|

|

||||||

|

Studio: |

Sierra

On-Line |

|||||

|

Designer(s): |

Marc

Crowe / Scott Murphy |

|||||

|

Part of series: |

Space

Quest |

|||||

|

Release: |

March 4, 1991 |

|||||

|

Main credits: |

Creative Director: Bill Davis Programming: Scott Murphy, Doug Oldfield Music: Mark Seibert, Ken Allen |

|||||

|

Useful links: |

Playthrough: Part 1 (65 mins.) |

Part 2 (65 mins.) |

Part 3 (60 mins.) |

|||

|

By all accounts, Space Quest IV was the game that

should have properly launched Roger Wilco into the future — the future, that

is, of the gaming industry, rewarding our favorite janitorial anti-hero with

all the benefits that had already been laid upon his more privileged royal

colleague, King Graham: improved, hand-painted, 256-color graphics, brand new

point-and-click interface, and, ultimately, a full speech pack, finally

letting Roger complete his dorky image by talking to players in an

appropriately dorky voice. And the game did all that,

for sure, but not without a certain layer of dark clouds on the horizon.

First, despite nobody being able to tell at the time, it would turn out to be

the very last game that could be strictly credited to the «Two Guys From

Andromeda», whose partnership, allegedly for reasons more technical than

personal, would soon be dissolved, as only Mark Crowe ended up working on Space Quest V and only Scott Murphy on

Space Quest VI (which would

actually be more of a Josh Mandel project anyway). This is not to imply that Mark and

Scott were actually getting bored with their franchise and their parodic

universe, but it might imply that life was taking its heavy toll on the

creators, and that original excitement was slowly giving way to predictable

and exhausting routine. Second, Space Quest IV is precisely the place where you realize that

Space Janitor Roger Wilco has finally begun to exist within the framework of

his own personal mythology. The game was chockful not just with references to

Roger’s past — the plotline makes very little sense if you have not played

the previous three entries — but even to his future, stretching the Space Quest universe to almost

ridiculous dimensions without taking the time to properly populate these

dimensions, like staking a multi-million acre land claim without even taking

the time to investigate what lies within (gold mines or saline deserts).

Although, from a technical perspective, the franchise had just as much to

gain as any other at the time, in terms of actual substantial content the Two

Guys had very little left to prove. All the basic ingredients of the Space Quest universe had been

distilled and combined over the previous three games, and now all that was

left to the authors was to go on playing by their own rules — something which

is, of course, inevitable for any fictional universe if you let it run long

enough, but which may or may not be felt too

bluntly, depending on the artist’s talent and professionalism. In purely formal terms, though, Space Quest IV was an overwhelming

success. The game sold well, as usual; was largely loved by critics; and even

in today’s retro-lists, is often listed as the single best game in the Space

Quest series and one of the finest Sierra games ever. To me, this

evaluation has always seemed inflated — I was definitely not a big fan of the

game when I first played it — but there is no denying, either, that there is

quite a bit to praise about the experience, and not just its technical aspects (at least one of which, the

point-and-click interface, is always a minus rather than a plus in my book,

but you know that already if you have read my thoughts on King’s Quest V). So let us take a more

detailed look at the game’s various aspects, and see just how proverbially

mixed that reaction can be. |

||||||

|

Content evaluation |

||||||

|

I have to admit that I

harbor a bit of a distaste for convoluted, anything-can-happen,

time-travel-based plots in general, so if you want a detailed retelling of

the sequence of events in Space Quest

IV, go consult Wikipedia or something like that. In a nutshell, though,

it goes like this: Roger Wilco’s old arch-nemesis, Sludge Vohaul,

mysteriously comes back to life and is about to tear Roger a new one, when a

tall dark stranger appears out of nowhere and saves Roger’s ass by opening a

rift and sending him into another dimension... the dimension of Space Quest XII, to be exact. What happens next — as in,

the actual «plot» — is of very little importance, as Roger gets time-shifted

from one Space Quest sub-universe

to another, and eventually manages to outperform Mr. Vohaul, as well as earn

himself a major surprise when the identity of the tall dark stranger is

finally disclosed. Just as it was in Space

Quest III, for quite a long time you simply wander around without a clear

understanding of your purpose in life; the problem is, it does not feel

particularly satisfactory even when you do

grasp that purpose. In the place of a coherent and sarcastic story about rescuing

a pair of hip programmers from a vile software company of space pirates, Space Quest IV offers you a series of

