|

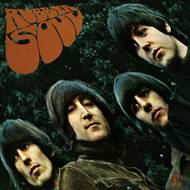

On the cover of Rubber Soul, even if, technically, it

was shot by the very same Robert Freeman who took all their pictures starting

with With The Beatles, the Fab

Four look like they finally get to look like what they really are — four

Merry Men from Sherwood Forest, although, for lack of a proper travel budget,

the back garden of John Lennon’s estate in St. George’s Hill had to

substitute for the real Sherwood. Seriously, though, it is the very

«wilderness» of the shot that provides most of the contrast with previous

photos — not just the dense green foliage, but also the Beatles’ velvet

autumnal clothes, their slightly more-dishevelled-than-usual hairdos (which

almost seem to mimick the color of the foliage), and the distant looks on

their faces (only John looks at you directly, with more self-assured

condescension than ever before). And then, of course, there is the

distended-distorted effect on the finished photo, which came about more or

less by accident and has regularly been interpreted as a symbolic

announcement for the coming of the LSD era. Were we a subspecies of Sherlock

Holmes, we would probably have to conclude that the music within the album must reflect the influence of folk

music (the foliage), angry garage rock (the informal looks and the semi-sneer

on John’s face), and chemical substances (the distortion and the «globulous» lettering by Charles Front which would soon

become the default font for all things psychedelic) — and we’d be right on

all three counts, even if it’s all retrospective cheating.

Then there’s the album title,

which was chosen, I guess, just because the guys wanted their LP titles to

start having an identity of their own, and the pun «rubber sole» – «rubber

soul» seemed to possess precisely that kind of identity. The Beatles

themselves explained the idea of rubber

soul as a punny variation on plastic

soul, as if this was some kind of self-humiliating homage to American

soul artists, but, honestly, such a move would have made far better sense for

bands like The Spencer Davis Group or Manfred Mann, whose frontmen (Stevie

Winwood, Paul Jones) took far more pride in imitating black American soulmen

than John Lennon or Paul McCartney. While a little bit of Motown influence

certainly has its place on Rubber Soul,

as it had on about 99% of records by British pop artists at the time, Rubber Soul does not really have a

single song per se that would qualify as «soul music», treading the same

ground with the likes of Otis Redding or Marvin Gaye. Rather, it’s just a

title that marks a short-lived «pretentious age» in the titling of Beatles’

albums, together with Revolver; by

1967, the band would be completely over that phase. But in 1965, it served

its purpose — dispensing one more drop of intriguing mystery for the adoring

fanboy or fangirl, ready to be guided further into the unknown.

In the absolute majority of

Beatles narratives, a thick red line is always drawn between Rubber Soul and everything that

preceded it — this, the way we are

usually taught, is where the Beatles effectively ceased to be a

teenager-oriented pop band and transitioned into their mature,

psychologically deep, and musically experimental phase; a message that

sometimes has the negative collateral effect of having Beatle neophytes

ignore everything that came before and starting their musical journey with

the Beatles either with this record or with Revolver. Big mistake, unless you’re in a real hurry and unable

to devote just a few more hours of your precious time to one of the greatest

musical acts of the 20th century. Big mistake also because the Beatles’

musical evolution was precisely that — evolution,

gradually taking place in small (or big) steps from one LP to another, rather

than revolution with a clear and

indisputable line of demarcation. Some of the songs on Rubber Soul had a more traditional feel and could have easily fit

in on Help!; others were already

ahead of their time and could have felt perfectly appropriate on Revolver or even Sgt. Pepper. But although the same could probably be said of just

about any Beatles record, since they all combined nods to the past with peeks

into the future, I do believe that there are two facts about Rubber Soul that make it into the «quintessential transitional record»

for the band.

Fact #1: this is the first ever

Beatles record to feature original compositions that are not, in fact, «love

songs». Prior to Rubber Soul,

somewhat ironically, the only Beatles’ recordings to not feature love-themed

lyrics were their covers — stuff from rock’n’roll anthems like ‘Roll Over

Beethoven’ to jokey country tunes like ‘Act Naturally’. Even when John began

displaying signs of Bob Dylan’s influence, compositions like ‘I’m A Loser’ or

‘Help!’ would still formally remain

songs about the protagonist’s relationship with his precious other; it’s

almost as if they were aching to break out of the formula but were still

being kept back by either social pressure or, more likely, shyness and fear

of embarrassing themselves through lack of experience with poetic language. Rubber Soul finally breaks through

that barrier — still tentatively, for sure, but with all of the band’s songwriters expressly trying their hand at

stuff that goes beyond the boy-meets-girl or boy-loses-girl motives: John

with ‘Nowhere Man’, George with ‘Think For Yourself’ and even Paul with

‘Drive My Car’ (which could, I suppose, technically be described in

boy-meets-girl terms, but they’re not even in a relationship!). Plus, of

course, there is John’s stuff such as ‘Norwegian Wood’ or ‘In My Life’, which

is about romantic relationships,

but described from such completely new and unexpected angles that neither

could really be classified as a «love ballad». If anything, this is a heck of

an objective marker that demands a thick red line. BUT...

Fact #2: this is the last ever Beatles LP to feature songs

that were actually played live on stage for the band’s regular tours, though

the meager two selections were quite telling: George’s ‘If I Needed Someone’,

which he may have been regarding as his finest composition to date (and

gladly sang it in concert over his previously being limited to covers like

‘Roll Over Beethoven’ or ‘Everybody’s Trying To Be My Baby’), and John’s

‘Nowhere Man’, which, consequently, earns the honor of being one of only two

non-cover non-love songs performed live by the Beatles in their touring era —

the other being ‘Paperback Writer’. Still, this does mean that the music on Rubber Soul still fell into the «technically

performable» category, as opposed to Revolver, which came out in August 1966

but whose material was never even rehearsed for the band’s last North

American tour of the same month. And, indeed, you can easily close your eyes

and visualize the Beatles singing most of Rubber Soul on stage in 1965–1966 — but good luck trying to

imagine the same with songs like ‘Eleanor Rigby’, ‘She Said She Said’, or,

most jawbreakingly, ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’.

In between these two observations

lies everything else: Rubber Soul

is an album of contrasts, and also one where the four distinct personalities

of the individual Beatles — yes, even Ringo — get delineated more clearly

than ever before while still allowing for some collective spirit to show

through (not to mention continuous minor mutual influences enriching the

individual contributions in ways that would be forever closed off after 1970,

despite all the talent still being there). And then there’s all those other influences, too: with Dylan

being the proverbial idol of 1964, 1965 finds the group paying more close

attention to the contemporary American scene on the whole, starting with the

new developments in pop and soul music of the African-American variety

(Atlantic to Motown) and ending with the newly nascent folk-rock of The Byrds

and their own followers across the Atlantic.

But let us start from the

beginning. It’s been quite a long time since a Beatles’ LP opened with a Paul

song rather than a John song — and, for that matter, since it opened with a

distinctive electric guitar line rather than a bombastic vocal hook ("it won’t be long yeah...", "it’s been a hard day’s night...",

"this happened once before...",

and, of course, "HELP!").

This is hardly just an accident: Rubber

Soul had very few songs written for it that could qualify as all-out

«rockers», but the Beatles had been accustomed to the practice of beginning

and ending their LPs with blasts of energy, so it was probably a toss here

between ‘Drive My Car’ and ‘Run For Your Life’, and, well, the latter song

must have been way too nasty-sounding to provide the necessary opening

positive blast...

