Pink Floyd

Pink Floyd | Release date | Label | Producer | Genre | Length | More info |

| 1975.09.12 | Harvest | Pink Floyd | Classic Art Rock | 44:08 |

|

Funeral music for a living friend in G minor.

Background

In Pink Floyd history, Wish You Were Here is always inextricably linked to The Dark Side Of The Moon - usually in the context of a question like "what do you do when you've just released one of the most commercially succesful and critically revered albums of all time?". Somewhat amusingly, the original plan couldn't have been more different than the final results: in 1974, the band decided to go back to their avantgarde-experimental roots and release an album of musique concrete that would all be played on various household objects, from wine glasses to hand mixers. It did not work (although some of the explored effects made their way onto WYWH in the end), and perhaps it could not work - once you cross the line that separates the intellectual underground from mass popularity, you can never truly go back. However, the attempt was not totally wasted, because it still put them in a creative-imaginative mood when they started working on the real thing.

Although by 1974-75, the "progressive" streak in popular music was beginning to wear thin, with critical admiration for bands like Yes and Jethro Tull gradually turning to disappointment, the immense success of Dark Side pretty much guaranteed to make Floyd an exception to the rule - but only as long as their epics "made sense", which meant having lyrics that ordinary people could relate to and, in its melodic base, not stray too far away from the basic blues idiom. So what do you do when you have all these invisible constraints imposed on you, and also find yourself obliged to prove that your recent masterpiece was not just a happy fluke?..

Some basic factsBesides the usual suspects (Roger Waters - bass, guitar, vocals; David Gilmour - guitars, keyboards, vocals; Rick Wright - keyboards; Nick Mason - percussion), the sessions also marked the return of Dick Parry on saxophone, and featured Roy Harper as guest lead vocalist on ʽHave A Cigarʼ, which somehow neither Waters nor Gilmour decided was suitable for their voices (a strange decision, since there's not a great deal of vocal difference between it and, say, ʽMoneyʼ, but they probably knew better). Alan Parsons was too busy with his new band to engineer the project, but Brian Humphries, his replacement, did a fine enough job. And, of course, one can never write about this album without mentioning the June 5, 1975 visit of the ghost of Syd Barrett into the studio: although they were already finalizing the mix of ʽShine Onʼ at the time, I have no doubt that some of the feelings experienced by everybody on that day must have somehow, in some way rubbed off on at least some parts of the album.

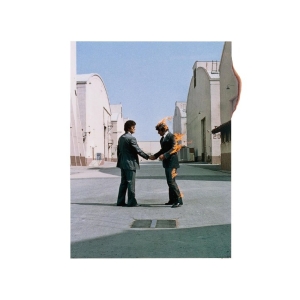

Commercially, the record stood little chance of ever outselling Dark Side Of The Moon - with but five songs on it and a smaller variety of covered topics, its appeal would be less obviously universal. Nevertheless, unlike Dark Side, it actually reached No. 1 both in the UK and in the US, and garnered almost as much praise as its predecessor (part of which should probably be credited to the mysterious influence of the Hipgnosis album cover). Predictably, the album has been re-released in various anniversary editions, and in 2011, like Dark Side, it also received the expanded treatment with a 2-CD "Experience" package and a huge "Immersion" box set. Compared to Dark Side, however, these packages offer comparatively less material - if you are a potential buyer, I'd probably advise hunting for the Experience set, which adds an enjoyable and historically significant live sub-set from the 1974 Wembley concert (with the three abovementioned early tracks performed in a row); an excerpt from the "Household Objects" project, which will help you see how the wine glass experiment was eventually woven into the textures of ʽShine Onʼ; a Waters/Gilmour sung version of ʽHave A Cigarʼ; and a ʽWish You Were Hereʼ with none other than Stephane Grappelli guest-playing a violin part that they later erased because it did not fit in with the overall mood of the song. (Incidentally, Grappelli was recording with Yehudi Menuhin in an adjacent studio on that day, but when challenged to improvise, Yehudi declined - classical violinists are such party poopers next to jazz ones, right?).

For the

defense

None of that would matter per se, of course, if ʽShine On You Crazy Diamondʼ - all the 25 minutes of it, split in two - weren't one of the most quintessential musical pieces of the 20th century. If I were to compile a personal "Top 10 Most Aching Moments in Pop History" list, that moment in 2:08 where Gilmour's guitar enters stage dramatically to the subdued, respectful tones of the VCS3 and the Hammond organ played in unison would be among the first candidates for inclusion. That first solo, concluding part 1, without a single wasted note, makes me shiver every time, no matter how much I relisten to it - and it's not just the notes themselves: formally, Gilmour does not seem to be playing anything particularly outside of the standard Claptonesque blues idiom. Rather, it is the fatherly care that goes in each single note - the tone, the duration, the reverb, the relative strength of the pick; this is true mournful bliss that is all built on cliches and overcomes every one of it. The same goes for the famous four-note "Syd theme" that follows. Its timing is perfect - give a little time for the previous solo to soak in and the keyboards to slowly fade out a little, then make a second grand entrance with a laconic musical phrase that sounds like a triumphal fanfare, a warning alarm, and a meditative mantra all at the same time. It's one of those "everybody rise!" moments where a minimal, but genius effort is made to let you know that this is going to be important, as in really important - a tale of something grand and terrifying, even if you're not aware of the details.

