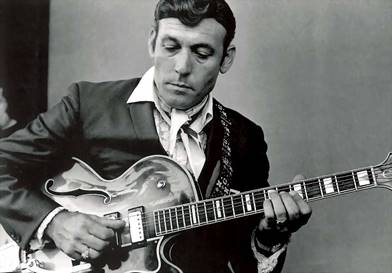

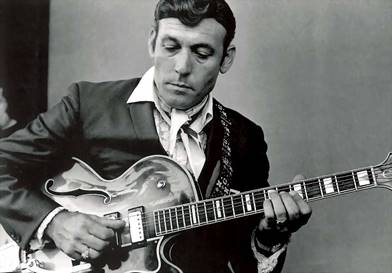

CARL PERKINS

![]()

|

Recording years |

Main genre |

Music sample |

|

1955–1998 |

Early rock’n’roll |

Boppin’ The Blues (1956) |

Page

contents:

- Dance Album Of Carl

Perkins (1957)

- Whole

Lotta Shakin’ (1958)

CARL PERKINS

![]()

|

Recording years |

Main genre |

Music sample |

|

1955–1998 |

Early rock’n’roll |

Boppin’ The Blues (1956) |

Page

contents:

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Album

released: 1957 |

V |

A |

L |

U |

E |

More info: |

||

|

2 |

4 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

||||

|

Tracks: 1) Blue

Suede Shoes; 2) Movie Magg; 3) Sure To Fall; 4) Gone, Gone, Gone; 5) Honey

Don’t; 6) Only You; 7) Tennessee; 8) Right String, Wrong Yo-Yo; 9) Everybody’s

Trying To Be My Baby; 10) Matchbox; 11) Your True Love; 12) Boppin’ The Blues;

13*) All Mama’s Children. |

||||||||

|

Like

most LPs ever put out by Sun Records, Carl Perkins’ only «original» long

player from his four-year tenure with the label is really just a chaotic

compilation of A-side, B-side, and outtake material. But even in this form,

or, actually, because of this form,

it still counts as one of the most impressive and fun-filled LPs from the rockabilly

era. Not to mention influential — come to think of it, which other single LP

from the era could boast a whole three songs to be officially covered by the

Beatles? Not Little Richard, not Chuck Berry, not Buddy Holly, not the

Miracles or the Temptations: meet the one and only rocker whose songs really screamed to be covered by the

Fab Four. |

||||||||

|

Perhaps

the most important thing about Carl Perkins is that, of all the notorious

rockabilly people of the era, he was the one who took the most care to

faithfully preserve the «simple country boy» essence in his music. Bill Haley

probably came close, but in all honesty, Haley did not have that much of an

individual personality: his backing band, the Comets, was at least as

important as its frontman, blending the old touch of country-western with a

Louis Jordan-esque big-band jump-blues entertainment approach. Perkins, on

the other hand, wrote his own songs (or radically reinvented traditional

ones), sang his own melodies, played his own lead guitar, and, overall, made

it so that we rarely ever remember anything about his sidemen during his

recording sessions. Quick, name the bass player and the drummer on ʽBlue Suede Shoesʼ without googling! Yeah, right. Not even Google can help that easily.

(For the record: Carl’s brother Clayton Perkins played bass, Carl’s other brother Jay Perkins played

acoustic guitar, and W. S. Holland, the future drummer for Johnny Cash’s

Tennessee Three, played the drums. And now you can forget all about it). Thus,

Carl is essentially a lone wolf, and in that status, gets the right to his

own influences and nobody else’s — and chief among those influences is the

Grand Ole Opry, with Bill Monroe, Gene Autry, and Hank Williams as his major

idols. The good news for those city slickers who (like me) feel a bit iffy

when it comes to «pure» country music, is that Carl clearly preferred his country with a sharper edge, and