...not that the opening blast is

perfectly well described as «positive», though. The prevailing mood in ‘Drive

My Car’ is that of sarcasm, and sarcasm was generally not a thing associated

with the Beatles, and definitely

not with Paul McCartney. John, of course, was well known for sarcasm in his

everyday behavior, both onstage and off it, as well as in his non-musical

writings — but up to this point, he was very careful about sowing any

sarcastic seeds in his songs; and Paul was about as sarcastic as the average

folk singer in Greenwich Village. ‘Drive My Car’, however, does not merely

feature lyrics that roast pretentiously inadequate socialites to almost the

same crisp as Mick Jagger or Ray Davies; it even starts out by adopting the

meanest guitar tone as of yet heard on a Beatles song. It’s a fuzz effect

alright, but George did not use the same kind of overwhelming, deep-and-dirty

fuzz as had already been popularized by the Stones with ‘Satisfaction’ (even

if, I believe, George and Keith used the exact same pedal); it’s a lighter, more

playful version, which perfectly well complements the «light-hearted mockery»

of the lyrics.

Apparently Paul went on record

saying that ‘drive my car’ was an old blues euphemism for sex or something

like that, but I have been unable to find direct confirmation of this; I suppose that he may have been thinking

of something like Memphis Minnie’s ‘Me And My Chauffeur’ ("won’t you be my chauffeur, I wants him to

drive me downtown") which is definitely about sex — for that matter,

reverting us to the etymological identity of the word chauffeur = ‘warmer-up’ — but I am not even certain that the

analogy truly popped up into Paul’s or John’s head when they were

collaborating on those lyrics. (Another urban legend, apparently kindled by

the 2014 TV series Cilla, is that

the song tangentially refers to Cilla Black who made her manager and future

husband Bobby Willis turn down his own recording contract because she needed

him to "drive her car" — which is far more close to the song’s

message, but could be just a puffed-up tale).

In any case, there is no need to look for any sexual metaphors

in ‘Drive My Car’ unless your stated goal in life is to find sexual metaphors

in everything. There is, however, a need to look at ‘Drive My Car’ as the

Beatles’ first tongue-in-cheek look at themselves from the «stardom» angle —

this is a song that they could hardly have been able to write even a year

earlier, reflecting a somewhat jaded air that could only have come from a

long period of moving up the social ladder. And most importantly, this air is

coming from Paul, not John. The

world might not have realized that immediately, but ‘Drive My Car’ announced

the arrival of a new Paul McCartney — the eccentric, whimsical,

try-anything-once Paul McCartney who would very soon become the primary

energy-generating engine for the Beatles in their «mature» stage. For the

sake of historical correctness, too, it should be noted that Paul’s original

lyrics for the song ("you can buy

me diamond rings") were said to be traditionally fluffy, and it took

a solid session with John at his side to arrive at the sarcastic wit of the

final version. But the final version was

fully endorsed by Paul, and there is no doubt that his own lyric-writing

skills must have been greatly expanded by the successful result.

And it doesn’t hurt, either, that

this «new Paul arrival» would be presented in the form of one of the band’s

most musically and sonically sophisticated songs to date. A change in

artistic philosophy always goes better with a little revolution in musical

style, doesn’t it? There is usually said to be a strong Stax influence here,

with McCartney’s bass and Harrison’s guitar joining together in low-end

unison, but this is still a pop-rocker with sharply pronounced, repetitive,

tightly disciplined vocal and instrumental hooks, rather than the

comparatively more loose and free-flowing melodies by the likes of Otis

Redding. The song has grit and determination as it ploughs on (more cowbell!),

not to mention Paul’s slide solo which, as it climbs higher and higher up the

scale in those final bars, has almost more of an Indian feel to it than the

actual use of the sitar on ‘Norwegian Wood’ further on down the line. And let

us not forget about how brilliantly the sarcastic mantra of beep beep-mm, beep beep yeah! «modernizes»

the jam-coda repetitive endings of the past by bringing them in line with

this new ironic attitude. She’s got no car, and it’s breaking her heart, but

who’s to stop her from honking?

Another thing that is quite

striking about ‘Drive My Car’ is the increased level of «textural» diversity

and richness. Before 1965, the Beatles were always mostly concerned about basic instrumental melody and vocal

harmony, which usually meant that you could more or less extrapolate the

first 30–40 seconds of any Beatles song onto the rest of it, predicting

everything but the instrumental break. Likewise, instruments beyond the

standard rhythm-lead-bass-drums combo were rare (at most, a piano part here

and there). Listen to a bombastic album opener like ‘A Hard Day’s Night’ or

‘Help!’ for the first time in your life and chances are your attention won’t

even be drawn to anything other than the vocal melodies which just get you

immediately entangled in that unstoppable tide. ‘Drive My Car’, while

certainly not the most inventive Beatles song when it comes to build-up (the

sonic arrangement is kept fairly stable throughout), is really the band’s first album-opener which explicitly states

that "we’re not the boy band

you’re looking for — we are the music makers". I myself remember

fiddling with the stereo balance on my old cassette tape player and how

‘Drive My Car’ was so particularly striking when you muted either the left or

the right speaker: vocals only and percussion in one channel, and then you

could just get the guitars and pianos in the other and it was a completely

different and still awesome experience.

But let’s

get back to this «new and improved Paul» thing. ‘Drive My Car’ is clearly the

most radical stage of his evolution on here, even if it is unquestionably

tainted with John’s DNA as well. But although the other three songs on here

which are also direct brainchilds of Paul’s — ‘You Won’t See Me’, ‘I’m

Looking Through You’, and ‘Michelle’ — are more conventional in their subject

matters, they all reflect significant advances in lyrical skills and

emotional complexity. That line about how "I have had enough, so act your age" in ‘You Won’t See Me’

might just as well be hurled by Paul at himself, as he struggles, and

occasionally succeeds, in overcoming standard romantic clichés.

Doubtless, the difficulties of his relationship with Jane Asher contributed

to this, as both ‘You Won’t See Me’ and ‘I’m Looking Through You’ are usually

said to have been written about their confrontations; and although neither of

the two can raise above the «male point of view», as the protagonist always

keeps presenting himself and only himself as the wronged side, it’s still a

far more interesting point of view than, say, the straightforwardly

unreflected "I ain’t no fool and I

don’t take what I don’t want" bit from ‘Another Girl’.

‘You Won’t

See Me’, in particular, has always seemed like a heavily underrated classic

to me — just because the song does not have something glaringly unusual and

outstanding about it, like that accordeon in ‘Michelle’, does not warrant

popular neglect. Have you ever noticed that, despite being always branded as

the sentimental Beatle, Paul McCartney is pretty much incapable of presenting

himself, in any of his songs, as the owner of a broken heart? Even John

Lennon could find it in his heart to plead and grovel; meanwhile, Paul’s

«women problems» always result in anger, bitterness, and accusations. ‘You

Won’t See Me’ is a perfect example — the lyrical hero here is confused and

embittered about his lover not returning his calls, but all those "I will lose my mind if you won’t see me"

and "I just can’t go on"

sound like expressions of discomfort rather than desperation. The song has a

sharp, stern, driving pulse, punctuated by Harrison’s choppy, blues-rockish

rhythm chords and extremely well-disciplined, which would never agree with a

message of madness and chaos — it’s more of a complaint about the ungrateful

girl wasting the protagonist’s precious time with her irrational behavior.

Yet at the same time there is a heavy cloud of psychological confusion

hanging around the song, illustrated first by the nagging, sustained backing

vocals with their shifting pitch, and then, only during the last verse, with that totally genius move of

having Mal Evans holding down a single A note on the Hammond organ through

all of its bars. Ever since I was a little kid listening to this on tape, I

always wondered about why that last verse sounded deeper and heavier than

everything that came before it, as if some new dimension formed itself around

the singer — and as I found out decades later, it was all just a member of

one not-particularly-musical roadie holding down one note with his finger. It

may arguably be the quintessential example of generating genius effect with

the simplest means in pop music history.

