|

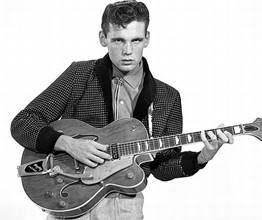

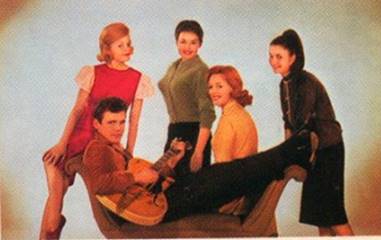

Next came a bit acting part in the teen-and-teacher

drama Because They’re Young, a

movie that was somewhat daring for its time for its mildly daring (for 1960,

probably smashingly daring) depiction

of sexual relations, especially when one considers that the main role was

played by Dick Clark (then again, Dick Clark did have a fully conventional

image, but was very well known for using it to his advantage while promoting

all sorts of unconventional artists). The movie has preserved for us a very

rare piece of footage of a young Duane Eddy playing his guitar on ‘Shazam!’, another

minor hit from the tune smithery of Eddy and Hazlewood, though hardly

original, as it is basically just another yakety-sax oriented country-rock

dance tune without a particularly outstanding hook. Even more lucrative for

Eddy was the title track to the movie, a lushly orchestrated pop ditty

co-written by a bunch of guys including Aaron Schroeder (one of Elvis’

primary composers); I think that Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman later nicked both

the main rhythm and the main twangy riff for their own ‘Little Sister’, which

takes a little effort to notice because atmospherically, ‘Little Sister’ is

gritty and «dangerous» (one of the very few cases where we get to see a

post-Army Elvis actually bare his teeth), whereas ‘Because They’re Young’ has

a celebratory atmosphere throughout, and Eddy merely acts here as the

proverbial «first violin» within the defined limits of a symphonic orchestra.

Stilted as it is, it goes without saying that Duane Eddy’s instrumental

version of ‘Because They’re Young’ is far preferable to the milk-and-honey

vocal version of James Darren from the same year (as featured in the movie),

or the later UK cover by Helen Shapiro — yet at the same time, it is only

with bitter irony that one might be allowed to react to the fact that

‘Because They’re Young’ became the biggest commercial hit of Duane Eddy’s entire

career.

Although the next single, ‘Kommotion’, released in

August 1960, only went to #78 where ‘Because They’re Young’ reached #4, I

would insist that in a perfect world those numbers should be reversed — for

one thing, the use of strings on this

instrumental is nothing short of breathtaking, as opposed to the highly

conventional orchestration of the movie tune. Here, the guitar is holding an

actual dialog with the strings (trialog

if you throw in the hyper-active saxophone, which simply refuses to shut up

and go away even after it’s had its mid-section spotlight), and in between

the three, they really create a busy atmosphere of hustlin’ and bustlin’, with

the guitar as a fat old bumble-bee flying around its business on the lawn and

the strings as a herd of dragonflies flanging the bumble-bee from all sides.

It’s fast, fun, unpredictable, and creative as heck, easily the best song of the year to come out

of the Eddy-Hazlewood workshop. The slower, bluesier ‘Theme For Moon

Children’ on the B-side is also a somewhat weird combination of stinging

blues-rock guitar and odd orchestration that regularly fluctuates between

generic sentimental Hollywood and proto-psychedelic Eastern vibes — just wait

past the deceptive quasi-Tchaikovsky opening and you’re in for another

creative and puzzling arrangement.

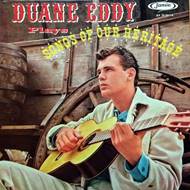

All of this preludial information is important to

understand just how serious a contrast all of that single-oriented activity

makes with Duane Eddy’s fourth LP (and, temporarily, the last to be produced

as a collaboration with Hazlewood). Fans were most likely expecting another

collection of danceable twang-guitar instrumentals; but Duane and Lee had

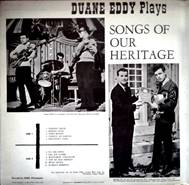

something completely different in store for them. Not only does Songs Of Our Heritage consist

completely of «oldies», reimagined and rearranged in accordance with the

artists’ more «contemporary» vision — but it also bypasses Eddy’s usual

twangy formula, instead featuring the artist almost entirely switch to

acoustic guitar and... uh, banjo? Really?

It is this initial impression, I suppose, that is

responsible for the album being almost completely bypassed and disregarded in

the (already seriously overlooked) Duane Eddy discography as a whole. As in,

who would ever want to hear Duane Eddy raising banjo hell on ‘Cripple Creek’,

or leading us in an ultra-slow, pensive, gently picked acoustic rendition of

‘On Top Of Old Smokey’? Isn’t that, like, Pete Seeger’s turf or something? We

thought we were in Phoenix, Arizona; why are we in Greenwich Village all of a

sudden? And why the hell are more than half of the songs featuring Jim Horn

on flute rather than saxophone?

("Apparently flute is a big part

of our heritage", cynically comments one of the mini-reviewers on

RYM).

