setting up the «general context» of the second

subplot, indirectly hinting, perhaps, that the overall atmosphere of violence

and fear, so predominant in those suburbs, is the perfect breeding ground for

psychopathic monsters in human form. This may, in fact, be the chief ideological contribution of

Daryl F. Gates to the game: in the eyes of its new protagonist, Detective

John Carey, the «City of Angels» is nowhere near a happy paradise with a few

bad eggs scattered around, as the fictional Lytton City was for his

predecessor on the job, but is instead a place "full of dirtbags, creeps, and losers", as he bitterly

announces a bare two minutes into the game upon learning that his cop friend

has just been brutally murdered. One might ascribe this remark to a situation

of stress, of course, but the plot of the game does little to dissipate that

impression: indeed, most of the

people you’re going to meet are either dirtbags, creeps, or losers, sometimes

all of those at the same time. Apart from a couple work colleagues, like the

cute SID officer Julie Chester, and the grieving family members of the

victims, there aren’t a whole lot of people you meet in this game that are

going to stir your sympathies. The main plot of the game hardly rises above third-rate TV

police drama, though in its final twists and turns it does try to borrow a

page or two from both Psycho and Silence Of The Lambs (again, in

progressive circles this has earned the game a reputation of being «transphobic»,

but it is hardly any more transphobic than either of the two aforementioned

movies). Along the way, we get more or less stereotypical images of the

various L.A. subcultures — from the hip-hop scene to the red lights district

to the neo-Nazi community — none of which ultimately turn out to be in any

way related to the major crimes of the game, but together constitute a

somewhat coherent, if caricaturesque, depiction of the «seedy side» of the

big city. (Given that we see almost nothing but the seedy side, I’d be more OK calling the game «L.A.-phobic»

than «transphobic» — definitely not sure that its release earned «The Big

Orange» a lot of reputation points). It feels as if either Dargan was much

more interested in having you run through this gallery of stereotypes than in

writing a proper police investigation story. At first, you do get around,

gathering clues on and from various suspects, occasionally running into a red

herring or two (like the neo-Nazi guy); eventually, though, you end up

looking more like an impartial observer of the ongoing horrors, until, at the

end of the game, a lucky turn of events (in the guise of an involuntary

canine assistant) suddenly leads you right to your destination. The ending is

openly bad: ridiculously illogical and blatantly rushed, it pretty much

negates all the effort Detective Carey puts into his investigation — you

might as well simply have done nothing at all and just patiently waited until

your last victim came along — and makes me suspect that the game was running

over budget (the most standard explanation for all the rushed endings in

video games, of which there are plenty). That said, putting aside the corny ending and the stereotypical

characters (on this issue I’ll add some more thoughts below, in the Atmosphere section), the overall

storyline of Police Quest: Open Season

is hardly among the worst I’ve seen in the world of video gaming. You may

very well be disappointed in the ending, but you will probably be intrigued enough, once you’ve started, to see the

whole thing to its end. Along the way, there’ll be at least one shootout, at

least a couple of tense moments where you have to act quickly and decisively

under pressure, and, of course, lots of talking with a variety of characters

— don’t expect any unusually sharp dialog or cleverness, because most of them

generally say what they’re expected to say in ways in which they’re expected

to say it, but then the game is all about ordinary police procedure applied

to ordinary people, and ordinary people don’t really talk the way they do in

Coen brothers’ movies. The main problem with the story is that some people

have the talent to put genius inside the ordinary, and some don’t; Tammy

Dargan, not even with Chief Gates looking over her shoulder, certainly

belonged to the latter category. The actions of her characters do not bear

much individuality, and their dialog typically walks the line between

triteness and corniness, with an occasional quasi-philosophical joke now and

then ("Dude, nothing sticks in my

mind... I’m a product of the Seventies", a corner store owner

confesses to our detective when asked one of the possible questions). It’s

not too bad, and it’s not too good, just okay, really. Mind you, however, that there is NOTHING whatsoever in this game to deserve the death warrant on

the part of The Digital Antiquarian: "this game takes its demonization of all that isn’t white, straight,

and suburban to what would be a comical extreme if it wasn’t so hateful".