‘I’m

Looking Through You’, thematically, is pretty much the sequel to ‘You Won’t

See Me’: the hero and his partner are reconnected, but things don’t get much

better because some invisible line has already been crossed. This time,

McCartney chooses the language of the young folk-rock genre to deliver the

message — which is perfectly appropriate, given how both Bob Dylan and the

Byrds had already used it to deliver series of sharp barbs in the general

direction of their real or virtual girlfriends. It’s a bit slight / clunky next

to ‘You Won’t See Me’, both lyrically and musically ("the only difference is you’re down there

/ I’m looking through you, and you’re

nowhere" has always confused me with its unintentionally

Schrödinger’s perspective), but what makes it more fun is when you

compare the original version (as seen on bootlegs or Anthology 2) with the finalized one. Originally, each verse ended

with a short instrumental chorus playing nasty, distorted two-note organ

«strikes» that would temporarily transpose the song to a gritty blues-rock

setting, as if to symbolize the protagonist temporarily going off his rocker

and winding himself up to a state of hyper-aggression. "Don’t make me nervous, I’m holding a

baseball bat", that kind of vibe. But in the end, they threw out

that idea — the Hammond chords stay there all right, but now they are not as

shrill or distorted, and the main hook power is transferred to the little

winding «jiggy» riff played by George, which is far more playful and cuddly

than crazy-angry. I still couldn’t call that mood shift perfect — I mean, who

on earth breaks out into a harmless jig upon prodding himself into an

emotional outburst? — but I appreciate the effort in recognizing that a

particular transition was unnaturally jarring and trying to remedy it to the

best of their ability. Still, I believe that ‘I’m Looking Through You’ falls

a wee bit short of the Beatles’ standard for perfection, and could have used

a little more thought in all departments.

The same

complaint is, of course, inapplicable to ‘Michelle’, which is as perfect as a

song of that kind could ever be, but writing about ‘Michelle’ after all these

years feels particularly embarrassing, what with all of its

«Frenchploitation» resulting in its status as one of those several «Beatle

songs for ringtone people», along with ‘Yesterday’, discussing which in a

serious tone is akin to discussing ‘Jingle Bells’ or ‘Happy Birthday’ in a

serious tone. I shall be, therefore, very brief on this one, and just state

two fairly obvious observations that might, perhaps, help broaden somebody’s

perspective on this one: (a) the «Frenchploitation» is forgivable because of

its absolute innocence — this is clearly

written from the viewpoint of a humble admirer of a non-understandable,

mystical foreign beauty, mesmerized by the very fact of the communication

breakdown and probably not wanting at all to improve his understanding of the

French language or culture so as not to break the spell; (b) the fact that

the base melody of the song actually owes more to Chet Atkins than Michel

Legrand or Marguerite Monnot is quite hilarious in itself, since it

reinforces the idea of «American tourist lost in the shadow of the Eiffel

Tower», with a clever lad from Liverpool serving as a medium.

In any

case, cheesy or not, ‘Michelle’ is the final top cherry on Paul McCartney’s

triumph of diversity here: Stax, Motown, Byrds, Chet Atkins, and the Eiffel

Tower are all run through his melodic converter and emerge transformed and

reinvented in different ways. This is not «peak McCartney» yet; he has not

yet properly begun to create his legendary «gallery of characters», singing

mostly from his own perspective, which, as we know, is not really the easiest

thing for him to do —probably the biggest difference between him and John, as

John always found it difficult and, perhaps, even deeply dishonest to hide

behind a mask, whereas Paul would turn out to be one of the biggest mask fans

in the musical world. But it also makes this little transitional batch of

songs somewhat unique, as we see Paul move away from stereotypical and

formulaic ways of songwriting (especially in terms of lyrics) to something

more deeply meaningful, trying on the cloak of «singer-songwriter» for a

short while. It did not suit him all that well, so he would eventually

exchange it for the much better fitting cloak of «master storyteller». But

it’s fun to catch somebody in a moment of such a transition, is it not?..

Meanwhile,

for Beatle John this transition seems to have been completed. Out of the five

«totally John» contributions to Rubber

Soul (‘The Word’ and ‘Wait’ are «mostly John», but reflect more of a

collective group spirit than the others), only the much-maligned ‘Run For

Your Life’ — which, since it closes the album, we shall return to later —

reflects the past rather than the future. Any

of the other four songs could have easily and comfortably fit onto any of the

later Beatles albums, or even onto some of John’s own solo records: apart

from a leftover naïve or clumsy lyrical twist every now and then, they

all capture John Lennon at the peak of his creative abilities.

As I

already said, the key difference in the evolutionary arcs of John and Paul

was that Paul, through much of his life, strived to become an actor, trying on one persona after

another; be it Sergeant Pepper or the traveling con man in his video for ‘Say

Say Say’ with Michael Jakson, Paul loves feeling what it is to be in somebody

else’s skin. John’s journey was the complete opposite — early on,

inexperience forced him to adopt other people’s clichés and formulas,

but by late 1965, he was all but set to follow the principle that would soon

be put into words by Elvis: I’m never

going to sing another song I don’t believe in. Elvis himself,

unfortunately, did not succeed in keeping that vow (or maybe he thought he

did, but it didn’t help him anyway), but for John, this would become the

natural way of existing, as he’d hatefully blast to pieces everything that he

perceived as «fake» (e.g. ‘It’s Only Love’ from Help!).

Perhaps it

was this particular fork in the road, more than anything else, that

ultimately led to the Beatles’ breakup (and a somewhat similar dichotomy would

occasionally strain the partnership of Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, though

their own personalities were better capable of weathering any such storms) —

but as of late 1965, I suppose that John and Paul were still incapable of

coming up with the well-thought-out conclusion that they were really

incompatible with each other, and with Paul writing these Asher-inspired

songs like ‘You Won’t See Me’ and ‘I’m Looking Through You’, and with John

learning to write direct songs about his own state of mind, Rubber Soul might ultimately be the

most «personal» LP the Beatles ever released — everything that came later was

very much torn between the personal and the impersonating.

Technically,

one could probably perceive a song like ‘Nowhere Man’ more «impersonating»

than «personal», especially if you happened to see Yellow Submarine as a little kid and your memory forever

associated ‘Nowhere Man’ with the character of «Jeremy Hillary Boob, Ph. D»

from the cartoon. It is, by the way, somewhat telling that the earliest

Beatles song on Yellow Submarine —

the pinnacle of the Beatles’ «psychedelic» image — is ‘Nowhere Man’ from Rubber Soul, as if it was

specifically intended to point out that the band’s psychedelic period starts here. But it somewhat depends also on

how far-stretched our limits are for the term «psychedelic» itself. For

instance, are ‘Nowhere Man’ and ‘Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds’ both

psychedelic, or is the latter more psychedelic than the former? ‘Lucy In The

Sky’ does, in fact, create an alternate imaginary colorful reality; ‘Nowhere

Man’, on the contrary, is very much a tale of this world, merely stripped of its everyday hustle-and-bustle.

And oh

yes, bless you, writer’s block, as the tale goes that John created ‘Nowhere

Man’ while lying on the studio floor and desperately realizing that he had no

new ideas to use for writing another number — which led him to the idea of

writing a song about nothing, and make that proper nothing, rather than the famous «pseudo-nothing» of the

creators of Seinfeld. The very

first Beatles song that is not — or, at least, has no hope of being

interpreted as — a love / romance song, ‘Nowhere Man’ is also the first in a

series of John tunes that could be collectively dubbed «cosmic flow songs»,

which also includes ‘I’m Only Sleeping’, ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’, ‘Across The

Universe’, ‘#9 Dream’ from his solo career, and perhaps a couple other songs

with the overall message of turn off

your mind, relax and float downstream. It is a classic Taoist / Buddhist

motif that you would rather expect from the likes of the ultra-religious

George Harrison — but, surprisingly, George never wrote a single song like

that in his lifetime; despite the «quiet Beatle» reputation and all, his

spiritual songs would always be bursting with activity, philosophy,

preaching, and emotion. He had absolutely nothing on John when it came to

truly becoming «one with the flow» — even a song like ‘The Inner Light’,

directly quoting the Dao de jing

and all, feels like an energized travelogue next to the titles I just listed.