fun, but disconnected vignettes: «Roger Wilco Is The Last Man On Earth

Alive», «Roger Wilco Is Introduced To Third-Wave Feminism» (actually, looks

more like second-wave, but what can you expect from a couple of old-school

programmers?), «Roger Wilco Is Lost In The Supermarket», etc. Approximately

90% of the game is really spent on these vignettes; each time the game gets

back to its main plot, it is mostly moanin’ and groanin’ time. To add insult

to injury, the final «boss fight» with Vohaul is not even a proper parody of

a proper fight, but rather an incomprehensible and illogical mess whose

design was probably put off until the last day before shipping. In the end, Space Quest IV is the only game in the

series which, if you asked me what it was about, the most I could squeeze out

of myself even after having just replayed it would be, «uhh... about time

travel?» Because you, too, will probably be left behind with memories of

having just visited Space Quest XII:

Vohaul’s Revenge II and Space Quest

X: Latex Babes Of Estros rather than memories of what you actually did to get back to the regular

timeline. Oh, right: apparently there is some planetary-level catastrophe

that you somehow have to remedy by going back and forth through time, and

that catastrophe was caused by... a virus-laden copy of a Leisure Suit Larry game (whether that

had anything to do with Sludge Vohaul or not, I’m still not sure). Anyway, stripping away the

disappointing rubble of the game’s main plot, its events are genuinely

enjoyable only outside of the plot

— such as Roger’s meeting with the «Babes of Estros», a fairly hilarious (and

nasty) jab at overconfident feminism on the part of the Two Guys; Roger’s

re-visiting the planet of Kerona from Space

Quest I, just to contemplate the differences between two eras of computer

graphics; and, most importantly, Roger’s adventures at the shopping mall,

where the Two Guys’ sarcastic attitudes towards all sides of modern pop

culture — be it arcade gaming, clothing, fast food joints, or advertising — really

break through and threaten to drown you in waves of non-stop laughter. These

moments seriously raise the bar on the series’ comedic potential, though at

the expense of completely and thoroughly solidifying the principal character as

a boorish nincompoop rather than a smartass Janitor Ivan that he was in the

previous games. This is, indeed, the

breaking point where Space Quest

became way too self-conscious about itself and began, much too often, falling

back on the inside jokes and tropes of its own mythology rather than

continuously breaking new grounds in storytelling. Sooner or later, even if

Gary Owens does an overall great job as the ridiculously pompous narrator,

you are going to get tired of having Roger’s alleged incompetence and

retardation shoved in your face all the time — even as he keeps quite

cleverly solving one tricky puzzle after another. Where the first three

games, especially the third one, were able to keep up a nice balance between «heroic

action» and comedy, Space Quest IV

plunges way too quickly and way too deeply into the territory of pure farce.

A strong and complex plot could have helped — which is why Space Quest V would be somewhat of an

improvement — but apparently, this time around the laughs were deemed more

important, and the Two Guys simply did not have enough time for much else. |

||||||

|

One thing you definitely

will not remember Space Quest IV

for is the strength of its puzzles.

The game was made at the asscrack of dawn of Sierra’s point-and-click era,

when the interface had already been remade but its functionality and purposes

still remained somewhat unclear — which means that most of the puzzles just

involve grabbing object A and using it on object B, with your main challenges

defined as pixel-hunting for both objects. The game is about as difficult to

complete as digging the proper hint book out of a pile of other hint books, or having to

backtrack all the way to a shopping mall to buy a necessary ingredient (a

rather tedious segment by itself). You might be duped for a while by all the

extra icons, such as «Smell» and «Lick», into thinking the game offers many

more possibilities, but it soon turns out that all of these extra things are

there just for laughs — we shall get to that later. Three things are added to regular

object-based puzzle-solving, and all three are questionable. One is, of

course, the dreadful copy protection crap — each time you need to fly

somewhere in your time pod, you have to enter some bizarre symbols that you

can only look up in the game’s manual: I can understand doing this once, but

having to do it every time would be seriously annoying for all the honest

players (and a good incentive to download a pirated cracked copy, as I

confess to actually have done at the time). For some reason, this kind of

bullshit was really hot with Sierra at the time — Larry V used precisely the same scheme, and gave a good incentive

to software pirates all over the «uncivilized» world. The second thing is that a lot, and I