This super-strong statement is then backed by exactly two examples: (a) the serial killer is a transvestite (oh gee,

let’s toss Silence Of The Lambs

into the trash bin as well while we’re at it); (b) one of the in-game police

files describes a street gang that consists of "unwed mothers on public assistance" — something that could

certainly be construed as offensive if it was not totally taken out of its

general humorous context; the tradition of thinking up hilariously

exaggerated descriptions for criminals and gangs goes all the way back to the

first Police Quest. Anyway, if one

needs to dig that deep inside the

bowels of the game to find something «hateful» about it — reading those files

is completely optional, for the most part — then it is clear enough that some

people just need to read so much more into this thing than it actually

contains. For sure, if you happen to share some extreme

«defund-the-police-to-solve-all-our-problems» mentality, you’ll find every

bit of the game offensive — but you’ll probably do the same with each of the

previous games in the series as well, and even more probably, you won’t even

be interested in trying any one of them out or reading this review in the first place. |

||||

|

Puzzles

The main problem with this (generally logical and meaningful)

design is that, ultimately, it does not matter. Forget to do all these

things, be a sloppy and irresponsible cop all the way through, and all you

end up with at the end of the game is a low overall score that you aren’t

even properly reminded of unless you bother to check the separate and

unintrusive stats screen every once in a while. True, missing a couple of really important things — like having

to go through the same annoying shooting exercises each day of the game —

will eventually result in a permanent game over, but for the most part, you

have nothing but your conscience to worry about. It would have at least been

nice to have some sort of «Sleuth-o-Meter» displayed at the end of the game,

or have some official judgement passed on you by your commanding officer, but

ultimately the game leads either straight to your death if you do something

really stupid or careless, or to your commendation for solving the case

(which, honestly, should have instead gone to the dog, who does most of your

work for you). It certainly does not help that, with all the miriad of

micro-managing mini-tasks set out before Detective Carey, some of the

challenges are hopelessly bugged; for instance, some actions performed at the

«wrong» time (that is, before or after some other actions) can leave you without

the coveted points, even though there is absolutely no logical explanation

for why that is other than an elementary programmer’s mistake, not corrected

in any of the game’s ensuing patches. This is also a part of Police Quest’s legacy — for a game

that prides itself on teaching the player the meaning of discipline, it sure

is ridiculously buggy — and it’s a psychologically nasty blow for

completionists, who can waste hours trying to do everything right only to

discover, at the end of the game, that life is out there to punish you for

your effort, not for your laziness. This is particularly surprising when you realize how much work

went into, for instance, the writing of the game’s dialog when it comes to

interaction with the game’s NPCs. Typically, Sierra games have a very limited

number of reactions when you try to use various random objects from your

inventory on people or things around you; in Open Season, however, you can expect something to happen when flashing your badge — or, for that

matter, even an empty glass jar from your toolkit — not only at your

colleagues, superiors, or witnesses, but even at random patrons in the local

bar. The writers really saw to it that the city came alive, or that you would

not get too bored in the typical

adventure game situation of being stuck on a puzzle and resorting to the «try

everything on everyone» technique to break through. I honestly wouldn’t mind

if a bit of that verve were spent on filtering out bugs instead, but I do

admire the effort. Outside of the usual inventory-based puzzles and dialog trees,

the game does not offer a lot of extra challenges. The driving system,

earlier removed in Police Quest II

and reinstated in Police Quest III,

is once again removed, perhaps because of negative feedback for the third

game. The shooting range, which you have to beat in order to stay alive, is a

trivial task for anybody with relatively decent eyesight, which makes it

particularly annoying when you have to complete it at least three times (they

could have at least varied the challenge, but it’s always the same). There is

one shootout sequence where you have to be just a little bit nimble, and a

few cases where you have to make split-second decisions to avoid near-instant

death, but that’s about it, I think. In this way, Open Season does not break with tradition — Police Quest had always taken pride in being strictly in the

adventure game camp and nowhere else, which makes it all the more surprising

how quick Tammy Dargan would be to break with that tradition when she would

turn the franchise into the S.W.A.T.

