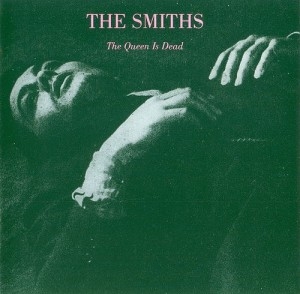

The Smiths

The Smiths

| Release date | Label | Producer | Genre | Length | More info |

| 1986.06.16 | Rough Trade / Sire | Morrissey / Johnny Marr | Art Pop | 37:05 |

|

1986: The Smiths: "The Queen Is Dead". 1987: The Queen: "The Smiths Are Dead".

Background

In 1986, The Smiths had already been on the roster of the UK's biggest contemporary heroes for two years - yet somehow, record buyers and critics alike seemed to have a feeling that the quintessential Smiths album was still waiting around the corner, or else they would not have all fallen upon The Queen Is Dead like vultures on a fresh piece of carnage. Why did Britain have such a turbulent love affair with The Smiths in the first place? Supposedly, the country had to have its own popular answer to the folk-based "college rock" of the likes of R.E.M., something that would be jangly, simple enough to be commonly accessible, and yet presenting a highly contemporary (and preferably "artsy") vision of the locality. The Morrissey/Marr team, supplying the sounds and the substance, could do just that, and even beat American competition in terms of that elusive strand of noble European romanticism that earth-bent Yankees usually tend to avoid.

The Smiths had all that and more on their first two albums, but one thing that was quantitatively insufficient on The Smiths and Meat Is Murder was ambition: the songs were well written, but they sort of lacked a visionary / prophetic kind of depth to them, which, given Morrissey's tendency to drop all sorts of cultural references and to associate his personal demons with the bigger demons plaguing the entire country, would certainly have been expected. In other words, they had not yet produced something properly big enough - something that would fix them up permanently as a living legend and maybe end up as the defining "English album" of the mid-Eighties. And, well, you just know it that when the record comes out with a title like The Queen Is Dead (not even the Sex Pistols were that rude, even if formally, this is just a quotation that has nothing to do with Elizabeth II), not to mention featuring a 1964 Alain Delon on the front cover, the stakes have certainly been raised. So is that it? Is this really the biggest English album of the decade? Read on to find out.

Some basic factsCritical appreciation of the record has always been on a high level, but it seems that the accolades are mounting in almost geometric progression - a case in point is the year 2013, when an NME poll officially ranked The Queen Is Dead as the greatest album of all time, which just goes to tell you how much The Smiths are regarded as a national treasure in their native country. All the more curious, by the way, why there has never (as of yet) been any "Anniversary Edition" to speak of, with lots of bonus tracks, demos, outtakes of the boys fighting in the studio, etc. Particularly considering that we are very, very close to the 30th anniversary now and all that. Then again, we all know what a humble and reclusive soul Mr. Morrissey is, and the last thing he'd probably want to inflict on us would be the rough drafts of his philosophical etudes...

For the

defense

First things first: compared with the first two albums (and especially the band's self-titled debut, which remains my personal favorite), The Queen Is Dead is very much a "Morrissey" album, where the role of Johnny Marr as an innovative contributor of sounds, tones, and effects is drastically reduced. Other than the title track, a perfect example of post-punk melodicity, I don't think any of these songs would have made much of an impact had they been instrumentals - this is first and foremost a set of confessional / psychological tales from one of Britain's most gifted lyricists and most exuberant performers, and if you happen to be in the "love Johnny Marr, despise Morrissey" camp, I'm pretty sure you won't be head over heels in agreement with that NME poll. The bright news is that Morrissey is really, really good on this particular record.

Essentially, he is painting here one of those "I-just-wasn't-made-for-these-times" self-portraits that manages to avoid the emotional extremes of punkish aggression or Gothic suicide tendencies, and instead speaks for the "average intelligent guy" who is just too smart and too sensitive to fit in anywhere, be it the government (ʻThe Queen Is Deadʼ), the capitalist establishment (ʻFrankly, Mr. Shanklyʼ), religion (ʻVicar In A Tutuʼ), classic poets (ʻCemetry Gatesʼ), girlfriends (ʻBigmouth Strikes Againʼ), and even himself - I mean, what's a guy to do when, upon finally having located that special one, his ideal is dying together in a double-decker bus crash (ʻThere Is A Light Than Never Goes Outʼ)? And it's all believable because it all must be honest: quiet, but stern dissatisfaction with just about everything is at the heart of this record as it must have been at the bottom of Morrissey's soul at the time (and frankly, Mr. Shankly, not much has changed since, except that the man has grown much more mean and much less romantic).

