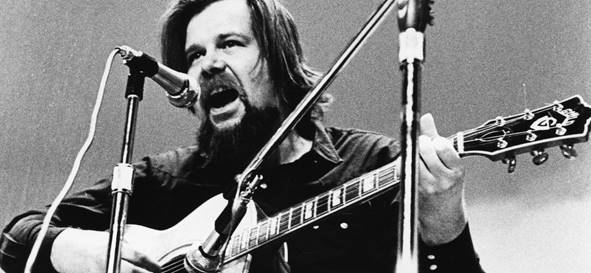

DAVE VAN RONK

![]()

|

Recording years |

Main genre |

Music sample |

|

1958–2001 |

Folk |

Oh, What A Beautiful City

(1959) |

Page

contents:

- Sings Ballads, Blues, And A Spiritual

(1959)

- Van Ronk

Sings (1961)

DAVE VAN RONK

![]()

|

Recording years |

Main genre |

Music sample |

|

1958–2001 |

Folk |

Oh, What A Beautiful City

(1959) |

Page

contents:

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Album

released: May 1959 |

V |

A |

L |

U |

E |

More info: |

||

|

2 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

||||

|

Tracks: 1) Duncan And Brady; 2) Black

Mountain Blues; 3) In The Pines; 4) My Baby’s So Sweet; 5) Twelve Gates To

The City; 6) Winin’ Boy; 7) If You Leave Me Pretty Momma; 8) Backwater Blues;

9) Careless Love; 10) Betty And Dupree; 11) K. C. Moan; 12) Gambler’s Blues;

13) John Henry; 14) How Long. |

||||||||

|

REVIEW

|

||||||||

|

While contemplating oblivion is always a little sad,

it only takes one listen to Van Ronk’s debut album for Folkways Records to

admit that in this case, oblivion is at least understandable, if not entirely

justified. Dave Van Ronk was a passionate and gifted musician and performer,

but he was also a humble soul — and while humility is king when it comes to

general human beings, in case of artists it really places them at a

disadvantage. Already on his first album, recorded after several years of

practice and musical growth, Dave Van Ronk comes across as a skilled guitar

player and an efficient singer with a unique (for his time, at least) vocal

tone — but he writes none of his songs, and does his best to let you

understand that the ones that he covers are being transmitted by him to the general public, rather than

reinterpreted for a modern age. Like most of his Greenwich Village peers, Van Ronk’s

chief inspiration came from the old recordings of the 1920s and early

Depression-era 1930s — the track list on this album specifically indicates

Leadbelly, Reverend Gary Davis, and Bessie Smith as the key figures inspiring

the young Irish performer. His acoustic guitar playing is not intended to

specifically imitate the style of any of the pre-war folk-blues greats — it

owes a lot to the techniques of Mississippi John Hurt and Gary Davis, but, as

a rule, merges them all in Dave’s own technique: nicely syncopated, clean,

steady, precise, unhurrying, pleasant, but not terribly exciting. If there is

one thing that separates his playing from the likes of all those guys, as

well as Big Bill Broonzy and whatever other authentic acoustic-blues black

performers were still playing the revival circuits in the 1950s, it is the

total lack of «flash» and «showmanship»: throughout the album, the man’s

hands remain calm as a cucumber, as if playing guitar for him was like

steering a ship through the reefs (he did spend time in the Merchant Marine,

after all, before settling on the role of folk music artist). This might seem a bit weird next to all those

pictures of Van Ronk’s dishevelled appearance and poetic descriptions such as

Robert Shelton’s likening him to "an

unmade bed strewn with books, record jackets, pipes, empty whiskey bottles,

lines from obscure poets, finger picks, and broken guitar strings",

but appearances can be deceiving. Van Ronk may have looked like an early prototype of Captain Beefheart, and he may

even have had a voice that could sound like an early prototype of Captain

Beefheart, but unlike Captain Beefheart, he seems to have generally been a

sane, rational, «normal» person, just one with relatively little use for

certain basic social conventions of American white society at the time (such

as a primal hatred for «socialism», whatever that term could mean for

anybody). And more than anything, that type of sanity is well reflected in

his music — all these covers sound professional, sincere, imbued with

feeling, and... just a tad boring. The key element here, in 1959, was not so much Van