simulator the very next year. In terms of «player comfort», Open Season shares Sierra’s general ideology of the mid-1990s,

copied over from LucasArts: relatively few death opportunities (cropping up

in about 4-5 situations which are clearly rife with danger, so you’ll

probably be prepared) and no chances of softlocking yourself out of the game

by doing something you’re not supposed to do, like dropping a key item —

well, except when you fall victim to one of the game’s many bugs, some of

which still remain unpatched. (Like I already said, it’s pretty easy to

softlock yourself out of the highest score, though). You do have a small chance to get stuck near the end of the game,

because both Jim Walls’ and Tammy

Dargan’s Police Quest are typically

at their weakest the moment it comes down to the protagonist having to think

a little outside the box and improvise, instead of rigidly clinging to

prescribed police procedure. As long as 99% of your time is occupied by

investigating crime scenes, talking to witnesses / suspects / work colleagues

etc., filing reports, and practicing your shooting, it’s OK. But the final

set of puzzles, in stark contrast to the general spirit of the game, is

purely nonsensical. The most glaring example (spoiler alert!) is when, for some unexplainable reason, you have

to lasso a suspicious dog in the random hope that it might lead you to the

killer — is that a standard prescribed tactic for an LAPD officer? — and in

order to lasso the dog, you have to procure yourself a barely visible piece

of rope from an inconspicuous paper bag in a garbage dump that you most

likely have already inspected several times in the first part of the game.

Because, you know, it’s a normal thing — in L.A., if you need a piece of rope

for some reason, your obvious destination is the nearest garbage dump.

Because, you know, who’d want to spend a chunk of one’s meager police officer

salary on a piece of rope from a local hardware store? Still, I do not want to create the impression that the entire game rides that kind of

ridiculousness; clearly, the final stretch was done in a hurry when the team

discovered it was running over budget or something. For the most part,

puzzle-wise, it’s okay: not great, not terrible, like most Sierra games from

that period. And given how many different types of reactions you can get by

trying out «wrong» solutions to your issues, it seems rather clear that the

main emphasis was on the ambience, rather than on all the brainstorming — so

let’s get to the ambience already. |

||||

|

Atmosphere

While

there certainly is a modicum of truth in such an impression, let us also not

forget that this is a (slightly

soapy) police drama, meaning that it has

to concentrate on "dirtbags, creeps, and losers" by its very

definition; condemning Open Season

for sticking to the «police good, scumbags bad» principle would be like

complaining that The Wire never

once gave us a guided tour of The Baltimore Museum of Art. The game does try

quite hard to depict those areas of L.A. that you pass through as a

life-during-wartime zone: the overriding colors are gray and brown, garbage

and gang-related graffiti are everywhere, and absolutely nobody is happy in

any way, other than an occasional crazy or two — attitudes generally range

from openly hostile and aggressive to wary and vigilant. But there are quite

a few characters written and acted out in order to evoke sympathy from the

player: the widow of the downed police officer, the desperate mother of the

black boy who became a collateral victim, even the working ladies in the red

district are all presented as... well, as people worthy to be protected by

Detective Carey, let’s put it that way. Stereotypical, sure, but worthy. Unfortunately,

because you do not get to drive around the city, you only get to experience

isolated «pockets» of it; still, I would say that it manages to paint a more

expressive portrait of an urban environment than the previous two Police Quests, with much more

attention dedicated to specific details. NPCs that are not directly related

to your quest are relatively scarce, but they do exist and can be interacted

with in different ways. The locations themselves are fairly varied — you get

to see suburban residences in both white and black areas of the city, a posh

rapper mansion, a creepy neo-Nazi den, a «working girl» establishment, an

indie movie theater, a barroom where cops like to hang out after work...

well, nothing that rises above the usual tropes, but certainly more diverse

and representative than it used to be in Police

Quest III. One

specific criticism of the game was in its representation of African-American

characters and especially their speech patois ("yo, I be fly today" is the most often quoted example).

