|

Not

that plugging in like that was anything short of a miracle back in 1955: ʽBo Diddleyʼ (the song) sounded like nothing else at the time. It is essentially

two parts past and one part future — combining an ancient African dance

rhythm pattern, a lyrical motive going back to an Anglo-Saxon folk tradition

(‘Hush Little Baby’), and a prominent tremolo effect on the guitar which adds

a proto-psychedelic feel to the whole thing. For a composition released on

the Chess label in the mid-1950s, this was as daring and futuristic as

possible at the time — and it also showed the label’s first willing sign to

move away from its rigorous support of the pure 12-bar blues formula (the

second sign would be Chuck Berry’s ‘Maybellene’ just a few months later — but

in strict terms of musical innovation, Chuck Berry was a conservative

traditionalist compared to Bo Diddley’s musical vision at that particular

point in time).

Unfortunately, Bo’s biggest problem was that, having

said A, he found it hard to follow it with a B. Some of his subsequent

recordings which also utilized the Bo Diddley Beat (let us abbreviate it to

BDB from now on) did improve on ‘Bo Diddley’ in sheerly technical terms —

speed, tightness, sound clarity, funnier lyrics, etc.; but none of them

succeeded in taking it any place further than the original explosion. Minor

variations on chord structure could be observed, or the addition of extra

instruments (e.g. the piano groove on ‘Hush Your Mouth’), but the general

mood, energy level, overall effect on the brain would always remain the same.

Not coincidentally, you might notice that most of the British Invasion fans

of Bo Diddley were usually quite content with covering one and only one sample of the BDB — e.g., the

Stones only did ‘Mona’, and the Animals, who probably were the best

interpreters of Bo Diddley across the Atlantic, only recorded a cover of ʽPretty Thingʼ, although they would also go on to write their own ʽThe Story Of Bo Diddleyʼ as an homage to / parody of the BDB.

But before succumbing to sadness and

disillusionment, let us also try to revive ourselves with a deeper, more thoughtful

immersion into the man’s creativity — and realize that there is much more to

Bo Diddley than the proverbial, occasionally tiresome BDB. In fact, even on

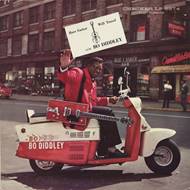

this «debut album», which is not really a proper LP but rather just a

collection of several of Bo’s A- and B-sides spanning almost four years (from

1955 to 1958), only three out of twelve tunes strictly follow the BDB proper:

ʽBo Diddleyʼ, ʽHush Your Mouthʼ (with the extra piano), and ʽPretty Thingʼ (with extra harmonica, so at least formally there is enough variation

to be forgiving). Of the others, some would probably be expected to also

follow the BDB (ʽHey Bo Diddleyʼ, for instance, which is sung to the exact same

vocal melody as ʽBo Diddleyʼ), but in reality they do not, since the rhythm

pattern has been modified to such an extent that it can no longer qualify. Finally,

other songs are altogether quite removed from the basic formula, and follow

different paths of inspiration — perhaps not as

innovative as the BDB but sometimes, in my own view, even more exciting.

As already stated, Bo Diddley, along with Chuck

Berry, was somewhat of an anomaly for the Chicago-based Chess Records, whose

overall specialization used to be less explicitly dance-oriented electric

bluesmen, from Muddy Waters to Howlin’ Wolf to Little Walter to Buddy Guy.

But with ‘Rock Around The Clock’ and other early rock’n’roll recordings

already ruffling the feathers of more time-honored genres, it is hardly

surprising that the Chess executives, too, were looking to diversify their

output with something a bit more energetic, aggressive, and commercially

viable. Besides, it’s not as if Bo Diddley himself was a total stranger to

straghtforward 12-bar blues. In his live shows at Chicago clubs, he always

played a mix of the tried-and-true with the fresh-and-daring, and there is at

least one notable example of the former on this record: ʽBefore You Accuse Meʼ, a straightahead piece of 12-bar blues somewhat in the style of Sonny

Boy Williamson, one of Chess’ major blues stars at the time. Amusingly, even

here Bo could not resist slightly speeding up the tempo, so that the final

result looks like a cross between old-fashioned blues and new-fashioned rock’n’roll.

(The 1970 cover version by Creedence Clearwater Revival is expectedly sharper

and more polished, but the song as a whole still firmly belongs in 1957).

However, the very first of Bo’s blues-based songs in

the Chicago vein, already released as the B-side to his very first single,

was anything but typical. Essentially,

ʽI’m A Manʼ simply takes Muddy Waters’ ʽHoochie Coochie Manʼ and deconstructs it down to the basics. It is as if Bo heard the song

and thought to himself, "that first bar, man, that’s the shit, who really needs anything else here now?" Complexity

fans will think of this decision as a dumb move, but when taken in the

musical and cultural context of its time, it is a classic example of brutal,

radical genius, right out there vying for first place with the likes of ʽLouie Louieʼ and ‘Blitzkrieg Bop’. In later years, the Who would be the perfect

band to cover this symbol of mythic-status virility; the Yardbirds, with

their wimpy singer, slightly less so; and too bad that it was too slow for Motörhead.

