|

To

knock the hype down just a little bit, let us first toss out the clunkers —

no Chuck Berry album is completely

filler-free, though even the man’s misses at the time have an intriguing

aspect to them. First on the list is ‘Hey Pedro’, the original B-side to

‘Carol’, a limp, repetitive, utterly passion-free Latin vamp over which Chuck

ad-libs some parodic lines in his mock-Cuban accent, already familiar from

‘La Juanda’ — I don’t exactly know what in particular Chuck could have against

Cubans (he didn’t spend that much

time in Florida, did he?), but once again, his sense of humor totally fails

him once he puts aside his rock’n’roll spirits and substitutes them for

parodies of stereotypes. And I wouldn’t even mind an offensive parody of a

stereotype if the music was up to par — but this shit sounds like it was just

quickly tossed off in a couple of minutes when he suddenly realized he’d

booked studio time without writing enough material.

Next

on the list are two odd, but ultimately not-too-exciting A-sides on which

Chuck also tried to do something «different». ‘Anthony Boy’ seems to be

picking up the vibe of ‘School Days’ with its all-too-personal tale of an

unlucky schoolboy bullied and humiliated by his wicked girl classmates — but

if ‘School Days’ was a rebellious anthem of rock’n’roll as a means of

liberation from the tyranny of the classroom, then ‘Anthony Boy’ is basically

just a joke song; deceptively opening with the exact same guitar trill as

‘School Days’, it then immediately turns into a goofy boy scout marching

ditty which has Chuck Berry inventing Herman’s Hermits five years before

Herman’s Hermits invented themselves. As a filler B-side, it would have been

comprehensible; as an A-side, it was an embarrassment, and predictably opened

1959 as one of Chuck’s biggest flops — what was he even thinking?

Only

marginally better — though for completely different reasons — is ‘Jo Jo

Gunne’, a very strange rocking tune which opens with the usual ‘Roll Over

Beethoven / Johnny B. Goode / Carol’ riff but quickly turns into another

repetitive, echoey, muddy vamp over which Chuck tells us a long, long, LONG

story of the adventures of... wild animals in Africa "in ancient

history, four thousand B.C.". All I remember from the narrative is that

there was a monkey, a lion, and a kangaroo (Chuck’s knowledge of African

zoology certainly leaves a lot to be desired, but then again, maybe he

thought four thousand B.C. was such a long time ago, you couldn’t go wrong

even if you threw in some mammoths and dinosaurs), but otherwise, the

narrative went absolutely nowhere, the humor was non-existent, the brief

in-between verse breaks had the sole purpose of letting Chuck catch a breath,

and the entire song seemed to have one and only one purpose — to make you wonder

if Chuck Berry had really gone crazy or if he was just throwing one of his

pranks on his audiences. (Apparently, it did impress some people — like a few

members of the great psychedelic band Spirit, for instance — enough to have

them form a band named Jo Jo Gunne in the early 1970s, which was probably the

biggest legacy the song left behind).

Finally,

the sole LP-only track here, closing off the album, is ‘Blues For Hawaiians’,

an instrumental exploring the same moods and techniques that Chuck had already

demonstrated earlier on the Hawaiian-influenced ‘Deep Feeling’, except this

time he really goes overboard with the «floating» sliding sound. It feels

cool for a few seconds, but quickly gets tedious — Chuck is no virtuoso, and

he cannot achieve the same level of expressivity with his «Hawaiian guitar»

that he can with his rock’n’roll antics, so ultimately it’s just three and a

half minutes of lost time for all of us.

But

once we have sacrificed all that stuff to the hungry God of Filler, there are

still eight absolutely indispensable classics left on the platter — songs

that I am really reluctant to comment upon, because what sort of new things

under the sun could be said about ‘Roll Over Beethoven’ or ‘Johnny B. Goode’?

Well, since pretty much all of these are known from multiple cover versions

as well, let me just run a brief comparative analysis to see if any of those

had made the original «expendable» or if there are certain elements about

Chuck’s own versions that still kick the shit out of everybody else. Starting

off in chronological order, we have...

...well,

‘Maybellene’, of course, Chuck’s very first single that put him on the map. Never, as of yet, heard it done better

by anybody — perhaps the original is grossly lo-fi even compared to Chuck’s later

recordings, with the lead guitar sounding as if it were played out of a

tightly zipped suitcase, but the tempo, the jackhammer, proto-Motörhead

percussion, the rapid fire passion in the vocals; all of these elements

create a feel of overdrive which often, though not always, characterizes a

great artist’s first offering, when he knows

it’s now or never, it’s gonna make him or break him, and gives out 200%.

