|

|

||||||

|

Studio: |

Sierra

On-Line |

|||||

|

Designer(s): |

Marc

Crowe / Scott Murphy |

|||||

|

Part of series: |

Space

Quest |

|||||

|

Release: |

March 24, 1989 |

|||||

|

Main credits: |

Programming: Ken Koch, Scott Murphy, Doug Oldfield, Christopher

Smith Music: Bob Siebenberg |

|||||

|

Useful links: |

Playthrough: Part 1 (64 mins.) |

Part 2 (65 mins.) |

|

|||

|

This review should probably

come with a disclaimer stating that Space

Quest III was, in fact, the very first Sierra adventure game that I

played and that this may have something to do with the fact that it has since

become ensconced in my brain as one of the best adventure games of all time, period.

Then again, happy coincidences do

happen, and Sierra On-Line was on a

major roll in the late Eighties, and each time I happen to replay this game I

still find joy in so many of its aspects that this is no more pure nostalgia

than, say, listening to an ABBA album from my deepest childhood. More like I

was just incredibly lucky. Anyway, in my previous

review I did mention that the second game in the Space Quest series was not all that hot, looking and feeling

rushed and not really matching the imaginative and comic standards set by the

first entry; nevertheless, it still found critical and commercial acceptance,

largely through lack of any serious competition — almost any Sierra adventure

game in 1987 would have. Fortunately for the fortunes of the Space Quest

saga, technical progress came along and saved the day: advances in processing

power, graphic resolutions, and digital sound technology led to a new

generation of adventure games, kickstarted with King’s Quest IV, and with the development of Sierra’s Creative

Interpreter everybody at the company had to step up their game or get off the

ship. The Two Guys From Andromeda deemed themselves worthy of the challenge,

and delivered a brand new chapter in the adventures of Roger Wilco, space

janitor — and when I say «brand new», I actually mean what I say, rather than

just stick with an obvious cliché. That the game would be a

major technical improvement over the first two was understood — better

graphics, addition of a musical soundtrack, and a vastly improved parser

system were all Sierra’s trademarks of that era — but the important thing is

that along with technical improvements came substantial ones. Not only did

Roger Wilco finally gain some personality in the game, becoming an iconic

protagonist, but so did his creators, the Two Guys From Andromeda, by daring

to put themselves in the game as its chief McGuffin. For the very first time,

the game got a truly original story, an actual solid plot that managed to

combine intrigue and suspense with acid satire. And, finally, hard as it is

to explain, the game — and the entire Space Quest universe with it — came to life. This was not just an

adventure game in which you had to crack a few puzzles, get from Point A to

Point B and then to Point C, save the world and go home: Space Quest III introduced a parallel reality in which you

actually wanted to spend time, like in a good RPG (OK, I know for sure I actually did, whereas all I wanted

on the planet Labion was to get the hell outta there as soon as possible).

And although the game had not yet slipped into the comfortably winning

formula of the later, talkie-era Space

Quest games, I find this to be the same kind of refreshing blessing which

also made Leisure Suit Larry II

from the same era into arguably the best Larry game — with the creators not

yet obsessed with their own mythology and not yet chained to their own inside

jokes and running gags. |

||||||

|

Content evaluation |

||||||

|

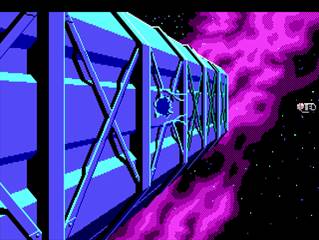

Here is the catch: Space Quest III tells the single best

story in all of Space Quest

history, and yet in so many reviews of the game you shall find that the main

complaint is always the same — the game has almost no plot! Yes and no, no

and yes. The thing is, the «plot» is actually not introduced until about the

middle of the game. Before that, Roger Wilco largely wanders around seemingly

without purpose — first, inside the bowels of a huge interstellar garbage

freighter, where his little escape pod has been sucked in as a piece of space

debris; later, once he escapes the freighter, amidst the endless purple dunes

of the lonesome planet Phleebhut, where his ship has brought him for no

particular reason. It is not until a brief pit stop at the Monolith Burger

(«Over 20 Gazillion Served Galaxy Wide!») that Roger, seemingly by sheer

accident, is able to discover the reason fate has landed him in this precise

quadrant, and proceeds to fulfill his mission — free his own creators, the

Two Guys of Andromeda, from the pesky hands of the (software) Pirates of

Pestulon and their terrifying leader, the 14-year old Elmo Pug. This is certainly quite

different from the first two games, where your purpose in life was clearly

established just a few minutes into the game — and, of course, in both cases

it had to do with saving the world from evil guys. If you ask me, though,

saving your own authors from evil guys is a far more cool and creative

purpose, not to mention one free of megalomaniacal clichés.

