|

|

||||

|

Studio: |

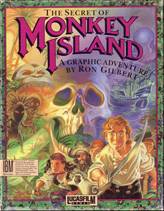

LucasArts |

|||

|

Designer(s): |

Ron

Gilbert / Dave Grossman / Tim Schafer |

|||

|

Part of series: |

Monkey

Island |

|||

|

Release: |

October 1990 (original) / July 15, 2009 (remake) |

|||

|

Main credits: |

Graphic Art: Steve Purcell, Mark Ferrari, Mike Ebert, Martin

Cameron Music: Michael Land, Patrick Mundy |

|||

|

Useful links: |

Complete

playthrough (Special Edition only;

5 parts, 260 mins.) |

|||

|

My name’s Guybrush Threepwood, and I want to be a pirate. There is a faint chance

that you might have heard this line from somewhere even if you are 18 years

old and your mom hadn’t even hit puberty when The Secret Of Monkey Island hit the market back in 1990. Because,

although the Monkey Island titles

may not be among the most inventive, the most profound, or the most

revolutionary games in the LucasArts store — such games as Day Of The Tentacle, Grim Fandango, or even Loom have them solidly beat in many

different respects — somehow ultimately it is Guybrush Threepwood who has

emerged victorious as the primary mascot of LucasArts, if not classic

adventure gaming in general. He is the ultimate lovable anti-hero, the

exemplary trickster without a cause, the embodiment of pure, unadulterated

zaniness which transcends both parody and satire and veers off into the same

uncharted territories as Monty Python. He is the reason why generations of

adventure game players still burn with nostalgia for some of those old times,

and are happy as heck whenever they succeed in passing a bit of that spark to

their younger offspring. And, being way larger than a pirate’s life, he also

bears a bit of responsibility for the demise of the genre... but all in due

course, mates. Conceived around 1988 by Ron Gilbert,

the main genius behind most of the early LucasArts classics, Monkey Island was originally intended

to be LucasArts’ stereotypical game with a pirate theme — largely to indulge

Gilbert’s childhood love for Pirates Of

The Caribbean (not the movie, which did not exist as of yet, but rather

the amusement park). But Gilbert’s weirdly warped mind simply refused to

process reality with realism, meaning that if you hoped and aspired for an

actual pirate game, you should have rather been knocking on Sid Meier’s door.

Instead, Gilbert produced an «anti-pirate» game, one that ended up

anachronistically merging perfectly modern attitudes with an allegedly

17th-century setting, and lampooning both with an equally irreverent verve. Above everything else, though, it gave

adventure gaming its very first protagonist to form a special, intimate bond

with you, the player. It is true

that playable characters in most LucasArts games specialized in breaking the

fourth wall from the very beginning, but Guybrush Threepwood did this with a

particular flair, and had more depth (and width, and height) to him than,

say, Zak McCracken or even Indiana Jones. A little nerdy, a little naïve,

moderately sharp-tongued, and clearly a romantic teenager at heart, he was

pretty much the perfect PC for the geeky young adventure gamer of the early

1990s; and unlike many other characters, he managed to carry his charisma

pretty much intact into the more modern gaming eras. Of course, it is

difficult to imagine a game like Secret

Of Monkey Island being made today (unless we’re talking about the

ivory-tower based indie adventure community), but it is not difficult to

imagine a game like that still being played and admired today, as it

admirably navigates past all the sensitive topics and still manages to be

witty and funny. |

||||

|

Content evaluation |

||||

|

Boiled down to its essence,

the story that Gilbert and Co. told us in The Secret Of Monkey Island is, well, fairly standard Pirates of the Caribbean Disney type

material. A young man dreams of becoming a pirate, goes through several

challenging trials to prove his worth, meets and falls in love with a

beautiful damsel along the way, and goes on to rescue her from the competing

hands of an evil ghost pirate, assembling a loyal crew and following the

kidnapper almost to the end of the world. What’s new? Nothing, except that

the young man’s name is Guybrush (legend states that guy.brush was the original name for the character’s sprite file),

the trials are as ridiculous as they come, the damsel makes it clear that her

rescuer is actually in bigger distress than she is, the loyal crew does not

even lift a finger to help their captain, and the evil ghost pirate is

overcome with... a bottle of root beer, more or less. In other words, the game’s plot is

thoroughly protected from being moth-eaten by clichés of the

swashbuckler genre because it thrives and feeds on those clichés,

ridiculing and inverting them at every step — which is, of course, the game’s

very reason for existence. Arguably the most fondly remembered and often

quoted example of that is the trial of sword fighting, in which Guybrush

learns that the most important part of the fight is not the physical mastery

of your weapon, but the intellectual mastery of the art of proper taunting (soon you’ll be wearing my sword like a

