|

The

catch here is that Neil McCormick, like most people, would probably agree that much, if not most,

of Elvis’ career in the Sixties represented a gradual slide into corniness,

self-parody, and irrelevance — and since any such slide has to have a

reasonable starting point somewhere,

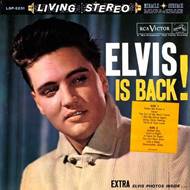

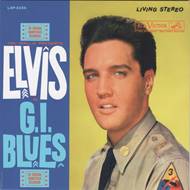

would he really draw a massive dividing line between Elvis Is Back! — an alleged «masterpiece» — and whatever came after it, starting with, say, G.I. Blues? It is not really an issue

of «good» or «bad»; it is an issue of changing musical values, of setting

upon a different path of development which may, one day, lead to artistic

bliss or complete artistic breakdown. I certainly like Elvis Is Back! quite a bit, but I could never bestow the title of

«masterpiece» upon it (at least, provided we’re only allowed one masterpiece) precisely because

this is where the seeds of Elvis’ impending decline are sown for all to see;

and the recent retrospective drive to upgrade its status to VIP level seems

rather telling for an age that shows more and more propensity for branding

the «tepidly mediocre» in pop culture as the new «emotionally exciting».

In

reality, Elvis — or, perhaps, «The Elvis Machine», as would be appropriate to

refer to the artistic world of Elvis by that time — was no more exempt from

the «Fifties’ Curse» than any of his contemporaries: having already once invented his own rules of the

game, he had no inclination or stimulus whatsoever to try and change the

rules one more time. But that was only one part of the story — had it just

been the «Fifties’ Curse», we might have seen Elvis churning out pale

inferior shadows of ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ and ‘Hound Dog’ throughout the decade,

the same way Chuck Berry and Gene Vincent did, for instance. The other part of the story, of course,

was that Elvis was King, and as King, he had certain moral obligations to his

nation — for instance, the obligation to grow up from Teenager to Man,

setting up a proper «maturity example» for the millions of young Americans

remaining in dire need of a role model. At least Chuck Berry and Gene Vincent

were totally free of any such obligations; Elvis was not. Had he married an

underage cousin or something like that, God would probably have spared him

any further embarrassments. But he was a «good boy» — too good for his own

sake, perhaps.

I

am not entirely sure when people started entertaining the actual idea that

"Elvis ‘died’ in the Army"

(which, if I am not mistaken, stems from a John Lennon quotation from one of

his interviews). Certainly legions of fans, both in America and across the

Atlantic, were impatiently waiting for the god of rock’n’roll to come back

and provide them with a new flow of energetic classics — and the small amount

of stuff that Elvis recorded while on furlough, such as ‘I Got Stung’ and ‘A

Big Hunk O’ Love’, was definitely promising, showing the exact same kind of

rock’n’roll bite as most of his 1950s RCA output. Just how many people were

seriously disappointed with Elvis Is

Back! and its surrounding singles such as ‘Stuck On You’ at the time of

release is something we’ll never know — but I think it would be a fair guess

that John Lennon, for instance, was not impressed, or else the whole "dying in the Army" thing wouldn’t

have become a thing.

Of

course, there is no impenetrable iron curtain that separates Elvis Is Back! from its predecessors.

Elvis had already recorded plenty of pop songs and sentimental ballads

before; and while there is not really even a single straightforward

rock’n’roll song à la ‘Blue

Suede Shoes’ on this record, it does feature a small bunch of grittier

numbers in a bluesy vein (‘Like A Baby’ and ‘Reconsider Baby’, above all)

which could easily appeal to a demanding musical taste (at least, back at the

time). There is no single ‘Da Ya Think I’m Sexy?’ kind of moment here where

the artist crosses a very specific artistic border that separates the likes of

«erotic modeling» from «pornography». But there is clearly a focused

intention to show the world a ‘new’ Elvis, one who has left the style of

‘Blue Suede Shoes’ and ‘Hound Dog’ behind because it is clearly embarrassing

for anybody over 25 years old to sing the likes of ‘Hound Dog’ — particularly

for a King.

All

of this is already clearly illustrated with ‘Stuck On You’, Elvis’ first

officially released post-Army single that predated the LP by a couple of

weeks. On one hand, ‘Stuck On You’ is a disappointment — it is a relatively

quiet, unhurried, blues-poppy creation from the brain of Aaron Schroeder,

nowhere near the maniacal level of noise and energy that was ‘I Got Stung’,

written by the same guy and recorded less than two years ago. On the other

hand, it’s not as if Elvis had never done well-received blues-poppy material

like ‘Stuck On You’ before — there is nothing that would make it

intrinsically worse than, say, ‘Don’t Be Cruel’ or ‘Paralyzed’. It’s got the

self-assured macho attitude a-plenty, too, and a super-tight Nashville

backing with all of Elvis’ great sidemen involved (Scotty Moore, Hank

Garland, Floyd Cramer, you name ’em), and the Jordanaires return for their

usual role of Resplendent Retinue (gotta love how they «open the doors» for

the main vocal hook at the end of each verse, right?). It’s a pretty damn

good song — just maybe not the kind

of song that Elvis’ most loyal and steadfast fans would expect him to

announce his comeback with.

