|

REVIEW REVIEW

On

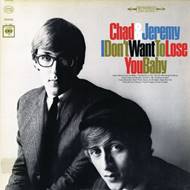

March 27, 1965, Chad & Jeremy signed a contract with Columbia Records,

which symbolized their acceptance into the big leagues — apart from Bob Dylan

himself, one of Columbia’s leading artists at the time were Simon &

Garfunkel, and apparently the idea of propping up their American superstars

with a thematically similar British duo really appealed to somebody in the

management. To seal the deal, the kids were introduced to Van McCoy, one of

the major songwriters for the April-Blackwood concern, tightly connected with

Columbia — a reasonable choice, given McCoy’s knack for adorning the

compositions aimed at his R&B clients with «Europop» stylizations, e.g.

Barbara Lewis’ ‘I’m Yours’ and the like. For Chad & Jeremy, McCoy quickly

came up with ‘Before And After’, a song that starts out almost exactly the

same way as ‘I’m Yours’, except the mode is predictably changed from major to

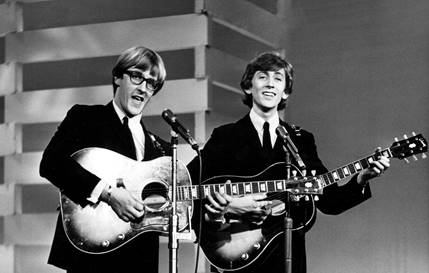

minor, because S-A-D. "His

future’s bright, my future’s dim / And all the dreams we shared, you share

with him" — it probably took McCoy one listen to any select side of

any select Chad & Jeremy LP to work out their «eternal bespectacled

loser» vibe. Admittedly, it’s a pretty well-written song, with a clever

build-up that could have been really

effective if the song were ever tried out by somebody a little less

milquetoast than those guys (as it happens, it was first recorded by The

Fleetwoods, then covered by Lesley Gore and The American Breed, and all those versions are even more

milquetoast than Chad & Jeremy’s. Dang!).

|

|

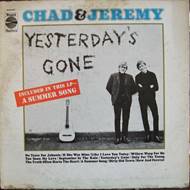

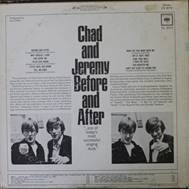

Anyway, the entire album, which they rather quickly

dashed off for Columbia in March 1965, sort of represents the peak of Chad

& Jeremy’s «Melancholic Loserville» vibe — most of the songs are dreary

and brooding, dealing with either the paranoid fear of losing your loved one

or the depressed aftermath of the breakup. Oh yes, there’s also that third

theme — quiet and shy adoration of the object of your desire without ever

getting the courage to turn dreams into action. That, for the record, is the

typical topic for the upbeat Chad

& Jeremy song: ‘Little Does She Know’, which I’m kinda sympathetic to,

stomps around with the smoothened and softened martial bravado of a Dave

Clark Five number, but where the similar DC5 number would be a triumphant

celebration of having gotten the girl, Chad & Jeremy can only admit that

"I’m gonna show her I could be

the apple of her eye", and get the appropriate support from a

squealy-squeaky two-note guitar riff in the background (is that even guitar?

sounds almost like a theremin to me). Don’t be too harsh on them, though. As

a sorely shy loser on that front in high school myself, I can seriously

relate, and so can hundreds of thousands of us nerdy guys.

No wonder, then, that all those Beatles comparisons,

which were quite apt for the previous two albums, gradually fade away now,

replaced by a vibe that is clearly more Zombies-like in essence, even if

these guys do not share much of the Zombies’ melodic inventiveness, and their

backing band lacks a proper musical talent like Rod Argent to transform the

vibe into truly memorable and heavy-hitting art. It is a vibe that comes very

naturally to them, and it would be unjust to attack any of those self-penned

tracks for insincerity or lack of taste. In fact, each and every one of them feels

more sincere than, say, something

like ‘Baby’s In Black’, whose emotional palette is complicated but, as far as

I can tell, hardly produces a lot of associations with either true black or true blue. But ‘Baby’s In Black’ still sticks in your head, while a

song like ‘Say It Isn’t True’, despite formal catchiness and a nice stereo

separation of the two guitars, does not.

A good hint is provided by the fact that when the

"well I know that I shouldn’t

believe it..." bridge section comes along, there are some clearly

discernible vocal parallels there with the bridge section of ‘How Do You Do

It?’, that soft little pop tune which The Beatles had rejected in 1963 in

favor of ‘Please Please Me’ and which went on to be associated with Gerry

& The Pacemakers instead. It shows that Chad & Jeremy’s songwriting

was really still stuck in the early Sixties, unable to cross the simplistic

teen-pop barrier that, for both The Beatles and The Zombies, had already been

left far behind by early 1965. Essentially, this is the «formula of 1963»

that, instead of being exchanged for something substantially more refined and

advanced, is simply polished and improved with better production, slightly

more thoughtful lyrics, and a bit of that pensive singer-songwriter vibe that

gives the final product a more sincere feel, like now this stuff is really coming from the heart rather

than merely written as a piece of commercial ware.