if anything, his rockabilly style is a direct continuation of Hank’s

faster-paced, boogie-based material like ʽMove It On Overʼ. Although Carl’s

own spirit was never as tempestuous or torturous as Hank’s (not a single

Perkins song shows any signs of such acute bitterness), he always had a thing

for raw excitement, energy, speed, humor, good-natured irony — anything that

would put a smile on your face and an itch in your feet. Most

importantly, Carl’s «lonerism» is responsible for making ʽBlue Suede Shoesʼ into one of the coolest songs of its era — and the lyrics had a lot to do with it: "Don’t you step on MY blue suede shoes...", sung in

a friendly enough tone but with a very clear hint of a threat. This is really

where all the Gene Vincents of this world come from: the «rebels» were

inspired by the individualistic cockiness of a plain, harmless, friendly

«country bumpkin» who inadvertently tapped right into the spinal cord of his

era. ʽRock Around The

Clockʼ was a good

enough count-off for the rock revolution, but it was a general fun party

song. ʽBlue Suede

Shoesʼ takes us into

one particular corner of that party, where one particularly self-consciously

hip guy is busy protecting his own particular interests against the whole

world, and backing them with sharp bluesy lead guitar licks that sound like a

bunch of slaps in the face of whoever has been unlucky enough to step on the

protagonist’s lucky footwear. There

is a myth going around that Elvis «stole» the song from Carl while the latter

was recuperating in the hospital after a car accident, and that this

effectively put an end to Carl’s career as a pop star. In reality, Carl never

had the makings of a star, and the image of a «teen idol» would have probably

never sat too well with him in the first place — he was, first and foremost,

a songwriter and a guitar player — none of which, however, prevented his ʽBlue Suede Shoesʼ from going all

the way to the top of the charts, while Presley’s version (a classic in its

own right, no doubt about that) stuck at No. 20 (admittedly, RCA people

agreed to hold back the release until Carl’s version lost its original

freshness — see, there was a time

when record industry people could occasionally show signs of gentlemanly

conduct). Already

ʽBoppin’ The

Bluesʼ, the direct follow-up

to ʽBlue Suede

Shoesʼ, did not chart

as high (No. 7 was its peak) — and it wasn’t

Elvis that had anything to do with it, but rather the fact that the song was

comparatively toothless in comparison, a fairly formulaic rockabilly creation

describing the simple joys of rock’n’roll dancing with little challenge or

defiance. In the hot, tense competitive air of early 1956, Carl soon lost

the lead, and although the next three years would see him reeling between

inspiration and repetition, the record-buying public pretty much wrote him

off as a one-hit wonder and focused on Elvis instead. In addition, Carl

loyally stuck with Sun Records through those years, meaning that he couldn’t

even begin to hope for the kind of promotion that Elvis got (on the positive

side, Carl never got to have his own Colonel Parker). It

is a doggone shame, though, that

such fate also prevented a great tune like ʽMatchboxʼ from charting — without the Beatles’ support, it might have altogether sunk into

oblivion, but really, few pop songs sounded as harshly serious and

deep-reaching in 1957 as that particular reincarnation of an old, old, old

blues song by Blind Lemon Jefferson. When those echoing, distant-thunder-like

boogie chords start rattling around the room, it’s almost as if you were

being intentionally prepared for some important social statement — and in a

way, you are, since Carl preserves many of the original lyrics, infusing the

song with a blues-based sense of outcast loneliness instead of the usual

get-up-and-dance stuff. "I’m an ol’ poor boy, long way from home"

is, after all, quite different from "lay off of my blue suede

shoes". It might even be argued that «socially conscious» rock’n’roll

music starts somewhere around this bend, even if Carl would probably never

describe himself as rock’s first protest artist. On

a personal note, I must say that ʽHoney Don’t’

feels to me as one of the very few rock and pop songs by other artists that

the Beatles did not manage to

improve upon — and not because Ringo is a worse singer than Carl (he actually

did a fine job to preserve the tune’s humor), but because George Harrison

never really got around to learning all the tricks in Carl’s playing bag: as

rough as the production is on the original, Perkins compensates for it with a

series of improvised «muffled» licks that George did not even try to copy,

playing in a «cleaner» style that left less room for dirty rock’n’roll

excitement. (On the other hand, George did

get the upper hand on ʽEverybody’s

Trying To Be My Babyʼ by managing to

raise the tension on the lengthy second instrumental break, whereas in Carl’s

version it pretty much stays the same throughout). Of

the twelve songs assembled here, only a couple are relative clunkers: ʽTennesseeʼ, in particular,