The

real bad news of March 23, 1960,

was the B-side: ‘Fame And Fortune’, a thoroughly formulaic doo-wop ballad

from the embarrassingly lazy hands of the Fred Wise / Ben Weisman team, is

the first and the most typical representative of the «tepid Elvis ballad» for

the upcoming decade. Take something in a similar style from just a few years

back — say, ‘I Need You So’ from Loving

You — play the two tracks back-to-back a couple of times, and the meaning

of the word «sanitized» shall crystallize right before your eyes, clear as

day. In the place of a rougher, rawer style as practiced not just by Elvis,

but by his entire band, we have a professional, tight arrangement where

everybody quietly keeps to their own business, not allowing themselves any freedom; and in the place of a

singer who once captivated his audiences by breaking all the «rules of

decency» even while singing sentimental love ballads is an equally tightly

disciplined crooner, whose voice feels more oriented at middle-aged ladies in

a Las Vegas casino than a hormone-addled teenager. (Far be it from me, of

course, to discriminate one of these target groups over another — but it does go without saying that

boundary-breaking art has more often been created when trying to pander to

hormone-addled teenagers than to middle-aged ladies in Las Vegas casinos.) At

least ‘Stuck On You’ was a bouncy, catchy, well-written pop song; ‘Fame And

Fortune’ is one of those throwaway compositions whose value is completely

dependent on the style of delivery — and this particular style, wallowing in

its own so-called «maturity», pretty much spells out an extended death

sentence for the musical career of Elvis Presley.

The

actual LP, recorded during the same late March / early April sessions in

Nashville as the single, is fully consistent with the promise of its A- and

B-sides — typically alternating between fun, catchy pop songs and crooning

ballads, all tied together with this new, tightly disciplined and restrained

sound from everybody involved. A small part of the blame could perhaps be

placed on Chet Atkins, the great Nashville discipliner, as co-producer, but

let’s not pin everything on the

alleged Nashville strictness: ‘A Big Hunk O’ Love’ was also cut at Nashville,

and somehow managed to combine tightness with maniacal excitement. The

bottomline is that if you really want to get wild in Nashville, you can get wild in Nashville; it’s just

that in April 1960, nobody wanted to get wild in Nashville.

Arguably

the only small echo of that old wildness comes out with ‘Dirty, Dirty

Feeling’, a very short Coasters-style pop-rock number (with Boots Randolph

providing the obligatory yakety-sax backing throughout) which, not

surprisingly, comes from the remains of the old Leiber-Stoller stock

(although Colonel Parker would keep those guys away from Elvis, he apparently

did not have a serious problem with Elvis revisiting the old archives). It’s

very lightweight, nothing particularly special, but it’s got a fast tempo, a

pretty demonic, out-of-control guitar break (probably Hank Garland rather

than Scotty), and such a high-pitched, frenetic delivery from Elvis that you

could honestly mistake this for a recording from circa 1957-58, probably the

only such case on the entire album.

Alas,

much more typical here are songs

like the opening ‘Make Me Know It’, a rather average piece from the usually

reliable Otis Blackwell which should

be working along the same lines as a ‘Treat Me Nice’, but actually does not,

and what kills it is, once again, the lack of rawness — everything is tight

as a button, and what once used to be a lively, nervous, hiccupy,

unpredictable vocal style has turned into a self-assured, evenly paced,

«adult» delivery. The vocal timbre, the phrasing, the pacing, all of that is

still unmistakably and uniquely Elvis, but the difference is that just a few

years ago he and his band could elevate a generic pop throwaway to the status

of a classic; in 1960, in order to be truly memorable, a song on an Elvis

album had to have at least a pinch of compositional genius — otherwise, you

ended up with this middle-of-the-road stuff like ‘Make Me Know It’, which

sounds kinda cool while it’s on and then goes out the window immediately.

By

contrast, it is hardly possible to forget ‘Fever’, yet this is largely

because most of the creative work on that song had already been done by Peggy

Lee (the original

version, released by the somewhat obscure R&B singer Little Willie

John, was OK, but clearly it was Peggy Lee who really brought to light all of

the song’s unique potential with that bass-’n’-percussion arrangement and

all). With its glitzy-sensual reputation and all, ‘Fever’ is a number which

is probably very hard to be taken not

tongue-in-cheek in the modern day and age (even I have to confess that

‘Fever’ works best with the

Muppets), but at least it is a good showcase for Elvis’ new-found

«maturity»: Peggy Lee may have found the perfect way to make the song work

and turn it into something unique, but it took Elvis to really bring a

«feverish» aspect to the singing — it’s not just the deep tone, it’s the wobble in the voice that matters. It

is Elvis’ most theatrical delivery on the entire album, and also one that, I

think, he would be incapable of earlier (although a few of these dramatic

elements in his voice do crop up as early as the Sun era — see ‘Blue Moon’

and suchlike), which kind of makes me wish that, perhaps, if he really cared

so much about sounding more «adult» and all, he might have simply tried to

record an entire album of vocal jazz like this.

