|

But

a much more important dividing line than simply a radical line-up reshuffle

separates the «New Drifters» from the old ones. The times, after all, were

a-changin’. The age of doo-wop and doo-wop-style R&B was coming to an

end. Those cozy, round-the-fireplace sessions with little backing bands and a

bunch of choirboy pals huddling around the mike? Who really needed that style

with all the improvements in recording technology, now that you could have

epic, bombastic sounds blaring out of your brand new stereo equipment? The

Fifties, with their rough, crude, «homebrewn» sounds were on the way out;

enter the early Sixties, a time of swooping, overwhelming sentiment, lilting

romance, and overall cleanliness. The music business was killing two birds

with one stone at the same time — it was luring in waves of new customers by

offering them sonic brilliance on a level never heard before, and it was also taming and pacifying

said customers’ spirits by subtly «cleaning up» the wild energy and sexual

aggression of last decade’s R&B explosion. In this department, the

African-American scene was no different than the white artists of the time: everybody got a haircut and a shave.

For

about a year, the «New Drifters» kept away (or were kept away) from the

studio as they focused on live performance, struggling to get audiences to

come to terms with the fact that old Drifters’ material was performed by

completely new guys (actually, I have no idea if their setlists in 1958–1959

consisted primarily of songs by the original Drifters or something else; all

I know is that there had been reports of the band frequently booed off the

stage for being impostors). But when they did eventually earn the trust of

their overlords and entered the studio on March 6, 1959 — this time, under

the supervision of none other than the illustrious Jerry Leiber and Mike

Stoller — they emerged with ‘There Goes My Baby’, and pop music would never

be the same again, for better or worse.

‘There Goes My Baby’ was supposedly written by Ben

E. King himself, although George Treadwell (the original manager of the old

Drifters) and Lover Patterson (the original manager of the new Drifters) both

took co-credit because might makes right. As musicological sources tell us,

the arrangement shapes the song into an imitation of the Brazilian

baião (courtesy of Leiber & Stoller, who were big fans of Latin

music at the time), though my ears have to struggle to recognize that,

because the rhythmic skeleton of the song is buried deep in the mix under the

soaring strings and Ben’s lead vocal — the loudest, liveliest, and most

operatic that any of the «Original Drifters»’ music had ever been. Good-bye,

crooning and doo-wop; hello, new R&B equivalent of a Luciano Pavarotti

(okay, more like Tito Gobbi, since Pavarotti was still more or less a nobody

back in 1959).

My own feelings about the song, and the style in

particular, are conflicting. The importance and influence of ‘There Goes My

Baby’ cannot be denied — as is the simple fact that it rose all the way to #2

on the general Billboard charts,

making the Drifters almost overnight into a national, if not worldwide,

phenomenon and giving the R&B market of Atlantic Records an audience far,

far exceeding its usual audience of African-American listeners (thus also,

perhaps, paving the way for future successes of Motown Records). But it is

also quite clear that in order to achieve that success, some values had to be

seriously compromised: in fact, other than certain singing overtones from Ben

and the dynamics between him and the other Drifters on backing vocals, there

is very little, if anything, that is distinctly «black» about the song. The

lyrics are typical white schoolboy tripe ("I broke her heart and made her cry / Now I’m alone, what can I do?"

— jeez, this looks really awful

when I just put it down in writing like this), the overpowering strings owe

their existence to schmaltz, and the Brazilian rhythmic pattern is... well,

Brazilian. Rumor has it that Jerry Wexler, the number two guy at Atlantic

after Ahmet Ertegun at the time, actually hated the song and even tried to

keep it off the market — and I can easily understand why.