Ronk’s guitar playing as his voice. Gruff, nasal, croaky, yet at the same

time highly melodic, it was the most «earthy» Greenwich Village could ever

get — Pete Seeger and the entire Kingston Trio sounded like Toddlerville next

to this guy with his howling and wheezing. Of course, in his own turn Van

Ronk would sound like a toddler next to the likes of Blind Willie Johnson or

Charley Patton; but in 1959, Blind Willie Johnson and Charley Patton were

dead, and those of their African-American peers who were still alive and

vocally comparable did not bother to set up residence in Greenwich Village

(though a few younger people did, like Odetta). To many in New York City,

Dave Van Ronk was as close as you could get to actually hearing the true

spirit of these old songs — including Dylan, whose vocal style on his early

acoustic records is very much influenced by Van Ronk, at least through the

very idea that you don’t necessarily have to have a «pretty» voice to be a

folk singer. In retrospect, however, it is difficult not to

acknowledge that an album like this was far more important at a certain place

and in a certain time than it ever could be anywhere and anytime else. While

all the recordings sound pleasant on their own, I made an effort to

specifically play some of them back-to-back with the earlier tracks they were

based on, and in almost every case, Van Ronk... well, not so much «loses» to

the original, but rather just fails to demonstrate what makes his own

interpretation worth being treasured separately. Thus, the lone «spiritual»

of this album — ‘Oh, What A Beautiful City’ — follows the classic Rev. Gary

Davis recording from 1935, which is more engaging musically (reflecting

Davis’ «piano-like» style of playing the guitar) and more moving vocally; Van

Ronk drastically simplifies the melody and leaves the religious ecstasy of

the Reverend’s performance without, so it seems to me, managing to preserve

the pain and suffering reflected in the performance. The latter choice may

have been conscious, because for Dave, sincerity and honesty was key, and he

could not imitate what he did not feel himself; but this, of course, ends up

somewhat eviscerating the purpose of the song. The same goes for ‘Gambler’s Blues’, otherwise known

as ‘St. James’ Infirmary’, a song that has been covered by just about anybody

in the business, but very rarely done just right. Of all the versions I know,

Van Ronk’s stands closest to Jimmie Rodgers’ cover from 1932, and while

Jimmie’s voice was never as «earthy» as Dave’s, his soft, trembling,

quasi-weeping high pitch delivery emphasized the tragedy of the song’s lyrics

far sharper than Van Ronk’s performance. It is almost ironic, since Rodgers’

vocalization is more theatrical and manneristic, while Dave tries hard to

imitate the realistic grittiness of a wasted barroom client — yet there is

something here that makes me want to give poor Jimmie a hug, while at the

same time moving my chair away from Van Ronk’s spot, just for safety reasons. Perhaps the only one of those old performers against

whom Dave can more or less hold his own is Leadbelly. Unlike Gary Davis or

Mississippi John Hurt, Leadbelly was not a great or particularly idiosyncratic

guitar player, and his singing was more like an entertaining storyteller’s

than a passionate artist’s, which gives Dave a chance to steal away a song or

two from Huddie Ledbetter’s vast repertoire. His ‘John Henry’, for instance,

is delivered with more playing and singing frenzy than Leadbelly ever thought

necessary for the song, which is fairly consistent with the song’s

traditional narrative of Man Vs. Machine; more importantly, both Leadbelly

and Big Bill Broonzy sing the song rather playfully, with the tragedy implied

by the narrative rather than conveyed by the singing and playing, whereas

Dave goes about it bluntly and openly. Likewise, his rendition of the creepy

ballad ‘In The Pines’ (a.k.a. ‘Where Did You Sleep Last Night?’) is, at least

on the surface, more lyrical and caring than Leadbelly’s — although cynical

tongues might add that he is just doing that to make the material more

palatable for his white audiences. But then again, what alternatives could

one really have in the middle of Greenwich Village? Move to the Delta? All in all, I won’t lie and pretend that the album

holds that much more than just historical significance for me. But it is pleasant to listen to if you are

into folk-blues music at all, and it is

interesting to compare these interpretations with the sources, just to see

the evolution of the material from rowdy pre-war African-American context to

rowdy post-war white socialist college student context in that brief time

window before it either got

commercialized à la Peter, Paul & Mary model or evolved into

something completely different, like Bob Dylan or Phil Ochs. I dare say,

though, that reading Dave Van Ronk’s autobiography (The Mayor Of MacDougal Street) is probably a more fascinating way

to plunge yourself into the reality of those epochal times than just

listening to his music. |

||||||||

![]()

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Album

released: July 1961 |

V |

A |

L |

U |

E |

More info: |

||

|

2 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

||||

|

Tracks: 1) Bed Bug Blues; 2) Yas-Yas-Yas;

3) Please See That My Grave Is Kept Clean; 4) Tell Old Bill; 5) Georgie And

The IRT; 6) Hesitation Blues; 7) Hootchy Kootchy Man; 8) Sweet Substitute; 9)