Furthermore, if the previous plots were in themselves just comically enhanced

facsimiles of every single cheap sci-fi thriller ever written, The Pirates Of Pestulon is the first

(and only) game in the series whose chief satirical target is not so much the

actual field of science of fiction as it is the growing software industry —

the «Pirates» in question are, in fact, software

pirates, running a huge underground organization which kidnaps talented

programmers around the world and exploits their talents for the benefit of

their young and insolent boss, Elmo. (There is a scene in the game where

Roger witnesses ScumSoft executives in action, as they walk around tiny

cubicles stuffed with programmers, cracking whips over their heads — no

better metaphor could be imagined for the state of the software industry, and

I suppose that to a large extent it is just as relevant today as it was back

in 1989). But while there most

definitely is a plot, it is indeed

also true that you have to spend a large part of the game (which is in itself

relatively short) wondering when that plot is going to manifest itself — and

it is perfectly all right. Because in addition to having one of the most

original and biting plots in early adventure games, Space Quest III is also one of adventure gaming’s earliest

experiments in «open world-building». As soon as you get your ship and escape

from the freighter, you are free to go anywhere you like — and even if

«anywhere» only means three or four different locations, it still makes a

huge difference from the strictly linear progression of the first two Space Quests, or even from the

open-world ideology of the King’s

Quest series, where you were also free in your movements but the entire

world was just one huge territory. Space

Quest III actually gives you free rein to travel through space, landing

on different planets, exploring them one after another, returning to old ones

once you got bored with new ones — it creates a truly immersive experience which was sorely lacking in the previous

games, and that is well worth a temporary lack of a storyline, I think. Finally, Space Quest III has probably the most

inventive and satisfying conclusion to a Space

Quest game ever — tying up loose ends by providing a concise and clear

answer to the question of how the heck were the Two Guys From Andromeda able

to end up as programmed characters in their own game, and leaving things

wrapped up well enough to not require a sequel, but open enough to produce

one if necessary. (Unfortunately, the next three games in the series left way

too many questions open for fans to be satisfied). Everything here is on a

small scale — no giant end-of-game explosions, no saving the world, no huge

award ceremony — but that small scale is precisely what makes the refreshing

difference. |

||||||

|

Like everything else,

puzzle design has been vastly improved in Space Quest III. First, because of the quasi-open-world setting,

there are very few opportunities to get hopelessly stuck — if you forgot to

obtain a vital object on one of the planets before moving on, you can always

go back and retrieve it at any time. Second, the «moon logic» situations of Space Quest II have pretty much been

wiped out: each single action that you have to perform is fully rational and

may be deduced with relative confidence. Some progression is achieved through

accidents, but even these accidents are the results of perfectly reasonable

actions, such as ordering and consuming a meal at the Monolith Burger or

shopping at the souvenir shop on Phleebhut. There is exactly one moment in the entire game when I

remember getting frustrated — after getting mugged by a huge rat in the

bowels of the garbage freighter —what happens after that makes very little

sense and is never properly explained... but one illogical situation in a Sierra adventure game is still a

record of sorts. As was already typical of Sierra games,

some of the challenges have multiple solutions — well, actually, in this case

only one challenge (overwhelming

Terminator Arnoid) has properly multiple solutions, but both are equally

complex and require a bit of creative thinking (as opposed to the «trick the

rat and win some points» vs. «give it some of your treasure and lose points»

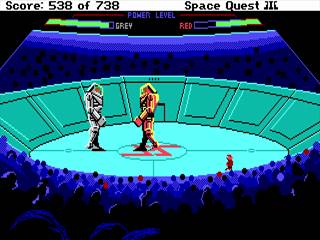

dilemma of the previous generation). A few are based on timing (i.e. standing

around and waiting for something to happen), which is never a good thing, but

at least nothing ever depends on random encounters (the bane of early King’s Quest games). There are also several arcade

sequences, but — surprise surprise! — they totally make sense and are even

reasonably enjoyable. At the end of the game there is a monumental robot

battle (the «Nuk’em Duk’em Robots», hilariously preceding Duke Nukem by a

good two years), followed by a frenzied shootout with some of ScumSoft’s

fighter ships sent in pursuit of Roger: both require very modest technical

skill from the player and are won more through intelligence than finger

nimbness (such as not forgetting to set the ship’s speed to Attack before the

battle!). The single most questionable and often criticized challenge is the

«Astro Chicken» arcade that you absolutely have to play in order to set the

plot in motion — but (a) you do not even need to win it in order to advance

(though you do deprive yourself of a nifty amount of points if you keep

losing); (b) most of the time, you can win by holding your finger on one

single key (UP); (c) the Two Guys eventually apologize for the idea by

lambasting themselves at the end of the game when offering their programming

services to Ken Williams («What are your credits?» – «Ever heard of Astro

Chicken?» – «No» – «Good!»). Anyway, this is one of the very, very few Sierra

games in which the incorporated arcade sequences will probably not piss off

adventure gamers too much. |

||||||

|

Space: the final frontier.