According to Dargan, her primary inspiration for writing characters such as

«Raymond Jones The Third» and «Yo Money» was Fab Five Freddy’s Fresh

Fly Favor: Words And Phrases Of The Hip Hop Generation, one of those

humorous «first-source» slang dictionaries whose typical problems are that

(a) it only represents one particular slice of dialect from one particular

location, (b) inevitably gets embellished by its own creator in the most

subjective ways possible, and (c) gets terribly dated a year or two after

publication. On the other hand, I believe that this problem, too, is much

exaggerated — the actual African-American actors who voiced those roles seem

to have had little problem with the jargon, and for about 90% of the time, it

does not deviate too terribly from speech patterns that persist up to this

day (and, in fact, are steadily adopted more and more by

progressively-oriented white folks). If, every once in a while, a "this be my hood" or two creeps

in, well, hell, I’ve seen Instagram photos subtitled "this be my hood" without any

tongue-in-cheek attitude, so let’s not get too riled up about things that

just aren’t worth it. (I have only recently read an interminable discussion

on Reddit about the allegedly embarrassing use of the word hella by a teenage character in Life Is Strange, and couldn’t stop

wondering about how much more productive the discussion would have been if it

tried to keep strictly focused on the sociolinguistic aspects, instead of

constantly derailing into silly emotional outbursts of «who the hell talks like that?» and «what business do those French game designers have trying to mimic

American teen lingo?», even though the actual dialog was written by an

American writer). Stereotypical

or not, I might add that the writers did a pretty good job supplying most of

the characters in the game with some

sort of personality. For Jim Walls, making his city of Lytton come alive

always seemed like an afterthought — even when the game featured bystanding

NPCs, they were, at most, procured with a generic replica or two ("Good day, Officer! Nice weather, isn’t it?");

only in Police Quest III some of

the characters began developing a little character, by which time it was

already too late (and, by the way, I think it was probably Jane Jensen,

rather than Walls, who was responsible for advancing those NPCs from pure

mannequin stage to something slightly advanced). In Police Quest: Open Season, on the other hand, the morgue

assistant will be cracking jokes non-stop, the morgue receptionist will be an

empty-headed girl with nothing but nail polish on her mind ("you have an appointment to shoot your gun?

I have an appointment to get my nails done!"), the tow yard guard

will be a personage out of an imaginary Coen Brothers movie, the neo-Nazi

thug will use the F-word more frequently than any hero in any Tarantino

flick, and the psychotherapist at the health care center will say stuff like

"please don’t touch my plant, she

doesn’t like to be handled, she had a bad experience once, she still hasn’t

gotten over it". Much, if not most, of this will be predictable,

some of it will be cringeworthy, a bit of it will be smart, but on the whole,

meeting new people in the game is always accompanied with a touch of

intrigue. And

a touch of tension, too. In an odd way, I cannot help thinking about the

overall atmosphere of Police Quest:

Open Season without placing it in the context of the other Sierra game

that was being polished at the same time and with which it shares quite a few

features in terms of graphic and gameplay design — Jane Jensen’s Gabriel Knight: Sins Of The Fathers.

Although the latter is, without any questions, FAR superior to the

Gates-Dargan project, both games focus on adding a permanent sinister layer

on things you’d normally think of as relatively familiar, cuddly, and safe

(New Orleans is no longer the «Big Easy» capital of jazz and Mardi Gras, but

the central residence of the spirit of Black Voodoo; Los Angeles is no longer

an embodiment of the spirit of Hollywood, but a constant reminder of the

aftermath of the Rodney King riots). This was, on the whole, a period when

Sierra On-Line was «going dark», subtly shifting its focus from light comedy to

more mature themes, and Daryl Gates’ vision of contemporary L.A. as a war

zone, regardless of its degree of realism or bigotry, strangely enough, fits

pretty well into this evolving paradigm. I cannot for a moment admit to

really digging this atmosphere, but I get it, and I certainly recognize its

right to existence. Let us now take a brief look at the technical means used

to create it. |

||||

|

Technical features |

||||

|

Unquestionably the most innovative and — for its time — technically

impressive aspect of Open Season

was its visual artistry. This was Sierra’s first (and, ironically, last)

adventure game that almost completely forsook both hand-painted and pure

digital art in favor of actual photoshots of real exteriors and interiors of

L.A. that would consequently be scanned and edited into digital backdrops;

likewise, all the static and dynamic action for playable and non-playable

characters was produced through motion capture technology used on real

actors. Essentially, this was just one step shy of full-motion video, which

Sierra would endorse two years later, but not quite there yet; however,

compared to the studio’s other games from the same year — such as Gabriel Knight or Leisure Suit Larry 6 — this was a huge step up, not very

revolutionary, perhaps, in terms of the overall video game perspectives (the

animated sprites in something like the original Mortal Kombat put their equivalents in Police Quest to shame), but very much so in terms of a realistic,