The actual

genius of ‘Nowhere Man’, though, is how it manages to convey this «cosmic

flow» feel within what seems like a relatively conventional and fairly

dynamic folk-rock framework. There’s no sitar here, no droning, no super-slow

tempo, you can even dance along to the tune — heck, the Beatles actually took

this on tour with them in 1966

rather than ‘Drive My Car’ or ‘What Goes On’ — but it does feel like the

perfect song for lying on the floor and floating downstream, doesn’t it?

Perhaps it has something to do with the opening a cappella vocal harmonies — he’s a real Nowhere Man, sitting in his

Nowhere Land — giving the impression of a lullaby, even if they are

delivered with much more energy than any genuine lullaby. The steady, lulling

tempo, the soft change to the relative minor key in the bridge which gives

the impression of added depth without disrupting the flow, the mantraic

repetition of making all his nowhere

plans for nobody at the end — this is really the perfect meaningful

lullaby for an infant, even if it was actually written about a 25-year old

Scouse git. But I guess he was

lying in a fetal position, more or less.

One thing

that separates ‘Nowhere Man’ from all those other cosmic flow songs, though — and ultimately makes it more of a

fascinating puzzle than all of them — is that the others all sound like works

of professional advertisement, a set of alluring, tempting invitations to

drop everything and go chasing after all that limitless undying love which shines around me like a million suns

and so on. ‘Nowhere Man’, however, does not at all feel like shameless

propaganda for the song’s portagonist or his personal world of anti-matter.

First, John cleverly shifts the narrative to 3rd person perspective, as if he

is really the exhibit and we are trying to give him an objective assessment

from the other side of the bars. Second, there is no morale here, no

judgement, no admiration or condemnation, perhaps just a sort of slight

bewilderment and amusement. We are teetering on the brink that separates our reality from his, getting a good view and soaking in the fumes while at the

same time remaining somewhat aloof and skeptical. Our own reaction ranges

from a subtle desire to help ("you

don’t know what you’re missing... the world is at your command") to

an equally subtle desire to let things evolve precisely the way they are

meant to be ("leave it all till

somebody else lends you a hand"). At the end of the day, the

question of whether it is awesome or awful to be a Nowhere Man remains unanswered.

Heck, I don’t believe it even remains asked.

As is

common for all the best Beatles songs that have to include at least one or

two «sonic puzzles», ‘Nowhere Man’ also has its own befuddling moment: the

guitar solo, which was apparently played in unison by John and George on twin

Fender Stratocasters, ends with this one high harmonic note — the «lightbulb PING!», I call it — which is

absolutely not required, as the solo melody has already been resolved before,

but still adds a terrific final counterpoint. Usually a sound like that would

symbolize intellectual or spiritual illumination — the lightbulb, right? —

and you could, in fact, see this as a symbolic recognition that it is

precisely the «Nowhere Man Lifestyle» that ultimately leads to the Perfect

Awakening. But on the other hand, it is not at the end of the song, it’s in

the middle, so perhaps it is more like an imaginary scenario: what could and should be, a model, a blueprint, whereas the actual reality is

far more ambiguous and uncertain. In any case, it is certainly one of the

most intriguing single-note moments ever generated by George Harrison. (He

could never properly recreate it in any of the live performances of the song

I’ve heard, though. Touring really sucks!)

Yet at

this point in Beatles history, ‘Nowhere Man’ is still more of an accident, a

result of spontaneous illumination pointing the way (one way?) to the future;

when it comes to writing on schedule, John Lennon is still mainly preoccupied

with writing about boy-girl relationships. He does continue to write about

them in more and more adventurous ways, though, and if your acquaintance with

Rubber Soul had been limited to

the first two songs — ‘Drive My Car’ and ‘Norwegian Wood’ — you would have

left with a firm conviction that the romantic Beatles had all but

fundamentally merged with the venomous Rolling Stones, with a small but

palpable blister of Bob Dylan in between.

Melodically,

‘Norwegian Wood’ picks up right from where ‘You’ve Got To Hide Your Love

Away’ left off on the previous album: a slow, shuffling, meandering acoustic

ballad with a mumbling, morose Lennon vocal. And once again, the hero of the

song becomes the victim of female cruelty — except that this time, he prefers

to take retributive action rather than just stand "head in hand"

and whine like a lil’ pansy. That first verse – "I once had a girl, or should I say, she once had me" —

already builds more character by itself than an entire poem; a little folk

spirit, a little Dylan, and a little sarcasm. As the story unwraps before our

eyes — and this is the first actual story

told within a Beatles song — we get a visual image of the posh, pretentious,

probably esoterically-minded lady (according to McCartney, «Norwegian wood»

was what the furniture was made of in the Ashers’ house, unless he’s just

trying to score himself extra credit for the words here) who is clearly

willing to show off but not so eager to put out, and in the end, receives her

just desserts, so to speak. Funny enough, discussions about the literal-figurative

meaning of ‘Norwegian Wood’ still shake up the Internet from time to time,

and plenty of people still refuse

to take the song’s shocking conclusion of I

lit a fire literally: how could

sweet baby John have written a song about setting somebody’s house on fire,

especially if it was just for the «crime» of having to sleep in that

somebody’s bathtub? But these are probably the same people who think that

Phil Collins actually declined to save a man from drowning, because, well, it

says so in the song.

To me,

much more interesting is a thematic link between ‘Norwegian Wood’ and the

significantly earlier ‘Play With Fire’ — while the Stones’ tale of the

crime-and-punishment of their imaginary Posh Girl model is more abstract, the

basic message remains the same: "don’t

you play with me, ’cause you play with fire" (and also delivered

within the setting of a slow acoustic ballad, though the Stones go for a

spooky Gothic vibe rather than Greenwich Village-style folk). John himself

stated that ‘Norwegian Wood’ was his attempt to write a «veiled» account of

an affair he had so as not to rile up Cynthia, but in the end the song is not about an affair — it’s about a failed stab at an affair and its

rather out-of-hand consequences. Thematically, it belongs to that long, long

series of songs written by young British and American pop stars about the

inevitable problem of «low-middle class boy winds up in high society, picks

up upper-middle class girl, sit back and watch the show». The Stones, in

particular, loved that genre, but apparently the Beatles were not immune to

it, either. Moral of the story: «if

your girl invites you to sit on a rug instead of a chair, you clearly took a

wrong turn in life somewhere».

That the

song once again employs a Dylanesque melody to get that message across is no

accident — given Bob’s own story of putting down beautiful (and rich?) girls,

John finally got brave enough to deliver his own take on that paradigm. That

it also becomes the very first pop song to use a sitar for its arrangement is,

however, more of an accident. Well, after all, it is documented to have more or less been an accident, with George

just happening to pick up the instrument that had lied there unused for some

time, and the melody he plays is quite trivial, too (this was before he

actually started taking lessons on the instrument). And you can easily

picture ‘Norwegian Wood’ without the sitar and it’ll still sound good with

just the 12-string guitar. (There’s an earlier version on Anthology 2 where the sitar is also

played during the bridge section and it is absolutely-utterly-unbearably

godawful there, thank God somebody had the bright idea to exclude it).

But there

are two good «artistic» arguments for why, in the end, it does belong: (a) the simple one — an

«Indian vibe» would definitely agree with the interior of an

exotically-arranged posh house with rugs instead of chairs, symbolizing the

potential Orientalistic trendiness of John’s femme fatale; and (b) the more complex one — the sitar, an

instrument that (to the occasional Western mind at least) symbolizes

peacefulness and wisdom, somehow reinforces the «cool, calm, collected»

attitude of the protagonist, who allows himself to be quietly manipulated

without displaying any emotional excesses, and then, eventually, just lits

his little fire without any particular turmoil and to little fanfare. Listen

to how unperturbed and gentle this gentleman remains throughout — a far cry

from the usually over-emotional vocal deliveries that most of John’s songs

were known for previously. In the end, ‘Norwegian Wood’ is a combination of

gentle, funny, and shocking that remains fairly unique in the Beatles’

catalog, and is perhaps their most sophisticated twisting of the Dylan

influence (Bob’s own ‘4th Time Around’ has often been called a conscious

answer to ‘Norwegian Wood’, or even a «parody» of it, though I really don’t

like that word in this context; I feel, though, that there are still far more

differences between the two songs than similarities, though their comparison

always makes for a good intellectual challenge).