shish kebab!). Of course, the authors got that idea from classic Errol

Flynn movies, where it was hovering around, just waiting to be picked up, but

they did pick it up and successfully ran with it. Likewise, many a movie had

previously exploited the theme of having the protagonist Assembling A Team

only to find out that he could probably stand a better chance if he pulled

the job off on his own — but only in Secret

is that idea carried to its glorious conclusion, where you have to spend a

good third of the game putting together a mish-mash team of a bunch of

deadbeats, only to immediately realize that their only function on your ship

is that of heavy ballast. (Which is why I always end up sinking the ship

after landing on Monkey Island — it’s just so deeply satisfying). However, simply inverting

clichés is only half of the masterplan: the other half, in true Monty

Python spirit, is to fill the game up with all sorts of delightful

anachronisms, which fulfill the double function of making you laugh and

bringing the atmosphere of the game more in touch with the modern spirit (or,

more accurately, with the post-modern

spirit). This involves both specific situations (for instance, digging up

T-shirts instead of more conventional «treasure») and specific characters

(such as Stan the ship salesman, modeled after every annoying salesman in

comedy movies from all time). The (semi-)rational explanation for why

Guybrush Threepwood keeps acting like a present day teenage nerd rather than

the expected cousin of Jim Hawkins would only appear in Monkey Island 2, but the genre as such does not really require an

explanation: don’t think it over, just enjoy the overall goofiness. Being the very first game in the

series, and produced at a relatively early stage in LucasArts history, Secret does suffer from being a bit

short. Except for Guybrush himself, each character, including the love

interest Governor Elaine Marley and the arch-enemy Ghost Pirate LeChuck, gets

a very limited amount of screen time and only a small handful of dialog

lines, making them rather two-dimensional (thankfully, this flaw would be

largely rectified in the next game): LeChuck is just your stereotypical

cartoonish evil guy, Elaine is your stereotypical strong female character,

and everybody else is usually reduced to a single function (salesman Stan’s

is to annoy the hell out of you with his endless yapping, lonely pirate

Meathook’s is to demonstrate the effects of traumatic experience on the

swashbuckler’s unstable mentality, etc.). But to condemn the game for such

limitations is like condemning a 16th century novel for not showing the

psychological depths of a 19th century one — Secret Of Monkey Island should be compared to what came before it, not after it, and which computer game before it happened to have a

protagonist whose chief talent was holding his breath for ten minutes, and

who would be told that "to be a pirate, ye must be a foul-smelling,

grog-swivelling pig"? |

||||

|

Despite all the humor and whackiness

and stereotype inversions, Secret Of

Monkey Island is still first and foremost a classic adventure game, and

this means heavy emphasis on puzzles — for each heartfelt outburst of

laughter you will experience many, many minutes of figuring out where to go

next and which outrageous combination of objects should be produced to solve

the next challenge. In a well-advertised «anti-Sierra» move, Gilbert does

take pity on the players by completely wiping out the option of being able to

die and any possible deadlocks resulting

from taking a wrong turn or wasting a precious object at some earlier point

in the game, completely eliminating the need for constant saves and restores.

However, this comes at the expense of thinking up fairly harsh puzzles — and

in a game where logic is Pythonesque and imagination runs wild, this can

easily translate into hours of frustration (could, that is, in the pre-Internet-walkthrough era). That said, compared to even the second Monkey Island game, Secret is relatively forgiving in

that respect: there are fewer locations to turn to, fewer objects to roam

for, and somewhat less outrageous solutions to come up with (yes I’m looking

at you, stupid «monkey wrench» puzzle!). In fact, the game even has a

hilarious send up of such outrageous solutions — at one point in the

storyline, you end up losing control of Guybrush as he takes things into his

own little AI hands and performs a set of actions such as «give stylish

confetti to heavily-armed clown» and «push tremendous dangerous-looking yak»,

which probably parody classic text adventure games even more than late

Eighties Sierra or LucasArts, but are still hilarious all the same. As for the actual puzzles, most of them

still fall under the «find objects A and B and combine them into object C to

use on object D» category, and follow their own, slightly warped, but

ultimately understandable and often even predictable Monkey Island logic.

