BERT JANSCH

![]()

|

Recording years |

Main genre |

Music sample |

|

1965–2006 |

Folk |

Smokey River (1965) |

Page

contents:

- Bert Jansch

(1965)

BERT JANSCH

![]()

|

Recording years |

Main genre |

Music sample |

|

1965–2006 |

Folk |

Smokey River (1965) |

Page

contents:

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Album

released: April 16, 1965 |

V |

A |

L |

U |

E |

More info: |

||

|

3 |

3 |

3 |

4 |

2 |

||||

|

Tracks: 1) Strolling Down The Highway; 2)

Smokey River; 3) Oh How Your Love Is Strong; 4) I Have No Time; 5) Finches;

6) Rambling’s Going To Be The Death Of Me; 7) Veronica; 8) Needle Of Death;

9) Do You Hear Me Now?; 10) Alice’s Wonderland; 11) Running, Running From

Home; 12) Courting Blues; 13) Kasbah; 14) Dreams Of Love; 15) Angie. |

||||||||

|

REVIEW

|

||||||||

|

That said, listening to Bert’s self-titled debut,

released in April ’65, it is not that difficult to realize why that is, or

even to come to a certain understanding with fate on the subject.

Experimenting with and expanding upon the classic folk idiom is a difficult

task — one might argue that the idiom has been so well-polished and perfected

over centuries of evolution that any «tinkering» with it is liable to break

down the immediacy of effect and prevent one from being emotionally moved by

the melody. It is particularly

difficult to do so in the minimalistic setting of one guy with one acoustic

guitar; and even more difficult if the guy in question is only a passable

singer, or does not sing at all. Unlike Davey Graham, Bert Jansch actually wanted to

be a singer-songwriter — more than half of the titles here have lyrics, and

not just lyrics, but lyrics with

clearly stated messages, including anti-war and anti-drug statements. The bad

news is that, much like early Donovan, Bert never had a particularly interesting

way to deliver these messages. He was not a very good lyricist ("If

cherry trees bore fruit of gold / The birds would die, their wings would fold" is the kind of line that would

probably make Bob Dylan puke), and his singing voice is that of a haughty,

rather unpleasant, pretentious self-appointed prophet — perhaps

unintentionally so, but that’s more or less how it comes across. Unlike Donovan, let alone Paul Simon

or Nick Drake, Jansch does not generate much empathy when delivering the

vocal goods. Thus, it’s really all about the guitar playing,

which was indeed unique for 1965 and, in some ways, continues to be unique

even now. Essentially, Bert uses the synthesis of Western and Eastern, folk,

blues, and jazz patterns created by Davey Graham and takes it to the next

level, acting as a sort of Van Halen to Graham’s Eric Clapton. No better way

to demonstrate this than by comparing Graham’s original recording of

‘Anji’ and comparing it to Bert’s re-imagining on this

album — the only official cover piece, by the way, almost symbolically

«appended» to the record as its 15th track (remember that the most typical

number of songs on a UK LP at the time was 14). Graham’s original is shorter,

follows a fairly conventional chorus-verse-chorus scheme, and favors

repetition over variation. Jansch slightly speeds it up and not only

introduces a few additional phrases, but inflates many lines with extra

chords, while also playing the bass line much more loudly and prominently, so

that the song almost «rocks» in his hands. (Paul Simon, expectedly, would

make his version sound closer to Graham’s original than Jansch’s cover). But even more instructive — though much less famous

— are Bert’s own compositions, which take established picking patterns and seduce

them into becoming something completely different. ‘Smokey River’, for

instance, begins as a dark folk-blues piece, something not unlike the pattern

you hear on Bob Dylan’s ‘Ballad Of Hollis Brown’, then gets sidetracked into

a raga-like alley, with the initial blues melody «fighting» against the

intruder, temporarily getting knocked down by it, only to reappear unscathed

several bars later. The less than one minute long ‘Finches’ indeed makes me

remember the effect of Hendrix’s «three-guitars-in-one», except that here it

is all acoustic — with the bass finger doing some odd half-jazz,

half-Entwistle shit, and the others sounding as if somebody wanted to

incorporate some funky attitude into a British village folk dance. This kind

of musical language must have been totally incomprehensible to the public in

1965 — heck, I’m not even sure it’s all that comprehensible to me in 2022. ‘Alice’s Wonderland’ is explicitly named after a

