|

|

||||

|

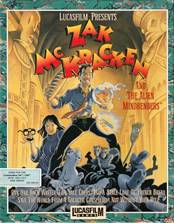

Studio: |

LucasArts |

|||

|

Designer(s): |

David

Fox |

|||

|

Part of series: |

—— |

|||

|

Release: |

October 1988 (DOS) / 1990 (FM Towns) |

|||

|

Main credits: |

Programmers: David Fox, Matthew Alan Kane Music / Sound Effects: Matthew Alan Kane |

|||

|

Useful links: |

Complete

playthrough (180 mins.) |

|||

|

To

paraphrase The Smiths, "some games

are bigger than others, some games’

fathers are bigger than other games’ fathers". Although David Fox, a

general computer and multimedia wiz who was one of the founding fathers of

Lucasfilm’s Game Division, was quite a key figure in the history of

LucasArts’ rise to prominence — it was he who designed and did most of the

work on Labyrinth, the studio’s

first and, some might argue, the most innovative and revolutionary

contribution to the art of the adventure game — the average gamer these days

is much less probable to run into any mention of his name than those of Ron

Gilbert, Dave Grossman, or Tim Schafer (even if, in recent years, he has

actually made a comeback into that world and rejoined Gilbert and Grossman on

such projects as Thimbleweed Park

and Return To Monkey Island). This

is not only due to Fox quitting the studio at an early stage, before it hit

its major artistic stride in the early 1990s, but also to the fact that his

second and last game for the studio, Zak

McKracken And The Alien Mindbenders, failed to live up to the high

expectations set by 1988’s Maniac

Mansion — or, at least, that’s how it largely seemed to critics and customers at the time. It is a rather

classic example of «the one that had to fall through the cracks» because something is always bound to fall

through the cracks, no matter how unjust it might seem to those willing to

lower themselves upon the floor and carefully re-extract it with nostalgic

pincers. Granted,

in the immediate aftermath of the technical and stylistic breakthroughs

introduced by Maniac Mansion it

would be difficult to expect an equally warm reception to a sequel (well,

technically it was a completely different story, but in spirit it might as

well have been dubbed a sequel) that, upon first sight, merely repeated the

formula of its predecessor, perhaps with a slightly expansive and more

ambitious approach that could, for the average player, feel more frustrating

than inspiring. Pretty soon, games like Loom

and the Indiana Jones series would

once again push that wagon forward, but Zak

McKracken, if you ever decide to play all LucasArts games in

chronological order, does give a bit of that «coasting» feeling — never a

good thing in the age of true progress, which is precisely what it was for

adventure games in the late Eighties. And

yet, in some ways Zak McKracken did

significantly differ from its surroundings, even if this rather becomes

clearer in retrospect. For one thing, of all the snarky tricksters and

miscreants in LucasArts, David Fox seems to have been (along with Brian

Moriarty of Loom fame) the most

serious of the lot. Unlike Gilbert and Grossman, whose chief interests, so it

seems, were in digital gaming from the very beginning, Fox was more of a

general computer expert, having written books such as Computer Animation Primer and Armchair

BASIC, and even opened (in 1977) what Wikipedia claims to have been «the

world’s first public-access microcomputer center». Later, after quitting

LucasArts, he would go on to design educational software rather than

straightahead computer games (that is, until he got back with his old pals

from the studio decades later). And it is said that his original design for Zak McKracken was a game that took

itself seriously — until Gilbert talked him out of the idea, for whatever

reason (perhaps he simply did not believe that the time was right for the

barely self-conscious art of video gaming to get serious, or was afraid that

Fox would turn the studio into a clone of Sierra On-Line). Even

so, despite Zak McKracken And The Alien

Mindbenders ultimately becoming yet another hilariously absurdist

creation cast in the image of Maniac

Mansion, the game still explored relatively serious topics; where Maniac Mansion was simply a

straightforward goof-off (at best — a smart parody of family-oriented horror,

sci-fi, and generic cartoons rolled in one), the main subject of Zak McKracken — that of the influence

of tabloid tripe on public conscience — had a certain modicum of social

relevance, not easy to properly assess unless you actually gave it some

thought, but if you did give it

some thought, you might even have made a case for Zak McKracken being a true «thinking man’s game» at a time when

