|

|

||||||

|

Studio: |

Sierra

On-Line |

|||||

|

Designer(s): |

Marc

Crowe / Scott Murphy |

|||||

|

Part of series: |

Space

Quest |

|||||

|

Release: |

October 1986 |

|||||

|

Main credits: |

Programming: Sol Ackerman, Scott Murphy, Ken Williams |

|||||

|

Useful links: |

Playthrough: Part 1 (60 mins.) |

Part 2 (57 mins.) |

|

|||

|

In 1986, with King’s

Quest firmly established as a permanently running series and already

aiming for extra depth and scope with its third installment, To Heir

Is Human, Sierra made its first, still quite tentative, move into the

sci-fi market. The punch came from two of Sierra’s residents, Mark Crowe and

Scott Murphy, the former of which had already spent a lot of time working on

previous games as graphics designer, while the latter was a relatively new

acquired programming talent. Both had already worked together on Sierra’s

fun reimagining of Disney’s The Black Cauldron, and, in the process,

formed a partnership which is still fondly remembered today by fans around

the world — the Two Guys From Andromeda, adopted fathers of Mr. Roger Wilco,

the well-distinguished space janitor from outer space. Although

Space Quest was

hardly the first sci-fi game on the market (naturally, the very status of the

computer as a hi-tech gadget presupposes that, from the very beginning of the

industry, sci-fi themes would be firmly integrated into computer lore), but

it was the first text-and-graphic adventure game to share

the honour. And, like almost any revolutionary breakthrough, in retrospect nothing

is easier than picking on its numerous flaws. With drastically underwritten

characters, laughably short running time, thoroughly imbalanced puzzles, it

is quite a rough beginning. As with King’s Quest, it ultimately took

the authors at least a couple more efforts to get all of it right and

smoothly running. However, back in 1986 everything was so novel and exciting

that the game quickly caught on in sales with the first installments of King’s

Quest (100,000 sales at the time

was an extremely big achievement). The idea itself was simple

as pie. As Roger Wilco (more precisely, as a self-styled character: not until

the third game does the name «Roger Wilco» become resident, independent of

the player’s choice), you are working as a janitor aboard some space craft

which houses some fabulous gizmo called The Star Generator which is kidnapped

by aliens called Sariens whose ship must be hunted down and destroyed in

order to save the human race — not a particularly innovative concept in the

annals of sci-fi history. But one thing was established here once and for all:

the plotline would always be secondary to the atmosphere, the imagery, and,

most important, the unique brand of sci-fi humor pioneered by the Two Guys. |

||||||

|

Content evaluation |

||||||

|

The plot of Space Quest is so simple that I

seriously suspect it was cobbled together in about five minutes already after

most of the settings, images, and jokes had been introduced. Having never

been much of a sci-fi buff, I cannot tell to what exact degree (100% or, say,

more like 99.5?) all the main ingredients have been hobgoblinned from

existing paperbacks, comic books, movies, and Star Trek re-runs,

but arguably for each element in the game you can still find a couple dozen

possible prototypes. For all their inventiveness, the Two Guys never tried to

step into the shoes of Clarke or Kubrick; their object was the cheap, trashy

version of sci-fi, and, come to think of it, they did not have much choice — ever

tried making a best-selling computer game out of A Space Odyssey?

Well, there you go. In the end, the plot’s

saving grace is its humor aspects. Where Roberta Williams kind of walked the

line between lightweight and serious (her Graham and Alexander might

sometimes get into comic situations, but at the end of the day they were

still your basic heroic types), Mark and Scott plunge head first into goofy,

whacked-out parody. To begin the begin, your «(anti-)hero» is a janitor — and

not a very good one at that. Thus it is already ironic that, for such a clutz

in dayjob terms, he is saving the world on a more frequent basis than James

Bond. Next, much of the time the game is advanced through decidedly non-standard

solutions — including, for instance, one of the oddest ways ever invented to

dispose of a huge carnivorous monster and an even odder method of

self-disguising in order to infiltrate the enemy’s ranks. And... and... ...well, the real problem

here is that it is hard to think of much else since the game is so gruesomely

short. All of it, except for the outro, takes place in but three different

locations — two spaceships and a large planet mostly filled with yellow sand,

brown rocks and purple skies. You escape from one ship, find a second one,

then infiltrate a third one, and that’s about it. When the game is so short,

it cannot help but convey the feeling of merely a preparation stage for

something bigger and better, and this serves as an excuse for all kinds of

plotholes and goofs. Why the heck was the Sarien Spider Droid dropped on

Kerona? How did Roger’s ship manage to approach the Deltaur without being

spotted? What about the strange lack of language barrier between Roger and

the Sariens? But ultimately none of this really matters, because if the

entire game is just like a test stage, well then, test stage it is. |

||||||

|

The Space Quest series take a specially twisted sort of pride in the

illogical nature of most of their puzzles — this is, after all, a spoof, and

spoof games are supposed to have spoof puzzles. Consequently, I have no

problem with the idea of dispatching a monster in a way you are least likely

to think of when faced with the necessity of dispatching a monster. But

regardless of these general considerations, the fact remains that The

Sarien Encounter does not have a fairly good balance of complex vs.