sounds as silly as it is sincere, a heartfelt tribute to Carl’s native state

with a hillbillyish chorus and somewhat uncomfortable lyrics that, among

other things, urge us to give credit to the fact that "they made the

first atomic tomb in Tennessee" (a somewhat inaccurate reference to Oak

Ridge, but even if it were

accurate, I’m not sure I would want to boast about it even at the height of

the Cold War). Pompous, vocally demanding ballads are also not one of Carl’s

fortes (ʽOnly Youʼ), but he can

come up with a highly catchy homely, simple country ballad when he puts his

heart into it — ʽSure To Fallʼ, with its melody almost completely based on

serenading trills, is quite a beautiful little piece. One

of the most interesting things about comparing old rockabilly records from

the mid-to-late 1950s is the relative proportion of their ingredients. Some

veer closer to R&B, some to electric blues, some to «whitebread» pop,

some are jazzier, some vaudevillian. From that point of view, Dance Album Of Carl Perkins is a

curious mix of something very highly conservative with an explosive energy

that is nevertheless kept under strict control, like a fire burning steady

and brightly, but only within a rigidly set limit. Had all rock’n’roll looked

like Carl Perkins in the 1950s, it would probably have taken us a much, much

longer way to get where we are right now — but, on the other hand, maybe we

wouldn’t already be wondering where exactly is it possible to go from here. |

||||||||

![]()

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Album

released: 1958 |

V |

A |

L |

U |

E |

More info: |

||

|

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

||||

|

Tracks: 1) Whole Lotta Shakin’; 2) Tutti

Frutti; 3) Shake, Rattle & Roll; 4) Sittin’ On Top Of The World; 5) Ready

Teddy; 6) Long Tall Sally; 7) That’s All Right; 8) Where The Rio De Rosa

Flows; 9) Good Rockin’ Tonight; 10) I Got A Woman; 11) Hey, Good Lookin’;

12) Jenny Jenny. |

||||||||

|

Sooner

or later, every successful Sun artist had to leave Sun Records for the big

time, just because such was the way of the world; few Sun artists, however, upon

leaving their alma mater, ended up in such an ignoble position as Carl Perkins.

Although Columbia Records, where he found himself together with his buddy

Johnny Cash, still allowed him to put out a few original compositions as

singles, the one and only LP he cut in the 1950s for the label was this clearly

disappointing, if not downright dreadful, collection of covers. A single look

at the tracklist shows that the record consists of almost nothing but major

and well worn-out (by 1958 already) rock’n’roll hits for Carl’s Sun partners

Elvis Presley and Jerry Lee Lewis, as well as other notorious rock’n’rollers

like Bill Haley and Little Richard. Naturally, the last thing the world needed in late 1958 was yet another take on

the classics from an artist whose chief asset had always been songwriting,

not impersonating. |

||||||||

|

I

would not dare say that all of this sounds completely forced and unnatural, or

that Carl was clearly not having

himself a ball with at least some of this stuff — he may not have written

these songs, but there is little doubt that he loved all of them, since they

are so right up his own alley of interests. The problem is that he does not

seem at all to be in real charge of the sessions. Although Columbia’s

production values are slightly (only

slightly) higher than those of Sun, the actual recordings are not at all

beneficial for Carl. The sound is almost completely dominated by session

players, such as the 47-year old Marvin Hughes, a veteran of Nashville piano

playing, and the somewhat younger jazz saxophonist Andy Goodrich — both of

them obvious, but hardly outstanding, professionals who loyally deliver the

goods, but way too often end up drowning out Carl’s vocals and even Carl’s

guitar playing to the point that it becomes unclear why the hell would

Columbia Records even bother signing this guy up. The

only curious, and moderately successful, idea on the entire album was to turn

ʽSittin’ On Top

Of The Worldʼ, formerly

played as a slow country-blues piece by everybody from the Mississippi

Sheiks to Howlin’ Wolf, into a lightning-speed rock’n’roll number — thus, giving

it essentially the same treatment that Carl earlier gave to Blind Lemon

Jefferson’s ʽMatchbox Bluesʼ during his tenure at Sun. Unfortunately, while ʽMatchboxʼ managed to sound