But

‘Norwegian Wood’ is also a fantasy — the product of John’s creepy

imagination, a grotesque and terrible scenario of hyperbolic revenge from a

"what-if..." perspective. Meanwhile, a song like ‘Girl’ feels like

it should hit much closer to home. John starts it up with the same kind of

«folksy» introduction, or maybe even in a slightly more epic key — "is there anybody going to listen to my

story..." is almost Homeric here — but this time, the song does not

have a proper plot and is instead a character portrayal, John’s most direct

and detailed one to date, so much so that it is difficult to believe he is

not talking about a real person, or at least about somebody directly inspired

by a real person. In subsequent interviews, John himself would insist that

the «girl» was an imaginary character, a phantom vision presaging the arrival

of Yoko — but I have a nagging suspicion that he was confused, because the

portrait by no means agrees with what we know of the John and Yoko love story

("she’s the kind of girl that puts

you down when friends are there?" "was she told when she was young that pain would lead to pleasure?"

— nah, come on!).

It seems

much more likely to me that in reality, the song was inspired by John’s

concurrently troubled marriage with Cynthia — the only «girl» with whom he’d

had a lengthy enough relationship by that time to use as a basis for such a

song — but sufficiently well masked so as not to be easily guessed. The

romance here, while clearly managing to hold together for a while through

sheer mystical infatuation, is ultimately doomed, with zero chance of a happy

ending, so a real flesh-and-blood Cynthia would certainly fit the bill much

better than an imaginary Yoko. But it does not matter so much, of course, if

‘Girl’ has a real flesh-and-blood prototype, as it does that a song like

‘Girl’ would have been impossible to write, or to sing with such feeling even

a year earlier — its painful, tired trod, loosely based on a Greek melody

(Paul usually mentions Mikis Theodorakis’ soundtrack to Zorba The Greek as an inspiration), is the confessional sound of

somebody who’s lived through a long period of experience, and one that goes

beyond the simplistic «she cheats on me, I cheat on her, we’re probably

through but it still hurts» messages of generic breakup songs. John is a

master of many emotional states, but there are few he is capable of

transmitting better than basic tiredness

— exhaustion, fatigue, prostration, feeling drained and worn-out, you name it

— and ‘Girl’ is the song that opens up that kind of shop, but, naturally, it

should have taken at least a few years to get around to that state of

conscience.

The base

message of the song is even better encapsuled in its chorus, I think, than in

the (already quite superior) lyrics. How many one-word choruses do we know

that simultaneously reflect adoration, misery, and recrimination? but this is

precisely what John’s "girl...

girl..." does, torn between the very ‘pain’ and ‘pleasure’ that are

explicitly mentioned in the last verse, with the sharply hissing breath

intake (John gave specific instructions to George Martin to capture that one

as clear as possible) as a particular point of interest. There are really

only two types of situations in real life, I think, when you make that kind

of sound — (a) during sex, and (b) before taking some deep and brave plunge

into the unknown (sometimes both are the same thing). That’s ‘Girl’ for you,

the conflict between erotic infatuation and intellectual disillusionment.

(Pretty sure that was more or less the story of John’s relationship with

Cynthia). It’s a nasty business, of course, because, just like in everything

he wrote at the time, the blame is always on the girl, never on the guy, who

comes across as a helpless, pitiful victim (which can hardly be true about

John at the time). We only get one side of the coin here, and have to use our

own intellect and imagination to guess what might be on the other side. But

damn if this one side of the coin isn’t a real beauty in all of its

psychological turmoil. And damn if that last verse — "did she understand it when they said that

a man must break his back to earn his day of leisure?" — isn’t a

phenomenally well-modernized take on the old and beaten "I worked five long years for that woman"

motif.

But as

cool as those lyrics are, neither ‘Norwegian Wood’ nor ‘Girl’ represent the

pinnacle of John’s new-and-improved verbal skills on this album; that honor

squarely falls to ‘In My Life’. Not because ‘In My Life’ has any particularly

mind-blowing twists of phrase, similes, metaphors, or allegories; on the

contrary, out of all these songs it is probably the most direct and

unambiguous — you do not have to reconstruct vague particularities of the

plot, like in ‘Norwegian Wood’, or make guesses about the specific details of

the protagonist’s feelings, as in ‘Girl’. It is simply that ‘In My Life’ has

a narrative that confounds our expectations. We are used to the Beatles

singing love songs, so when John begins singing a seemingly nostalgic ode to

"all these places" that

"had their moments", we

are confused — it’s as if he’s turning into Frank Sinatra here, giving us his

own take on ‘It Was A Very Good Year’ (which, by the way, might not be a

total coincidence: Sinatra’s September

Of My Years had just been released in August ’65 before the Beatles went

into the studio to record Rubber Soul,

and must have caught John’s attention one way or another). A heartfelt

nostalgic anthem from the 25-year old John Lennon? Talk about premature

maturity, but then again, why the hell not? Especially considering the sheer

distance they all crossed from their past lives to their present ones in a

matter of three years — certainly their existence in pre-1963 Liverpool must

have seemed like a total dream to the Fab Four by this point.

But then

in the second verse, the song completely shifts gears: "But of all these friends and lovers /

There is no one [who] compares with you...". So it is not a nostalgic song after all — the

nostalgia was just lyrical bait for us to get to the real message of the

composition. This is John renouncing

his past, not yearning for it, and looking into the future. I’m no big expert

on the art of popular songwriting, but I did sit through of Ella Fitzgerald’s

Songbooks at one time, and I am

not sure that this kind of smooth transformation, from old-time nostalgia to

current infatuation, had ever been properly realized by any of the great

lyricists of the 20th century. If John himself is to be believed, the song

started life as a pure nostalgia

trip — with lyrics actually referencing Strawberry Fields and Penny Lane in

one of those «premature» efforts — but then he didn’t like the results and

reworked them into this shape,

connecting and contrasting the past with the present and using the nostalgia

as merely a trampoline rather than a goal-in-itself. How grand is that?

And

speaking of trampolines, this

particular "in my life, I’ll love

you more" is most definitely not

about Cynthia Lennon, who, for all we know, actually belongs in the category

of "lovers and friends I still can

recall", despite still being very much a part of John’s life in

1965. If anything, it is not ‘Girl’, but rather ‘In My Life’ that presages

the arrival of Yoko — that one idealized romantic partner who can, on her

solitary own, overwrite and override all the happy memories of one’s past

life. Nobody could guess that in 1965, but ‘In My Life’ was indeed a prophecy

that John would become capable of realizing just a few years later — in fact

I’m sure he would have re-recorded it with a new dedication, if only his

personality happened to end up on the cheesier rather than classier side (but

it’s a pretty fantastic kind of if).

(On a

somewhat humorous note, looking over the lyrics of ‘In My Life’, I find that

it makes an absolutely perfect

cover for a Christian artist — I mean, from that kind of angle it’s almost as

if Saint frickin’ Paul himself wrote those words — and sure enough, there is

at least an acoustic cover by Phil Keaggy somewhere out there in the woods. Particularly humorous given how it

came out only a few months before John’s bigger-than-Jesus comments; I wonder

if he himself ever looked back on his final lyrical results and had such a

good laugh about what turns out to be his most Christian song ever.)

