Bob Dylan

Bob Dylan

| Release date | Label | Producer | Genre | Length | More info |

| 1965.08.30 | Columbia | Bob Johnston | Modernist Rhythm & Blues | 51:26 |

|

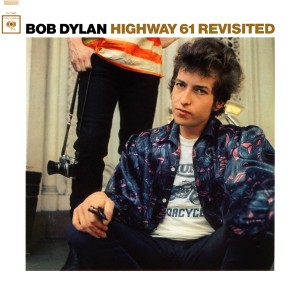

The look that launched a thousand hipsters.

Background

June 16, 1965: Dylan and his band record the definitive take of ʻLike A Rolling Stoneʼ. July 20, 1965: ʻLike A Rolling Stoneʼ is released as a single. July 25, 1965: The Newport Folk Festival and the infamous "Dylan publicly going electric" incident. July 29, 1965: Dylan is back in the recording studio to generate the rest of Highway 61 Revisited, only four months after the previous record had hit the record shelves. Yes, you could say things were moving quite fast at the time, but nobody really complained - well, Dylan would mention every once in a while how he was really tired and all, but the rush was on all the same.

Of course, Dylan had already "gone electric" with Bringing It All Back Home, which objectively makes Highway 61 Revisited somewhat less of a "breakthrough" than it could have been. However, a lot of important things happened in between - most notably, the release of The Byrds' version of ʻMr. Tambourine Manʼ as a single and then of the complete LP; the release of the Stones' ʻSatisfactionʼ in June; and, right as Bob was re-entering the recording studios, the Beatles came out with ʻHelp!ʼ (the single) - and these were only the major events in a whole flurry of 'em that indicated: a new form of music was finally getting up on its feet and threatening to replace jazz as the decade's major intellectual-musical form. You had all those blues, folk, and jazz influences permeating the melodies - and you had completely new approaches to lyric writing, be it in surrealist or socialist form.

Now Bringing It All Back Home could be a pretty awesome flagman of the change, but it was still too deeply rooted in the folk tradition (its second side being all-acoustic), and most of its electric songs seemed to be knocked off too fast. Serious, innovative, mind-blowing singles were being released on a permanent basis now, with the Brits still largely leading the way and the Americans catching up, but until August 1965 the industry still lacked a long-playing record that could proudly say of itself, "I'm all for grown-ups". Even Help! the LP, arriving on the shelves in early August, was still very much a transitional effort - it had many subtle musical breakthroughs, for sure, but word-wise and mood-wise the Fab Four still mostly wanted to hold your hand and act naturally. The Byrds, too, were still young and inexperienced and when it came to synthesizing the folk tradition with the pop format, they adapted the former to the latter instead of vice versa. The Rolling Stones still earned their meat and potatoes covering Chuck Berry and Marvin Gaye, and only their desserts writing original singles. In the end, it still fell to Dylan to complete whatever it was he'd started.

Some basic factsSince Dylan albums usually detest and despise bonus tracks, the absolute majority of Highway 61 editions come clean, clocking in at the original (very unusual at the time, especially for America) length of 51 minutes; it could be argued that the singles ʻCan You Please Crawl Out Your Window?ʼ and ʻPositively 4th Streetʼ very naturally belong here - but I guess nobody wants the album to end on anything other than ʻDesolation Rowʼ, so you'd have to insert them rather than append them, and that would mess up the original masterplan. Of course, in this age of digital downloads nothing like that is a problem any longer, but if you still think in LP or CD terms, for a long time you could get those two only on compilations like the Biograph boxset. As for the rest, given the historical importance of those auspicious days, pretty much everything that the band recorded back then, including aborted takes etc., is now available on the deluxe 18-CD edition of The Bootleg Series Vol. 12: The Cutting Edge, so if you want to study genius under a microscope, it goes for only $113 on Amazon these days (and, of course, a true fan wouldn't settle for anything less than the complete package on CD or vinyl). That said, if you are unfamiliar with the way the Dylan thing used to work - keep in mind that this was nothing like Beatles perfectionism: most of the takes were done live, and the best one could often be the first one, or close to the first one, so in many cases you will be listening to dead end branches, not "progressive embellishment and development".

Upon original release, Highway 61 went all the way to No. 3 in the States, vastly outselling all of Bob's acoustic output and providing objective proof to electric Dylan detractors that the man had "sold out" to a mush-brained pop audience. These days, people tend to look at it the other way - that the release initiated a bright, optimistic period in pop music history when thinking, creative, innovative artists influenced mass taste, rather than the opposite direction that arose in the Seventies and pretty much stiffed and "under-grounded" creativity by the Eighties. In reality, it was sort of a compromise between the two, but whatever Dylan's real motives may have been, "selling out" was clearly not one of them: he obviously wanted to make his mark on the world and to be precisely at the place where it was really happening, but he was never after "pure" fame or fortune: Highway 61 is a clear case of "selling in", not "selling out", with one man establishing his own paradigm and symbolically telling you, the average Joe, that you must be an idiot if you're not buying into this.

For the

defense

Since I have already written at least two extensive reviews of Highway 61, I find myself pretty much out of good things to say about the songs. So I'd like to completely give this section over to a recent fun observation on how the nine songs of the album actually work in intertwining groups of threes (with a bit of fact-forcing cheating on the side): 3 songs about Me, 3 songs about You, and 3 songs about Everything Else In Between.