Paradoxically, this gives the album... well, not a unique vibe for 1965, as obviously

there were plenty of similar well-behaved mediocrities all over the place,

but a vibe that, when you let it soak through your living room, generates

more nostalgia for the spring and summer months of 1965 than any Beatles

record. The Beatles, after all, strived (perhaps unconsciously so) to make

their music relatively timeless, with each of their albums existing more in

the context of their other albums

rather than in the context of the time and space around it; meanwhile, a

record like Before & After

best exists in the context of something like set of 3 retro hair model posters from "American

Hairdresser" (in stock on eBay for $21.00). It’s a kind of nostalgia

that I can certainly get behind, though, to some extent at least.

However, I can only get behind it as long as Chad

& Jeremy are truly and sincerely doing their thing — singing nerdy teen

serenades or spinning teen tales of broken hearts. Conversely, when they try

on another old folk shanty nicked from one of Joan Baez’s albums (‘Fare Thee

Well’), they exchange the 1965 vibe for a wannabe-Greenwich Village sound

that is even less authentic than Peter, Paul & Mary. And God help them

when they decide to rock out: ‘Evil-Hearted Me’ is a diet take on ‘Long Tall

Sally’ (they even manage to copy Harrison’s lead guitar part almost

note-for-note!), one of those proverbial «we need to include a rock’n’roll

number to retain the hipness quotient» moments where you begin to wonder

about what happened to the concept of human dignity.

They fare a little better with the cover of Gordon

Lightfoot’s ‘For Lovin’ Me’, which gets a nice twin guitar arrangement and a

more vocally polished sheen than the original — even if the song’s lyrical

message, with its (rather ugly, but highly traditional) Don Giovanni

attitude, seems fairly distant from the typical Chad & Jeremy formula.

Feels a bit weird for the same guys who, just a moment ago, complained about

losing their lover to an alpha competitor, now try to convince us that "I ain’t the kind to hang around / With any

new love that I found". But that’s just a matter of artistic

transformation, and even so, there is so much warmth in the singers’

harmonies that the breaking of character comes across only when you pay

serious attention to the lyrics.

It does cast a bit of a shadow on songs like ‘Tell Me

Baby’, which is probably one of the best-written and arranged compositions

on here — the horns and strings could use a bit more energy, but the

triumphant way in which they waltz around each other is still infectious, and

the resolution of the melody is proverbially «glorious». However, given the

Gordon Lightfoot cover that preceded it, words like "can’t hide it from you, I want you so bad,

if he’s gone, I’ll be sorry for you, but for me I’ll be glad" come

across as, if not exactly «predatorial» (Chad & Jeremy look about as much

as predators as a couple of purry kittens... well, okay, kittens are predators), then at least a bit

sleazy. Then again, whoever said shy nerdy guys cannot be ruthless womanizers

deep down inside?..

To sum up, Before

& After has about a half-dozen expertly written, adequately

performed, and modestly catchy folk-pop or baroque-pop numbers, whose main

problem is an irritating lack of sharpness.

Give this stuff a bit more crunch, make these guys’ harmonies sometimes ring

out in true Beatles or Zombies fashion, let the songs sound with a little

less of that «we don’t want to offend anyone’s auditory senses, no really we

don’t!» attitude, and you just might have something there. As it is, the

dreamy comatose aura that Chad & Jeremy self-imposed on themselves became

their trademark and their curse.

Even when the goddamn songs are good, they’re so smoothly oiled that they

just slip out of your brain.

The remastered edition of the album on CD throws on

lots of bonus tracks, alternate versions, and awful San Remo-style outtakes

of the duo singing in Italian. Most of these are forgettable, but perhaps a

word of kindness should be spoken about the two tracks credited to «Chad

& Jill» — Chad Stuart’s duets with his wife, who temporarily filled in as

his musical partner while Jeremy was away in London, trying out for a music

hall acting career (a move that he has since come to regret, blaming it for

effectively killing off their American popularity). ‘The Cruel War’, in

particular, is a highlight — a harpsichord-led, livelied-up baroque-pop

rearrangement of the old anti-war folk song, popularized by Peter, Paul &

Mary, and Jill Stuart has one of those lovely fair-maiden voices that,

unfortunately, never went anywhere (allegedly, she felt herself roped into

the business, never aspiring for a professional musical career).

|

![]()