even the most sophisticated adventure games were still essentially

re-enactments of fairy tale clichés or straight-up parodies of pop

culture. The problem is, back then people rarely evaluated games for their

actual content; immersion, user-friendliness, the overall quality of the

puzzles and, of course,

improvements in graphics and sound were so much more the rage — and on all

those counts, Zak McKracken did

well enough to earn a passable grade from the critics, but not enough to earn

their genuine admiration. In other words, the game’s flaws were more easy to

savor than its virtues. Nevertheless,

a small, but dedicated cult following did stabilize around the game,

protecting it from going down in history as a disaster and even producing a

couple of amateurish, indie-made sequels, for lack of an official one

(understandably, after Fox left the studio, nobody ever cared about

resurrecting Zak McKracken the same way the studio cared about resurrecting,

say, Guybrush Threepwood). The typical retro-verdict that I see these days

around the Web is along the lines of «well, it’s a pretty hard game, but if

you can get around its mercilessness to new players, it’s a fun enough romp

with some educational value to it». Which may be good enough for obsessed

retro-gamers and absolutely condemning for everybody else — but even if you

have never played Zak McKracken and

never intend to play Zak McKracken,

this does not necessarily mean you won’t get anything out of reading about Zak McKracken. So here we go! |

||||

|

Content evaluation |

||||

|

Plotline On the surface, the basic plot of Zak McKracken all but mirrors the story of Maniac Mansion — just like in that game, here we deal with a

supernatural alien intrusion, the ultimate goal of which is to achieve world

domination through indoctrination of the victims. However, in Maniac Mansion that aspect was not

particularly well thought through, and the entire line of the Evil Meteor

possessing Dr. Fred, the Mad Scientist, was merely a plot-serving goof

without any implications. The game’s story was just an (admittedly funny)

parody on the battle of Absolute Good vs. Absolute Evil, and all that mattered

about it were the isolated scattered jokes, gags, and (of course) puzzles. Fox

took his duties more seriously. First of all, as an early pioneer of

«edutainment» software, he made sure that the game would be far more

expansive than its predecessor. As a journalist working for The National Inquisitor, a tabloid of

poor reputation but rich circulation, Zak McKracken will have to travel all

over the world — from San Francisco to London, from Egypt to Mexico, from

Kinshasa to Tibet; he will have a chance to get lost in The Bermuda Triangle

and even grace the planet of Mars with his appearance. Although all of these

locations are represented in facetious, «tabloid-style» mode, Fox had clearly

done his research on everything associated with paranormal activity — the

Pyramids of Egypt and Mexico, Stonehenge, witch doctors, shamans, pretty much

everything and everyone that has ever attracted the attention of

sensation-seekers, and his tale unwinds in a fun world mixing cultural

authenticity with tabloid fantasy. The influence of Broderbund’s Where In The World Is Carmen Sandiego?

is undeniable, though Zak McKracken

is not really here to test your knowledge of geography: its chief focus is

exploration of popular cultural mythology rather than historical trivia. Second,

the game’s main plotline is, in a rather sly (and, for that period, extremely intelligent) manner,

somewhat metaphorical of the general human condition. According to the

story, the evil alien race of «Caponians», having taken over the intercommunication

monopoly of «The Phone Company», are launching a plan to subjugate humanity

by constantly transmitting a special «Mind Bending» signal, designed to

lower the intelligence level of everybody subjected to it. It is up to Zak

and his friends, freelancer Annie Larris (possibly named after David’s spouse

and work partner, Annie Fox) and two Yale students, Melissa and Leslie, on a

spring break vacation to Mars, to set things right by getting in contact with

the other alien race («The Skolarians») and gathering enough clues to

construct a super-device that will neutralize the harmful effect of «Mind

Bending» and ruin the evil guys’ plans. The

irony here is, at the least, two-fold. On one hand, the «Caponians» are a

good excuse to poke some well-protected fun at the overall sad state of

affairs in the field of human intelligence. At the very start of the game, if

you make Zak sit through a TV report of what’s going on, you get quite an edgy warning of "If you’ve been feeling increasingly stupid

lately, you’re not alone!" — which is somehow even more comforting

to hear today than it was back in 1988. On the other hand, the plight of Zak,

a disillusioned truth-seeker just aching to break out of the vicious circle

of sensationalist tabloid fantasies, ultimately leads him to realize that it

is only by fully and relentlessly embracing such fantasies that humanity can

be saved in the first place. In other words, fire must be fought with fire:

only the most fantastic and stupid strategies of action can help eliminate stupidity

and get the world back on track. This

is, in all honesty, such a fabulous concept that I only wish it could have

been better realized at a latter age; unlike Maniac Mansion, which, I believe, is fine just as it is, Zak McKracken is literally screaming to be remade with a bigger

budget, more detailed script, sharper and less laconic dialog, and fuller

character depictions. As it is, plot- and moral-wise the game is but a tasty

shadow of what it could really have been even in the soon-to-come age of Day Of The Tentacle, let alone today.

The entire story, including all the cutscenes, can be condensed into about

half an hour; the rest of the playtime will be occupied by your trying to

crack its puzzles and navigate its endless mazes. It’s got enough time to

poke fun at news of two-headed squirrels, golf-loving gurus, diplomated witch

doctors, Martian aliens, and, of course, The King (what’s a good game without

at least one Elvis joke?), but it does all that in a pretty telegraphic

style, which undermines its satire. As

with Maniac Mansion, one could

argue that the game’s pithiness is a source of charm in itself — if hilarious

absurdity is the name of the game, why spoil it by adding unnecessary detail

or, even worse, by attempts at expanded logical explanations of what is going

on? The only problem with that is that Maniac

Mansion had a perfect amibition-to-realization ratio: all the action took

place inside one single location, with a fixed minimal number of characters

whose goals and personalities could easily be established with just a handful

of cutscenes and dialogs. Zak McKracken

goes on an ambitious sprawl instead, taking you from one location to another

without bothering to seriously invest into any of the places or people. Even

the educational content is fairly limited — beyond learning the names of

cities such as Katmandu or Kinshasa, or seizing the overall difference in

visual style between Egypt and Mexico, you don’t really get to enrich your

knowledge, and, in fact, the game would hardly be recommendable for kids, not

just because it is too difficult or too laconic, but also because it

deliberately messes up fact and fantasy, which is hardly a great educational

strategy. (Years later, Sierra’s authors would come up with a good way to

separate one from the other while designing Pepper’s Adventures In Time, but that would already be a whole other

age). That the plot does not follow any clearly defined

logical strategy is probably not a valid accusation for the game, whose

absurdist nature calls for absurdist moves on the part of the protagonist —

in order to find all the missing pieces for their magic artifact, Zak and

Annie have to blindly grope around several different corners of the world

(which can be quite a financial strain on your limited resources), just as

often relying on their intuition as their counter-intuition. Sometimes,

however, it does go wildly over the top, when Elvis (or, at least, a pretty

darn good resemblance) is revealed as the leader of the Caponians, or when

the spiritual link between the Holy Men of Nepal and the Congo takes on the

form of a golf club; these ideas, naughtily sarcastic as they are on their

own, probably fried the brains of many a game reviewer, eventually hurting

sales and ensuring the game’s future status of «cult favorite». In the end, though, almost every element of the plot

makes sense: Zak McKracken is a

brilliantly well thought-out post-modern fable on the average person’s mix of

cultural stereotypes and superstitious (I wanted to write ‘religious’, but corrected

myself before it was too late) beliefs. And it’s well worth playing just to

get to that bit at the end: "CONGRATULATIONS!

YOU HAVE SAVED THE WORLD FROM STUPIDITY!", followed by "The people of Earth rapidly regained their

former level of intelligence... and traded in good karma for the latest food

fad: two-headed squirrel burgers!" Somehow, more than 30 years since

the release of the original game, there is still some sort of bitter

prophetic ring to those lines. Perhaps we are still waiting for a real-life

Zak McKracken to save the world from stupidity, so that we could all go back

to our two-headed squirrel burgers instead of having to take in all that

crazy shit the modern world keeps throwing at us, eh? |

||||

|

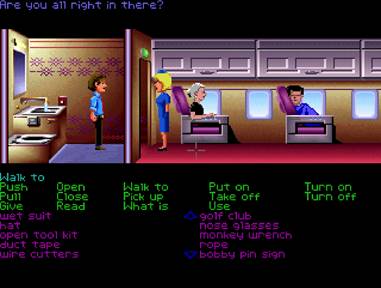

Puzzles On the puzzling front, Zak

McKracken has very few differences from Maniac Mansion: it uses the same interface of about a dozen