gritty and serious, with a guitar sound bordering on proto-punkish because of

its angry vibe, this rendition, in

comparison, is just a fun bit of frolick with no guitar solos and a barely

discernible rhythm guitar part. If they could at least get somebody like King

Curtis to complete the transformation of the song into Perkins’ answer to

‘Yakety Yak’, it would have made some kind of sense; the way it is, it takes

most of it out of the original and adds little else. Vocal-wise,

Carl is in good form, but he never gives other people’s songs the same kind

of sly, sexy reading that he usually gives his own. Every now and then, he

tends to overscream (sometimes getting out of tune in the process), and,

worst of all, as long as you preserve your basis for comparison and as long

as the voices of Little Richard, Elvis, and even Jerry Lee Lewis doing the

same songs still ring out in your head, Carl’s relative lack of power and

singing technique remains a constant problem. On his cover of Hank Williams’ ʽHey, Good Lookinʼ, he does not even try: the original was all about making you swoon by drawing out those opening notes

("h-e-e-ey, good lookin’, wha-a-a-t you got cookin'..."), while

Carl just swallows them completely — which is all the more strange, given

that it didn’t used to be that bad:

at least on songs such as ʽSure To Fallʼ he could show some impressive range. The

further down you go, the more it begins feeling suspiciously like an

intentionally butchered hackjob: I do not know the details, but either Carl

was just pissed off at his new label for demanding that he cover other people’s

hits, or some things simply did not work out. He may have been uncomfortable

with the new session band, or the new recording studio, or something else,

but one thing is for certain: Whole

Lotta Shakin’ is quite far from being the best possible introduction to

the guy’s songwriting and overall charismatic genius. One might even want to

go further and grumble that it is one of those albums which explains the

beginning of the temporary decline of rock’n’roll in the late 1950s — with

lackluster sessions like these coming from established icons, you’d certainly

want to think that rambunctious rock’n’roll had passed its prime, and that it

was high time to try out something truly

new — like Chubby Checker, or Bobby Darin. It

must be added, for honesty’s sake, that even in terms of original songwriting

Carl never achieved the same level of quality and immortality with Columbia

as he did with Sun. Pretty much every textbook classic he did, about a dozen

or so of them, was recorded during his Sun period; I don’t think that even

one song from the Columbia years can boast as much publicity or covers by

subsequent artists as that early golden bunch. You can clearly feel the

difference yourself by comparing the early Sun version of

‘Pink Pedal Pushers’ and the Columbia re-recording

of the same title (which, I think, was officially released earlier than the

Sun recording, which lingered in the archives for some time). The former has

a shallower, dirtier, more classic rockabilly-style sound; the latter is

denser, deeper, cleaner, and ultimately, less inciting and seductive —

lacking the original’s little scat intro and discarding its

let’s-take-the-elevator-to-hell descending bassline. At

least it is good to know that in those troubled years for rock’n’roll, Carl

never truly slipped into schmaltz (which would have been hard for him to do

anyway due to his naturally rough voice, totally unfit for sugary crooning).

But whether it was the fault of Columbia or simply that of the spirit of the

times (it was certainly not related

to his accident, which took place in early 1956 and was followed by a whole

lot of raunchy classics for Sun Records), his act got cleaned up and

stiffened all the same. It is things like these that truly make you believe

in voodoo magic — doubtless, somebody must have placed a hex on rock’n’roll

music by mid-1958 or something. |

||||||||

![]()