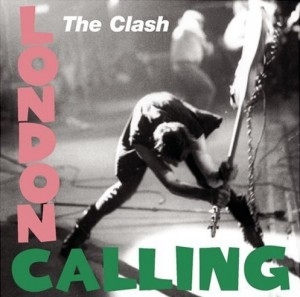

The Clash

The Clash

| Release date | Label | Producer | Genre | Length | More info |

| 1979.12.14 | CBS / Epic | Guy Stevens/Mick Jones | Pop Rock | 65:07 |

|

The London Handbook of Sociopolitical Ass-Kicking Pop Writing: A Special Gift for M. Thatcher, PM.

Background

Sometimes it actually surprises me to see how many punk rock bands never grew out of the punk phase - starting with the Ramones, who were the first to introduce the classic formula and also the first to get stuck in it for the rest of their career, and ending even with such emphatically "intellectual" punk bands as Bad Religion, who somehow thought that emotionally and intellectually shaking people up with the same formula, again and again and again, was their natural calling and obligation to their personal Muse. Most of the really big heroes of the early punk wave, however, could not stand to let their rout become a rut - and either broke up, like the Sex Pistols or the Buzzcocks (the latter only to reconvene again when it was much too late and most people were just embarrassed), or reinvented their act, like The Jam (and then broke up). The Clash, with their first two albums out, were looked upon the UK as one of the most serious punk acts around - aggressive-energetic like the best of 'em, but also focusing almost exclusively on the social and political side of things rather than wasting time on just being naughty and shocking for naughtiness' and shock's sake; and I think a statement like London Calling was, in a way, expected out of them, because for all the freshness and intelligence of the original punk formula, it was a formula, and a really smart band cannot allow itself to stagnate.

One thing in particular that punk music still had not done by 1979 was proper insemination of the non-punk genres. Of course, punk itself was largely just a toughened up update of ye olde rock'n'roll, and the Ramones could do punk-pop, and the Clash themselves already experimented with reggae on their debut album, but what the world really needed was for a punk band to go "epic", to retain that new, vibrant punk aesthetics and apply it to decades of preceding musical tradition - go global with the thing and show the world that the new "fad" is really the beginning of a new era of popular music, that this "punk aesthetics", like it or not, will come and stand at every door, because it's not just about the chainsaw buzz and the barking vocals and the stupid hairstyles. And many people were expanding at the time (remember, even The Police started out as a punkish band and carried a brand of that flame throughout their entire career all the way to Synchronicity), but there was no single, irresistible symbol of the big change; looking back at all the wonderful albums from 1976-78, I'm really hard pressed to find something as ambitious as London Calling executed by one of the recent bands. No wonder - punk rock in general was a return to the "lesser scale", an attempt to bring rock music back to the streets and the pubs from arenas and TV studios, and bands consciously avoided making "big", "pretentious" statements (even the sheer length of it - I have no wish to insist that London Calling was punk/New Wave's first double LP, but off the top of my head, I can't think of any that preceded it). The Clash were the first to take that chance - to make one of the most pretentious statements of complete unpretentiousness - and, fortunately, also the first to succeed at that.

Some basic factsThe band's classic lineup for the sessions consisted of: Joe Strummer (John Graham Mellor, for all our FBI and CIA readers) - vocals, rhythm guitar, piano; Mick Jones - lead guitar, piano, harmonica; Paul Simonon - bass guitar; Topper Headon - drums. Ambitiousness of the project led to the necessity of some extra session musicians: Mick Gallagher (normally with Ian Dury and The Blockheads) on organ, and a special brass section (The Irish Horns). Guy Stevens, the former president of the Chuck Berry Appreciation Society, the original manager of Mott The Hoople and one of rock'n'roll's unsung wild guys, was responsible for the production, although it is unclear what his role was precisely, beyond sharing his knowledge of the rock'n'roll treasury and some crazy enthusiasm with the boys. In any case, they were polite enough to credit him for the success of the album, which did chart a bit lower in the UK than Rope (even if they did press the label into selling it at the price of a single LP), but, on the other hand, marked their American breakthrough. (The Americans were quite gallant in their gesture - if London's calling, New York should be answering).