different verbs, most of them combinable with a variety of complements =

objects that Zak can pick up during his travels, and most of your time will

be spent trying out the various combinations — sometimes randomly, because

this is a batshit-crazy LucasArts game that typically requires batshit-crazy

LucasArts-style logic to get by. If you’re one of those «oh I hate adventure

games because they offer insane, logic-defying puzzles» kind of guy, Zak McKracken is definitely not the game to try and change your

state of mind. One thing that makes Zak

a definitely more difficult, and at times frustrating, experience compared to

Maniac Mansion, is its sprawling

nature. The Mansion was pretty big, but it was still a single location with

all of its floors, corridors, and rooms combined. If you wanted, you could

divide it into three chunks and set each of your playable characters to watch

over one of them, which made things clean and efficient; a couple of playing

hours later, you’d have the overall layout of the whole thing nicely settled

in your head and it would be easy to work out which elements and objects in

which part of the house relate to each other (or not). By contrast, the

universe of Zak is quite gigantic,

consisting of multiple disparate locations that can only be reached by taking

plane rides that (a) take small, but valuable chunks of your time and (b)

even worse, cost quite a bit of money that you can run out of. Forget to

obtain a useful item in San Francisco (like, for instance, a pack of bread

crumbs!), travel to Lima and watch yourself get fucked as you are hopelessly

stuck on your mission and don’t

have a single penny left in your pocket to travel back home and pick up the

required thingamajig. Indeed, Zak McKracken

is not only one of those very, very few LucasArts games that can be brought

to a halt by the player dying — any

of the four playable characters can get into a small handful of situations

where they expire and the game needs to be restarted or restored — but also

by the player getting stuck in an unwinnable situation, something that

contemporary Sierra games were frequently accused for. To move around, Zak

and Annie need money, and while there are

ways to replenish your credit card, they come relatively late in the game;

besides, it is theoretically possible to get stuck in some remote location

without the means of purchasing your next ticket or to make a quick buck anywhere in the vicinity. Additionally,

while trying out different solutions, you can lose important objects that are

necessary to complete vital quests — or, at one point, Zak can get stuck in a

jail cell in Katmandu without any ways of getting out (Annie can help, but

only if she has the financial means to get to Nepal and a necessary implement to call the shuttle to the airport from

her San Francisco apartment). All of this goes so blatantly against the established LucasArts

strategies of pleasing the player that I can only explain it by the

chronological factor: back in 1988, the laws set out by Ron Gilbert were in

the early stage of application and did not require being fully shared by all

the other designers. The (relative) underperformance of the game, compared to

Maniac Mansion, probably convinced

everybody that the Gilbert way of doing things was the way to go, and no other LucasArts game after Zak McKracken would dare inconvenience

the player in any such manner. That said, taking good care of your save files

and keeping a sharp eye on the state of your bank account is not that hard to

do, that is, once you figure out that you actually need to do it: with most of the classic LucasArts games luring

you into relaxing, it’s easy to forget that a few of the early ones do demand

that you keep your guard up. A bigger problem than getting stuck because of doing something

wrong might be getting stuck because of not knowing what to do. After you

have properly explored San Francisco and met up with Annie to learn of the

impending catastrophe and the one possible solution to prevent it, you are

essentially placed in free-roam mode — and the game is pretty harsh on you

when it comes to getting actual clues on where to go next, instead of blindly

groping around the world in classic «go-I-know-not-

whither-and-fetch-I-know-not-what» fashion. You do get some clues — which, every once in a while, require a bit

of outside knowledge; for instance, connecting the dots on a cave painting

reveals the image of an ankh, which logically suggests that your further

adventures will have something to do with Egypt, provided you know what an

ankh is (and even if you don’t, neither the game itself nor the accompanying

manual will ever insult your intelligence by offering an explanation). But it

is more likely that most players will just keep on randomly putting Zak on a

plane to whatever location, only to discover, half an hour later, that you

are not in possession of that one

particular important object you need to crack that location’s task and have

meaninglessly wasted your money on two plane tickets (or more, as some

destinations can only be reached through a connecting flight). Adding to the number of frustrating bits about the game’s design

is its accursed system of mazes

(ugh!). Mazes will be waiting for you everywhere — in the African and South

American jungles, inside the Egyptian pyramids, and even inside the Martian

ruins. Now in most adventure games, mazes are merely the cheap equivalent of

a proper puzzle when developers run out of budget for designing something

more creative, tasking the player with finding an additional piece of paper

and pencil for several minutes of brainless tedium — but Zak McKracken actually does it worse by mixing a few real,

fixed-design mazes with «pseudo-mazes», a set of randomly generated images

where you should not memorize any paths, but rather just allow your character

to wander and blunder until he randomly falls upon the blessed clearing.