This is the first game in the series which totally and utterly feels like a Space Quest: even when you are not

spending time sitting in the cockpit of your ship or zipping between planets

at light speed, the game almost never lets you forget about the vastness of

the universe. There’s the huge garbage freighter, full to the brim of various

space garbage and rusty remains of all types of spacecraft. There’s the

lonely planet Phleebhut, consisting of endlessly stretching pink dunes and

dark horizons with thunder and lightning as the only thing to break up the

monotony. There’s Monolith Burger, a tiny fast-food dot in between the

endless stars. There’s the volcanic planet Ortega, consisting of a bunch of

rocks in pools of lava, above which there is still nothing but the starry sky

— and the moon of Pestulon, which you can watch through a telescope. It is

not until you descend into the cramped underground bunkers of ScumSoft that

you, very temporarily, lose touch with the starry skies — but not for long. Just like in Space Quest II, this vast space is

often way too lonesome — nary a living soul in most of the locations you

visit — but in this case, the loneliness comes across naturally, since the

planets in question have harsh conditions (Phleebhut is a near-constant death

trap, with lightning bolts, giant snakes, and venomous scorpazoids haunting

your every step; Ortega generates way too much heat to be survivable without

special equipment). On the other hand, you do encounter colorful aliens from time to time, such as the

unforgettable junk dealer Fester Blatz and a whole crowd of predictably

ridiculous aliens in the Monolith Burger (though, admittedly, most of those

guys do not have much to say other than «Quit crowding JERK!»), and these places provide a nice and

relieving contrast with the dangerous empty spaces all around. As expected, death follows you

everywhere, but almost never in a ridiculous manner — if something looks like

a potential threat, then it most likely is

a threat and you should stay away from it, but Fester Blatz is not going to

gun you down for shoplifting, and even the angry guy in the adjacent airlock

in Monolith Burger dispatches you for good only if you attempt to hijack his

ship twice in a row. Most of the

time you will probably not so much be running away from death as craving for it, just to watch all the

gory splatterfests and read all the hilarious messages that the Two Guys have

in store for you — but sometimes the situation does get tense, most obviously

when you are on the run from the invisible Terminator Arnoid or only have a

limited time to get inside ScumSoft before the guards take you down with

their terrifying Jello guns. However, humor is just as all-pervasive

as terror, be it on the menu of the Monolith Burger («Would you like some

Space Spuds with that?»), on the back of the postcards in Fester’s shop

(«Arrakis holds many delights for the adventurous vacationer... nothing can

compare with being crushed by a sandworm»), or in the obscure graffiti in the

depths of the garbage freighter («For a good time, don’t call HAL!»). The

jokes are funnier than they have ever been, and with the deaths gorier than

they have ever been, Space Quest III

delivers a juicier experience on all counts. At the same time, most of the

jokes still target pop culture, sci-fi clichés, and crass commercialism

rather than the protagonist — by the time of Space Quest IV, too many of them would be insultingly

self-referential, but in this game, Roger Wilco is actually treated with a

modicum of respect: he is a simple, silent, relatively witty and agile protagonist,

almost a space cowboy rather than a space janitor, and this creates a subtle

special bond between the player and the controlled sprite on screen, a bond

that would be hard to replicate in subsequent games just because Roger would

be much more of a «dork» with whom the player would probably not want to

identify. Here, it is all done just about right. |

||||||

|

Technical features |

||||||

|

Being the first (and only) Space Quest from Sierra’s second

generation (1988–1990) of adventure games, the third entry in the series

makes a predictably huge leap forward in terms of graphics, with increased

resolutions and larger color palettes; at the same time, Marc Crowe, like

William Skirvin in contemporary King’s

Quest and Larry series, goes

for a relatively austere look when it comes to pixel-populating the screen —

meaning that the game still looks extremely well today even when stretched

across a big chunk of a 1080p display, unlike those titles which tried to

make excessive use of every pixel and now look extremely blurry and painful. This is the first time when