immersive approach to adventure games. Alas, like so many other things, these particular technologies

have not aged particularly well; not quite as awfully, that is, as most

instances of early 3D modeling, but still, the hand-painted and animated art

from the above-mentioned games looks much

better on modern day monitors than all the «photo-realistic» stuff in Open Season. For one thing, «realism»

means perfunctory pragmaticism — in 1993, the only reason to admire most of

those shots was how unusually realistic they looked on your screen, but now

that standards for «realism» have jumped sky high compared to those days, we

can only enjoy the vistas of Open

Season if they convey a certain aesthetics, and conveying aesthetics was

probably the last thing on the minds of the game’s developers. What you get

is simply a generic, uninteresting, and poorly pixelated approximation of

various places in Los Angeles. Like Parker Center — you

could argue that the game at least preserves a snapshot of the exterior of

this historical landmark before it was demolished in 2019, but the problem is

that the building always looked terrible (not that you’d expect police

stations to look aesthetically pleasing anywhere other than the Resident Evil universe), and gazing at

a 640x480 representation of a corner of it on a big screen is hardly going to

do much for its looks. Another

thing is the color palette: while the overriding brown and ash-grey colors of

the game clearly have a symbolic importance, it’s ultimately more than a

little depressing to spend the entire game in this setting, as opposed to the

generally bright and uplifting colors of Lytton. The only times this

impression changes are the predictable environments of the morgue (mostly

white, of course) and the Itty-Bitty Club (where everything is drenched in

more red than David Lynch’s Black Lodge). Taken together with the low

resolution, this combination makes certain environments look like a chaotic

mess of drab, vomit-colored pixels (like the interior of Kim’s five-and-dime

store, for instance). In the end, the pictures of the game fail to make it

look memorable, pretty, or sinister; anything it brings to the table in terms

of atmosphere is rather conveyed by means of sound than visuals. The

animated sprites, brought to life with motion capture technology used on real

actors, are also fairly average, even for the standards of 1993. It’s not

nearly as embarrassing as those moments in Sierra’s early FMV games, like Phantasmagoria, where everybody was so

proud of the new technology that you had to waste away lots of precious

seconds watching actors slowly fling back their hair, leisurely stretching in

the middle of the room, or closing an average door with as much cautious

diligence as they could muster, just because, you know, they could. Here, too, you sometimes have

to endure an NPC take a moment or two of vanity before engaging in dialog

with your character, but it is never quite that obvious; even so, it is hard to imagine somebody in this

modern day and age being impressed by those bits of gratuitous gesticulation. Surprisingly,

there are next to no cutscenes and almost no close-ups of characters

throughout the game — and in those few instances when you do get a relatively large realistic

face up on screen, there is nothing particularly attractive or impressive

about it, unlike the highly evocative visual art of the close-ups in, say, Gabriel Knight; again, it’s all simply

about «hey, that’s a real person’s face articulating in the middle of your

monitor, how cool is that?» — well,

it wasn’t even such big news back in 1993, let alone a quarter century later.

In short, this is just another story of how visual realism never really works

if it is turned into a stand-alone value for its own sake. Moving on. |

||||

|

Sound The original game, released in November 1993, only came out on

floppy disks, with no space for a full audio soundtrack; all the text had to

be read, and the sound was limited to various audio effects and a basic

musical soundtrack thrown together by Neal Grandstaff, one of Sierra’s

composers in residence and a major presence on most of the company’s games

from 1993 to 1995 (you can easily tell when, for instance, the elevator muzak

theme from Leisure Suit Larry 6

unexpectedly crops up inside the elevator in Parker Center, most likely

producing a leery chuckle from any regular Sierra customer at the time). The

score was no better and no worse than it had always been in the Police Quest series: actually, Neal

had a seemingly tough job to follow Jan Hammer’s professional work in Police Quest 3, but I think he did

alright, focusing a little less on making the whole thing sound like a

stereotypically police soap opera and a little more on supporting the

atmosphere of darkness, tragedy, and suspense. The corniest moments are the

ones that take place in public or «culturally marked» locations — such as the

funky theme played in the mansion of «Yo Money», or the strip club muzak, or the

goofy variation on the Horst Wessel Lied playing on the stereo in the

apartment of the neo-Nazi guy — but even those are good enough for a laugh. As for the voice acting, the whole wide world had to wait for