simple puzzles. Thus, the entire first section (on board the Arcana) is

fairly trivial, provided you know the basic rules of Sierra game playing

(leave no stone unturned, etc.). Then you are on Kerona, and whoosh, the

difficulty level soars so high you can get stuck for days. Then you are on

your way to Ulence Flats, and back to mostly trivial again — with one

exception (concerning learning your next destination). In brief, most of

the puzzles are obvious, but a few are unjustifiedly complex. Of course, that

is the usual bane of early Sierra games, when the art of puzzle-making was

still in its initial phase, but in any case, the first Space Quest is

probably not a game you shall fondly remember in terms of brainstorming. In

one case, finding the right solution depends on whether you are able to

discover a vital object that is, quite literally, not seen at all on

the screen — you all but have to guess

it is lying there. In another case, it depends on whether you are able to

repeat a certain action multiple times when you really have very little

incentive to do it. To top it all, it is impossible to get 202 out of 202

possible points without indulging in a couple Easter Egg-like activities of a

hilarious, but completely random nature. [On the positive side, this

certainly does add to the game’s replayability, but in a rather cruel way at

that.] Sierra’s regular bane,

arcade sequences, is also a serious pain in the ass. At one point, you are

required to navigate your vehicle ("sand skimmer") through a set of

rocks — a sequence that is as poorly animated as it is poorly controlled. (A

very similar arcade exists in Leisure Suit Larry III, but at least

it is better programmed in that game). The player’s interaction with the

Sariens is mostly limited to a series of «quickdraw» battles where the main

point seems to be that you have to press the fire key before you

can even make sure that an enemy is present, otherwise you’re toast. And then

there is the slot machines sequence — aaarrgh! Sometimes it seems to me that

the main point of having slot machines in so many Sierra games is to teach

the player how to operate in Quick Save / Quick Restore mode. At least

in Leisure Suit Larry you have the «thinking man’s

alternative» to play some blackjack, but apparently in Ulence Flats, cards

are strictly off the table. |

||||||

|

One thing to be said in

defense of the Two Guys is that they certainly did their homework on outer

space mythology. For a game with such rudimentary graphics and such a limited

plotline, a lot of effort went into making the whole thing believable. When

you’re in space, you’re in space, and when you are suffocating from thirst

amidst sandy dunes, well, that is exactly what you’re doing. Graphics, text

information, and characters’ activities are all relatively detailed and

well-thought out. The major part of the

atmosphere, though, is striking a careful balance between the horrid and the

hilarious. On one hand, life in space ain’t for the faint-hearted. Danger

lurks on every corner and sometimes between corners. You absolutely never

know when and how you might walk into a deathtrap. Much to the Two Guys’

honor, being careful in this game actually pays off: most of the times, if

you take the effort to look around and weigh your options, you can prevent

yourself from being mashed, smashed, and pumped. Still, unless your sixth

sense is truly overdeveloped, it is hardly possible to know everything

beforehand, and you will definitely get a couple heart-jumps as the game goes

on (heck, you might even get them in this modern age — a shock is still a

shock even when it’s in 16 colors). On the other hand, all of the

«horrid» elements are always compensated for with fun ones. The number of

different ways to die is already large enough to warrant intentional attempts

at suicide — although the deaths are only occasionally accompanied with funny

messages, and never with funny pictures («Space Quest Deaths» wouldn’t really

become a classic trademark until the third game in the series). Monsters,

rather than truly scary, are either weird (like the spider droid) or

hilarious (like the Orat). And even the superficially impenetrable Sariens

turn out to have a goofy side about them if you stay on board their ship long

enough to find that out. In somebody else’s hands, this mix of humor and

horror would be frustrating, but the Two Guys craft it in such a way that you

never really find yourself torn between the two sides. |

||||||

|

Technical features |

||||||

|

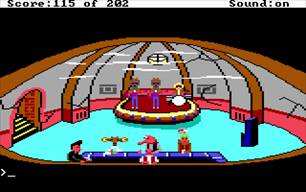

Since this is the earliest

game in the series, graphics are obviously poor even for AGI standards. The

sprite of Roger Wilco can hardly be looked upon without shudders, and many of

the locations are illustrated in a very sketchy way. The contrast between the

overwhelming yellow of the sands of Kerona, the overwhelming brown of the

rocks of Kerona, and the overwhelming purple (sic!) of the skies of Kerona

makes for a nice first impression — one of isolation and emptiness — but soon

enough you begin to wonder if the real reason behind all the simplicity wasn’t

an overwhelmingly tight budget. Ship interiors mostly consist of look-alike

corridors and identical doors, and the only place, in fact, that looks lively

at all is the bar at Ulence Flats. On the other side, the few

screens that Marc Crowe took the time to develop do show dedication to the

craft. Technical areas, computer panels, general spaceship design — all is

done with attention to detail that was unprecedented for 1986. The best views

are close-ups, of course, such as when Roger is sitting in the shuttle

cockpit, but there are also some nifty space panoramas as well.