Since the game never warns you about which of the two maze types you are

about to encounter, you may end up writing out maps for one-time only ghostly

apparitions, and not writing out

maps where you really need them. Honestly, while not particularly tragic, the

maze system in Zak McKracken is

simply one of the most stupid and annoying bits of design in the entire

history of LucasArts. The actual inventory-based puzzles, by comparison, are

relatively simple; nothing stands out as particularly challenging or, for

that matter, particularly memorable. Some of the challenges have alternate

solutions, or (sometimes) can be performed by different characters with

slightly different results. Some objects can be used differently; for

instance, you can make regular use of the knife you find or you can bend it

out of shape, eventually allowing you to make a profit and get an extra joke on the subject of modern art as well. Some

puzzles require cooperation, similar to the tactics employed in Maniac Mansion (e.g. one character has

to hold down a lever while the other goes through a door, etc.). All in all,

not a lot to write about. The main challenge of the game is to really

familiarize yourself with the scope of its universe — oh, and to watch out

for those precious hotspots, of course (arguably the easiest way to get stuck

is to miss some tiny pixelated area on the screen that contains the proper

object to interact with). |

||||

|

It may be a bit random, but remembering that the game came out

in 1988, I can’t help but be reminded of yet another title from the same year

where you had to deal with a protagonist pulled out of the relative chic and

comfort of West Coast civilization and plunged into a world of exciting,

dangerous, and bewildering adventure — Sierra’s Leisure Suit Larry Goes Looking For Love, with the game’s first act taking

place in Los Angeles rather than San Francisco. The contrast, held up by the

plot, the graphics, and the suspense, was quite striking — and at the same

time, the game humorously played on all the similarities between life in L.A.

and life on the tropical islands of the Pacific, poking intelligent fun at

globalization and commercialization (which most players and critics probably

missed in their avid hunt for smut, smut, and more smut). In

some ways, Zak McKracken does the

same, as Zak discovers the influence of the modern world on many of the

locations he visits — from the African witch doctor’s diploma from «Watsamatta University, Master of Cranial

Diminishment» to the interiors of «The Friendly Hostel» all the way up on

Mars. However, on the whole the game remains stuck in the same kind of zany

parallel reality as most of the classic LucasArts titles, and its style is

more reminiscent of a comic book than a comedy movie. Dialog throughout the

game is sparse, terse, and minimal (as compared, for instance, to Al Lowe’s

totally unstoppable verbosity — often brilliant, but sometimes verging on obsessively

annoying), and its attention to detail is... well, let’s say, sporadic: every

once in a while, there is something random out there just for the sake of

humor, but it feels tacked on just so there’d be at least something of the «world-building»

variety and not directly and strictly related to the plot. As in Maniac Mansion, there’s a suspicion of

the game designers still being stuck way too much in the «text adventure

game» mode, where the very nature of the game prohibited the writers from

piling up too much detail. (One

good illustrative example: in both Zak

McKracken and Larry II, players

find themselves aboard a plane with a rude and obnoxious stewardess

explaining flight rules. Dialog from Zak:

"If we lose cabin pressure, oxygen

masks should appear. But don’t count on it." Dialog from Larry: "Oh, and if during our flight those cute little yellow masks happen to

drop down from their overhead compartments... why, just ignore them. Lately,

those practical jokers in maintenance have been substituting nitrous oxide

for the oxygen again!" Feel the difference in style? To be fair,

though, the humor level in both these takes is quite comparable, so the

less-is-more principle applies fairly well to Zak McKracken on occasion). Even

so, Zak McKracken is still a unique

experience in its own way. There was always something disarmingly charming

about Maniac Mansion’s minimalism,

which, of course, stemmed not from any kind of intentional designer

philosophy, but from the limitations of its age — small budget, tiny staff,

rudimentary technologies, first experience — and for all the innumerable ways

in which Day Of The Tentacle would

have it beat five years later, it would do so at the inevitable expense of

that laconicity. Zak McKracken,

however, arrived just in time to recapture that atmosphere and apply it to

the world at large, rather than spend it all on one particular location. Now

you have Zak arrive in Peru and find an «Ancient

Incan Bird Feeder: Fill Only With Dry Bread Crumbs», because why the hell

not? Besides, some people might actually get tired of drowning in waves upon

waves of LucasArts’ patented humor in later games — Zak McKracken, by using it sparingly, comes across as more of a

real puzzler than an excuse to crack off as many jokes as possible,

regardless of quality (yeah I’m lookin’ at you Curse Of Monkey Island!) Finally,

as in Maniac Mansion, there is a

bit of tension and suspense here — after Zak receives the ability to transmogrify

into the spirits of birds and animals, the Caponians begin to sense his

presence and you have to remember to quickly clear out of recently visited

locations to prevent yourself from being captured. Capture never leads to

death (just a temporary round of brainwashing that eventually results in Zak

getting back to normal), but it still delays your progress, so getting

captured is never a good thing (actually, it’s worse than what it was in Maniac Mansion, where getting thrown