really mean it, a lot of your

actions are heavily dependent on perfect timing. Everywhere you go, you have

to avoid something, wait for something, or seize that one tiny window in time

that gets you what you need to accomplish and/or saves you from certain

death. This aspect became particularly frustrating with the appearance of

ever more powerful CPUs, since timed events in Sierra games were often

benchmarked against current CPUs rather than actual time — making the game

virtually unplayable in spots — but even upon release, all these timed events

must have seemed like a cheap copout from the actual challenge to design a

good puzzle. Finally, there are the actual arcade

sequences — for those of us who already hated the timed events, these must

have felt like an extra vicious slap in the face. Granted, they are all

optional; one even actively warns

you about itself and proposes to skip it ("not recommended for die-hard

adventure players, the arcade-squeamish, or those with poor to non-existent

motor skills" — yeah, thanks for rubbing this in my face, buddy!). But you

cannot boast the highest score possible if you do not play these arcades, and

you are still forced to go through those pangs of guilt and self-doubt if you

choose to skip them, right? Granted, they are at least somewhat original,

particularly the Monolith Burger mini-game where you have to flip as many

burgers as possible before the conveyer begins insanely speeding up; the other

game, «Ms. Astro Chicken», is a slightly more complicated variation on «Astro

Chicken» from Space Quest III and

is not really half-bad as an arcade diversion, but I’d still rather it were

just a minor side quest with no effect on the score, and certainly not at the

expense of proper adventure game

puzzles. In the end, if you strip away all the

game-breaking timed crap and all the arcade sequences, you are left with

virtually nothing to challenge your logical skills and adventurist intuition.

In this, Space Quest IV is not alone

among its Sierra contemporaries from the early point-and-click years — King’s Quest V and Larry V both suffer from the exact

same problem. Fortunately, at least Space

Quest IV is saved from being a complete disaster by that single important

factor which is intentionally missing in King’s

Quest V and accidentally missing in Larry

V — the humor. |

||||||

|

At least in terms of spirit, Space Quest IV works more often than

not. Despite spending the first big chunk of the game in a lonesome and

somber environment (the future ruins of Xenon), the game ends up as the most

populated Space Quest title up to

date — from the proud Latex Babes of Estros and all the way to that planet’s

lively supermarket, Roger can finally find plenty of people to interact with,

which, in turn, raises the game’s comedic potential significantly. In

addition, traveling by time pod gives you the ability to create your own

Instant Contrasts wherever you feel like it — you can skedaddle back and

forth between the lively shopping crowds on Estros and the desolate solitude

of Xenon at the blink of an eye (just keep your damn copyright protection

codes close at hand). Through most of the game, you are

actively hunted by the «Sequel Police», a mysterious special force which is

seemingly on Vohaul’s payroll — meaning a lot of tension and a general

directive not to tarry too long in one place. Xenon is never a safe zone, and

neither are the rocky crags of Estros; even the mall, at one point in the

game, becomes one large chase scene, though at most other times you can

stroll through it without too much fear (as long as you do not shoplift or

anything). This is nicely carried over from previous games, where being

stalked by various robotic enemies was also Roger’s favorite pastime, though

occasionally tension spills over into frustration, particularly if you run

into various timing issues (very easy to do both in Vohaul’s fortress on

Xenon and on the rocks of Estros). At the same time, the game is so much

skewed in the direction of humor that «tension» rarely ever stands a chance

of giving you the rightful jiffies, certainly not when you have Gary Owens

triumphantly narrating the viscerous details of each one of your deaths — and

most definitely not when you get around to the shopping mall, where getting

chased by the Sequel Police and dying in the process is just a natural part

of the life-as-a-joke cycle. The mall, with its endless lambasting of pop and

consumer culture, is the high point of the game, be it the sickeningly friendly

bot advertising «CDGIROMTV» or the «Cyber-Depunker» ("works while your

child sleeps to replace black market implants") at the local Radio

Shock, or Roger fiddling through a set of hilarious hintbooks for games like SimSim ("a simulated environment in

which you can create any simulated environment!") or King’s Quest XXXVIII: Quest For Disk Space

(where the joke is now on the Two Guys — who is going to laugh today at a

game "over 12 gigabytes in length"?). And few things are more

hilarious in video games than holding a conversation with a variety of burger

ingredients ("I smell like any other set of 299 year old buns! While I

have absolutely no taste, I do have a shelf life of three centuries"). For me, personally, the highest point

of the game was Roger getting bullied by the alien bikers in the bar on

Kerona — where everything could have gone smoothly were it not for the fact

that the planet remained in the CGA graphic resolution of Space Quest I, while Roger landed on

it in his full VGA 256-color glory, earning himself some serious burns from

the «boomer generation» ("Whatsamatter, monochrome not good enough for

you?"). The allegory of CGA vs. VGA symbolizing the nerd vs. jock

conflict just works so alluringly well, and something tells me that it would

no longer be possible to play on similar oppositions today (what are they

going to do, mock the 2K standard from a 4K-viewpoint? hardly imaginable). This rampant humor, which indeed

