|

Anyway,

whatever the actual circumstances might have been, the bad news were that

Buddy Holly (along with his good friends Ritchie Valens and J. P. «The Big

Bopper» Richardson of ʽChantilly Laceʼs fame) was, indeed, dead, and that we would,

therefore, be forever left in the dark as to where his talent might have led

him in the golden decade of rock music. The only slight bit of consolation

was that, prior to dying, he left behind an impressive stockpile of

unfinished recordings — one that would keep the small market for devoted

Buddy fans occupied for years and years to come. But even this «good» news

was seriously soured by the fact that most of the recordings had to be seriously

tampered with in order to acquire «commercially viable» form, and that the

tamperings were not always up to par (a rather unpleasant, but not uncommon,

side of the music business; the same story would be repeated a decade later

for the prematurely departed Jimi Hendrix).

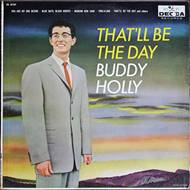

The

vaults were, in fact, opened less than a month after the funeral, although

the first installation was fairly modest: The Buddy Holly Story consisted entirely of A- and B-sides

released during the artist’s lifetime (the most recent single to be included

was ʽIt Doesn’t

Matter Anymoreʼ / ʽRaining In My Heartʼ, which came out in January, just a couple of weeks before the

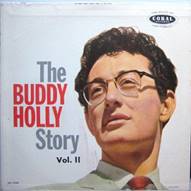

accident). Less than a year later, in response to the high chart performance

of the album, Coral followed it up with The

Buddy Holly Story Vol. II — an entirely

different story altogether, mainly consisting of «from-the-vault» stuff. Much

of it came from Buddy’s last recording session in December 1958, which he

held in the living room of his own New York apartment, taping simple acoustic

demos with nothing but his voice and guitar on show. Naturally, the record

label decided that the sound would have to be brought up to standards, and...

well, the best thing that can be said is that at least those results were

significantly better than some of the sacrileges to follow.

Since

the two LPs have this fundamental difference, it might not make too much

sense to combine them in a single review, but I shall do it anyway for a

technical reason — an entire half of the songs on The Buddy Holly Story had already gotten their LP releases in

Buddy’s lifetime, and most of them were discussed in earlier reviews, which

would make a separate entry for just six songs a little superfluous,

particularly since not all of them are masterpieces.

Taken

in chronological order, the first of these is ‘Think It Over’, the A-side of

a single released in May ’58 — a bit of 12-bar blues redone in a bouncy pop

format, with a catchy, repetitive guitar / piano riff (you’ll recognize the

same chord sequence, for instance, in the Stones’ ‘Under Assistant West Coast

Promotion Man’); arguably, the song achieved perfection only later, when it

got a new set of lyrics far more suitable to its strolling tempo, recast by

Ernie Maresca and Dion as ‘The Wanderer’.

ʽEarly In The

Morningʼ reflects a

questionable choice in covers (Bobby Darin? come on, Buddy, we know you can

do better than that!), especially given that the song is a lite-rock rewrite

of Ray Charles’ ‘I Got A Woman’.

Much better — close to a mini-masterpiece — is ʽIt's So Easyʼ, which all but sets the standard for the inventive, upbeat,

guitar-based pop song of the next decade: catchy and complex choruses and

verses going through multiple parts, melodic guitar solos with tiny

variations from first to second, a certain overtone unity between vocals and

guitars, and a bit of the Crickets’ usual roughness-round-the-edges to put a fat

checkmark in the «for rebellious teenagers» box rather than the one «for

respectable middle class audiences»— those shrill, ragged guitar licks are

definitely for the younger generation. Plus, the chorus itself — "it’s

so easy to fall in love!" — registers like an anthemic statement, less

of a personal statement this time and more like an enthusiastic invocation.

(And don’t forget the "here I go breaking all of the rules" line in

the first verse: what is this, the Crickets or Judas Priest?).