Space Quest achieved a certain

degree of graphic monumentality — the desolate vistas of Phleebhut, the

purple-dune planet, and Ortega, the richly-red-lava planet, are particularly impressive

and vital in creating a general feel of awe; while I may certainly be

mistaken by not taking into consideration the many arcade games of the era, I

think this might have been the very first time in the history of plot-based

video games that computer graphics really showed their potential to compete

with sci-fi movies in a vivid portrayal of the vastness, beauty and

(sometimes) terror of the outer space — the first yellow brick in the road

that leads straight to Mass Effect. The game introduced proper

cut scenes, occasionally providing skilfully done close-ups of characters

(this is the first time we get to really ogle our precious Roger) and nice

animations — that change of look on Fester Blatz’s face when you show him the

glowing gem is beyond priceless. Even the arrogant grin on Elmo Pug’s mug

when he is taunting you before the robot battle is generated with enough

skill to make you really hate the sucker’s guts back in the day. And although

they would obviously improve on this particular art in later games, each and

every one of the bizarre life forms queuing up for their Happy Meal within

the confined space of Monolith Burger is well worth examining, particularly

the «Employee Of The Week» whose face looks like it has been seriously

infested by the Bagpipe Virus.

|

||||||

|

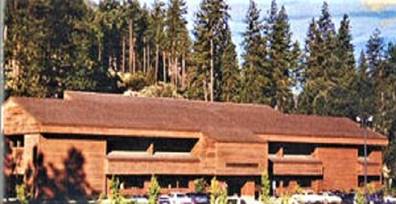

Sound Deciding that their

renovation of Space Quest for the

new age of computing should show no inferiority whatsoever to King’s Quest, the Two Guys also got

hold of a professional composer — who somehow turned out to be no less than Bob

Siebenberg, the drummer for Supertramp. Actually, the main reason was that

Siebenberg happened to live in Oakhurst and was looking for some extra

musical jobs in between touring; he had never had any prior experience

working with computers, but the fresh excitement of the enterprise helped

generate some magic, and come up with a full soundtrack which is, indeed,

probably the second best soundtrack from Sierra’s second generation — after King’s Quest IV, of course. But where the King’s Quest IV soundtrack was understandably folk-and-Renaissance-based,

with MIDI flutes, lutes, and harps creating a suitable fairy-tale atmosphere,

the music of Space Quest III,

which also accompanies you for most of the game, is suitably electronic,

cold, and sonically distant. Thus, the "Garbage Freighter" theme

sounds like a beginner robot composer’s take on a slow funky dance, with a

subtle hint of constant unseen menace running through its bass pulses; the

Ortega theme is a grumbling, creaky, sluggish industrial-ambient composition,

with its mix of moody electronic hum and booming metal gear sounding not

unlike something off David Bowie’s Berlin Trilogy; and the corridors of

ScumSoft are «enlivened» with spooky bass taps, scattered percussion bursts,

and occasional nonchalant whistlings of a couple bars from Roger’s theme to

get a combination of suspense and relief at the same time. The lighter moments in the game get

plenty of musical support, too — for instance, pushing forward through the

deadly pink dunes of Phleebhut is accompanied only by the sounds of gushing

winds, but as soon as you get to the safe haven of Fester’s World O’ Wonders,

a hilarious carnival theme begins playing, urging you to finally drop your

guard and relax. The easy-listening muzak of Monolith Burger quickly turns

out to be an elevator version of Roger’s own theme — and, of course, who

could ever forget the theme of Astro Chicken, which is essentially just one

bar of an old country theme looped for eternity... or at least until you

finally land all the bloody chickens? As a minor added bonus, Space Quest III features the first

ever spoken line in a Sierra game —

in the introduction scene, when Roger awakens in his pod and utters a single

"Where am I?" (Something I never got to experience until having

replayed the entire game thirty years later — because I, of course, played

the PC DOS version, and the digitized vocal audio was only working on Tandys,

Amigas, and Macs). This is, of course, little more than just a slight bit of

trivia — regular voiceover work would not start until more than a year later,

with Sierra’s third generation of games — but somehow in retrospect it still

adds a bit of gravity to the proceedings. And while I might be just imagining

things, it seems as if there is definitely something special to these early

full soundtracks — after they had become the normal state of affairs for

video games, they usually ceased to draw that much attention to themselves,

but back in 1988-89, it was very much about the challenge, with people really going all the way to prove that

digital music in video games can make all the difference there is, with King’s Quest IV and Space Quest III as the strongest

evidence for that. |

||||||

|

Like

all Sierra games of its generation, Space

Quest III runs in Sierra’s Creative Interpreter, which means a cooler

font than before and the ability to pause the game while typing commands into

the parser.