into the dungeon only meant that you had to activate another member of the

party to get you out — here, you get automatically transported back to San

Francisco, meaning you will probably need to spend a large wad of money on

your next airplane ticket). That said, given the overall hilarious appearance

of the Caponians (who prefer to masquerade as a cross between Groucho Marx

and Super Mario), the threat of capture makes you more fidgety than terrified

— there’s really no space for proper «nightmare fuel» in a LucasArts game,

even despite all the actual nightmares that Zak has to go through every time

he goes to sleep. |

||||

|

Technical features |

||||

|

Graphics

One big advantage, however, that Zak McKracken holds over Maniac

Mansion is that it was lucky enough to be eligible for re-release on the

Japanese market for Fujitsu’s FM Towns computing systems, which had native

VGA resolution with 256 colors and used CD-ROM technology, allowing for

better audio. Of course, back in 1990 only the Japanese buyers, or those

lucky enough to own an imported model, could enjoy the game in such a

revolutionary format; today, though, when everything back from the 20th

century is only played through emulation software, the FM Towns version is

just as easily playable through ScummVM as the original EGA version, and for

retro-gamers, it has pretty much replaced the original (for instance, it is

the FM Towns version that is being sold on GoodOldGames as the default

option). It’s not exactly a stupendous upgrade, and there are a few

graphic perks to the enhanced DOS version that the FM Towns one somehow lost

in transition; careful comparison of the actual frames shows that some

details have been cut out or smoothed over, and sometimes the simple colorful

vibrancy of EGA gives out a brighter and cozier vibe than its shade-of-grey

replacement in the VGA version. On the whole, though, the FM Towns variety

unquestionably offers more depth to the experience, and I can easily confirm

the recommendation as first choice, with the enhanced DOS and the Amiga

versions lagging not far behind. As in Maniac Mansion, the

verb-based interface continues, unfortunately, to eat up about a third of the

screen, making the game’s locations unroll as a sort of narrow scrolling

tapestry — also the same principle as in Maniac

Mansion, except that this time around, you really spend most of your time

either in the open air or inside mazes and corridors, so the scrolling is

pretty much ubiquitous. The art style is relatively generic and perfunctory,

but the images do their job well enough — the Pyramids do look imposing, the

red Martian desert does look mysteriously haunting, and the Katmandu temple

area does look rather outrageously gauche and tourist-ey. Not really sure

what else can be said here. |

||||

|

Sound This, even more so than the

graphics, is where the FM Towns version really comes to life. The DOS version,

like Maniac Mansion, was only

accompanied by PC speaker support, so it stayed silent for most of the time,

and when it didn’t, you most certainly wish it would — the opening music

theme and the few sound effects scattered throughout have hardly aged well

when represented by bleeps and beeps, to put it mildly. With full CD-ROM

support, however, the 1990 version was able to feature a full musical score

(unfortunately, no speech), and although the main theme still sounds terrible

when converted to MIDI (like one of those «kick-ass» electronic dance

compositions in the opening titles to Eighties’ police dramas and porn

flicks), the rest of the soundtrack is not too shabby. Well, actually, it is

pretty shabby, because the dynamic musical segments usually play like

forgettable elevator muzak. But the bits that are more ambient in nature play

pretty darn well, nicely reflecting local styles (with expectable sitars in

the Katmandu section, congas and bongos in the Central African section, and

swirling psychedelic flutes in the Egyptian section). From a purely audio

perspective, the best segment would probably be Mars, with haunting gusts of

wind adding to the overall spookiness of the desert and mystical ambient

soundscapes resonating across the corridors of the huge Martian maze. If the

main musical accompaniment to the game cannot be said to have properly

survived the judgement of time, the sonic ambience of it is atmospherically

admirable even today. Playing the game on mute during those segments really

takes away an entire dimension, which is ultimately the reason why the DOS and FM Towns versions play like two

different experiences. |

||||

|

Interface

While

there is absolutely nothing wrong with two or more games running on exactly

the same version of the engine — Sierra did that in droves, though,

admittedly, their business model allowed them to pump out far more product

over a year-long period than LucasArts — it’s still a little symbolic of Zak McKracken’s downfall: for all the

different vibes it gave, things like that only reinforced the general feeling

that it was really just an unimaginative clone of its predecessor. For quick comparison,

already the year after that Indiana Jones

And The Last Crusade would at least diversify the interface with a

choice-based dialog system (not to count all of its questionable, but

imaginative mini-games), and then along came Loom with all of its painfully-ahead-of-its-time features... next

to these advances, Zak does feel

like a clone when it comes to pure gameplay. Fortunately for it, innovation

in gameplay mechanics is just about the very last parameter on my mind in

calculating the overall enjoyability of a gaming experience! |

||||

|

Verdict: Definitely not enough to save the world from stupidity,

but does at least give you something to think about. It is difficult for me

to make an unconditional recommendation for Zak McKracken & The Alien Mindbenders. On the technical

front, it is such a blatant imitation of Maniac

Mansion that it hardly has any place in the history of video game

evolution. On the «fun» front, it can be confusing and frustrating even for

the seasoned retro-gamer — not only because it is a rare case of a LucasArts

game where you can unexpectedly die or, worse, get stuck in a dead-end

situation, but also because of its seemingly austere approach to clues and

ugly mazes. It’s really easy as heck to build up a condemning case here and

state that, for a brief while, the studio «lost its way» before the next wave

of successful innovations came along. And yet, at the same time, I still

feel a bit of genuine fondness for the universe built up by David Fox — a

more expansive, meaningful, and mature take on the absurdist realities of Maniac Mansion. I like how the mundane

and the surreal, the entertaining and the educational, the idealistic and the

sarcastic bits intertwine with each other; how the game, while never

officially taking itself seriously, subtly implants the almost religious idea

of everything in the universe being connected by the same laws and patterns; how

it tries to go beyond the pure, unadulterated parody of Maniac Mansion to deliver subtle hints at the

less-than-satisfactory state of humanity (note that the game action is officially

set in 1997, a mere decade into the future). That tiny cult of Zak McKracken

fans that still persisted until at least the 2000s (the German fan game Zak McKracken: Between Time And Space

was released in 2008 and remastered in 2015), I am sure, owes its existence

to pretty much the same feelings, rather than any formulaic admiration for

the game’s mechanics and «fun factor». Perhaps — who knows? — that

intermingling between Fox and Gilbert did, after all, result in compromising Fox’s

original vision, and perhaps Zak McKracken

could have come out even better, had it adopted a more serious tone. One of

the most common criticisms of LucasArts, after all, is that the studio was

never able to produce anything but sheer goofy comedy (Loom being just about the only exception to the rule), and

theoretically I could see somebody like Fox diversifying its portfolio. But,

first of all, this is just speculation, and second, it’s just as possible

that the game would have devolved into pedantic and insipid «edutainment»

instead. As it stands, Zak McKracken

is the kind of game that invites you, every once in a while, to stop and

think about its content rather than just concentrate exclusively on beating

its puzzles and getting the final achievement of «saving the world from

stupidity» without bothering to think about the metaphorical implications of

your actions — or, at least, about the true nutritional values of two-headed

squirrel burgers. |

||||