On the other hand, I can also understand reports

of how people on the streets and inside the jukebox diners would all stop

their activities and wonder where that amazing sound comes from when they

first heard ‘There Goes My Baby’ blasting out of the speakers. That’s one

hell of a big sound Leiber &

Stoller got out of their singers and musicians: the rhythm section, with all

the reverb and mixing preferences, feels like a steady earthquake going on,

while the orchestra saunters on top of it like a kick-ass thunderstorm and

the singer strains his powerful voice to the max. Interestingly, the

arrangement is actually quite minimalistic when you come to think about it —

bass, percussion, strings, vocals, I am not even hearing any guitars,

keyboards, or brass at all — but it produces an absolutely bombastic

impression, and you can certainly see where Phil Spector (who would soon

begin his production career as an apprentice to Leiber & Stoller) got his

own style from, as did pretty much everyone else opting for that kind of

wall-of-sound. Special honorable mention should go to the cello part entering

at about 1:00 into the song — giving it an even gutsier feel (you can always

tell a good string arrangement by looking at whether it gives cellos

precedent over violins at any given point).

With ‘There Goes My Baby’ completely turning

tables over the (New) Drifters’ fortune, they quickly followed it up with

‘Dance With Me’, written this time by Leiber and Stoller themselves (under

the pseudonym of «Lewis Lebish and Elmo Glick»). It was also formula, but a

little different, and the differences were not particularly beneficial. There

was no drama this time — only pure sappy romanticism — and although there

were also Latin rhythmic influences, strings, and plenty of whoah-whoahs from

Ben, supported by his loyal backing henchmen, its mood was pure escapist

Prince Charming-meets-Cinderella-at-the-ball vaudeville. (Violins, violins,

and more violins, of course, no cellos to sour the mood). Listening to the

tune somehow always ends up bringing the Beatles’ ‘I’m Happy Just To Dance

With You’ on my mind — that one almost seems like an homage to this one, with

precisely the same emotional message, but there is a saving element of

toughness in the Beatles’ song (those crackling electric guitar rhythm chords

alone are enough to do the trick), whereas the Drifters’ song does not really

begin to engage me until the coda, when Ben briefly lets himself go with all

the whoah-whoahs. Amusingly, the song did

fare a little worse with listeners, only making it as high as #15 on the

general charts — by all accounts, still a major achievement for an R&B

band, but clearly indicating that there was no «stun effect» this time as

there had been with ‘There Goes My Baby’.

Undaunted, Leiber & Stoller plowed on, taking

a composition written by Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman, the honorary pair of

songwriters at Elvis’ court — they had already donated some of their stuff

for the Drifters’ B-sides, but ‘This Magic Moment’ was the first of their

A-sides. The song again follows the «happy magic» emotional sway of ‘Dance

With Me’ rather than the dramatic angle of ‘There Goes My Baby’, and again exploits Latin dance rhythms,

but this time at least there is a bit more creativity. The opening strings

create a stereotypical «whirlwind of passion», clearly simulating the

proverbial butterflies-in-stomach feel, and there is a nice intimate segment

in the "sweeter than wine, softer

than the summer night" bridge, when the full-scale arrangement is

replaced by just Ben and quiet bits of Spanish guitar, as if we are

temporarily transferred to an under-the-balcony setting. Again, I am not a

big fan of the song, but it is hard not to appreciate the skill and

intelligence that went into the arrangement. However, its chart showing was

just a wee bit lower than ‘Dance With Me’, indicating that perhaps the new

formula was wearing a bit thin after all.

So they did try to change it a bit. Released in

May or June 1960, ‘Lonely Winds’, although also written by Pomus and Shuman, returned

to a more «traditional» R&B basis, temporarily ditching Latin influences

and turning to a slightly (though only slightly) grittier mood, as King once

again sang about separation and loneliness rather than mushy-mushy and the

strings were largely replaced by brass and gospel organ, except for the

instrumental break where they entered with an almost playful, catchy, frisky,

country-western-influenced melody. Alas, it was too late: public admiration

for that style had quite dissipated, and the song did not make enough

commercial impact to even be included into the Atlantic Rhythm & Blues

boxset years later. Too bad. I recognize that it owes a lot to ‘My Bonnie’

(particularly the bring my, bring my

little bitty girly on home to me chorus), and that it is formally

«regressive» as opposed to the giant hits surrounding it, but I feel like it

has more of that «honest soul» inside that chorus than any of the New

Drifters’ or, for that matter, Ben E. King’s solo starry-eyed Spanish

serenades. At any rate, if you’re looking down history lane, do not forget

about it.