Those

sharp vibes would be, however, slightly dulled later in the year. The first

sign was ʽHeartbeatʼ, composed by Buddy’s good old friends Bob

Montgomery and Norman Petty. The arrangement of the tune has a bit of a Cuban

flavor to it, and there is a slight tinge of lounge crooning in Buddy’s

voice: compared to something like ‘Words Of Love’, with its complex lead

guitar fluctuations and intimate vocal atmosphere, ‘Heartbeat’ cannot help

but feel rather fluffy in comparison (rather unsurprising that the song would

later be covered by so many «fluff artists» — Bobby Vee, Dave Berry, Herman’s

Hermits, and the Hollies way past their prime, in 1980).

Things

get even more suspicious with the release of ʽIt Doesn't Matter Anymoreʼ, not just

because it was written by the most recent teen idol Paul Anka, but also

because it was heavily dependent on the orchestral overdubs of Dick Jacobs;

the same orchestration was also used for the B-side, ‘Raining In My Heart’,

credited to Felice and Boudleaux Bryant, the court writers for the Everly

Brothers. The orchestral arrangements are not awful per se, featuring quirky

and fun parts written for the harp, but it is fairly evident, I think, that

Buddy’s voice is less than ideal for this material — he has to really strain

and stretch to sustain all the complicated melismatic transitions on ‘Raining

In My Heart’, basically doing something he does not at all feel comfortable

with. The fact that this was the last single to be released in Buddy’s

lifetime is a tad disturbing: we shall never know if this was just a one-time

incongruence or the beginning of a possible new trend of Holly watering down

under the pressure of outside songwriters and mellowing pop tastes, but I

know for sure that if I were a

singer-songwriter and I knew I’d have to go out with a Paul Anka song, I’d

probably rescheduled that flight for several months earlier.

In

a certain way, though it expectedly does not contain as many high watermarks,

Vol. 2 is more consistent than the

first album, with ten out of twelve songs written exclusively by Holly or

co-credited to Holly and Petty. There are only two exceptions: ‘Now We’re

One’, another Bobby Darin song which was the B-side to ‘Early In The Morning’

and sounds even more inept than the A-side (if the latter was a Ray Charles

rip-off, then this one largely borrows its melody from Presley’s ‘Too Much’,

with a slight infusion of ‘Money Honey’), and Petty’s ‘Moondreams’, a ballad

Buddy had originally recorded with the Norman Petty Trio back in 1957 and

then revived in late 1958 with more of Jacobs’ orchestral arrangements. It is

not a very good song, honestly, sounding like a Doris Day standard more than

anything else, and the clichéd «salon gypsy violin solo» makes things

even worse.

Other

than that, however, Vol. 2 gives

us plenty of worthy goodies. Returning to chronological order, ‘Take Your

Time’ (the original B-side to ‘Rave On’) is a rare case of Buddy being

explicitly shadowed by a prominent Hammond organ, which is a refreshing

change from permanent guitar dependence. (It should also probably be noted

for being one of the first pop-rock songs in which the protagonist "can wait", as opposed to all

those other songs in which he most assuredly can’t — ever the gentleman, Buddy Holly puts no pressure on his

maiden of choice).

Even

more impressive is ʽWell... All

Rightʼ, the original

B-side to ‘Heartbeat’ which, honestly, should have been the A-side: remember

all those artists listed above who covered ‘Heartbeat’? ‘Well... All Right’,

on the contrary, was covered by Blind Faith, Santana, and the Smithereens

(also Kid Rock, but we’ll try to let this one slide, okay?). It’s a song that

seems so far ahead of its own time that it never sounded out of place on

Blind Faith’s self-titled album — in fact, its rhythmic strum has quite a bit

in common with the Beatles’ ‘Get Back’, except that Holly’s acoustic melody

is muted and introvert, suitable for the intimate nature of the song, as

expressed in lines like "...the dreams and wishes you wish / in the

night when the lights are low" (my personal mondegreen with the song is

that I always hear that line as "the dreams and wishes Jewish", and subsequently get

visions of Buddy Holly as a young Orthodox rebel quietly protesting against

the yichud). The song’s lyrics and melody both point a possible way

to a much more mature, introspective Holly bringing wisdom and responsibility

to teenage mentality — the line that would eventually be endorsed by Brian

Wilson and the Beach Boys, but in their own way, close to Buddy Holly’s

artistic ideology but very different in terms of melodic and harmonic

realisation.