Dink’s Song; 10) River Come Down; 11) Just A Closer Walk With Thee; 12) Come

Back Baby; 13) Spike Driver’s Moan; 14) Standing By My Window; 15) Willie The

Weeper. |

||||||||

|

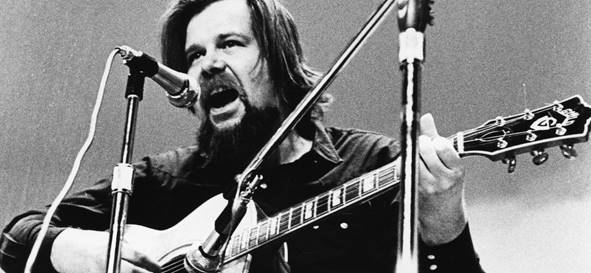

REVIEW Dave’s

second full-length album for Folkways (re-released several years later as Dave Van Ronk Sings The Blues,

perhaps to emphasize the fact that there are no «ballads» or «spirituals»

this time) changes very little about the formula established on his first

one, so coming up with any additional generalizations would be quite a chore.

It does not expand on Van Ronk’s stylistic, philosophical, or vocal range,

and his acoustic guitar playing is even less interesting here than it used to

be. Switching back and forth between the two records, I can only notice that

this one tends to be slightly less reverential and a tad more humorous: for

instance, the first LP had no bona fide «joke blues» numbers such as

‘Yas-Yas-Yas’, a «hokum» dance-blues tune that Dave allegedly snatched from a

recording by Blind Blake & The Royal Victoria Hotel Calypsos made in 1951

(note: this is a different Blind

Blake from the classic virtuoso blues guitarist Blind Blake who died in 1934)

— "Mama bought a chicken / She

thought it was a duck / Put it on the table with its legs sticking up..."

(Not-so-insignificant trivia bit: here be another small link between Dave Van

Ronk and Captain Beefheart, who would later make lyrical references to

‘Yas-Yas-Yas’ in his own ‘Old Fart At Play’ on Trout Mask Replica). Occasional touches like these make the

atmosphere lighter and, in a way, more authentic, but whether it’s an

objective plus remains unclear. |

||||||||

|

We continue, of course, to see just how strong Dave’s

influence was on Dylan, who would record his own version of Blind Lemon Jefferson’s

‘Please See That My Grave Is Kept Clean’ on his debut album — largely following

in the steps of Van Ronk rather than Blind Lemon himself. There, however,

lies the rub, as you can easily witness yourself if you line up all three

versions and listen to them in chronological succession. What Van Ronk does,

basically, is just cover Blind Lemon: he plays a similar guitar pattern, uses

the same types of vocal modulation and strives to replicate the original

atmosphere. At the time, this was regarded as a virtue: rough, unadorned

guitar playing and a creaky, croaky, earthy voice as opposed to the

stereotypical «angelization» of old folk and blues by the average white

performer in Greenwich Village, not to mention the fact that original

recordings by Blind Lemon were not always easily accessible even to those who

did hunt for them, let alone the casual listener who would only scoop up

whatever was at hand — like a brand new Dave Van Ronk LP from the Folkways

label in your nearby record store. Today, though, when time has flattened and nivelated

the historical difference between 1928 and 1961, the historical relevance of Blind

Lemon Jefferson has remained stable, while that of Van Ronk’s covers of his

material has quite sorely decreased. Dave struggles to soak in the spirit of

the original Delta performer, doing good, but not great; the genius of Dylan

was in that he’d only used that spirit as a base influence, injecting it with

his own brand of adrenaline, taking the idea of «you can sing in a weird voice

and play weird guitar, like the black dudes did before the war» but effectively

leaving out the second part, because, well, a white dude can hardly play and

sing like a black dude anyway... well, maybe a white dude like Dave Van Ronk

could have some knack for that, but certainly not a white dude like Bobbie Zimmerman.

Certainly you can feel Van Ronk riding the same vibe as Blind Lemon,

cherishing and respecting the original feels, yet it is difficult to get rid

of the sensation that the general idea was something like «well, here’s a

dusted-off oldie for the kids of today who can finally listen to it without

all those annoying crackles, hisses, and pops». Van Ronk’s artistic strength is felt much better on

those numbers which do not have a

classic Delta-style prototype; a classic example here is ‘Dink’s Song’, a.k.a.