Interestingly, some pictures are there just for the fun of it: for instance,

there is a section where, in true Star Wars mode, you are

going into an asteroid field, and you might probably think that it’s another

one of those damn arcades where you will have to evade nasty gray rocks, but

it isn’t — it’s just a few seconds of «AGI cinema» that’s done nicely enough

for you to drop your controls and just enjoy the sequence for a few relaxed

seconds. Special kudos goes to funny

cameo appearances by both the Blues Brothers and ZZ Top in the Ulence Flats

bar; although sprite animation is easily the weakest thing about those early

AGI games when it comes to graphics, these particular ones, with their

thoroughly pixelated sunglasses and beards, are easily recognizable to anyone

who has ever seen the real thing. Apparently, though, the ZZ Top appearance

was not taken lightly by the band itself, or their management, leading to a

bit of trouble with Sierra — as if, for some reason, this appearance could

have any negative impact on their career! (To be more precise, the actual trouble

may have concerned the remade VGA version of the game rather than the

original). |

||||||

|

Sound Well... the game does mark the first appearance

of the famous Space Quest Theme, arguably Sierra’s

most recognizable tune after Al Lowe’s Leisure Suit Larry theme. Other than

that, it doesn’t mark much of anything. Again, the Ulence Flats bar is the

best place to appreciate the unlimited possibilities of the PC speaker, as it

tries to emulate some sort of sci-fi age synth-pop theme for the alien band,

something good-timey and crazy (namely, ‘I Can’t Turn You Loose’) for the

Blues Brothers, and something with a supposed rock beat (namely, ‘Sharp

Dressed Man’ — specially dedicated to Mr. Roger Wilco!) for ZZ Top. The

effort is commendable, but you really have to go out on a

limb these days to fall for its charms. Sometimes the sounds are an

awful distraction — for instance, during the atrocious rock-avoiding arcade

sequence, which is made even more unbearable as the speaker drives you crazy

while you are trying to figure out just how often it is necessary to push the

arrow keys in order to restore the game twenty times instead of fifty. Droid

and emergency beeps and bleeps on board the Sarien ship are equally ugly. In

the Kerona caves you are told about how the sound of dripping water soothes

your nerves, but if it is my nerves we are talking about, it merely gets on

them. In short, you’re not missing much — in fact, you’re only gaining — if

you just play through the game with the sound turned off, turning it back on

briefly for a laugh during the bar scene. |

||||||

|

Interface Space Quest’s status as the first

tentative step into something new and unknown is perhaps most evident in its

parser system. Compared to King’s Quest III, marketed at around

the same time, it definitely takes a step back in terms of possibilities. For

instance, once again you can’t just type ‘look’ in order to get a general

overview of your surroundings (although ‘look around’ does work, for some

reason). The number of possible options to be performed with various objects

is drastically limited, in fact, the number of objects themselves is so small

that most of your time will be spent receiving messages like ‘I don’t

understand’ blah blah (and not even funny messages at that — the received

answers, as compared to even already the second game in the series, are

usually quite straightforward and boring). If you type ‘look at the table’,

you are most likely to get a response like "You see a table". Arcade sequences, as has

already been mentioned, are also a pain in the neck. The only point of the

slot machine experience is to make you suffer (as in, ‘I am supposed to be an

intelligent being of the planet Earth... so why the hell am I spending hours

of my precious time spinning a stupid set of cherries and diamonds when it

isn’t even for real money?’), and don’t get me started again on

the sand skimmer sequence. In its place, they might have added a little extra

spaceship-controlling sequences, which are, however, reduced here to

rudimentary commands like ‘pull throttle’ and, oh yes — drumroll! — ‘push button’. |

||||||

|

The first Space Quest is

not as perfect an introduction into the world of Roger Wilco as it could have

been — it is, quite honestly, a rushed and semi-finished project, which might

have something to do with (probably) lacking the same reverential technical

support as was characteristic of Sierra’s main golden-egg hen at the

time, King’s Quest. (In this respect, it is arguably one of the

very few games in the Sierra canon where the later remade version seriously

improves on the original). It is still worth playing through, though, at

least once, if only to see where it all begins and experience firsthand just how

much it has all changed since then. And it is also impressive that, despite

all of its numerous limitations, the game still captured a solid part of its

potential audience in its time, and, more importantly, that Ken Williams gave

the Two Guys the green light on further proceedings — ones that helped

eventually make Space Quest into a national phenomenon. |

||||||