surpasses anything the Two Guys

tried out earlier — well, some of the jokes in Space Quest III are quite on the same level, but there simply

aren’t enough of them — is arguably the main reason why fans hold this game

in such high esteem. The fact that they have little, if anything, to do with

the storyline is irrelevant — as is the storyline itself, actually. What is

relevant is that at this point, the Space

Quest franchise has fully crystallized as a barrelhouse of laughs, making

its elements of action, suspense, and visual fantasy at best secondary to its

comedy. I can see where people might like that — why does one play Space Quest

if not for the jokes? — but I would still like to have seen the franchise be

able to retain the same balance as, say, Quest

For Glory had managed to preserve until the very end, with its clever-as-heck

mix of the serious and the comical. |

||||||

|

Technical features |

||||||

|

It goes without saying that

Space Quest IV benefited hugely

from the transition to 256-color VGA and painted images instead of fully

digital graphics. (There was also a downscaled EGA version for players with

antiquated hardware, but, like all such affairs, it looks downright

horrible). However, the fact that much of the game takes place in cramped

locations, and that the emphasis is consistently on humor rather than on

visuals, I doubt that it would ever end up on anyone’s list of «Top 10

Visually Stunning Sierra-On Line games». Of all the locations,

probably the most visually expressive are the ruins of Xenon in «Space Quest

XII». The lonesome desolation of the place, with huge abandoned drab concrete

structures and rubble contrasting sharply with the red-tinted atmosphere provides

feels that are not unlike the ones experienced in the previous games on

planets such as Phleebhut and Ortega, only this time emphasizing the man-made

nature of the desolation. The nature sights on Estros are also coolly

designed — there is a little maze of natural rocky corridors and stairways

that looks like something out of a whacky Sixties’ fantasy movie — but, alas,

they are there only for a few moments, and you do not really get to enjoy

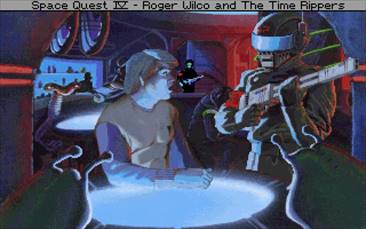

them much because of the Sequel Police running hot on your trail. Close-up cutscenes are

generally fine: the Latex Babes of Estros have been arduously shaped out with

the diligence worthy of a Leisure Suit

Larry artist, the pigboss manager of Monolith Burger is the evil grin of

capitalism staring you right in the face, and although the ugly bikers of

Kerona normally look like CGI sprites, their own personal close-up lets you

experience all the horror of having to face such a gang of thugs in an

intergalactic drinking environment. They are all, however, few and far

between. As for the animation, extra

resolution and early motion capture techniques have certainly helped Roger

Wilco (and his friends) become more human-like when you walk him across the

screen, but I do not necessarily see this as an improvement in retrospect:

most of those early 1990s Sierra sprites suffer from too many sharp angles

and too much blockiness — in a way, I prefer the «matchstick legs» of earlier

sprites just because they did not even begin to aspire to human likeliness.

Still, you gotta appreciate the effort that the animators put into fleshing

out Roger’s moves during the short segment in which he has to cross-dress —

those little bits when the guy has to keep his balance while moving around

the mall in high heels are priceless. |

||||||

|

With Bob Siebenberg no

longer in the picture, the musical soundtrack by Mark Seibert and Ken Allen

here is decidedly mediocre: not bad per se, but lacking the futuristic

mystery of Siebenberg’s ambient compositions and more clearly oriented at the

decisive interpretation of Space Quest

as «comedy». Only the

basic theme of the post-apocalyptic Xenon is emotionally intense and

impressive on its own — cold, gruff ice plateaus of synth tones overlaid upon

grim, martial-sounding synth bass and conveying an impression of death and

devastation at your feet and danger

around the corner at the same time. But the musical themes accompanying

lighter and funnier places — the mall, most importantly — are not much to

write home about, except those that are already recycled from the previous

game, such as the Monolith Burger and the Astro Chicken themes. Much more important, of course, is the

fact that in December 1992, Space Quest

IV became the first ever Space

Quest to be fully voiced — mostly by Sierra’s own employees or

little-known names in the voice actor industry, but with one very important

addition: radio host Gary Owens as Narrator. Gary might be the single most important reason

behind the fans’ adulation, since his usual deadpan-nonsense style serves him

so well in a Space Quest setting.