The ʻMeʼ songs are the laziest of the lot. People frequently (and not unjustly) accuse Dylan of misogyny, misanthropy, a condescending and antipathetic attitude towards everybody else in general, but let us not forget that he can be his own worst enemy, too. ʻJust Like Tom Thumb's Bluesʼ is essentially a song about being helplessly stuck and confused in time and space, its repetitive structure resembling static waves that lock you in some sort of force field you can't escape - "lost in the rain in Juarez", "I cannot move, my fingers are in a knot", etc. ʻIt Takes A Train To Cryʼ never seemed to work as long as they kept it speedy, but once they slowed it down to a halt - the slowest moving train on this planet - it began to agree perfectly with lines like "I went to tell everybody, but I could not get across". It's another song, really, about being nowhere and doing nothing. And ʻFrom A Buick 6ʼ? It's a song about a guy who has nothing, needs nothing, and the only thing, really, that he needs is a "graveyard woman" that's "bound to put a blanket on my bed".

The ʻYouʼ songs are the meanest of the lot. Mr. Jones from ʻBallad Of A Thin Manʼ has it worse than everyone else, but the unnamed female protagonist from ʻRolling Stoneʼ is not far behind, and the other female character from ʻQueen Jane Approximatelyʼ is the only one to deserve a little genuine pity, but not until she's found at the complete end of her rope. The most fun thing to do is to piece it all together - remember, the exact same guy who invites the unfortunate Queen Jane to come see him is the one who cannot move, because his fingers are in a knot; where is she supposed to meet him - all lost in the rain in Juarez? And maybe it doesn't feel that nice to be on your own, with no direction home, but hey, it's still better than dying on top of the hill.

The ʻEverything Elseʼ songs give you the environment - from the urban hustle-bustle of ʻTombstone Bluesʼ to a sample of humanity's biggest problems on ʻHighway 61 Revisitedʼ to the much more relaxed and monotonous pace of life in the alternate universe of ʻDesolation Rowʼ. The first two of these songs are hyper-active, contrasting very deliberately with the more leisurely and reclusive style of the ʻMeʼ part (you could say that ʻTombstone Bluesʼ also interacts with the ʻMeʼ universe, since it's written from a first-person perspective; but here, the protagonist is never the focus of attention, more like an outsider cautiously surveying the hullaballoo from his vantage position in the kitchen). The third one, however, is homely-Utopian in contrast, as if saying, "relax and calm down, Desolation Row is where we're all gonna end up anyway", and so it kind of ties together all the themes, because you can easily see the girls of ʻRolling Stoneʼ and ʻQueen Janeʼ, the alternate historical personages of ʻHighway 61 Revisitedʼ, and the dysfunctional hero of the ʻMeʼ songs all sharing a cozy condominium on the same street, next to Cinderella, Romeo, Casanova, and the Good Samaritan.

Of course, this is just a personal interpretation stemming from years of listening: Highway 61 Revisited is not a proper "concept album" or anything like that. But there's no question about its individual songs all feeling like a part of some tightly organized whole, and this is also why I cannot really divide any of the tunes here into lowlights and highlights - even a relatively "minor" composition like ʻFrom A Buick 6ʼ, which never finds itself near the top of anybody's favorite Dylan songs, has a perfectly valid reason to be here. As far as I can tell, this is simply the first album in rock history that creates its own universe and makes it come alive before your very eyes - without it, there'd be no Sgt. Pepper, no Electric Ladyland, no Close To The Edge and no OK Computer, to name but a few worthy successors. And it's not just the lyrics, either: much of the album's surrealism, escapism, and futurism is indirectly reflected in the music itself, from the crude haunting sounds of Bob's electric piano to the little flamenco flourishes on ʻDesolation Rowʼ. But that is a much longer story, parts of which were already told in my previous takes on the album and other parts of which I just don't feel like exposing right now.

For the prosecution

"I wish I could write you a melody so plain", but I'm actually quite stumped at the idea of being obliged to criticize Highway 61 Revisited. Should I state that Bob Dylan's voice is an acquired taste? That some of these songs rely too much on generic 12-bar blues structures as their basis? That almost each of them could be cut by at least one or two verses without substantial damage to the whole? That that "give me so milk or else go home" line makes no sense? That Bob's haircut on the album sleeve looks almost New Romantic fifteen years before New Romanticism started? All these are perfectly legit observations, but each one is immediately neutralized with a "so what? that's all part of the masterplan", and I can't help agreeing with that, because it is, and it's a perfectly valid and efficient masterplan, too. I don't believe in dissecting this record - it's a matter of either total acceptance or, for those born with an innate deficiency of dylanite, total rejection.

Perhaps the worst thing I can say about Highway 61 is that I still consider it a little more crude, blunt, and superficial than Blonde On Blonde, even if this makes it more appealing for fans of energetic, kick-ass rock'n'roll worldwide. But "depth" and "subtlety" are not the only values according to which one should judge art - Highway 61 is simply the hustle-bustling busy day that eventually descends into the more introspective nighttime of Blonde On Blonde, and pitting them against each other is ultimately irresponsible, not to mention that it could lead to the lazy novice getting to hear only one of them, but not the other - a crime punishable by 10,000 years of postmortem wanderings in the wasteland of Bad Taste.

Conclusion

| Melody | Voice | Mood | Production | Innovation/Influence | Where it belongs | RYM preference | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

#15 (Apr 10, 2016) |

| Previous entry | Main page | Next entry |