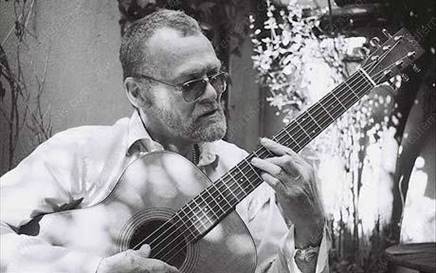

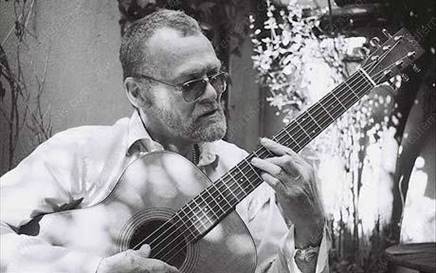

DAVEY GRAHAM

![]()

|

Recording years |

Main genre |

Music sample |

|

1962–2008 |

Folk |

Take Five (1963) |

Page

contents:

- The

Guitar Player (1963)

- Folk Roots, New

Routes (1964)

DAVEY GRAHAM

![]()

|

Recording years |

Main genre |

Music sample |

|

1962–2008 |

Folk |

Take Five (1963) |

Page

contents:

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Album

released: 1963 |

V |

A |

L |

U |

E |

More info: |

||

|

4 |

4 |

3 |

5 |

3 |

||||

|

Tracks: 1) Don’t Stop The Carnival; 2)

Sermonette; 3) Take Five; 4) How Long, How

Long Blues; 5) Sunset Eyes; 6) Cry Me A River; 7) The Ruby And The Pearl; 8)

Buffalo; 9) Exodus; 10) Yellow Bird; 11) Blues For

Betty; 12) Hallelujah, I Love Her So. |

||||||||

|

REVIEW

First

and foremost, the album is called The

Guitar Player, not The Folk

Musician or The People’s Artist

or whatever, and if there is one particular thing that it chronicles, it is

pure, sincere, and loyal love between a musician and his instrument,

regardless of any specific genre or style barriers. In an era where most

people’s idea of somebody playing an acoustic guitar was Big Bill Broonzy, or

Pete Seeger, or at least Lonnie Donegan (over on this side of the Atlantic),

seeing somebody outside the highly specialized world of classical guitar use

the acoustic as a self-sufficient means in itself was a rare marvel indeed, and

many times a rare marvel if it were used with such total unpredictability and

freedom. |

||||||||

|

Graham was not a technical virtuoso, and his aim

with these instrumentals is never to dazzle the listener with lightning-speed

playing, impossible chord combinations, or any special tricks. Instead, his

aim is to demonstrate the emotional power of acoustic guitar and, if

possible, draw your complete attention to it. This is already evident in his

first well-known composition, ‘Angi’ (= ‘Angie’, ‘Anji’), which is not on

this record but was released on a three-song EP from 1962 (a re-recorded

version from the 1970s is appended to the CD edition of Guitar Player as a bonus) — a short, repetitive piece which may

not seem like much to the modern jaded listener, but back in the 1960s was

the hottest thing around, most notably covered by Bert Jansch and then by

Simon & Garfunkel (who actually thought it was written by Bert). Its bit of mystique is probably rooted in that

it is even unclear which genre it is. Blues? Jazz? Folk? The rhythm seems

jazzy, the main guitar hook is bluesy, yet the overall mood is closer to dark

folk. Proper musicological analysis will give you a formal explanation, but

the heart of the matter is that ‘Angi’ is Davy Graham in a nutshell — two

minutes of lovely acoustic guitar which does not subscribe to any specific

line of convention. On the album itself, Graham is joined by notorious

session drummer Bobby Graham (ironically, no relation) — one of the few

players, apparently, who could keep up with him in all of his genre-defying

endeavors — and nobody else. About half of the numbers, as I already said,

are jazz covers, and these folkified renditions of Cannonball Adderley’s

‘Sermonette’ and Teddy Edwards’ ‘Sunset Eyes’ go a long way towards

demonstrating the shared musical roots of sophisticated jazz and hillbilly

dance music — though, admittedly, Davy can also hit upon trickier tempos and

come up with something more exquisite and less accessible, for instance, when

transcribing Brubeck’s ‘Take Five’: reduced to a barebones two-minute long

musical skeleton, the composition becomes melancholic and meditative even if

it still retains the speed of the original. But he is actually even more

inventive when it comes to shmaltzy material — thus, ‘The Ruby & The Pearl’,

a song originally recorded as a slow, sappy, heavily orchestrated ballad by

Nat King Cole, is reinvented as a Mexican number (replete with Bobby clacking

those castanets), probably not very impressive on its own but quite hilarious

when played next to the original, just for the sake of comparison. At the same time, Davy gives us his take on the old