Needless to say, upon my first listen to the record

I was tempted to dismiss it for good as one of those failed experiments in

«broadening one’s horizons» that so frequently mar the careers of solid

one-dimensional artists who are incapable of working outside an established

formula, but occasionally try to do so just to confirm the rule. But then I

thought, well, it is still a Lee

Hazlewood production, and Lee Hazlewood is not really one of the guys with a

generic and conventional approach to everything he does — surely there must

be something special about these

arrangements. And subsequent listens proved that there is indeed; you just

have to let it sink in, soak up, and settle down. It doesn’t hurt, either, to

actually pay attention to at least a few of the tracks instead of just

letting them serve as background music for chores, which, I think, is

precisely how most people who ever put this album on must have always treated

them.

As a typical example, take Eddy’s and Hazlewood’s

arrangement of the traditional ‘In The Pines’, which most of us probably know

as Nirvana’s ‘Where Did You Sleep Last Night?’ prior to checking out

Leadbelly’s version. It begins with a somber one-note bass riff and an

equally ominous circular little melody played by the flute, before plunging

into the main melody, lazily picked by Eddy on the banjo and echoed by a

minimalistic vibraphone part, whose lightness complements the darkness of

the bass. After one verse, the banjo melody is taken over by the flute, while

the bass suddenly switches from slow one-note pinging to a frenzied circular

run — echoing the flute opening of the song. Then, for the third verse, you have the main melody

switching over to formerly silent acoustic guitar, while the banjo recedes

into the background, the bass reverts to minimalistic pinging, and the flute

reprises the circular waltzing (!). Finally, for the last verse it’s back to

banjo, with the flute and vibraphone saying their own subtle goodbyes as

well. And it’s all over in about two minutes.

It would probably be a bit of a stretch to call this

a true masterpiece of creative arrangement, but the very fact that there is

so much going on shows that Songs Of

Our Heritage is not to be taken lightly. It may be so that people expect

Duane Eddy to show his virtuoso technique of playing acoustic guitar (and

banjo?), and leave disappointed when they find out he is not exactly Jimmy

Page; but that is a mistaken way of assessing the LP, which should instead be

held to the same type of standard as, say, Pet Sounds — a creative, wholesome product of musical

reinterpretation and arrangement. All of Duane’s classic records should, in

fact, be viewed as the product of collective

rather than individual work, but Songs Of Our Heritage most of all —

on here, the flute, the bass, the keyboards, and the string instruments are

all equi-important parts of a single whole, masterminded by the quietly

burgeoning genius of Mr. Hazlewood.

I shall not go into comparable details on the other

songs, because Hazlewood’s formula of using banjo, acoustic guitar,

vibraphone, flute, and melodic bass remains more or less consistent

throughout, and he uses comparable tricks for most of these old chestnuts, be

they fast or slow, playful or melancholic, technically challenging or

minimalistic — but since there is enough mood variety between the tracks, the

record never becomes boring once you’ve figured out the key to appreciating

it. Extensive commentary on ‘Cripple Creek’ or ‘John Henry’ is simply not

required, because the basic melodies remain the same — this is indeed a

celebration of the heritage, not a deconstruction of it — but the way they

are treated is creative and fresh, and in some departments, unique; at the

very least, I would much rather listen to this for the rest of my life than

The Kingston Trio or The Weavers, thank you very much.

The bottomline, though, is that Songs Of Our Heritage should rather be recommended for big fans

of Lee Hazlewood rather than those of Duane Eddy — regardless of the humble

liner notes by Lee and Lester Still, whose purpose almost seems to be to

dissipate certain doubts that fans could have about the nature of the record

("we have been asked many times...

‘what is Duane Eddy really like?’... this album will perhaps answer part of

the question... it shows the quiet... sometimes lonely... often beautiful...

and most certainly talented touch... of this young man"). The one

sentence from these notes that most definitely still holds true today the

same way it held true back in 1960 is "This is the ‘Duane’ that less than a dozen people know".

Here’s hoping that this review might go a little way toward rectifying this

undeserved situation — even if I would be the first to admit that even the

fully recognized prettiness and originality of these arrangements might not

be enough to elevate them to any sort of awesome-cathartic status.

Note that the album has, in recent years, been

finally re-released several times on CD; some versions include a bunch of

alternate takes for some of the songs as bonus tracks, but there is also an

excellent European release that includes some of the 1960 singles instead

(e.g. ‘Kommotion’), and, most importantly, the hard-to-find single credited

to Duane Eddy And His Orchestra and containing two songs written by Hazlewood

for the poorly remembered and artistically insignificant (but socially relevant)

low budget movie Why Must I Die?.

Of these, ‘The Girl On Death Row’ is a particularly stunning highlight:

because it is officially credited to Duane Eddy, there is some misinformation

on the Web that it is a rare example of Eddy’s vocals, but, in fact, this is

the earliest example of a vocal part as sung by Lee Hazlewood in person (and

it quite expressly says so on top of the record itself!). Not only that, but

it is clearly an important milestone in the development of what might be

known as the «Gothic Western» style — Eddy’s brief twang in the intro and

outro is downright threatening, Lee’s vocals are deeply mournful, the strings

rise and fall in a deeply agitated manner, and the lyrics, reflecting the

plot of the movie, are quite a bit chilling ("her eyes were once so full of dreams / her young heart filled with

lover schemes / now every second she must borrow / they take her life

tomorrow"). Quite a symbolic career beginning for the father of

«cowboy psychedelia» — and a rather natural early predecessor for later moody

masterpieces such as ‘Some Velvet Morning’.

|

![]()