Charles Mingus composition, though it is defined as "inspired by

Mingus" rather than being an actual cover — I think that the actual jazz

line that comes in around the forty seconds mark owes more to Brubeck’s ‘Take

Five’ than anything I’ve heard by Mingus. Most of the time, though, the

composition sounds like a pensive, stuttering, slightly drunk love ballad,

permanently confusing you with changes of rhythmic patterns as Bert wants to

play more than one melody at the same time but does not quite have the

necessary number of fingers for this. And on ‘Casbah’, as you could probably

expect, we hear him incorporating Arabic motives, making his guitar grumble

like some Moroccan sintir... before the melody plunges back into the same

‘Hollis Brown’ pattern. Needless to say, all of this is extremely cool and

must have sounded astonishing to young aspiring musicians in 1965, largely

used to well-established blues and folk tunings. Besides, unlike Davey

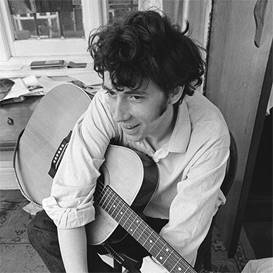

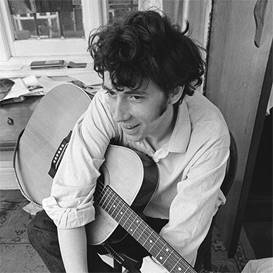

Graham, Bert Jansch looked cool — Dave

had much too much of an «academic» look, whereas the guy looking at you from

this here album cover gives out a clear sign that he truly comes from the

Jean-Paul Belmondo generation... or, at least, the Bob Dylan one. It shines

through in the music, too, which is loud, brusque, and flashy (and

surprisingly beautifully recorded, even though it was allegedly all put down

on a reel-to-reel tape recorder at the house of Bert’s engineer). My problem

with it, however, is that I constantly find myself admiring the creativity

and virtuosity much more than the spirit of the whole thing. For all the

formally amazing things Bert does with these instrumentals (and you should

probably consult a professional musicologist rather than myself if you want

them to be properly put in words), they evoke preciously few emotions in me,

for precisely those reasons I mentioned above: if you fuck too much with a

good thing, there’s always a probability that it will cease to be good. The same feeling persists on Bert’s vocal numbers.

‘Strolling Down The Highway’, which opens the album, is most likely a direct

nod to Big Bill Broonzy’s ‘Key To The Highway’ — its melody is clearly

influenced by Big Bill’s playing style (Bert was an openly acknowledged major

fan), and lyrically, the highway metaphor is used by Bert in much the same

way (compare "I got the key to the highway / Billed out and bound to

go" to "Strolling down the highway / I’m gonna get there my

way"), though, as usual, Bert has a generally poor way with words

("dusk ’til dawn I’m walking, can you hear my guitar rocking?" is a

line better fit for the likes of the Doobie Brothers than a brilliant guitar

wizard). The main problem, however, are not the lyrics and not Bert’s

un-sympathetic vocal delivery, but that I am just not sure how all those

extra ninths and other subtle embellishments add to the already

well-established vibe of Big Bill Broonzy. For sure, this is more

sophisticated, and I like how, for instance, at 0:23 into the song it breaks

into the exact chord sequence that would later form part of the acoustic

intro to George Harrison’s ‘For You Blue’ on Let It Be... but I’m just not sure that in the future I’d ever

actually prefer a bunch of songs like these to a best-of collection of the

real Big Bill. Equally questionable are Bert’s «heavy message»

songs. With ‘I Have No Time’ and ‘Do You Hear Me Now?’, Bert is trying to

send out a couple of clear anti-war messages along the lines of Dylan’s

‘Masters Of War’. But although both songs are unquestionably more melodically

tricky than the latter, their message is largely wasted. The genius of

‘Masters Of War’ is in its focused counter-attack on the listener’s brain —

Dylan’s simple, repetitive, mantraic rhythm pattern is reminiscent of a

lengthy, perfunctory string of machine-gun bursts, putting you inside a

trench with the singer; Dylan’s lyrics are masterful, and his delivery of

them feels like an angry, realistic sermon. Bert’s melodies, in contrast,

feel like embellished folk ballads, and his own attempt to raise a little

emotion on ‘Do You Hear Me Now?’ feels like an overwrought attempt from a bad

actor. Honestly, it would have been better to simply leave both tunes without

vocals altogether. A similar thing concerns what is probably the best

known song from the album — ‘Needle Of Death’, which, as you can guess, is an

anti-drug song (inspired by the recent death of one of Bert’s acquaintances),

and chronologically the first song I know to openly depict the horrors of a

drug-induced death. The lyrics, once again, are clumsy beyond belief (I can’t

help but imagine lines like "one grain of pure white snow / dissolved in

blood spread quickly to your brain / in peace your mind withdraws / your

death so near your soul can’t feel no pain" delivered in a growling

voice on some Slayer thrash metal track), and if you are no friend at all to

the English language, it’s even worse, because the song’s light, breezy

melody and Bert’s soft, pensive, not particularly distinctive delivery feel

more suitable for letting your mind wander as you relax in your back yard on

a warm Sunday afternoon than for any terrifying mental imagery of death and

decay. So give me Neil’s ‘Needle And The Damage Done’ over this any day — no

matter how much more complex Bert’s picking pattern here is than Young’s

strumming on that classic from Harvest. To conclude, I am not going to lie to you about how

dreadfully this album, and this artist, are underrated. The truth is that

there is not one, but two albums

concealed within the sleeve of Bert Jansch:

a singer-songwriter album, and an acoustic guitarist album. The

singer-songwriter album is openly bad

— way too derivative, way too poor with words and vocals, and very thin in

terms of atmosphere. The acoustic guitarist album is technically brilliant

and imaginatively innovative, but written in a language that may be difficult

to understand for a layman, and is clearly an acquired taste. Yet even so, the

combination of these two results in an intriguing oddity, as if you’re

watching a TV show where half of the dialog is written by David Simon and the

other half by the authors of Cop Rock.

In fact, it took me several listens to properly disentangle the two and solve

the puzzle — or, at least, solve it in my own way, as I’m sure quite a few

people might disagree with me on this assessment. In any case, one thing that cannot be denied is that

Bert Jansch is an essential part

of the Sixties’ universe: listening to it makes it easier to understand the

transition from «simple» folk music of the 1950s – early 1960s revival to the

advanced folk and folk-influenced «auteur music» starting off in the mid-1960s.

So start here and then think whether you are at all interested in following Jansch’s

career — he may have made better albums in the future, but arguably, he never

made any that were more startling or influential than this debut. |

||||||||

![]()