Listen to that guitar break — the mad flurry of Berry-licks loosed like

shrapnel on the audience. Not only did nobody

play guitar like this back in 1955, but I don’t think even Chuck himself

played it quite like that again ever after. Who’s gonna kick his ass over

this one? Gerry and the Pacemakers? Don’t make me laugh.

‘Roll

Over Beethoven’ — I think the one «alternate» version we all have in mind is

the Beatles’, with George Harrison taking lead vocals. (Well, there’s also

ELO, of course, but any version of ‘Roll Over Beethoven’ that crosses Chuck

Berry with actual Beethoven has to

be regarded from a «meta» perspective, so we’ll leave that one out). Beatles’

covers of Chuck Berry are not to be laughed off — remember how they so fully

realized the anthemic potential of ‘Rock’n’Roll Music’ — but what they always

tend to do is make the songs sound more serious than they were originally

intended. Here, for instance, they (a) slightly slow down the tempo, so that

you might get a little more inclination to listen and a little less to dance,

(b) give the song a grumbly, distorted, vampy riff which makes it feel busier

and more insistent, if not outright

aggressive, (c) have George deliver the message in an almost

wartime-proclamation tone, without the slightest hint of humor contained in

Chuck’s original delivery. So you could think of the Beatles’ version as ‘Roll

Over Beethoven With A Ball And Chain’, whereas Chuck does that with more of a

feather-tickle touch. I’ll take both and choose one depending on how pissed

off I feel at this particular time of day.

‘Johnny

B. Goode’ — forget it. Not even Marty McFly does a ‘Johnny B. Goode’-enough to

replace the original version. Not a single artist in the world has ever

managed to come up with a way to steal that song from Chuck. It’s been

imitated, mutated, mutilated (Hendrix played some totally crazyass live

versions), but nobody ever made it more exciting than the combination of

Chuck’s guitar, Chuck’s vocals, and Johnnie Johnson’s barrelhouse blues piano

rolls. If not the sole, then the primary reason for Chuck Berry being put on

Earth was to give us ‘Johnny B. Goode’, and nobody can take it away. Not even

worth discussing.

‘Around

And Around’, the B-side to ‘Johnny B. Goode’, is another matter. Of the two

British Invasion bands who laid their grubby hands on the song — the Animals

and the Stones — I unquestionably select the Stones’ version as definitive,

and I think they annihilated Chuck with their performance. Perhaps he just

did not give it enough attention, being so busy with ‘Johnny’ and all, but

the original is a little underdeveloped: the vocals feel slightly tired, the

piano is stuck too deeply into the background, and while the classic guitar

riff is already there, it feels thin and wimpy. The impression is that the

Stones put more soul and belief in

the song than Chuck did himself, making it their definitive early rock’n’roll

anthem — no wonder they used it to open their famous performance on the

T.A.M.I. Show. Great rock’n’roll performance from all parties involved, but

in the event of a need to score, it’s one less for Chuck and one more for the

British boys.

The

Stones present an equally serious challenge to ‘Carol’, which they also

tightened up and made far more dangerous and ballistic than the original, but

this is the same case as with ‘Roll Over Beethoven’ — one might argue that

they made it a bit too serious,

taking out the goofy humor of Chuck’s story about a guy who has to learn to

dance in order to keep his girl safe from competitors. The best thing about

the song is the exciting, unpredictable dialog between Chuck and his own lead

guitar — echoing each of his vocal lines with a subtle mood twist — but the

clinch here is that Keith Richards totally got that, and made his guitar engage in an equally

meaningful dialog with Jagger’s delivery. (He would explore that dialog even

further when the Stones would seriously slow the song down on their 1969

American tour, as captured on the Ya-Ya’s

album). Ultimately, it’s a tie.

