|

|

||||||

|

Studio: |

Sierra

On-Line |

|||||

|

Designer(s): |

Marc

Crowe / Scott Murphy |

|||||

|

Part of series: |

Space

Quest |

|||||

|

Release: |

November 14, 1987 |

|||||

|

Main credits: |

Programming: Sol Ackerman, Scott Murphy, Ken Williams |

|||||

|

Useful links: |

Playthrough: Part 1 (66 mins.) |

Part 2 (63 mins.) |

|

|||

|

In 1987, Space Quest became Sierra’s first

franchise to break the hitherto unchallenged monopoly of Roberta Williams’ King’s Quest on the sequel trade — a

fact more easily explained by the impressive commercial success of the

original Space Quest than by the,

no doubt overwhelming, personal charisma of Scott Murphy and Marc Crowe. It

seemed like adventure game fans, many of them natural sci-fi geeks, were

eagerly willing to accept Roger Wilco, space janitor extraordinaire, into

their hearts, and so the Two Guys From Andromeda set out to oblige. However, compared to the

first game, Space Quest II can

hardly be said to represent a giant leap for mankind. Much like King’s Quest II next to its

revolutionary predecessor, it essentially ends up offering more of the same,

with cosmetic improvements on all fronts — more content, better dialog, more

clever parser, minor improvements in graphics and gameplay — but no major

broadenings of the creators’ vision. It is a good kind of sequel, relying

more on the power of creative imagination than on in-jokes, running gags, endless

navel-gazing self-references and stale humor, but it is still very much a

typical sequel in nature, and also one that somewhat downplays the Two Guys’

usually acute flair for satire and parody. Once again, Roger Wilco is

supposed to save the world — this time, from a clichéd megalomaniacal

scientist planning to invade Earth with millions of cloned life insurance

salesmen — and once again, his good deeds largely go unnoticed by the

galaxy’s inhabitants, even if adventure game fans did buy the game in droves

and turned it into yet another bestseller for Sierra, thus ensuring the

future of the series. In short, we do have the success of Space Quest II to thank for the

appearance of Space Quest III,

which brought a whole new life to the franchise. But on its own, this title

is relatively lackluster, though it still has its fair share of hilarious

moments. |

||||||

|

Content evaluation |

||||||

|

The main premise of Space Quest II is actually more

intriguing than that of its predecessor. Captured by the archvillain Sludge

Vohaul (apparently an evil clone of the Star Generator’s benevolent architect

Slash Vohaul from the first game, though I do believe this explanation still

involves quite a bit of retconning), Roger Wilco is introduced to his newest

heinous plan of bringing the world to its knees — mass-launching the invasion

of an army of genetically engineered life insurance salesmen — before being

sent off to die in Vohaul’s mines on the nearby planet of Labion. This is cool and all, but,

unfortunately, the idea of salesman clones is not explored any further (in

fact, if you do not screw things up, not a single one of these guys even gets

the tiniest chance of leaving his pod before they are all melted down).

Instead, it is all about being stranded on Labion, a planet where each and

every step breathes danger, and about making your way back to Vohaul’s ship,

where you have to do what you have to do. The Main Story — Wilco’s conflict

with Vohaul — takes about 10% of the game and involves precisely one puzzle

(and a very uncomplicated one at that, at the heart of which lies the

challenging task of pressing a button). Everything else is the journey,

consisting of disconnected strings of little accidents — Roger Wilco gets

caught by a feral hunter; Roger Wilco is cornered by the Labion Terror Beast;

Roger Wilco has to escape another of Vohaul’s traps by means of a roll of

toilet paper, etc. — and while some of these vignettes are fun, in the end it

still seems as if the game’s authors were just making this stuff on the spot,

without any general strategy for the game other than «Vohaul must go». As far

as Space Quest games go, the second

one has easily the thinnest storyline of them all. |

||||||

|

You would probably think

that if the game places more emphasis on the micro-management of current

problems than it does on the general plot development, then at least the

specific puzzles could be a major improvement on the previous game.