You most certainly have heard nothing until you have heard Gary declare

"It’s against the Third Law of Mall Security to be caught licking mall

components!" or "Take it from someone who knows sick: licking

corpses is going way beond simple dementia!" And the good news is that

he has approximately 90% of the game’s lines — Roger himself speaks only in

the rarest of situations, and most of the other characters are restricted to,

at best, one or two scenes. (Interestingly enough, Scott Murphy himself

voices Sludge Vohaul, but since the vocals are electronically encoded for

Terrifying Effect, you do not really get a whole lot of personality from the

experience). That said, as great as Gary’s

contribution to the game is, he is also one of the biggest reasons why the

entire game feels like one big vaudeville show — when that ridiculously

arch-pompous intonation crops up even in the most terrifying places (Xenon),

nothing de-terrifies the experience better than yet another Gary Owens bomb.

I am very happy to see the man’s voice talent preserved in such a form in

this game — but I am also very happy that Space

Quest III came out before the digital speech era, and before the Two Guys felt like every single line in the game

needed a comedic flair to it, rather than just a certain percentage of them. |

||||||

|

Interface As

one of the first Sierra games with the brand new point-and-click interface, Space

Quest IV shares all the benefits and disadvantages of King’s Quest V. The text parser is gone

for good, but in your actions you are essentially limited to three operations

— «look», «talk», «take / use» something, with fairly generic responses for

the latter two when applied to the majority of objects. Perhaps somewhat

dissatisfied with the crude limitations of such an interface, the Two Guys

got a wee bit more creative than Roberta Williams and added two more icons —

«Smell» (a nose) and «Taste» (a tongue). Unfortunately, they are there mostly

for the laughs, never serving any important purpose — again, giving a boring

generic response when applied to most objects, but occasionally quite amusing

indeed (don’t forget to smell and taste all the burger ingredients, for instance).

Still, their addition feels more like an early parody of the point-and-click

ideology than an attempt to intellectualize the interface, if you know what I

mean. Other than «Smell» and

«Taste», however, there is nothing out of ordinary about the interface (no

boss key, no special options other than the usual save / restore / quit,

etc.). The gameplay is almost fully predictable, too, with the exception of

the already mentioned arcade sequences — of which Ms. Astro Chicken is the

actually smoothly functioning one, well programmed for anybody with a soft

spot for archaic arcade games. (The Monolith Burger sequence, though, is only

good for all the laughs from talking with Ketchup and Mustard). Do watch out,

however, for timing-related bugs — the escape from the Sequel Police in the

mall can, in particularly, be a really tough challenge even for those who

have properly configured their DOSBox for playing in the modern age. Shame on

you, Two Guys, for spending so much time thinking on the future of Space Quest and not so much on the

future of computer processing power! |

||||||

|

A brief survey shows that people usually have fond memories of Space Quest IV and tepid memories of Space Quest VI, despite the two games

having much in common (the presence of Gary Owens, for one thing): the

defended point of view here is that IV

was funny and fresh, while VI truly

passed the point of self-parody. Personally, though, I think that VI simply took all the flaws that were

already present in IV and amplified

them — but then at least VI had

something resembling a coherent plot, whereas IV was there largely for the laughs. (Not to mention I’d much

rather play Stooge Fighter any time

of day than Ms. Astro Chicken!) Anyway,

in the end I still like the game —

enough to heartily recommend it to anybody, young or old, who hasn’t played

it yet. Its good points — the humor, the sarcasm, the occasional wittiness,

the pervasive Gary Owens — outweigh the bad points or, at least, render them

forgivable. However, along with Leisure

Suit Larry, Space Quest IV is

one of the two strongest arguments that the Founding Fathers of Sierra

On-Line had really lived through their Golden Age in the second half of the

Eighties. While there would still be fresh blood, most notably Lori Cole and

Jane Jensen, who understood how to bring adventure games properly up to the

standards of a new decade, the old blood, like the Two Guys and Al Lowe (and

Roberta Williams, for that matter), found itself too heavily weighted down by

its glorious legacy and coasting on its achievements. Curiously

(running a bit ahead), while Space

Quest IV and VI would indeed be

quite similar in tone and atmosphere, the fifth game in the series would be

significantly different — and unquestionably superior to both of these even

while completely lacking voice acting. The reason? The fifth game was far

more focused on the plot (a genuine

StarTrek-ish adventure) than on the humorous mini-vignettes that constitute

the majority of both of those other games. With that much invested in the

story, there was less time to be spent on silly inside jokes and the

ever-annoying deprecation of Roger Wilco’s character (though there would

still be plenty of humor). In a way, Space

Quest V would feel more like the proper sequel to Space Quest III to me than its predecessor — proving that the

cruel course of history is not really irreversible as long as there is the

proper will to reverse it. |

||||||