Of course,

we don’t just love ‘In My Life’ for its lyrics. We love it for its opening

tender riff, hanging out there suggestive and unresolved between each verse

until it finally gets a happy resolving «answer» in the final bar of the

song. We might love it for Ringo’s expressive drum pattern, where the hi-hat

acts more like the standard rhythm keeper while the bass and snare do their

steady melodic dance, giving the song its assured and energetic pace rather

than letting it go across all wishy-washy. We might be affected by how the

second part of the verse, so as not to let the song become too predictable

and lose our attention, is enlivened by the stop-and-start elements, as if

there is something so particularly

important about the line "all

these places had their moments" that we have to hear it without the

drums. We might appreciate the thin, ghostly backing vocals to the even

lines, haunting the lead vocalist like will-o’-wisps from the past. And, of

course, there’s always the George Martin-played solo, which, ironically,

probably did more to popularize the harpsichord for the upcoming

«baroque-pop» revolution than any other song of its epoch despite not being played on a harpsichord

(George played it slowly on a regular piano and then sped up the tape to

match the song’s tempo). A little faux-Bach is precisely what the doctor

ordered here, combining an «archaic» vibe to match the nostalgia theme with a

«church» vibe to match its rampant Christianity, uh, I mean, its general

romantic aura and all that.

In between

just these three songs, ‘Norwegian Wood’, ‘Girl’, and ‘In My Life’, we get a

huger emotional palette than we ever saw from John Lennon before — bitter

irony, straight emotional pain, and glorious cathartic premonition of the

future. Throw in the stark raving mad anger of ‘Run For Your Life’ (which I’m

still not ready to discuss yet), and there you have it, four basic emotional

states of which John Lennon would be the undisputed king in pop music — in my

personal opinion, not even until the breakup of the Beatles, but until his

last dying breath in 1980. And as far as I’m concerned, it is this incredible

ability to express those emotional states that makes all these songs so

great, much more so than any formally admirable musicological aspects. For

all the unusual elements in their chord sequences, harmonic arrangements, and

production details, their chief attraction lies in John’s vocal delivery;

take away every single instrument and those vocals alone, in all their

nakedness, would still be unforgettable.

In light

of these monsters, it is rather telling that two other songs whose authorship

also primarily lies with either John or Paul, but both of which radiate a

clear impression of «group work», feel somewhat slight in comparison to the

more «personal» stuff on the album. One of these is ‘Wait’, not a bad tune in

its own right, but one that I have always regarded as the weak link on Rubber Soul and shall probably

continue to do so until my dying day. Apparently ‘Wait’ was an outtake from

the Help! sessions, and oh boy

does it ever show. A catchy, but melodically rigid and lyrically generic

number, it is in the same structural ballpark with ‘Another Girl’ and ‘Tell

Me What You See’: verse, chorus, bridge, verse, chorus, bridge, no solos, no

interesting variations between the different verses, no proper build-up. On

its own, it’s okay, it’s a song about longing and yearning and it does have

some of that atmosphere. Inside Rubber

Soul, it is an official piece of filler, thrown in at the last moment so

that the album could get a Christmas release after all. If I were a sneaky

wizard, I would have justifiedly transposed it over to Side B of Help! and pinched one of its stronger

titles for Rubber Soul instead —

maybe even ‘Yesterday’, or at least ‘I’ve Just Seen A Face’. Then again,

perhaps it’s a good thing that ‘Wait’ ended up here, if only as a flashing

symbol of all the progress the Beatles had made in a matter of several

months.

Much

better, and much more suitable for the LP as a whole, is ‘The Word’, mainly a

John vehicle but feeling like a joint John-Paul declaration since so much of

the song is taken up by their twin harmonies in the chorus. Obviously, this

is a precursor to ‘All You Need Is Love’: the very first Beatles song on

which «love» is praised as a general concept, rather than used in the narrow

sense of being applied to a particular person. The lyrics are simplistic,

especially compared to all those great strides forward on John’s other songs,

but they are intentionally

simplistic: "in the beginning I

misunderstood", says John (and I assume that by beginning he really means middle

school, where indeed a simple mention of ‘love’ can easily ruin a boy’s

reputation), but then goes on to bravely admit "but now I’ve got it, the word is good" — well, I guess, being

a rich, talented, and admired superstar does

give you quite a bit of leeway after all.

This song, unlike ‘Wait’, I have

always loved as strongly as anything else on here, not because it promotes a

universal message of sunshine and marshmallows, but because it fuckin’ rocks. Play the first four seconds and

you will never guess that it is about a universal message of sunshine and

marshmallows. The opening piano chords are badass, the choppy, screechy

guitar licks are blues-rock incarnate, Paul’s bassline, when isolated, sounds like

a creepy theme from a spy movie, and the twin harmonies sound like a military

order as they drill themselves inside your skull (my favorite moment is the

transition to give the word a chance to

say, by which time the drilling has ascended to falsetto range and the

Jedi mind trick is pretty much complete). ‘All You Need Is Love’ is all

flowery and sentimental in comparison, but ‘The Word’ pulls no punches: it

spreads its message in the roughest, rowdiest way possible. Which is, of

course, why ‘All You Need Is Love’ became such a common staple of our

conscious, while ‘The Word’ remains a proverbial «deep cut» and is hardly

ever heard chanted across a sports arena. Nobody of note ever covered it,

either. (Well, Helen Merrill did back in 1970, and she even got the gist of

the vocals, but the arrangement was rather pathetic).

Granted,

‘The Word’ is by far the musically simplest number on the entire album, and perhaps it makes a big mistake by

alternating pathetically short verses with the lengthy and repetitive chorus.

But the chorus is supposed to be

somewhat mantra-like, which is no big deal if it’s such a musically kick-ass

mantra all the way. It’s pretty much throttling you with an iron grip:

"say the word, bitch! I dare you to say the word!" A

little more fuel in the fire and it would become parodic; even as it is, it

teeters on the brink of craziness. Of all the «anthem» songs in the Beatles’

catalog, it is the oddest.

Also,

while the track sequencing on the proper, un-mangled UK version of Rubber Soul is not yet nearly as

important as it would soon become, some of the stop-and-starts have an

accidental greatness of their own: ‘The Word’ reinforces the feel of

toughness, as its abrupt piano chords and guitar licks kick in a mere second

after your ears have been released from the punishment of Paul’s fuzz bass on

‘Think Yourself’ — that’s two songs in a row establishing rough spiritual

dominance, mercilessly kicking your ass before finally offering sweet

relaxating release with ‘Michelle’. Let us not forget that, despite all the traditional

«Beatles go folk-rock» labeling for Rubber

Soul, this was 1965, the year of fuzz, feedback, and emerging heroes of

heavy guitar such as Jeff Beck and Pete Townshend, and the Beatles wouldn’t

be the Beatles if they paid no attention to those new developments.

The fuzz

bass is what makes ‘Think For Yourself’, the first of George Harrison’s two

contributions to the LP, so distinctive, but it still has a fairly heavy

sound even without the fuzz bass part, as you can hear for yourself on the early non-overdubbed takes,

with just the regular bass part. Although the song has no bridge at all, it

more than makes up for it with the stark contrast between the verses, which

move at a slower, janglier, Byrds-ier pace, and the chorus, which picks up

speed, changes tonality, and almost takes us into a danceable blues-rock

sphere (the instrumental parts have quite a bit in common with ‘I Saw Her Standing

There’, amusingly). This is every bit as surprising and abrupt a shift as in ‘I’m

Looking Through You’, if not more so, making it the most musically adventurous

song George had written at that point.