Some people have complained that the composition is stretched out too much - that the vocals come in much too late, for one thing (a complaint that Gilmour partially recognized by agreeing to delete one of the guitar solos on most of Floyd's post-Waters live shows). Maybe it is, and maybe two similar-sounding guitar solos, interrupted by a keyboard solo, give undue advantage to Gilmour's guitar voice over the rest of the band - but there is not another track in Floyd's entire repertoire that would be comparable in human sentiment and transcendental majesty at the same time (ʽComfortably Numbʼ is, after all, an arena rocker first and foremost, and does not have as much "internalized emotion"). Besides, it's not as if he's noodling all over the place for hours or anything, and both Wright (on keyboards) and Waters (on vocals) pay their equally comparable share of the tribute, not to mention Parry's sax solo.

The idea to split ʽShine Onʼ in two did not have Gilmour's initial approvement - but in the end, it turned out to be an excellent move, because of the possibility to arrange those following two songs as "flashbacks". ʽWelcome To The Machineʼ, due to the nature of its metaphor, is as close as Floyd ever came to creating an "industrial" piece of music - of course, it uses all of its noisy ideas as a setting for the dark-folksy melody rather than a goal in itself, but isolate the synth loops and all the steamy explosions and you get yourself quite a scary experimental track that could easily hold its ground against any Cabaret Voltaire or Throbbing Gristle track. ʽHave A Cigarʼ, on its own, is not a great song - it has a fairly common blues-rock riff, Harper's vocals aren't particularly affected by any kind of emotion, and on the whole, this sort of aggressive-frustrated blues railing would only be perfected by the band for Animals. But it's still decent enough, and it obviously works as part of the story - in fact, I like to picture ʽWelcome To The Machineʼ as a long, creepy, but breathtaking elevator journey to the top of The Factory, with the souls of miriads of unfortunate victims trapped on the countless stories; and then, at the very top of it all, you are greeted by the Uberboss, a somewhat ignorant ("by the way, which one's Pink?"), but totally efficient Lucifer model in its own right. (Maybe they should have brought in Alice Cooper to sing the song instead. Or Meatloaf.)

Ideally, the transition from the "flashbacks" back to ʽShine Onʼ, I think, should be made before ʽWish You Were Hereʼ rather than after it - it is just so natural when The Fallen Hero's journey to the top segues right into the chilly wintery winds of Part 6, and how we have that ominous part, highlighted by the reverberating bass and Gilmour's Evil-Joker-style slide solos and representing the devilish fate that awaits The Hero, finally seguing into the last reprise of the vocal section: "Nobody knows where you are, how near or how far...". In my own (if I may be so bold) ideal vision of the album, the title track is the post-scriptum - something to be quietly hummed to the soft strum of the acoustic after the ceremony has ended and the last of the stunned spectators has left the building. Then comes the moment when, out of nowhere (or, to be more precise, out of the lo-fi crackle of a radio transmitter), you get this last bit of homely, cozy, intimate respect for the departed. I guess there must be a certain logic to the sequencing that we have, but I have a harder time perceiving it. Not that it's a big problem or anything.

A final special mention should probably be made for the "effects" - in particular, the use of the glass harp on the opening segments of ʽShine Onʼ, which went all the way back to the failed "Household Objects" project, but fit in so wonderfully here: clearly, the tinkling glass effects are in agreement with the "diamond" thing, adding one more sonic allegory on top of everything else. When you listen to those bits in headphones, as loud as possible, you can actually picture yourself in some sort of majestic funeral chamber, with dazzling-sparkling diamonds everywhere and the proverbial Napoleon's Tomb in the middle. Also, there's no other Floyd album on which they would put the VCS3 to better use - their electronics now are alternately God-like and Devil-like whenever they choose: more generally God-like on ʽShine Onʼ, totally Devil-like on ʽWelcome To The Machineʼ - remember that creepy whizz at the end of the ascending acoustic guitar solo? You're going up there, floor after floor after floor, and then the industrial wind hits you flat in the face at the top, as you get your general view of the grim robotic panorama. Ultimately, all these "gimmicks" have their proper purpose, and remain inseparable from the melodic base of the album.

For the prosecution

Conceptually, the record also loses to both Dark Side and Animals in terms of scope: where Dark Side was dealing with nothing less than the meaning of human life in general (yay, pretentious!), and Animals laid out a whole socio-political vision (hardly an original one, but very originally encoded in animalistic and musical metaphors), Wish You Were Here relates to a more narrow, specific situation. But then again, so did Citizen Kane, which never prevented it from becoming a masterpiece not only for conceptual reasons - and besides, who'd really want to put down a musical record merely because it is less conceptually ambitious than any of the surrounding pieces?.. Not really. Much more problematic is the fact that the vocals throughout aren't all that good, be it Roy Harper or Roger Waters, yet even that can sometimes turn to the band's advantage (for instance, Waters' somewhat annoying "wailing" on ʽMachineʼ is perfectly suitable if you imagine that it is being collectively delivered by all the miserable souls trapped in The Factory, communicating with our hero telepathically as he rides up in that goddamn elevator: warning given, but not heeded).

Conclusion

Overall, I'd say, this is an album that every one of us wishes (or should wish) he/she could have it played in its entirety at our funeral ceremony - but then most of us probably have to deserve that right, and if the necessary pre-requisite is getting a welcome from The Machine and a cigar from Roy Harper, then maybe we'd rather not.

| Melody |

Voice | Mood | Production | Innovation/Influence | Where it belongs | RYM preference | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

#4 (Jan 24, 2016) |

| Previous entry | Main page | Next entry |