urban blues tradition (Leroy Carr’s ‘How Long, How Long Blues’, played with

all the confidence of a Delta player, if not with the actual spirit), saves a

spot for classic Ray Charles-style R&B (‘Hallelujah, I Love Her So’), and

dares to include one of his own compositions — ‘Blues For Betty’, which might

seem like an ordinary blues shuffle at first, but dig in closer and you will

notice Davey throwing in little classical flourishes and bits of dissonance,

and generally going unpredictable places which probably would not be on the

minds of too many traditional bluesmen. It’s all done modestly and completely

without flashiness, so it might be hard to spot — and it is this very lack of

flash that prevented Davy Graham from ever becoming a household name; but it

also rewards patient and attentive listeners, though I confess that I

personally do not have that much

patience and attention to become a full-on admirer as some fans do, probably

because this relatively «academic» approach to the guitar is not my favorite

kind of approach. But then again, this is at least «inventive academic» as

opposed to «conservative academic», graced by the addition of intrigue and unpredictability

rather than religious purism. An important detail is that, back at the time,

Graham’s recordings must have sounded particularly fresh and unusual to

listeners and musicians alike due to his adoption of the D-A-D-G-A-D tuning,

which is now sometimes nicknamed «Celtic tuning» but which he himself

apparently nicked from Moroccan music during his stay in the country. To the

modern listener, this is such a standard practice, employed by most players

of Celtic folk or Celtic-inspired pop/rock music (‘Kashmir’, etc.), that it

would be hard to believe this kind of sound was not heard from acoustic

guitar players before Graham — but apparently, it is just so. However, if I

am not mistaken, only a few tracks on this particular album are in that

tuning; the most notable example from Davy’s early years is his

Eastern-influenced rendition of ‘She Moved Through The Fair’, which is not

included here. The most common CD release of the album on the

market is a little bizarre, adding half an hour’s worth of excellent bonus

tracks that make an even better showcase for Davy’s amazing genre range — but

all of these tracks are from much later periods (a brief live rendition of

‘Anji’ from 1976, and even more live performances that date back to the

1990s): the nearly eight-minute long ‘She Moved Thru’ The Bizarre / Blue

Raga’, as you can probably guess from the title already, is a fascinating

juxtaposition of British folk and Eastern raga, but I am not exactly sure

what this track, recorded in 1997, has to do in this particular location —

and why they could not have included the rare original recording of ‘She

Moved Through The Fair’ instead. |

||||||||

![]()

|

|

(w. Shirley Collins) |

|

||||||

|

Album

released: March 1964 |

V |

A |

L |

U |

E |

More info: |

||

|

3 |

4 |

3 |

5 |

3 |

||||

|

Tracks: 1) Nottamun Town; 2) Proud

Maisrie; 3) The Cherry Tree Carol; 4) Blue Monk; 5) Hares On The Mountain; 6)

Reynardine; 7) Pretty Saro; 8) Rif Mountain; 9) Jane, Jane; 10) Love Is

Pleasin’; 11) Boll Weevil, Holler; 12) Hori Horo; 13) Bad Girl; 14) Lord

Gregory; 15) Grooveyard; 16) Dearest Dear. |

||||||||

|

REVIEW

|

||||||||

|

That said, Shirley Collins was not really some sort

of stiff-collared Victorian prude who would hold up her academically

conservative treatment of folk legacy with religious fervor: every once in a

while she would agree to collaborate with various musicians who had their own

agenda (such as Ashley Hutchings’ Albion Band, for instance), acting as an

anchor of stability in a potentially (though, as a rule, quite modestly)

experimental setting. In such collaborative projects she actually becomes

somewhat more interesting herself — which is why this album, pairing her up

with one of folk music’s biggest iconoclasts, is unquestionably one of the

most intriguing, if not the most intriguing,

steps in her career. But see, I have actually almost allowed myself to

fall into the usual trap: the majority of retro reviews of this poorly

remembered, but well-respected classic LP tend to concentrate on Shirley

Collins, just briefly commenting on Graham’s work as her sideman. This is not

something that would probably happen in the classical world (I have a hard

time imagining how a review of, say, a recording of Schubert’s Winterreise could focus almost