But perhaps

the heaviest thing about the song are its lyrics. Prior to ‘Think For Yourself’,

all of George’s own compositions for the band — ‘Don’t Bother Me’, ‘I Need You’,

‘You Like Me Too Much’ — were in full agreement with the boy-and-girl

formula, even if ‘Don’t Bother Me’ felt rather distinctively bleak for a

simple song about relationships. ‘Think For Yourself’, however, is unusual in

that it leaves lots of space for interpretation. You can, if you so desire, picture it as a stern, stark admonishment

for a former romantic partner: George saying goodbye ("think for yourself, ’cause I won’t be

there with you") to a hopeless case of a lady obsessed with building

sand castles ("you’re telling all

those lies about the good things that we can have if we close our eyes")

and causing trouble and destruction with her reckless behavior ("I know your mind’s made up, you’re gonna

cause more misery"). In fact, I think that’s precisely the natural

way I’d looked at the song in my own early days. But then you read up on what

George himself had to say about it, and he says that it might actually have

been a diatribe against the UK government — again, makes sense, especially

given that he’d soon follow it up with ‘Taxman’ — and that’s a possibility,

too ("the future still looks good

and you’ve got time to rectify all the things that you should", isn’t

that right, eh, Mr. Wilson?).

One thing

is for certain: ‘Think For Yourself’, quite true to its title, marks a

turning point where George has begun to carve out a special niche for

himself, rather than just meekly trying to follow in his elder colleagues’

footsteps. The uncanny melodic structure, the unpredictable but natural flow

of chord changes, and, most importantly, the philosophical lyrics set him

here on a direct journey that would culminate in All Things Must Pass five years later. And unlike ‘Nowhere Man’,

which did come about more or less by accident, I think that George’s decision

to «make things more serious» was quite deliberately thought out, and not

merely inspired by that fateful visit to Indiacraft on Oxford Street during

which he bought the ‘Norwegian Wood’ sitar.

(On a side

note, I find it slightly adorable that a tiny excerpt of ‘Think For Yourself’

— the you’ve got time to rectify...

bit — was used by the writers of Yellow

Submarine in the scene where the Beatles use music to bring back to life

the Lord Mayor of Pepperland. It’s

like an implicit recognition of the importance of George Harrison’s

contribution to advancing the band’s music to a new stage. Come to think of

it, if performed in full, the song would have been almost as efficient as an

anti-Blue Meanies remedy as ‘All You Need Is Love’, but I guess they just

didn’t have the budget to realize the idea in full).

The

situation with George’s other song here, ‘If I Needed Someone’, is a bit more

ambiguous. Many people dismiss it, or at least treat it with a certain level

of condescension because it is such a blatant Byrds rip-off, nicking the riff

from ‘The Bells Of Rhymney’ with just a few minor adjustments to avoid a

copyright suit. (Ironically, pretty much the same chord sequence would also

be used by Pete Townshend for ‘So Sad About Us’ in a few months, but nobody

gave a damn because it was all buried so deep under Keith Moon’s drums, as

usual). I can join in the criticism inasmuch as I agree that the song is not

as «quintessentially George» as ‘Think For Yourself’, and that, along with ‘Wait’,

it is one of the few songs on Rubber Soul

that still somewhat reflects the spirit of the summer of 1965, rather than the autumn of 1965, in between which the tectonic plates of popular

music-making had so drastically rearranged.

I can also

join in the criticism inasmuch as I think the lyrics are a bit of a wasted

opportunity. The song starts out shockingly strong with its conditional

phrasing — "if I needed someone to

love" normally implies that I

do not need anybody to love, which is a fairly jaw-dropping statement for

a pop song in 1965, and especially from the guy who, only a few months

before, was so convincingly telling us about how "you don’t realize how much I need you". This gets you

thinking about how the lyrical hero here could be asexual (!), or too busy

with his spirituality, or too preoccupied with his touring schedule, or

simply fed up with romance because all women are evil, or whatever else comes

to an enlightened mind. But then we get to the bridge, and the simple and

boring truth reveals itself: "Had

you come some other day then it might not have been like this / But you see

now I’m too much in love". So he doesn’t need anybody just because

he has already found somebody (Pattie Boyd, presumably). BORING! I really don’t

like that line. Change it to something like "but you see now I’m too far ahead" for me, which would

preserve the mystery of the situation.

Other than

that, it’s a fine song, and it does not really sound like the Byrds — derived

from the Byrds, for sure, but just like the Byrds do not sound like Bob Dylan

when they cover Bob Dylan, so do the Beatles not sound like the Byrds when

they are inspired by the Byrds. Harrison’s 12-string sound is brighter and

sharper than McGuinn’s, creating a power-pop shimmery jangle that would later

be bread-and-butter to the likes of Big Star; the Paul/Ringo rhythm section

is tighter and springlier than the Byrds could ever want to be; and as for George’s

attitude on the song, it is actually closer to Gene Clark than to McGuinn —

that one «early Byrd» who could add a much-needed drop of bitterness and

irony to the generally starry-eyed disposition of his bandmates. Even when George

sings you see now I’m too much in love,

the line sniffs of weariness and cynicism rather than the would-be-expected jubilation.

Hence, the question «who needs to hear

the Beatles do the Byrds when you can hear the Byrds themselves?» really makes

about as much sense as asking «who

needs to hear the Beatles do ‘A Day In The Life’ when you can live your own

day in the life instead?».

In any

case, at the very least you can credit George here with one unquestionably

breakthrough-type song (with a little help from his friend Paul) and one

unquestionably solid and interesting «tribute»; this continues the pattern,

already set on Help!, of George slowly

carving out his own identity while staying well at the top of current trends

along with his elder companions. This leaves us with Ringo, who, as usual,

gets the short end of the drumstick, but since this is the Beatles, even

their short end is still longer than most of those of the competition. Apparently

‘What Goes On’ is said to have been written by John as early as 1959,

originally in Buddy Holly’s style, and then nearly recorded (but dropped for

time constraints) by the band in 1963 during the Please Please Me sessions — but I imagine that they significantly

rewrote the melody for the Ringo-sung version, because it sounds very much

alike to ‘Act Naturally’, and clearly they wanted to reward their drummer

with another country-style number since he had so much fun singing it live.

Of course,

‘What Goes On’ is a trifle, and it also suffers from the problem of an

inadequately overlong chorus (much like ‘The Word’), but Ringo’s cuddly charisma

still manages to shine through in his singing, and besides, it’s a good

indicator of just how the Beatles, at this point — or at any subsequent one

in their career, for that matter — were capable of coaxing a fun, involving,

engaging sound out of virtually nothing. 90% of «rootsy» artists would sound

yawn-inducing when playing this kind of thing, but Lennon and Harrison play

their guitar parts in such a way that it becomes (particularly during the instrumental break) a first-rate example

of «guitar weaving» technique, with the two instruments entering in a

talkative dialog mode with each other. One rarely thinks of John as a «great»

rhythm guitarist — he is certainly not a riffmeister à la Keith Richards

or Pete Townshend — but he always had this knack for extra playfulness, and

here he plays a series of short, syncopated licks, separated by lengthy pauses,

which kind of make you feel surrounded by a bunch of chaotically hopping

little froggies, croaking out in your general direction at random intervals. Around

the friendly toadies, George weaves in his own, slightly more melodic, licks,

culminating in a Carl Perkins-style solo which is also all built around

stop-and-starts. Just listen to this ambience back-to-back with the similar,

but much more straightforward ‘Act Naturally’ and again you shall see just

how far the guitarists have gone in these few months. We started out taking

our friendly horsie out for a simple ride, and we ended up in a magic swamp

filled with a swarm of persistent, but harmless little insects and amphibians.

None of that atmosphere ever really lines up with the lyrics, which mainly

try to nurse a broken heart all the way through, but who gives a damn? Okay,

so it’s Ringo Starr with a broken heart who ends up in a magic swamp, and under

these circumstances, I’m more of a magic swamp guy than an admirer of broken

hearts.