If there ever were any negative reviews of London Calling, their authors must be lying at bottoms of ponds with millstones around their necks: the response seems to have been overwhelmingly positive from the start, and ever since 1980, London Calling has remained a perennial critical favorite - although in recent years, it, too, has suffered from a bit of a backlash like most double albums eventually do, and some people have even cautiously suggested that, perhaps, it is not nearly as diverse and all-encompassing as some people (sometimes involuntarily) would make you think. There's also this tricky matter of The Clash, at one time, overshadowing just about everybody else with their massive weight (they were, after all, billed as "The Only Band That Matters" for a while), and as their mass popularity thins out with the passing of time, choosy listeners sometimes reward them with the "U2 curse". Nevertheless, I guess we still have at least until the end of the Cenozoic Era that the record truly passes into complete oblivion, so there's still some time to, you know, talk shit about it.

For the

defense

All of the albums by The Clash call to arms, and this one's so much not an exception that I sometimes feel a bit exhausted if I try to listen to it in one go - it's like a grueling 65-minute military drill where only the instructor feels fresh and enthusiastic until the very last minute. Punk, rockabilly, power pop, blues rock, funk, reggae, or dance-pop (I think ʻLost In The Supermarketʼ could probably qualify as such), everything plays with the ripped-shirt verve, and if it's not about personal frustration, then it's about how your country needs you to put it straight. That's precisely what makes London Calling so great - even if a particular song is not brimming with pop hooks, you can always count upon the passion and the nervous tension of the band's playing to pull it through. It may not be the best album of all time, for sure, but it is definitely one of the most spirited albums of all time, an album where the band learns how to hold nothing back and yields nothing less than a complete hundred percent every single time. Early U2 could be a good match for them in general, but U2 had their head high in the clouds from the very beginning, whereas The Clash have always "breathed the earth", and where Bono probably sweated out incense and myrrh, Joe Strummer sweats... well, sweat. This is some goddamn sweaty music here.

As funny as it might sound, on those occasional occasions where I find myself wanting to revisit me some London Calling, the first track to be replayed is inevitably... not the title track or any other of the album's important programmatic anthemic tunes, but ʻBrand New Cadillacʼ - an inconspicuous little cover of an old Vince Taylor rockabilly tune. Taylor's original version from 1959 was pretty cool in its own rights, but it was just a regular dark 'n' wild rockabilly tune from the Gene Vincent school. Here, in the hands of The Clash, it becomes downright dangerous, no, actually, murderous: there's practically no doubt in the listener's mind that "she ain't never comin' back" not because she ran away from the protagonist in that brand new Cadillac, but because Mad Dog Strummer actually had no choice but to chase her down the block and pop a cap or two in the bitch's skull. For a brief, killer two minutes the band becomes a pack of violent hitmen - Simonon's Bond-ian bass, Headon's shotgun drumming, Strummer's thoroughly hysterical delivery, and (my personal favorite) Mick Jones' crisp, searing machine-gun lead parts almost literally make for one of the Top 10 "basic rock'n'roll" recordings of all time. There's not a single live recording of the song I've ever heard that comes even close to capturing the same burning tension, so they must have probably rehearsed that single performance until their fingers and ears bled profusely, but it was totally worth it. And when you stop to think that the song is, after all, technically just a bit of genrist filler to complete the train-hoppin' picture... well, this is it.

Of course, most people still come to the album for its politically charged anthems, but politics is just one aspect: essentially, London Calling is all about the various kinds of frustration and breakdowns that the average Joe (Strummer) may experience those days on the streets of London Town, be they related to his Government, or to his boss, or to his friends, or to his lovers. The metaphors of war are many, the apocalyptic references plenty, and I do not consider it a coincidence that the album begins with a melodic bit (Simonon's bassline on the title track) lifted directly from The Kinks' ʻDead End Streetʼ - only, unlike Ray Davies, Joe Strummer is a fighter, not a moper, and so ʻDead End Streetʼ becomes ʻLondon Callingʼ, a song of rebellion against the status quo, and of proud self-assertion in the face of imminent catastrophe: "I have no fear, 'cause London is drowning, and I live by the river!" The fascinating thing is how you can play essentially the same melody with completely different emotional overtones - the Kinks, in ʻDead End Streetʼ, were conducting a funeral march (as also illustrated in their famous accompanying video to the song), but Simonon is wielding that bass like a semi-automatic, and everything about the song screams "come and get me, suckers, (Marx told me that) I got nothing to lose anyway!" The "...live by the river!" bit, spiralling upwards rather than downwards at the conclusion of the chorus, is defiant and desperate at the same time, and it's essential that the "river"'s sonic arch be generated flawlessly - again, in concert they could slur it, but here it's like a last, forcefully prepared and executed blast of self-defensive aggression. It's a song for all ages, and in 2016, feels every bit as relevant as it felt in 1979, be it in London or in Moscow.