The trick here is that if you pay «emotional

attention» to ‘Hoochie Coochie Man’, you might indeed notice that the song’s

cockiest, bossiest, most self-assertive moments are the stop-and-start part

of the blues verse, whereas the "you know I’m here, everybody knows I’m

here" blues chorus already feels like a small step back. 12-bar blues,

after all, was not originally invented for advertising yourself as The Man

Who Moves Mountains; it was more of a vehicle to express depression and

melancholy than arrogance and exuberance. Thus, if you pardon the blushing

analogy, does Bo Diddley become the Larry Flynt of blues to Muddy Waters’

Hugh Hefner — and even Muddy himself had to adapt, retorting but a few months

later with his own ‘Mannish Boyʼ, essentially

the same song with slightly different lyrics. As a generally better singer

than Bo, you could argue that Muddy actually made the groove sound even more

imposing and convincing, but he would never have gotten the idea himself — «The

Originator» was there first, forcing his teacher to acknowledge some of the

new rules.

And what else did «The Originator» originate? Well,

the idea of stringing the entire song on one chord, for instance, which,

since we already mentioned Motörhead, is the genuine precursor to the

jackhammer method of headbanging. ʽHey Bo Diddleyʼ is done that way, but a more fabulous instance is ʽWho Do You Loveʼ, with its aggressive lead lines scattered along the road — not to

mention the gorgeous lyrics: "I walk 47 miles of barbed wire, I use a

cobra snake for a necktie... I got a brand new chimney made on top, made out

of human skull..." Not a lot of black lyricists used that sort of

voodooistic imagery as lightly as old Bo, who just rattles it off the wall at

top velocity, as if chased by some speed demon. But the gamble paid off —

even a band as distant from the «100% body-music» style of Bo Diddley as the

Doors covered the song during their live shows. (Question: how does one get four doors for one telephone booth? Answer: write "cobra snake"

and "human skull" on the walls). Of special note is Jody Williams’

fast, stinging, almost venomous guitar break, as sonically close a

predecessor to the classic nasty lead guitar of Mike Bloomfield as possible

(for instance, if you play the original recording of ‘Who Do You Love’ back

to back with some of Bob Dylan’s legendary live recordings from Newport ’65,

you’ll know what I’m talking about).

And these are just the most essential highlights of

the compilation. Listing the other goodies in chronological order, there is Bo’s

second single ʽDiddley Daddyʼ, opening with one of the simplest, yet most elegant

guitar figures of the decade — one which

Billy Boy Arnold, present at the session, would nix from Bo and quickly

insert in his own ʽI Wish You

Wouldʼ, which is how

all of us British Invasion fans know it (from the Yardbirds cover; ʽDiddley Daddyʼ itself evaded hit status in the UK, although the Stones and others

did play it live). From 1956, there is ʽDiddey Wah Diddeyʼ, which takes an

old slow «dance-blues» pattern of

Muddy’s, adds a playful, poppy melody resolution, and makes for an experience

that is swampy, disturbing, funny, and catchy at the same time — an ideal fit

for a young, teeth-cutting Captain Beefheart in 1966. And from 1957, there is

ʽSay Boss Manʼ, a lesser known tune that shows Bo perfectly at

home with ʽJim Dandyʼ-style danceable R&B. (I suppose that is Otis

Spann locked into that maddeningly simplistic dum-de-dum, dum-dum-de-dum

piano groove in the background, but it is hilarious to hear him try and make

a break for it during the super-short instrumental section, only to be caught

and locked back in his dum-de-dum cell by Bo fifteen seconds later!)

«Ingeniously simple» and «intelligently stupid» is

what characterizes most of these early singles, so nicely collected for us by

Chess on this 1958 compilation (note that some expanded versions of the album

also add about half a dozen bonus tracks, mostly B-sides; most of them are

expendable, and some are flat-out self-repetitions, e.g. ‘I’m Bad’, an

unimpressive sequel to ‘I’m A Man’). This makes Bo, similarly to his

contemporary Jimmy Reed, somewhat of a sacrilegious blues renegade, but this

is also precisely why we love them both — except that Jimmy Reed was

perfectly happy to find one basic formula and stick to it like glue until his

last teeth fell out, whereas Bo, as this album shows, was a restless seeker,

and in just three years’ time, he had found more than many bluesmen of the

highest caliber had found in several decades.

The BDB was merely one of these finds, and, as the first one and the one that made

him a star, it was bound to become a repetitive trademark. But there is very

little that is repetitive, uninventive, or just plain boring about Bo Diddley, an album where I myself

knew most of the songs — typically, as covered by other artists — before

hearing it. That Bo never managed to outgrow and surpass the perfection of

these early singles should not reflect poorly on one’s perception of them,

nor on one’s assessment of his artistic persona, because when we are talking

about Fifties’ artists, who else did, really? Just like everybody else, Ellas

Bates McDaniel firmly believed that one’s purpose was to find one’s own

special place in life, and once you’ve found it, hold on to it for dear life

unless someone rips it out from under you. And unlike quite a few of the less

lucky Fifties’ artists, at least he,

«the Originator», did find that place.

|

![]()