Unfortunately, this is not the case. Most of the problems that Roger has to

solve along the way fall into two distinct categories: (a) laughably trivial

and (b) frustratingly impossible, at least by modern gaming standards (old

school adventurers were inarguably a much tougher breed than latter day

snowflakes, heh heh). Serious trouble does not even start until about 1/4

into the game when Roger gets into the swamp area — and then prepare to get

screwed if you do not hit the right area of the screen. Needless to say, in

classic Sierra fashion there are also a few ways to get hopelessly stuck by

forgetting to pick up an important object you never knew could be needed in

the first place (though not a lot this time). Moon logic hits hard in a

couple of places, most notably in the situation where you have to pacify the

Labion Terror Beast — although, to be frank, this is arguably the single most

hilarious puzzle in the game, worthy of appearing in a LucasArts product;

also, if you get stuck here you actually get the alternate option of simply

rushing past the Beast, at the cost of a few points and a good hearty laugh. Some

tough challenges also await you inside the winding corridors of Vohaul’s huge

space station — involving a fairly unorthodox use for a toilet plunger, among

other things. That said, on the whole the puzzle design is okayish: not too

great, not too terrible... in other words, nothing particularly memorable

except for the Labion Beast thing. Where the game does become terrible is in its abuse

of the maze-type stuff. To compensate for the relative lack of stairs from

which you can tumble to your death, the Two Guys decide that Roger must

demonstrate true wonders of agility and ingenuity — first, by having to

navigate between the highly sensitive tendrils of a giant flesh-eating plant

(where each wrong pixel results in instant death), and next, by being forced

to blindly explore the corridors of an underground cavern where a single

wrong turn may easily turn you into a happy meal for the cave’s squishy

owner. There are other challenges, too, which involve finger dexterity, but

these two were somehow enough to turn Space

Quest II into one of my most disliked Sierra games from the early AGI

period (God, I hate mazes!). |

||||||

|

Perhaps the worst problem

of Space Quest II is that, less

than any other game of the series, does it actually feel like an authentic Space Quest game. It is (almost)

always recommendable to think out of the box and break conventions, but I am

not sure that this is quite what the Two Guys had in mind when they designed

the planet of Labion which, honestly, feels more like it belongs in a King’s Quest instalment, what with the

little red furry guys roaming (like elves or dwarves) in the underbrush, or

the various other cutesy or dangerous representatives of the local flora and

fauna. About half of the game is spent in those jungles, which may be well

illustrated and all, but provide few opportunities to flaunt the classic Space Quest humor — and, to make

matters worse, apart from the first and final conversation with Vohaul, Roger

spends the entire game virtually alone:

no talking companions along the way, no drunken barroom customers, no weird

robots with personality crises, heck, even Vohaul’s security guards are only

there to be able to quickly drop dead. Things get even weirder in

the second part of the game, when you have free roam time to navigate

Vohaul’s huge space station — which, as it turns out, is also completely

empty, apart from an undistinguished alien or two locked deep inside a toilet

stall. Perhaps the emptiness was supposed to feel intimidating; in reality,

navigating those long empty corridors quickly becomes a bore (at best), or a

hassle (at worst — whenever you are pursued by a security droid or an

automated vacuum cleaner, neither of whom are willing to stoop so low as to

exchange a word or two of greeting with you). Eventually, Space Quest II becomes more of a Silent Quest, with its own odd feel that may or may not be a good

thing. Personally, I far prefer the loneliness and silence of something like

the garbage freighter at the beginning of Space Quest III, because that

environment actually has a distinctive sci-fi feel to it, with space debris

and intimidating robotic structures all over the place. Here, though, it’s as

if at least parts of this game were supervised by Roberta Williams — you half

expect King Graham or, at the very least, Rumplestiltskin to jump out of the

nearest bush. The funny thing is, there are actually more ways to die in the

jungle of Labion than there are in the garbage freighter, yet because of all

the little furry friends, the environment of Labion feels much less scary. I

sure wish there had been a moment for the Two Guys, sometime during

development, to sit back and take an outside look at what they had created —

but things were probably in a rush. |

||||||

|

Technical features |

||||||

|

At least on the technical

front, Space Quest II consistently

improves on the first game in just about every respect, starting with the

graphics: although the AGI system remains essentially the same and so do the

color palettes, resolutions, and sprite animation systems, Marc Crowe clearly

put in more effort to make stuff look as realistic and detailed as possible.