That's just the first two songs (in reverse order); detailed discussion of all the emotional highs of everything else would take a lifetime, so I will limit myself to brief laudatory comments on five more of the album's greatest hooks: (1) the simple, but magically romantic and idealistic guitar riff of ʻSpanish Bombsʼ that transforms an otherwise rather silly ode to Spanish freedom fighters in the Civil War into a great anthem of hope for the future in the face of defeat in the present; (2) Simonon's "walk all over you" bassline in his own ʻGuns Of Brixtonʼ, which gives the song an air of inescapable dread and agrees perfectly with Simonon's intentionally impassionate, robotic delivery; the entire song feels like a tense walk in a prison courtyard; (3) "death or glory, becomes just another story!" - there's something delightfully creepy about the enthusiasm with which this catchy maxim is delivered over and over; (4) Mick's screechy, hysterical, somewhat Marc Bolan-esque, classic rock riffage on ʻLover's Rockʼ, Strummer's free sexual education lesson for the masses that must have solved the UK's overpopulation problem overnight (not that Professor Strummer isn't 100% accurate when he says "you must know a place you can kiss if you wanna make lover's rock"; (5) ʻI'm Not Downʼ - hell, did you notice there's another Kinks quotation here, with the rumbling train-like bassline taken directly from ʻWaterloo Sunsetʼ? (Not to mention a song title that could be construed as a retort to the Beatles' ʻI'm Downʼ, and a bit of bass quotation from ʻAnd I Love Herʼ...) ...anyway, the hook is actually the "but I'm not down, no I'm not down" line in the chorus, which, reprising the theme of the title track, can turn even the head of an old skepticist like myself with its determination.

Mind you, at least three out of these five moments are instrumental bits: London Calling is not just an album that is good because it is long, loud, rebellious, and optimistic; it is an album of well-composed or at least well-stolen songs, not particularly innovative - in fact, quite conservative with its basic melodic meat - but taking sufficient care to ensure that individual songs have individual melodies, and individual melodic phrases fit in with the mood of the lyrics. Where The Clash showed the band's composing potential, but still presented them as "punks first, musicians second", London Calling gives at least equal importance to the form and the message, and although nobody in The Clash was ever a virtuoso player (and yes, punk bands may have virtuoso players in them, no matter how efficiently they try to mask themselves), here they make the most of their playing and composing talents.

For the prosecution

I will be (perhaps unexpectedly) brief here. Instead of complaining about individual songs (which is possible: there are at least three or four that I'd define as relatively forgettable, if still powerful, filler), I will say that it is the main strength of London Calling that is also its principal weakness. Despite the formal diversity aspect, and the fact that the band was willing to experiment in a lot of directions and come up with their equivalent of The White Album, there is a certain monotonousness running through the record - perhaps best expressed in Joe Strummer's limited vocal technique: Joe is a tremendously powerful balker and barker, but there's little else he can do, and although he never balks or barks without a good purpose, eventually that shit gets a little tiresome. For all its diversity, maniacal energy, and superpower, London Calling makes the same point over and over and over, in 19 different ways. Not that I'd want them to do anything else (a tender love song? a medieval folk ballad? a progressive rock suite? God forbid!), but maybe that is why it took me so long to realize what a fine piece of rock'n'roll-soul ʻTrain In Vainʼ actually is - hidden untitled at the back of the wagon, it used to be one of those "I'd love to love you, but I feel drained already" moments. Double albums are nothing to joke with, and, considering that it doesn't really have enough material for a double album (just 65 minutes), perhaps London Calling could have been reduced... then again, it would not have that epic feel to it, so forget the whole thing.

Conclusion

So were The Clash really "The Only Band That Mattered"? As ridiculous as it might seem today, from a certain point of view and depending on what is meant by the verb "to matter", they could be, yes. In 1979, there were bands making great music without a direct social message - there were bands issuing direct messages without making great music - but there was nobody for miles around who'd be so sonically efficient and seductive in the matter of calling you to action as The Clash. And, you know, for all the efforts that young people have made over the next 35 years, I'd say that, overall, there still ain't: such a combination of musical hooks, stunning energy, genre diversity, and generally intelligent sociopolitical propaganda could only come from a very special alignment of the stars, and we're still waiting for the next one. (Come to think of it, it might be best for us to wait forever).

| Melody | Voice | Mood | Production | Innovation/Influence | Where it belongs | RYM preference | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

#29 (Jul 17, 2016) |

| Previous entry | Main page | Next entry |