‘Fare Thee Well (My Honey)’, whose origins stretch even further back than ‘See

That My Grave Is Kept Clean’ (it was allegedly first recorded by John Lomax

in 1904 from a woman called ‘Dink’ in a Texas work camp, although the

recording does not seem to have survived). After the song was published, it had

been officially recorded by a number of performers — Josh White, Harry Belafonte,

Pete Seeger — but mostly with a jazzy or an «angelic-folk» vibe, so Van Ronk’s

interpretation, with the man singing at the top range of his croaky voice, gave

the tune lots of extra power and soul, becoming the definitive version and one

of Van Ronk’s signature performances (no wonder Oscar Isaac gets to sing a good two

minutes of it for his impersonation of Van Ronk in Inside Llewyn Davis). Although both melodically and lyrically, ‘Dink’s

Song’ is just as much a classic blues number as anything else, it also has certain

overtones going back to medieval ballads (even the refrain of "fare thee well my honey, fare thee well"

hardly has any African-American linguistic properties), and Van Ronk is the

perfect guy to roughen and toughen up this mix of sources, especially when

compared to, for instance, the first commercial performance of the song by Libby Holman. Funny enough, Dylan covered ‘Dink’s Song’, too — you

can hear a five-minute long version from the «Minnesota Hotel Tape» on the No Direction Home soundtrack — and he

also tried to give the tune a different vibe, playing a much more energetic,

almost danceable guitar pattern and injecting a bit of the usual Dylan irony

and grumpiness in the vocal performance (note, too, how he displaces the

accent from Van Ronk’s "fare thee

welllllllll..." onto "fare

thee weeeeeeeell...", which makes the refrain a bit more «cackling»

than «desperate»). However, in this case I think that Dylan’s version does

not work: Van Ronk stays true to the song’s bitter message of abandonment and

deceit, while Bob tries to push it into the realm of the cynical, and fails —

to do that properly, he’d need to start writing his own lyrics. Small wonder,

then, that ‘Dink’s Song’ did not ultimately make it into Bob’s regular

repertoire. Unfortunately, there are many more numbers similar

in their relative uselessness to ‘See That My Grave Is Kept Clean’ on Van Ronk Sings, than tracks similar

in their usefulness to ‘Dink’s Song’. Try as he might, Dave cannot generate

the same menace as Muddy Waters on his cover of ‘Hoochie Coochie Man’ (even

when throwing on an extra verse from ‘I’m Ready’ for good measure), or

outperform Sister Rosetta Tharpe on ‘Just A Closer Walk With Thee’, or make

slow blues numbers like ‘Come Back Baby’ as engaging as Ray Charles. All of

that stuff is decent enough to be heard on a nice, relaxing summer evening in

your local coffee shop, but that’s about it. You know something’s not quite

right when the song that draws your attention the most is a hilarious

vaudeville number about an addicted chimney sweeper (‘Willie The Weeper’,

featuring one of the seventy million different sets of lyrics about Willie’s

adventures in the sweet world of opiates), just because it’s fast, jumpy,

aggressive, and featuring the singer at his most guttural and «all-out there». It might have worked out better if Dave cared to

imbue more of that «modern sensitivity» into the recordings, but the only

number that actually does that is the black humor-tinged ‘Georgie And The IRT’,

a straightahead parody on The Carter Family’s ‘Engine 143’ co-written

by Dave with his friend Lawrence Block, a fairly special guy who used various

pseudonyms to write naughty erotic novels about the covert sides of life in Greenwich

Village ("Anita

was a virgin — till the hipsters got hold of her!"). Dave and Lawrence’s

parody updates the original setting of the song, about an unfortunate

engineer who ran his train into the rocks back in 1890, to modern times, with

the appropriate lyrical changes from "The very last words poor Georgie said was nearer, my God, to Thee"

to "The very last words that

Georgie said were ‘Screw the IRT!’" as the protagonist now has to

die in a hilarious accident caused by peak hour pressure. Granted, the song,

which Dave here performs as a duet with the somewhat notorious 12-string

guitarist Dick Rosmini, is nothing but a joke, but it’s a pretty damn funny

joke for the times, not to mention the historical interest (who even

remembers, in this day and age, the Interborough Rapid Transit as the

original designation of one of New York’s private subway operators?). Irreverence and humor are indeed a bit of a saving

grace for the record, from the old-timey approach on ‘Yas-Yas-Yas’ to the

contemporary update on ‘Georgie’, but modernization of tradition rarely rests

upon humor alone — and if it did for Dave, he’d turn into a vaudeville act,

which was hardly a coveted goal — yet we still don’t really see Van Ronk

predicting the rise of even Phil Ochs, let alone Bob Dylan. To me, about half

of the album, particularly when Dave is singing straightforward 12-bar blues,

is flat-out boring; the other half, ranging from a tiny bunch of soulful

highlights like ‘Dink’s Song’ to the joke numbers, is what might be called «promising»,

but still not exactly breathtaking. One might even regard this as a bit of

the proverbial «sophomore slump», given that Dave’s mission and image had

been firmly established on the first record, and this one offers relatively

few advances from it; but it’s difficult in general to analyze Van Ronk’s

career in terms of highs and lows, since the man always kept his ambitiousness

in check, never striving to be a star and never pretending that he himself

really had a lot more to say that hadn’t already been said before. Ah, if

this kind of humility were considered top virtue in the world of popular

music... she’d be my Grandpa, I guess. |

||||||||

![]()