‘Sweet

Little Rock’n’Roller’ probably has its main competitor in Rod Stewart’s 1974

hit version — though I have always preferred his live performance of the song

with the Faces and guest star Keith Richards which, captured on video, is

like the ultimate embodiment of the garishness, flamboyance, narciccism,

drugged-out nonchalance, reckless abandon and total excitement of the glammy

mid-Seventies. The funny thing is that Rod had to change Chuck’s original

lyric of "she’s nine years old

and sweet as she can be" to "nineteen

years old" — apparently, in 1959 it was still possible to sing the song

as if it were really innocently describing the joy of a little girl

discovering the excitement of rock’n’roll music, but in 1974, the sexual

revolution imposed certain rules of its own. Anyway, I’m torn here, but

ultimately ‘Sweet Little Rock’n’Roller’ feels like something that is best

experienced in an exorbitantly inebriated state of mind, so I’m giving the

nod to Stewart, the Faces, Keith, and whoever else was rocking the glamhouse

down with the song in the most decadent years of the Me decade. It almost

feels as if Chuck was seeing far ahead into the future when he wrote about

"five thousand tongues screamin’ more,

more! and about fifteen hundred waitin’ outside the door" —

predicting arena-rock way before it happened.

Next

to this, ‘Almost Grown’ feels almost hush-hushy, a quiet little tale about a

teenage guy who doesn’t really want to do much — just a perfect little

bourgeois anthem for all those kids who don’t

want to break down windows and knock down doors, but would rather just get their

eyes on a little girl (ironically, the backing vocals keep chanting

"night and day, night and day", which is clearly a stylistic

reference to Ray Charles’ ‘The Night Time Is The Right Time’, which goes to

show that even unpretentious, non-rebellious quiet bourgeois kids can still

have their natural urges like everybody else). But unlike something like

‘Anthony Boy’, the song is quite rock’n’roll in essence, catchy, fun, and

memorable — although I can certainly understand why, unlike the previous six,

it was hardly ever covered by anybody of importance, meaning that Chuck wins

by definition through total lack of competition. Night and day.

Finally,

there’s ‘Little Queenie’, possibly the last great classic to come out of

Chuck Berry’s songbook — and one of his most compositionally complex, going

from a sung blues verse to a spoken bridge section before erupting in the

rock’n’roll chorus. Again, it’s a triumphant show of Chuck’s subtle, but

always relevant psychologism as he describes, page by page, all the stages of

inviting an unknown attractive girl to dance — and maybe a little something

extra — and the song is totally made by that quiet, half-spoken bridge

("meanwhile... I was thinkin’... she’s in the mood... no need to break

it...") which finally turns deliberation into decisiveness. This magic

has no equals, although Jerry Lee Lewis, another master of rock’n’roll

suspense (in fact, mood-wise ‘Little Queenie’ shares a lot with ‘Whole Lotta

Shakin’), came pretty close. (So did the Stones on the 1969 tour, though they

also slowed down the song, giving it a wholly different flavor). The almost

desperate guitar breaks at the end of the song are the ultimate kicker — some

of those licks would later end up on the Stones’ cover of ‘Down The Road

Apiece’ — so chalk one more up for Chuck here.

The

one single from 1959 that did not manage to make it onto the album was ‘Back

In The U.S.A.’, coupled with ‘Memphis Tennessee’ — repeating the theme of

«bourgeois contentment» with the former and Chuck’s somewhat creepy fascination

with little kids on the latter. Neither of the two is a particular favorite

of mine, but both are classics all the same, and I’d certainly rather have

the Chuck Berry original of ‘Back In The U.S.A.’, with its sincere giddiness

of realization how lucky one is, after all, to live in a first world country, even despite all of its well-known problems,

to Linda Ronstadt’s cover from the sickly hedonistic year of 1978. As for

‘Memphis Tennessee’... everybody covered it and nobody could ever do anything

interesting with it (though I like the little guitar riff that the Animals appended

to the end of each verse on their version), so, again, consider the original

unsurpassed.

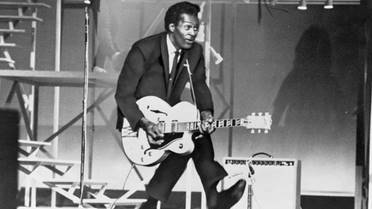

This

concludes our little game which didn’t really have much of a purpose to it other

than to loyally support the greatness of Berry

Is On Top with loads of text. But if you don’t need a load of text to get

the idea that something can be really great, and prefer instead to go with

something ultra-laconic, then how about this: the rock’n’roll of Chuck Berry

is the thickest foundational pillar of 20th century pop culture, and Berry Is On Top has the densest

concentration of Chuck Berry’s rock’n’roll anywhere other than on an

extensive compilation. What else really

needs to be said?..

|

![]()