exclusively on the singer and forget about the pianist next to him, especially

if the pianist were of the caliber of Sviatoslav Richter), but it may be

generally excused for the world of traditional folk music, where words and

the way they are delivered have always been treasured over the generic and

usually predictable music patterns to which they were set. The funny thing is that with the aptly titled Folk Roots, New Routes this trope is

inverted: a single serious listen will clearly reveal that Davy is firmly in

charge of the proceedings, while Shirley is essentially a sidekick. First,

there is the little matter of the setlist — which does, it is true, to a

large degree consist of (largely untraditional) recordings of traditional

folk music; but it also happens to contain Graham’s solo acoustic guitar

arrangements of Thelonious Monk’s ‘Blue Monk’ (!) and an obscure composition

called ‘Grooveyard’, by jazz pianist Bobby Timmons. The ‘Blue Monk’ cover is

particularly stunning in how neatly it captures the groove of Monk’s main

theme, and then seamlessly transforms it into what could have been mistaken

for a little creative improvisation from an old Delta bluesman — at the same

time preserving the spirit of Monk’s weird harmony experiments at his piano.

The big question, however, is — what exactly is a thing like that doing on an

album of vocal folk covers? Is it merely

to provide a grateful (or gratuitous) spotlight for the accompanying

musician, or is it to accommodate some sort of grand vision that goes way

beyond loyal coverage of royal heritage? Now to answer this

question, we must cast a wider net and look at the actual covers. A good

introductory example would be ‘Pretty Saro’, a long-forgotten melancholic

British ballad allegedly revived in the Appalaches, and then re-imported by

Shirley into her own native country — except that Graham seems to ironically

misread the title as ‘Pretty Sarod’,

and proceed to reinvent it as a cross between a Western ballad and an Indian

raga, while Shirley nonchalantly delivers the lyrics precisely the way they

are supposed to be delivered. This musical equivalent of an interracial

marriage is fresh and lovely, with the slow and meditative Eastern pulse of

the arrangement agreeing surprisingly well with the brooding spirit of the

old song itself; and as if to strengthen his synthetic point, Graham

immediately follows it with ‘Rif Mountain’, his own instrumental composition

drawing upon the musical experience he’d picked up during his stay in Morocco

with the local musicians. Everything’s pretty Moroccan about it, except it’s

all played on a regular acoustic guitar — and if you enjoy that sort of

approach on your Jimmy Page records, there is nothing wrong to check out

Jimmy’s foremost inspiration, who did it earlier and with just as much, if

not more, verve and professionalism. On other tracks, Graham largely prefers to stay

within more Western territory, but this often means taking Western quite literally. Thus, the

arrangement for ‘Proud Maisrie’ (an old Scottish ballad also known as ‘The

Gardener Child’) seems to follow a regular old folk chord progression at

first, but then Graham begins to embellish the melody with bluesy phrasing

copped from Robert Johnson’s records, creating rather jarring dissonant

impressions that break up the lullaby-like monotony which so often plagues

stereotypical folk ballads. Right after that comes ‘The Cherry Tree Carol’,

for which Davy (for once!) trades in his guitar for a banjo, sitting his ass

down on the porch of his winter home in the mountains and playing his

instrument with a certain confidently amateurish flair, as opposed to the

aura of deep experience which usually flows from his guitar performances. This could be continued and expanded to almost each

of these tracks — it’s just that at this point, a certain amount of technical

and musicological knowledge vastly exceeding mine would be needed to disclose

all the nifty secrets of this record. But do believe me when I say that in

order to be charmed and wooed by its unusualness, all you have to do in

advance is sit down with a «generic» Shirley Collins record on which she

plays the guitar herself: the difference will hit you like a ton of bricks. I

even feel a bit sorry for Shirley: she always does her job well — but there

is a goddamn reason why Graham actually gets to have three solo numbers on

this collaborative record, while she only performs one number (‘Lord

Gregory’) a cappella. It is quite transparently clear who is the «folk roots»

and who is the «new routes» on this album — although, in the end, it is

precisely the combination of the two (my favorite sort of combination!) which

makes the whole experience so admirable. If it weren’t for the extremely

limited appeal of the folk genre as a whole, the record could have become a

major classic: as it is, it remains more of a cult favorite for the select

few, but then I guess that this is precisely how the select few would like it

to stay, and I sort of get their point. |

||||||||

![]()