two more years, baited breath and all, for the CD-ROM edition of the game

with full voice coverage. In the end, all of the voice actors were different

from the original actors used for motion capture, and none of the names were

recognizable — apparently, the budget was so small that the studio could only

allow itself a bunch of relative unknowns (at least they managed to avoid

filling in the gaps with Sierra’s own employees, as they had to do in the

earliest days of voice-powered games). The result is a game full of rather

predictable, but not awful performances — I struggle to remember even a

single job that made an actual impression on me, but the only moments of

genuine cringe are associated with the actors working too hard to exaggerate

their accents or speech deficiencies. Bob Liberman’s panicky stuttering for

Russel Marks, the nervous owner of the movie theater, is probably the worst,

and Denise Tapscott also tries way too hard to portray Sherry Moore, the

morgue receptionist, as the quintessential

nothing-but-nail-polish-on-her-mind girl, though the blame should probably

lie on the voice director rather than the recording artist. Unfortunately, Doug Boyd, voicing the main character of the

game, remains throughout the very epitome of mediocrity. One could argue that

completely stripping his hero from any sort of genuine emotionality works

reasonably well in work-related situations (that’s what «professional

conduct» is all about, after all), but this eventually spills even onto

situations where the hero is supposed

to show some rage, and he still comes through like a wet blanket. Almost

every other character in the game has at least one or two emotional states —

for instance, the coroner in the morgue can relatively easily switch between

the «cynically humorous tongue-in-cheek» approach and the

«deadly-serious-and-preoccupied» manner — but Detective Carey is clearly a

rock, an island, and a virtual intelligence interface rolled into one, which

makes playing for him not particularly rewarding. Then again, maybe that’s

exactly the kind of character Chief Gates needed to reflect his vision. Returning to the issue of accents and vernaculars that was

briefly touched upon in the Atmosphere

section, if you’re real sensitive about it you might probably want to

restrict yourself to the non-talkie version of the game, so as to avoid too

much pain from the hyperbolized deliveries of African-American and Asian

characters — I don’t find them as caricaturesque as some of the game’s reviewers,

though; stereotypical, yes, but hardly out there to make the average white

gamer snicker at the goofiness of all them «colored» people. Bottomline is,

everybody is trying quite hard to impersonate precisely the stereotype they

are being thrown — the bratty / arrogant lady of the famous rapper, the

chatty Southern old guy guarding the tow station, the pretentious and snobby

psychotherapist lady at the health center, the sleazy-but-caring Madame of

the house at the club, the list goes on and on and it gets a little tiresome,

but never truly out of hand because, fortunately, all the actors only have a

very limited amount of lines to go on. |

||||

|

Interface

On the other hand, the available options beyond the usual

inventory-operating and dialog mechanisms are almost non-existent in the

game. Several times Detective Carey has to go to the shooting range, with a

very trivial and unrewarding shooting mini-game involved (remaining exactly

the same all three times you have to complete it to maximize your score), and

one time there is a shootout where (provided you do pick up the shotgun) it’s

also a rather trivial matter of timely reaction and absolutely nothing else.

Speaking of shootouts, death situations are rare in the game, but they do

exist and sometimes crop up in the least expected situations (such as repeatedly

«harrassing» the photographer at the station — see, the game actually gives a

shit about woman rights!), although the accompanying animations are

surprisingly timid (usually the screen just dissolves to red-and-gray around

you — lazy as heck). The challenge of driving around, as I have already mentioned,

has disappeared; moving from one location to another is accomplished by means

of an in-game map where points of interest are gradually unlocked through the

game — again, quite similar to moving around in Gabriel Knight, though nowhere near as stylish (for instance,

different locations on the GK map

were all marked with symbolic icons, helping you to quickly and efficiently

identify them, whereas the ones in Police

Quest are all presented as boring red dots, and you have to hop from one

to another to check their pop-up tags — annoying!). Most of the locations,

once you have indicated the desire to check them out, are introduced with a

static animation, which is cute the first time around and then, of course,

becomes time-consuming — you’ll have to take in the sights of the butt-ugly

exterior of Parker Center so many times while playing, you might start

considering a career in the demolition business. On the whole, everything about the game’s interface serves the