So far, as

you can see, if you thought there was even one bad song on Rubber Soul — or, to put it more

intelligently, even one song on Rubber

Soul that had nothing important or interesting to say — I’ve been proving

you wrong (at least, I’d like to think so) on every single occasion. ‘Wait’

was about as close as we’d come to a dangerous point, but even ‘Wait’ has its

redeeming qualities. We did leave the single most polarizing song for last,

and that, of course, is ‘Run For Your Life’, the one song that, in this

super-sensitive age of ours, has probably had its reputation eroded over the

decades rather than rebuilt or reinforced (not least due to Lennon’s own

sentiment, although John’s condemnation of or admiration for any of his own

songs had always been rather spontaneous — then again, he probably did depend

on Yoko’s opinions as his harshest and most trusted critic, and I’m not sure Yoko

would have approved of ‘Run For Your Life’).

I think,

actually, that the main reason ‘Run For Your Life’ exists is that the Beatles

were still thinking that they need

to close each of their LPs with a gritty rocker (how symbolic was it that Help! put ‘Dizzy Miss Lizzie’ at the

very end, rather than the penultimately-positioned ‘Yesterday’?), and no song

out of everything they recorded in those sessions was grittier than ‘Run For Your

Life’, which continues strictly in the vein of ‘You Can’t Do That’ and other Lennon

«fit-of-jealousy» type of songs. It has the dubious distinction of being one

of the few (if not the only) Beatle songs to be launched off with a direct

quotation from a «master song» — "I’d

rather see you dead, little girl than to be with another man" is

directly quoted from Elvis’ ‘Baby Let’s Play House’ — and it has John more or

less reveling in the psychopathic mode, almost to the point of being

believable (Elvis, by contrast, sang that line in more or less the same

energetic, but harmless frinedly-country-hick tone he sang the rest of the

song). The nasty brutality of his tone certainly contrasts a lot with the

cool-calm-collected irony of ‘Norwegian Wood’ or the tired sorrowfulness of ‘Girl’

or the caring soulfulness of ‘In My Life’ and can easily put off a lot of

people — but as far as I’m concerned, «bad bad John» is every bit as integral

a feature in his personality than all the others. Nobody is going to hug the John

Lennon of ‘Run For Your Life’, we’ll all go straight to the John Lennon of ‘Jealous

Guy’ for that hug if we’re ever in a huggin’ mood. But without a ‘Run For Your

Life’, there might never even have been

a ‘Jealous Guy’. I mean, for Chrissake, before you start asking forgiveness

for your sins, you need to have committed

those sins in the first place. Unless you think that ‘Run For Your Life’ is a

field guide for wronged lovers — and in that case, Charles Manson says hello

to you — you can allow yourself to simply remain impressed by its temperature

level.

Personally,

I admire the song’s passion (not to mention its catchiness), but its positioning

at the end of Rubber Soul does

return me to the issue of «thin red lines», and in this case, it still very

squarely aligns the LP with the «early» period of the Beatles rather than the

«late» period. Starting with Revolver,

the Fabs would be clearly preoccupied with the issue of «the perfect goodbye

song» — it would either be a mystical psychedelic trip into the unknown, like

‘Tomorrow Never Knows’, or an epic cosmic thing like ‘A Day In The Life’, or

a goodnight-and-goodbye song like, well, ‘Good Night’ or ‘The End’. ‘Run For Your

Life’, however, follows the earlier, simpler, less pretentious formula of «just

bring this whole thing to a stop with some rough crash-boom-bang and be done

with it!», reminding the listeners that, no matter what else we might think

of, in the end it’s only rock’n’roll and we like it. I am not even sure that

the Beatles gave any serious thought to the fact that the song’s lyrics and

attitude were so threatening — it was so normal for the times that they just

decided it was an aggressive and ass-kicking enough tune to put a lid on the LP.

Does this

in any way diminish the status of Rubber

Soul as an epoch-defining musical statement? Not any more and not any

less, I think, than the overall collective and comparative quality of its

songs. It is nowhere near what would soon be called a «conceptual album»; it

is a very natural product of gradual evolution, not revolution, with the sole

difference that evolution happened at a seriously quickened pace in the

second half of 1965 (not just for the Beatles, but for pretty much everybody

who did not consciously resist it). It does not at all feel like the result of someone saying «All right, boys,

time to go into the studio and record the greatest album of all time!» — you

could get that vibe from Sgt. Pepper,

yes, but I do not get this feeling of «we are the Beatles, so we have a

reputation to uphold and be better than everybody else» from listening to Rubber Soul. (Had it been that way, I

am pretty sure that songs like ‘Wait’, ‘Run For Your Life’, or even ‘If I Needed

Someone’ would have been vetoed for publication.) It’s just... another Beatles

album.

But, importantly, a Beatles

album fit for late 1965, which can hardly be said about the bastardized US

version that lopped off four tracks, including two of the most important ones

(‘Drive My Car’ and ‘Nowhere Man’), and replaced them with two older titles (‘I’ve

Just Seen A Face’ and ‘It’s Only Love’). I mean, a Rubber Soul that starts off with ‘I’ve Just Seen A Face’ instead

of ‘Drive My Car’? Just exactly how

far out were those people at Capitol? Every time I keep reminding myself that

the Beatles really didn’t do «concept albums» until Sgt. Pepper, my attention keeps returning to these horrible US

mutants and I remember that track grouping and sequencing is an important element

even without any kind of «concept», particularly

for the Beatles (I do not mind the bastardized versions of Rolling Stones

albums that much, for instance). To think that entire generations of young American

people grew up on these headless chickens and still regard them as the «default»

versions almost makes me sad, though I’m not going to take a cheap shot here

and prove there’s a direct straight line from there to, say, the results of

the 2024 presidential elections. (But there could be! There could be!!!)

I suppose I

am entitled to conclude the review with a bit of personal feeling that might

come as a shock after reading all that wall of text: I am not the world’s

biggest fan of Rubber Soul at all. It’s been a long, long time

since I last had a «I’m in the mood for some Beatles on the turntable» moment

(my own head is still the best turntable for any Beatles album), but if I had

one, I’d probably stretch out my hand for any of the post-1965 records. As

great as the songs are — and, frankly speaking, there is very little serious competition for this kind of quality from

anybody in 1965 — collectively, they do feel a bit slight; there’s always a

nagging feeling that they could do so much more with every single one of

these ideas had they jumped inside their heads just a year or two later. In a

way, Rubber Soul is really an «early

Beatles» album that has ripened enough to demand to be judged by «late Beatles»

standards, which puts it into an uncomfortable position. You do not hold out

tremendously huge expectations for the lyrics, arrangements, and innovative

ideas of something like A Hard Day’s Night,

where melodicity and liveliness are more important than anything else; Rubber Soul, on the other hand, goads

you into developing such expectations, and then, when they are exceeded with

subsequent albums, comes across as «that first one when they groped for

superhuman greatness, a bit blindly, though».

Not that

it’s any sort of tragedy. I mean, we all know that the Beatles were climbing

up the hill, and when you climb up a hill, one part of its slope is always

going to end up lower than the other, right? It’s really the journey that

matters — as well as the fact that 90% of Beatles songs, want it or not, have

their own personalities. The Beatles would go on to make songs even more

sophisticated, even deeper-reaching, even less predictable in every possible

aspect, but they would never do

another ‘Drive My Car’, another ‘Nowhere Man’, or even another ‘The Word’,

for that matter. So while it is sometimes fun to stop and think, "I

wonder how they would have handled that

chord change / that overdub / that special effect in 1967 or 1968?",

no possible answer to that question can in any way diminish the impressive

essence of the song in question. Nor is there any guarantee that the songs could have sounded any better: they

were, after all, the products of their own time. So, instead, let us embrace

the positive way of thinking — for instance, by admiring just how much

diversity there is on here, and how the album truly establishes the Beatles

as the «kings of pop music» in that they, like nobody else, are able to

meaningfully survey almost the entire realm of said music, putting their own

touch on all of its subgenres, from folk to rock’n’roll to R&B to Greek

to French, while also displaying a perfect or near-perfect understanding of

their essence. That is where Rubber Soul truly excels, starting up

a path that would lead all the way to the White Album and beyond.

And to

think that all it took was to change from matching suits to suede jackets!

|

![]()