|

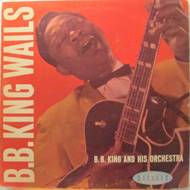

Two: the «His Orchestra» thing is no joke, as this

session does indeed feature B. B. King at his brassiest, with a huge big band

sound — huger than ever before, for sure — supporting his playing and singing.

The difference from the earlier years is, of course, mainly one of scope,

since King had always favored a big mess of pianos, horns, and (to a lesser

extent) strings behind his back, but this time he clearly wants to establish

himself as some sort of spiritual competitor for both Count Basie and Tommy Dorsey, with both of whose

orchestras he also cut several recordings that year, available as bonus

tracks on the album’s expanded CD edition. What can we say? «One of the most

polished Negro entertainers in the business», as he is called in Bill

Parker’s original liner notes,

really loved for his grit and jagged edges to be counterbalanced by glitz and

flash, the more the merrier. The problem is, the glitzier it gets, the less

convincing it becomes — for the most part, King continues to stick to the

classic vibe and feel of post-war electric blues, while His Orchestra, at the

very same time, tries to take him into a completely different direction.

Incindentally,

the contrast begins already on the very first track, ‘Sweet Thing’, which

opens as a dialog between King’s blues phrasing and a lively, blasting

response from his brass section. Like most of the tracks here, it ends up

sounding like «Big Joe Turner with Virtuoso Blues Guitar On Top», not

necessarily a great combination. When it comes to the soloing part, you’d

think the horns might step back a bit, but they actually get louder

simultaneously with the guitar, muffling its sharpness and smoothing out the

edges. The two approaches simply do not mesh all that well, which is

altogether not surprising considering that what we’re hearing is «Mississippi

Country Boy Going Vegas».

It gets even

less convincing on the second track (‘I’ve Got Papers On You, Baby’), where

the «Orchestra» does most of the work — this time, there’s a part of the

horns responsible for rhythm work and another part responsible for lead

melody — and B. B. King starts to feel like a guest star on his own

recording, playing a short, nicely flowing solo that is immediately lost in

the surrounding sea of brass. Maybe he just wanted it to be different; maybe

he was sensing his own limitations and thought that a big band like that

would be a nice way to overcome them — but I suspect that’s taking the art of

positive thinking onto a level where it simply does not belong. Far more

likely, he just wanted to put on a show. Which he did, but at the expense of

nearly dissolving his own personality inside it.

Amusingly,

there is one track on the album

with a wholly different feel from the rest — you can sense some slightly

inferior production quality on ‘The Woman I Love’ (the guitar almost seems

like it’s coming from an adjoining room), and, indeed, this is a B-side from

1954 that somehow ended up here. There’s a brass section on it, too, but a

small one, acting as modest support to the lead guitar and the rhythm

section, and King’s exuberant falsetto makes a great love duet with the lead

melody, as the artist bends, vibrates, and stings like a man possessed. It

just feels like such a natural style for him.

Returning to

the gone-glitzin’ modern era, B. B.

King Wails, in addition to regular slow and mid-tempo blues, also offers

a couple of overtly sentimental blues ballads, such as ‘The Fool’, and even

an exercise in old-fashioned doo-wop (‘I Love You So’), as well as a crude

secularization of ‘Kumbaya’, retitled ‘Come By Here’ and turned into a

celebration of lust, love, and traditional family values. Considering that

for B. B. King, the most traditional of all family values was playing his

guitar (the second was making lots of babies), we probably have little

interest in hearing him «wail» his way through the minimal vocal requirements

of "come by here, baby, come by here" without once touching the

strings, while His Orchestra is just pumping away monotonously for two minutes

and fifteen seconds.

The later-day

expanded editions of the album throw

in a couple more salvageable tracks, like a relatively vicious take on a song

called ‘You’ve Been An Angel’, or the original take on King’s «confessional»

number ‘Why I Sing The Blues’, or, most importantly, his collaboration with

the Count Basie Orchestra on a five-minute long slowed-down version of

‘Everyday I Have The Blues’ — again, King prefers to simply sing here without

touching his guitar, but at least he gets to see what a truly tasteful jazz orchestra sounds like:

graceful, giving ample space to individual players while never trying to

drown out the singer and keeping the flash’n’glitz factor to a minimum.

Perhaps if he’d recorded the entire album with Count Basie rather than his own «orchestra», things would be

different. As it is, this period in B. B.’s career seems more important from

a purely historical perspective than in terms of general enjoyment.

|

![]()