same «pragmatic» goals as the game’s script and mechanics: even the font of

the subtitles is arguably the least aesthetic font ever to be found in a

Sierra game — a small, ugly, typewriter-style monstrosity to emphasize the

procedural routine-ness of Detective Carey’s work. Since this was an

intentional part of the design, it’s hard to blame the game for that, and it does do a pretty good job at making

you feel bored, drab, and miserable with all these visual and stylistic

settings — the only question is, do

you want to feel this kind of miserable? |

||||

|

«Good» or «bad», Police Quest: Open Season is, at the least, a

very revealing product of its time — and, in being that, is a curious

document of the American state of mind in the early 1990s.

While it is nowhere near a true classic of the adventure game genre — next to

titles like Gabriel Knight or Day Of The Tentacle from the same

year, it can at best limp along like an inconspicuous lapdog — it has one

serious advantage over everything else in sticking to realism and true

relevance rather than escapist artistic fantasy; and, with the advent of new

technical possibilities as well as the «maturation» of the adventure game

genre as a whole, it has the chance of enhancing that realism in more

detailed and psychologically subtle fashion than any of the Jim Walls-led

games in the franchise. The only problem is,

transitioning from fantasy to realism in a video game rather dramatically

raises the stakes, because this is where the video game market enters into

straightforward competition with «serious» art, a competition in which it is

almost inevitably bound to lose. The plot, the dialog, the atmosphere of Open Season could hardly be on par

with even a mid-level police-themed soap, and the advantageous factor of

personal immersion is hardly enough to compensate for that. Ultimately, the

game fails because it is too boring, clichéd, and predictable, not

because it tries to enforce Daryl F. Gates’ vision of the black-and-white contrast

between the Corrupted Criminal and the Courageous Cop. In trying to show us

the ordinary routine of the law enforcement universe, Gates and Dargan set

the same serious challenge for themselves as Jim Walls did earlier — try to

make us find excitement and fun in the ordinary — but lack the talent to even

begin overcoming that challenge. It does not help

matters, either, that the game ultimately violates its own consistency and,

when it comes to the denouement, chucks all that police realism outside the

window, going for an absurd, cheap horror movie vibe at the end that suddenly

brings it onto the turf of contemporary ridiculously titillating experiences

like Night Trap. It is not even the

corny vibe of the ending that feels wrong, but rather its blatant incongruity

with the rest of the game — whose main message during its first 80% seems to

have been along the lines of "Look

at me! I’m tedious and generic, but at least I’m not cheesy!", but

then the final 20% are like "Okay,

now I’m cheesy and there’s nothing wrong with it!". It’s downright

the equivalent of trying to quench a raging fire with a can of gasoline. And yet, despite all

that, I still found myself entertained while replaying the game for this

review. Perhaps it is just the usual predictable bias of an adventure game

fan, but somehow I find some odd value in disasters such as these from the

early days of videogaming. I can see that, while it is difficult to throw the

tag of «labor of love», the Police Quest team really made a

serious effort to push forward some boundaries, and I appreciate the fact

that they were not simply imitating the legacy of Jim Walls, but deliberately

tried to combine its fundamental principles with a more realistic and gritty

take on the darker side of life in the big American city. There is no doubt

that, if given a chance to be handled properly, the franchise could transform

into something genuinely great — transitioning from the video game market

answer to Miami Vice into an

equivalent of The Wire. Instead,

Sierra preferred to go the technical-tactical route and turn the whole thing

into a series of straightforward simulators, squashing any further

aspirations at intelligent story-telling long before becoming squashed

itself. Ultimately, this has

resulted in a situation where the adventure game genre, having begotten so

many first-rate detective games

(e.g. the Tex Murphy or Nancy Drew series), has remained

deprived of an equally first-rate police

game — and with both the police theme and the point-and-click genre not going

through the best of times at the moment, there’s little chance of remedying

that situation in the foreseeable future. Which, in turn, is a bit of a

saving grace for Police Quest: Open

Season, a game that I do not really like a lot but still open-heartedly

recommend to those seeking to expand their gaming horizons. You probably

won’t fall in love, either, but you will

be in for something... «different». I think even the self-professed haters

would confess to getting an unforgettable impression, or else how could they

generate so much bile? |

||||