Sometimes you might find yourself stuck due to a timing requirement, but just

as often the game is willing to bluff you into dreading a real murderous

challenge when the answer is far more obvious (like the situation where

Guybrush has to confront Meathook’s deadly parrot). The honor of best design should

probably go to the insult sword fight challenge — it is not much of a

«puzzle» per se as soon as you figure out what to do, which is essentially

just to fight a bunch of pirates one by one until you memorize all the proper

«ripostes», but the best part is the final fight with Carla the swordmaster,

where you have to match all your collected answers to questions that are different from the original ones:

presumably a big surprise for all new players, and a nice as heck example of

the linguistic prowess of LucasArts’ dialog writers. Actually, special

mention must be made of the dialog capacities of the game — Secret was one of the very first

games to not only introduce the option of giving out different answers during

a conversation, but also sometimes, though still very occasionally, to have

different answers cause different outcomes: some of the puzzles are, in fact,

dependent on that, like haggling with Stan over the boat price. |

||||

|

As in most LucasArts games,

this is primarily what we came here for.

More than about the plot, the puzzles, or the visuals, the game is really all

about the dialog. From the very first bits in the intro — "so you want

to be a pirate, eh? You look more like a flooring inspector!" — and down

to the very last bits in the outro — "at least I learned something from

all of this... never pay more than 20 bucks for a computer game!", you

know you want to click on everything and everyone just to hear what these

absurd projections of post-modern conscience into the quasi-17th century have

to say to you. The humor is piled on so thickly that even if, at some point,

the game does seem to want to scare you (particularly in the last part, when

you are walking through mushroom-infested psychedelic-inferno corridors to

find LeChuck’s ship), it still fails ("I had a feeling that in hell

there would be mushrooms", Guybrush sighs upon entering the place,

reflecting Gilbert’s alleged mycophobia). Well, actually, forget that, there is no point at which the game can

scare you unless you are 10 years old at max and ghost pirates make you want

to jump under your pillow. That said, if seen from a slightly

different angle, the humor of Monkey

Island can be seen as almost as much of a curse as it is a blessing.

Other than the childishly innocent (and occasionally childishly mischievous)

Guybrush himself, the only «sympathetic» character in the game is his

spontaneous love interest, Governor Marley, and she only gets a grand total

of two (three, if you’re lucky and did your quests in the right order) scenes

in the entire game. Everybody else, from the strictly-business Voodoo Lady

and down to the whiny, but pragmatic shipwreck survivor Herman Toothrot, is

only here for the laughs, no third dimension necessary to any of these

characters. This is not a tragedy by any means, but it clearly shows why the

game (along with all of its sequels) ultimately feels so slight next to

something like Grim Fandango,

where the characters would be just as funny but managed to have a modicum of

soul to them as well. Needless to say, if you ever came here

in hopes of taking a digital whiff of the actual Caribbean spirit, you were

deeply mistaken — there is even less of that in this than in the Pirates Of The Caribbean franchise

which inspired the whole shenanigan, and quite intentionally so. The

characters look, act, walk, and talk as if they were all clones of Robin

Williams doing 17th century cosplay, around locations which look more like a

joyride than an actual set of islands in the Caribbean. Had the game

designers opted to put Guybrush in the Wild West instead, or the Roman

Empire, or any other mythologized quasi-historical setting, they only had to

change a few backdrops, a couple of names, and a batch of jargon — the only

function of the whole «pirate» theme here is to actually provide a theme,

much like with the Arthurian setting in Monty Python’s Holy Grail. And, of course, there is absolutely nothing wrong

with that as long as the witty jokes keep coming. |

||||

|

Technical features Note: The following section will cover (and, where

necessary, compare) both the original 1990 edition of the game and the 2009

Special Edition. No separate review for the remake is necessary, since it

changes nothing in the base game but rather just provides a complete overhaul

of its visuals, sound, and gameplay interface. |

||||

|

With so much emphasis on

the humor and general oddity, it is perhaps no surprise that the graphics in

the original game were not all that impressive — putting it mildly. For 1990,

the year when Sierra On-Line once again turned the tables with its transition

to full-fledged VGA, the quality of Secret’s

pictures looked downright antiquated even back then. The backdrops are rather

crude, detalization is kept to an austere minimum, and character sprites are

just large enough to look primitively grotesque, but not too large to look hilariously