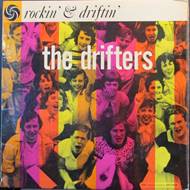

Still, even if technically it all seemed to be

slowly going downhill for the Drifters again, with each new single after the

explosion of ‘There Goes My Baby’ faring poorer and poorer, the explosion was

so massive and caused so many ripples that Atlantic felt it worthwhile to

reward their biggest-selling group of the year with an LP release, unimaginatively

and, of course, widely inaccurately called The Drifters’ Greatest Hits.

Because of this, I almost missed the album at first in my own retrospective,

believing it to be just a best-of compilation through the years; in reality,

it is a rather faithful assembly of most of the stuff they’d recorded with

Ben — all four of the aforementioned A-sides together with their respective

B-sides. Padding out the album was a fresh recording of the 1955 popular song

‘Suddenly There’s A Valley’ (it would later make the B-side of ‘I Count The

Tears’ at the end of 1960), and three outtakes for which Atlantic dug into

the vaults, extracting them from the dust of the interim years of 1956–1957.

Of the B-sides, ‘Oh My Love’ is rather generic

doo-wop; ‘(If You Cry) True Love, True Love’, featuring the falsetto of new

temporary member Johnny Lee Williams, is an even mushier and sappier serenade

than anything discussed before; ‘Hey Senorita’ is the band’s lone attempt at

«Latin rock’n’roll» sounding a bit like the Drifters covering Bo Diddley

covering Ritchie Valens — not even as horrendous as that might seem, but

fully out of character for the band and superfluous (if you want dirty /

gritty / sweaty like that, just go straight to the sources); but I do like

‘Baltimore’, with Charlie Thomas taking lead and the entire band showing that

if they really want, they can be almost as funny and clownish as the

Coasters. Funny that it was the B-side of ‘Magic Moment’, giving audiences a

taste of two completely different sides of the band. That said, of course,

it’s just a silly little novelty number.

And, as usual, it feels weird and bizarre to have

those oldies from 1956 mixed with the new songs — mainly to show just how

deeply the music had changed in those few years. Songs like ‘Sadie My Lady’,

a hybrid of jump-blues and doo-wop, still with Johnny Moore at the helm, are

so sonically mid-Fifties that they feel decidedly dinosaurish next to the

King-era hits; yet they also remind of that roughness and immediacy that was,

unfortunately, lost for good with the transition to new production and

arrangement values, and hearing both this song and the even more good-time

«pub-R&B» of ‘Honky Tonky’ almost makes me greet these forgotten guys

like dear old friends. Honestly, I tip my imaginary hat to all of those Greatest

Hits, but I feel that if this were a completely personal desert island

choice, I would ultimately trade in ‘There Goes My Baby’, ‘Dance With Me’, and ‘This Magic Moment’ — all three of

them in one bundle — for the merry, life-asserting stomp of "honky tonk rock’n’roll", because

I like it when the boys just let their hair down and allow themselves to have

fun.

Overall, I would not go as far as to say that

Leiber & Stoller «sold out» the new Drifters to schmaltz-loving middle-aged

white audiences, but it may be worth noting that none of these big singles,

despite their popularity and everything, were ever picked up by any artists I

care about (‘Dance With Me’ would be covered by the likes of Billy J. Kramer

& The Dakotas, I believe, or Engelbert Humperdinck), as opposed to

McPhatter-era songs or later, swaggier pieces like ‘Under The Boardwalk’ —

apparently, there must have been a

feeling that they were pandering to the white mainstream, which, let’s face

it, would be perfectly expectable around 1959–1960. On the other hand, this

is one complaint that can easily be extended to a lot of soul / «soul-pop» music in the Sixties, or even

transformed into a full-fledged refutation of the entire aesthetics of

classic Motown; walking the thinnest of thin lines here while trying to

decode your gut feelings about what is «honest and true» and what is «slick

and artificial» in this music is a tremendously difficult task. But a fun

one!

|

![]()