The parser itself is relatively well designed (no silly bugs such as were

present in Larry II, for

instance), and allows for a limited amount of experimentation, usually on the

humorous side (e.g. if you type in "look

at girl" while staring at the Monolith Burger employee, you get this

response: "The clerk is offended

that you would think he’s a female. Any idiot should be able to tell the

difference"). Action sequences are pretty

minimalistic — control your Astro Chicken with arrow keys, punch and block

punches with your robot during the Nuk’em Duk’em sequence with Elmo, track

and shoot down fighter ships on your control hud, nothing special or particularly

difficult / frustrating about any of that. Some agility is required while

navigating the tricky paths of Ortega, and there is a somewhat boring, if

altogether funny, sequence in the ScumSoft offices where, so as not to

attract attention to yourself, you have to empty («vaporize») the garbage

basket of every employee on your way to Elmo’s office — this one can get a

bit tricky if you miss a few pixels when correctly positioning Roger, but

nothing to lose sleep about. The overhead menu is

typical SCI, minimalistic and pragmatic; extra features include «VaporCalc»,

a non-functioning abacus intended to make fun of the calculator function

included in just about every piece of software at the time, and, of course,

the «Boss Key» which, this time around, really puts you sulking in the

corner. In other words, just don’t bother snooping around the menu and get on

with playing the game — a principle that would be somewhat violated in

subsequent installments, with their extra icons and stuff, but here it works

just fine. |

||||||

|

Although in many retrospective ratings it is Space Quest IV, not III,

which is typically extolled as the pinnacle of the series, I think it mainly

has to do with the technical excellence of that game — better graphics and

addition voice acting, including Gary Owens’ fabulous narration, would be

objective improvements that cannot be neglected. However, the disadvantage of

all later Space Quest games would

be that they were comfortably set in an already well established formula,

with running gags and self-referential jokes that could get stale and

annoying. In this game, on the

other hand, nothing as of yet is set in stone, and, in particular, Roger

Wilco is still more of an ingenious space traveler than the parodic space

loser he would become in the next three games (in a very similar manner to

Larry Laffer, whose portrayal in 1988-89 was also distinctly different from

later games along the very same lines). This implies a delicate and efficient

balance between humor, action, and suspense which would be seriously skewed

towards humor (and not always genuinely funny humor) in later games. Other

than technical antiquity (which, come to think of it, is not a problem now

that all Sierra games look like

museum pieces), the only common criticisms of Space Quest III which I am aware of is the late-plot-arrival (not

so much of a problem, in my opinion, as an interesting and rare artistic

feature) and the fact that the game is short — indeed, a complete playthrough

exploring every nook and cranny barely covers two hours of gameplay, but the

curious thing is that, due to the many different locations covered in the

game, it does not feel particularly

short: in fact, upon completion there is a distinct feeling that you have

just emerged from a fairly lengthy Odyssey. You found your way out of a giant

garbage freighter, you defeated a terrifying killer machine on a desert

planet, you accepted a rescue mission at a fast food joint, you caused a

volcanic eruption on the hottest planet in the universe, you infiltrated the

underground lair of the galaxy’s vilest software pirate company, you survived

a robotic battle in the arena, you emerged victorious from a major battle in

the skies, and you even helped your own creators get employment at Sierra

On-Line — just how long does a game

like this need to be? In

all seriousness, I could never find any major flaws with this game; to me, it

is as close to utmost perfection as an adventure game can get. The length,

the diversity of settings, the action, the humor, the satire, the suspense,

the beauty of the graphics and the music, all in just the right proportions —

a textbook example of how to make an adventure game into a piece of art, even

at a stage when you do not yet have the blessing of properly advanced

technology to go along with your imagination and creativity. Incidentally, Space Quest III is the only game in

the series which, up to this day, has not received a complete remake, either

from Sierra itself or the independent fan community: there have been

occasional attempts and partial results (including a fairly awful-looking 3D

reimagination), but nothing that has ever been brought to completion — and

the reason, I think, is that the original game is just so well-rounded in all

of its aspects (and still looks and sounds so good today!), that people

instinctively cower before the challenge. If you ever want to try one of

those rusty old classics, yet remain unsure if you will be able to handle

EGA-era graphics instead of modern 3D, text boxes instead of voice acting,

and command parsers instead of controllers, Space Quest III is probably the very first title that would end

up on my recommendation list. |

||||||