grotesque (as in, say, Maniac Mansion

with their giantly disproportionate heads and all). In short, the graphic

aspect is suitably picturesque and serves the purpose fairly well, but a good

example of 1990’s digital artistry it is not. One curious exception to

the rule are the close-up shots of characters’ faces, starting right from the

sly, sleazy, heavily bearded old pirate Mancomb Seepgood and ending with

Elaine Marley, the love of Guybrush’s eccentric life. The original EGA

paintings by Steve Purcell were quite vivid and made good use of the limited

color palette, but it is the redrawn 256-color VGA images by Iain McCaig that

really made all the difference — the textures, the lighting, the shading, the

almost photorealistic level of detail. In fact, the faces were so realistic

that for some fans, it almost broke the immersion, detracting from the

overall goofiness, which is probably why the whole thing was scrapped once it

came to the Special Edition. And speaking of the 2009

Special Edition, this is where things really got good (as they did with

pretty much all of the LucasArts remasters, to be fair). Instead of doing

some silly thing like going 3D, the artists preserved a bit of the crudeness

of the original, but now they made it look like a feature rather than a bug —

in other words, the 2009 remaster looks all crooked, jagged, twisted, and

ever so slightly impressionistic like the overall psychological atmosphere of

the game. The characters’ faces in close-ups now look far more cartoonish, but

not old school Disney-like cartoonish as in Curse Of Monkey Island; instead, everybody receives the «angular»

treatment, which makes most of the faces look like high-class wood carvings

or something, which is weird, and weird is always good for this game. Arguably the only

«miscasting» decision made in the Special Edition concerns Guybrush himself.

In the original game, he was a rather short, pudgy, chubby little guy with a

(presumably) mischievous stare. In the SE, however, they probably tried to

match him up better with his long and lanky avatar in Curse Of Monkey Island, and the result is a thin, spiderish

sprite with frightened, deep-sunken eyes who kinda looks like he’d just

recently been liberated from Auschwitz. It is true that most NPCs in the remade version (with the exception of Meathook)

could stand gaining a little weight, but I do keep catching myself wanting to

force-feed my Guybrush all the time when I should be looking for treasure

instead. (Special mention should be

made of how the Special Edition truly respects the original game by including

a mode that lets you revert to the original graphics and interface at any

time — providing a valuable history lesson for newbie fans while at the same

time soothing the hearts of the veterans. The only downside is that the voice

acting is not carried over to the original — something the developers would

correct for Monkey Island 2). |

||||

|

This is where both the

original and the remade edition

have to be commended, for entirely different reasons. The original Secret Of Monkey Island happened to

be LucasArts’ first adventure game to feature a complete musical soundtrack,

playable in superior quality with a MIDI interface — as usual, in the

exciting Sierra On-Line vs. LucasArts race the latter kept running ahead in

terms of inventiveness and gameplay, but lagging behind when it came to

technical progress (budget, budget, budget!). Anyway, while the producers

still didn’t quite have the money to hire an established pro such as William

Goldstein (King’s Quest IV) or at

least a well-known name like Bob Siebenberg (Space Quest III), they settled on the next best thing — a Harvard

graduate by the name of Michael Land, well educated in both classical and

electronic music, who would go on to become LucasArts’ chief composer and

musical supervisor until the very end. Needless to say, he

probably would not have gone on to

become all that if his very first soundtrack hadn’t been such a masterpiece —

unquestionably the single best soundtrack in the entire series (if only

because all the other ones, one way or another, were derivative from it), and

one of the 2 or 3 best soundtracks in the history of the LucasArts studio in

general. Not only does it feature tons of catchy, inescapable, perennially

hummable melodies (above all, the classic Monkey Island Theme and the

grinning-carnivalesque LeChuck’s Theme), but its weirdass mixture of

quasi-Caribbean rhythms and instruments with slightly corny vaudeville hooks

fits the game’s general atmosphere to a tee. For instance, LeChuck’s Theme

has just a faint tinge of «ominousness» in its brass fanfare, just as the

Ghost Pirate LeChuck himself is supposed to be more of a buffoon than a real

threat. Meanwhile, Stan The Salesman’s Theme sounds like a parody of some

particularly obnoxious swaggy commercial — but played by the same phantom

pseudo-Caribbean orchestra, further adding to the sensual confusion. At the

same time, this is still a soundtrack: the most memorable themes, whisking

away your attention, occur only during encounters with the game’s characters

— the music that plays while you’re crawling through the jungle on

Mêlée or Monkey Island is more ambient in nature, enhancing your

crazy experience but never detracting from it. The Special Edition paid

proper homage to the soundtrack, re-recording everything (with live

instruments to boot!) and bringing audio quality up to fully modern

standards, also throwing up some additional SFX effects for good measure. But

the most important improvement, of course, is the addition of a fully voiced

soundtrack. Before that, the first fully voiced Monkey Island game was The

Curse Of The Monkey Island, a fantastic title in its own right but

seriously plagued by being chained to the game’s own mythology; the voice

acting was arguably its largest advantage over the two previous titles — and

now, with full voiceovers for the first game provided mostly by the same

actors who had already owned the characters in Curse, Secret Of Monkey

Island once again took center stage. Dominic Armato is the perfect Guybrush,

mixing innocence, arrogance, mischief, and hyper-activity like no one else

can; Earl Boen provides the perfectly cartoonish-evil voice for LeChuck;