At the same time, all these poetic confessions are also pop songs, and have a transparent commercial angle: Morrissey was not about passing himself for a reincarnation of Tim Buckley, and even when he is at his deepest and most starry-eyed, he remembers to saddle the power of a well-placed, much-repeated vocal hook. "Oh mother, I can feel the soil falling over my head"; "never, never had no one ever"; "Keats and Yeats are on your side"; "there is a light and it never goes out"; and even "some girls' mothers are bigger than other girls' mothers" - these are cleverly constructed and performed chains of sound-meaning that will stick in your head even if you are emotionally indifferent to the sound and/or intellectually hate the meaning. Is there beauty in these lines? Could be, except that The Queen Is Dead is not an album about beauty - it's more of an album about a frustrated and hopeless search for beauty, very specifically designed for a very specific, sensitive, vulnerable kind of mind (well, more or less the same kind of mind that would a decade later be feeding on Radiohead, I guess - and yet another decade later, would be taken to new and almost grotesque heights of theatricality by Anthony and The Johnsons).

As the (still) loyal sidekick, Marr is quietly layering his guitars at Morrissey's side; it is almost surprising, considering the tension between the two, how little he is trying (if he is trying at all) to steal the spotlight away from the gloriously literate frontman. Texture-wise, his sole moment of solitary glory is on the title track, which could have easily been about three minutes shorter than it is if Marr had not extended it with a lengthy jamming section, rocking his heart out on several overdubbed funky parts - it's cool, but a little deceptive as the opening track, and not all that outstanding. Everywhere else, his contributions are more subtle, and take a long time to be properly appreciated, as they essentially function like elegant flourishes, woven around the sound of Morrissey's voice, and their effect is often cumulative: for instance, no single instrumental part on ʻNever Had No One Everʼ properly stands out, but together that little touch of echo (or is it flanging?) on the acoustic guitar, the minimalistic keyboard riff, and several additional minuscule overdubs (like that odd whistle sound that comes in at certain points in the song) greatly enhance the melancholic feel of the song.

However, my absolute favorite of Marr's on this album is the paper-thin sound (a little Cure-like) that he gets on ʻSome Girls Are Bigger Than Othersʼ - curious, that one, because the tune in general seems to be more of a joke number that Morrissey used to bring down the puffed-up emotionality of ʻThere Is A Lightʼ a little bit, and there you suddenly have it: a sharp, "autonomous" (that is, functioning relatively free of the need to be accommodated to Morrissey's voice) folk-rock guitar part that brings up fond reminiscences of all the neat guitar tricks that Johnny inserted on The Smiths and which, to tell the truth, I am sort of missing here.

For the prosecution

Okay, so you probably already guessed that one: the songs, as individual musical compositions, are just... not that strong. Granted, jangly folk-rock has a hook problem by definition (R.E.M. are no different from The Smiths in that respect), but, like I said, too often on these songs Marr seems to be reduced to the position of "accompanyist", and as pretty as ʻI Know It's Overʼ is on the whole, I fail to see anything interesting about its musical composition - a pretty standard chord progression there, and not a lot of ear-candy in terms of arrangements, either. As sacrilegious as it sounds, I just don't see what makes the instrumental backbones of at least half of these tunes any more awesome than, say, 10,000 Maniacs. Stylistic diversity is not a forte of The Queen Is Dead, either: I did not even notice that ʻVicar In A Tutuʼ borrows from the rockabilly genre until my third or fourth listen, because the "rockabilly guitar" is picked so smoothly and gently that the sound is still reduced to that common jangle-pop denominator.

Honestly, the record is much more about atmosphere (even if I'm slowly growing to hate that word) and vocal hooks than it is about memorable instrumental melody - which is not a problem at all, but would certainly disqualify the record from ever making it into my own personal Top 20-50-100, let alone "greatest album of all time". If you need a comparative angle, well, take something like ʻHand In Gloveʼ from the debut album - starting out with an almost instantly memorable acoustic riff (not to mention how well it is supported by the harmonica part), next to which Morrissey's vocals sound like an embellishing afterthought. On The Queen Is Dead, the situation is reversed: the vocals always take precedence, while the instrumental melodies tend to either be too quiet, or too "lazily" syncopated, or simply too generic. And you could hardly blame Morrissey for that, since he did not have a lot of say over Marr's musical decisions. As it is, the legend of The Queen Is Dead seems to be way too heavily based on word imagery and psychological depth rather than, you know, chords and notes. Which is understandable (we're all human), but... gimme just a little bit more music, if you please, and then I'll be joining the choir.

Conclusion

| Melody | Voice | Mood | Production | Innovation/Influence | Where it belongs | RYM preference | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

#22 (May 29, 2016) |

| Previous entry | Main page | Next entry |