All

the remaining songs on the album were released posthumously, and it is not

clear if all of them would have been endorsed by the artist had he lived: for

instance, ‘Peggy Sue Got Married’, the tongue-in-cheek sequel to ‘Peggy Sue’,

might have been written and demoed by Buddy as just a joke — it has the exact

same melody and clearly follows the pattern of LaVern Baker’s original ‘Jim

Dandy’ vs. ‘Jim Dandy Got Married’. But the song was still picked up by the

Coral executives, dusted off, overdubbed with a rhythm section and rather

corny-sounding backing vocals, and released as the first single after Buddy’s

death — though, honestly, the A-side should have been ‘Crying, Waiting,

Hoping’, a song particularly famous for its clever overdubbing by the rest of

the Crickets, who had to work with Buddy’s demo and fill in the «echo» vocals

for the title, one of the few «post-Buddy» creative decisions on his work

that has become universally accepted even after the original demo had

surfaced — probably because without the echo vocals the little ladder that

Buddy has constructed in the place of the vocal melody seems to be naturally

lacking several steps, which his co-workers are only too happy to be able to

fill in. This particular tune the Beatles did not improve on, when they

played it live on the BBC — maybe because they highlighted the wrong George

on it (Harrison, whose vocal performance was quite flat compared to Buddy’s,

instead of Martin, who may have given them a few clues on how to gloss it up

properly).

The

remaining five songs are of varying quality, which is even more difficult to

assess because of all the sappy orchestral overdubs. I don’t care much for

‘True Love Ways’, another standard-type ballad that’s more Sinatra than Buddy

Holly; I do care for ‘That Makes It

Tough’, as long as somebody bothers to strip it clean of the circa-1950 style

old-fashioned doo-wop backing vocals — in essence, it feels like a

potentially gritty country ballad that might have been great in the hands of

Hank Williams. ‘What To Do’ is a nice, but not outstanding, upbeat

pop-rocker; ‘Learning The Game’ is a good example of folk-pop that I can

easily envisage coming from the likes of the Searchers; and ‘That’s What They

Say’ was perfectly placed as the farewell song at the end of the album — many

a tear must have been shed at hearing Buddy sing "there comes a time for

everybody" in such a decisive, final

style, and even if he is obviously singing about true love rather than

you-know-what, this does not make the verse about "I didn’t hear them

say a word of when that time will be / I only know that what they say has not

come true for me" any less bitter-ironic.

In

retrospect, the two volumes of The

Buddy Holly Story do a good job of illustrating all of the artist’s

sides, the great ones and the weak ones, the genius and the corniness. Truth

of the matter is, Buddy Holly was not an «Artiste» (with that decisive final -e):

all he wanted, like pretty much everyone else at the time, was to make pop

singles that would bring fame and fortune, and he was equally happy to record

melodically and spiritually exciting songs one day, and a bunch of corny

schlock the other one — which is why, honestly, I remain fairly skeptical

about the idea that, had he lived, he might have taken pop music to the same

heights as the greatest artists of the next decade. (At best, I think, he

might have attained the reputation of somebody like Roy Orbison — consistent

and always respectable, but well off the cutting edge once the British

Invasion swept away American resistance).

On

the other hand, even his late period songs such as ‘Well... All Right’ and

‘Crying, Waiting, Hoping’ show that he was anything but spent as an interesting songwriter, and there is really no

telling what that songwriting style would have evolved into with the arrival

of new trends, from surf-rock to Merseybeat. Clearly, it would be «soft» — we

see a very clear tendency to tone down Buddy’s rocking side from his early to

his late days — but what sort of «soft» (Roy Orbison-soft? Brian Wilson-soft?

Engelbert Humperdinck-soft?) remains unclear. So just blame it on Paul

McCartney.

|

![]()