Leilani Jones is the mysteriously cynical Voodoo Lady; and Alexandra Boyd was

finally able to provide some sassy character for Governor Marley (she only

got a few lines in 1997’s Curse,

what with being forced to spend most of the game in the form of a gold

statue). Everybody, including the minor characters, does a great job — and it

is arguably the voice acting, rather than the improved graphics, which now

make the Special Edition into the default version of the game, leaving the

original as more of a nostalgia package. |

||||

|

Interface The original Secret featured a fairly standard

version of the SCUMM interface: about a third of the screen was given over to

the command list (‘open’, ‘close’, ‘push’, ‘pull’, etc.) and the inventory

list, from both of which you could construct the required phrases using the

mouse or the cursor keys. The same space was used to display your dialog

options, from which you were supposed to choose the most useful one (or the

funniest one, which were quite often not the same thing). Pixel hunting was

obligatory as well, and with the graphics still not quite up to par, this

could sometimes be an unfortunate extra obstacle. The Special Edition

introduced some radical changes to the old design. The picture was expanded

to fill up the entire screen, while the main commands were now tied to the

mouse cursor — by tapping a keyboard shortcut or scrolling the mouse wheel,

you could change its shape to ‘open’, ‘close’, ‘push’, ‘give’ or whatever

else. A separate inventory window could now be opened up at will, rather than

having to scroll through text descriptions of the objects at the bottom of

the screen. Objectively, this completed transition to the point-and-click

style is better because it lets you see more of what is happening (though it

does not necessarily speed up the game, since you could use keyboard

shortcuts to select the necessary command in the original game as well);

subjectively, one can understand old veterans feel a little nostalgia for the

interface hub, but as conservative as I tend to be in these matters, there is

hardly anything I could come up with to defend it rationally. There is little to add

here, since the game is a «pure» adventure title and features no arcade /

action sequences whatsoever (in fact, one might argue that the whole

insult-based sword fight sequence is in itself a comic send-up of all digital

swordfight action à

la Sid Meier). There are some time-based actions where you have to be quick

(most notably, in the final battle against LeChuck), and there is a cool

psychedelic maze which turns out to be a pseudo-maze upon close inspection

(you cannot cross it without a navigator, and once you have your navigator,

it is no longer a true maze), but other than that, it’s just you and the

SCUMM interface all along. |

||||

|

The Secret Of Monkey

Island remains a bit of a mystery — it is a game that you

(probably) immensely enjoy while playing, but if you stop to think about why precisely you find it so

enjoyable, the answer might not come quickly, or it might not come at all. It

is clearly more than just a parody; a pure parody would never be so endearing

and cherishable. On the other hand, it is not exactly a masterpiece of the

post-modern approach — its primary audience, after all, was a teenage one

rather than an adult one, and there’s only so much witty cultural referencing

you can throw into something like this without confusing or boring your

target recipients. It does not make you care all that much about its

characters, does not offer all that much in the adrenaline thrill department,

does not provide any particular educational value... so why is it so awesome? The answer, perhaps, lies in some deep psychological area: one thing

that Secret did better than any

LucasArts game before it, heck, maybe any

game before it, is conveying that intangible spirit of total and utter

freedom and irreverence which we all crave often without even realising it.

Some formal boundaries were set here, but only to be broken at any time —

clichés busted on their asses, tropes overturned and inverted wherever

possible, genre rules ridiculed and scorned just because we can. Take a good

look back at the past 20 years or so and think on how many video games

produced in that timeframe have that absolute freedom of absurdist

story-telling that Monkey Island

delivers in spades — it is quite likely that you will see the gaming industry

moving away from that freedom rather than endorsing and developing it. In

fact, one could argue that even Monkey

Island itself eventually fell victim to the chain-setting trend, though

this is something that I would rather discuss in more detail in an upcoming

review of the third game in the series. Meanwhile, The Secret Of Monkey Island, despite being less polished and

detailed than its sequels, has the unbeatable benefit of setting its own

rules — or, rather, setting its own anti-rules — rather than following them.

And now that, in our modern age, we have been blessed with the appearance of

the Special Edition, fully updating the game’s technical side for the 21st

century player while managing to preserve and cherish the spirit of the

original product, there is no reason whatsoever to stay away from one of the

funniest games of all time unless you only play Animal Crossing or whatever. |

||||