Compared to the relatively bare-bones detalization of locations like the

desert planet of Kerona or the Sariens’ commanding ship, Labion and Vohaul’s

baze are positively brimming with detail — more rocks, more plants, more tiny

bits of animation which make the screen come to life; notice, for instance,

the neat trick of making the firelight from the feral hunter’s lit bonfire

reflect on the hunter himself as he is sitting outside Roger’s cage, or the

(still rather hilarious!) befuddled look on the Labion Terror Beast’s face as

he scratches his head in utter bewilderment over the challenge issued by

Roger. Special care was taken to

depict and animate Vohaul, the first and main archvillain of the series — his

closeup impression in the game’s prologue was probably unforgettable back in

the day, bulky belly, creepy facial expressions and all (too bad there was no

budget to come up with a proper representation of his downfall at the end of

the game). We also get to see Roger Wilco himself in close-up for the first

time ever, as he tries to pilot the kidnapped shuttle away from Labion — if I

am not mistaken, this is the first ever close-up portrayal of the protagonist

in a Sierra adventure game, and although, for understandable technical

reasons, it gives Roger a somewhat cruder and burlier appearance than he

would have in the next two games, it still counts as an achievement. Other

than that, there is little to talk about when it comes to graphics in this

game. |

||||||

|

Sound Not much to speak of,

either: the game seems even skimpier on sound than its predecessor — the only

music is the already familiar Space Quest theme at the beginning and in the

end, as well as a single bar of «Vohaul’s Theme» announcing the entrance of

the archvillain (twice). Sound effects are limited to annoying PC speaker

alarm bells, gunshots, occasional nature effects (waterfalls, etc.), and the

tornado-like behavior of the Labion Terror Beast (very annoying: please stop him as quick as possible!). |

||||||

|

Like

the first game, Space Quest II

features quite a rudimentary interface — unlike Al Lowe, the Two Guys never

thought much about tinkering with the menu bar — and only marginal upgrades to

the parser system (at least now you can simply type in look to get a

general account of your environment). Also, the obligatory answer to fuck and shit has been

changed from the oddly formulated "A mind is a terrible thing to

waste" in Space Quest I to the

more comprehensible, though fairly boring "Would you want your mother to

hear you say that?" in Space

Quest II (implying that you would still have to probably be a teenager to

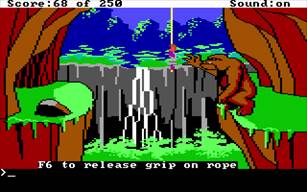

play the game). With arcade sequences

largely eskewed in favor of mazes (ugh!), the closest you get to good old

school gaming is in a brief sequence where you have to swing on a rope to get

to one side of a chasm while trying to avoid a hungry monster on the other —

fairly trivial, though you might still die on the first couple of tries

before you figure out the correct timing. Other than that, Space Quest II is about as hardcore

as puzzle-based adventure games ever get. |

||||||

|

As you can already tell, I have never been too fond of this game,

though I certainly accept it as a legitimate part of the Space Quest canon.

It simply feels too short and too rushed — something you could probably

disregard if this were the first game in the series (just because its main

function would be to conduct the first round of world-building), but even King’s Quest II, for all its

similarity to the first game, felt expansive and boundary-breaking. Space Quest II does introduce you to

the series’ greatest villain, but that’s about all it does. Only the relative

scarceness of well-designed adventure games at the time and Sierra’s overall

reputation can explain the commercial success of the game — fortunately,

contemporary praise never went that much to the Two Guys’ heads, and I

surreptitiously hope that they themselves were able to reflect on all of the

game’s shortcomings, which would largely be corrected for the

masterpiece-to-come, Space Quest III:

The Pirates Of Pestulon. |

||||||