On

the other hand, while I might be alone on this, I am not so sure of Elvis as

a great blues singer. Surprisingly,

Elvis Is Back! is capped off with

not one, but two slow blues tunes:

Jesse Stone’s ‘Like A Baby’ and Lowell Fulson’s ‘Reconsider Baby’, taken at

more or less the same tempos and given the same piano-and-sax-centered

arrangements. They’re decent, and they certainly sound a bit more

raggedy-shraggedy than the glossy pop songs on the album, and the Boots

Randolph-led two-verse jam on ‘Reconsider Baby’ is a nice boost to the entire

band... but I honestly do not see what it is exactly that Elvis’ delivery

brings to the table that was not already present in Fulson’s classic original;

besides, the song is really more like a vehicle for cool guitar soloing than

vocalizing, so I’d rather listen to people like Eric Clapton covering it than

Elvis. Now it goes without saying that hearing Elvis rock out on a slow blues

jam with his Nashville buddies is a way

better proposition than hearing him do his Vegas stuff; but even so, this cat was born to give chicks

‘Fever’, not waste his time on blues triplets. Mick Jagger could give the

blues a new voice; Elvis really couldn’t.

(Important

correction, however: he could give a pretty damn solid voice to «blues-pop» —

‘A Mess Of Blues’, recorded during the same sessions and later released as

the B-side to ‘It’s Now Or Never’, is a terrific performance, but that is

because its melody and structure give Elvis a better opportunity to showcase

his trembling, vulnerable, quivers-down-my-backbone voice; he doesn’t have

that much luck with the nonchalantly threatening style of ‘Reconsider Baby’

which simply does not give him a good opportunity to play Emotional Elvis,

and who needs a non-Emotional Elvis?).

In

between the fabulous «jazz-pop» of ‘Fever’ and the somewhat less jaw-dropping

«blues-rock» of the ‘Baby’ songs, we largely find what we expected to find —

pop ditties and crooner ballads, some a bit nicer than others, but none

really matching the strength and freshness of what used to be. Tired old

chord sequences married to tightly predictable Nashville arrangements and

well-disciplined, but not tremendously exciting vocal arrangements — listen

to something like ‘Soldier Boy’ and you’ll hear all of Elvis’ tried-and-true

vocal tricks, but restrained this

time, as if he were simply too afraid to wake up the neighbors or something.

Of all this remaining stuff, my personal favorite is probably a cover of the

Drifters’ ‘Such A Night’ — Elvis’ loving tributes to Clyde McPhatter are

always adorable, and at least this one here’s a real naughty one,

particularly the ending, which horndog Elvis and his «slutty» Jordanaires

retinue somehow manage to turn into the dirtiest bit of moaning on record

since Ray Charles’ ‘What’d I Say’ (I made sure to revisit the original

Drifters recording and, sure enough, there was nothing like that set of ecstatic oohs and aahs in Clyde

McPhatter’s coda).

On

the whole, as you can already tell, Elvis

Is Back! is quite a bit of a mess. In a way, Elvis’ post-Army career is

not so much «flat-out awful» as it is frustratingly intriguing — few artists

had the same mix of highs and lows for such a long time, a Jekyll-and-Hyde

sort of thing going on where sometimes Man temporarily triumphs over Machine,

but more often it is the Machine that engulfs and enslaves the Man, and the

end is always tragic. Here, we see the beginning of the process where Man and

Machine sort of work in tandem, with a seemingly mutually beneficial

compromise whose consequences, however, in the not-so-long run shall be as

strictly determinant as those of the Munich Agreement. In any case, there is

no sin in liking this record, in singing along to even its sappiest bits,

even in thinking that ‘Reconsider Baby’ is a truly great piece of slow blues

if you so desire. There is, however — returning full circle to the quotation

at the beginning of the review — something deeply wrong in overrating this

record, daring to call it a «masterpiece» and thus insinuate that somehow, it

embodies genuine, if not monumental, artistic progress for Elvis compared to

his pre-Army years. Statements like these basically put an equality sign

between the type of art that dashingly challenges formula and the one that

largely conforms to its rules, which I find deeply unjust. (It is true that

«challenging formula» is not the only necessary condition for great art, but,

fortunately, Elvis had no problems satisfying all those conditions in the

Fifties).

Case

in point: my favorite track on the expanded CD edition of the album has

always been ‘I Gotta Know’, the B-side to the boring ballad ‘Are You Lonesome

Tonight?’ released late in 1960, but also recorded at the same sessions. The

song, written by Paul Evans and originally recorded by Cliff Richard in a

more countrified version, is given an absolutely perfect pop arrangement

here, catchy as hell and featuring brilliant vocal harmonizing between Elvis

and the Jordanaires. The drums, the bass, the piano, the slightly sratchy

weave of the rhythm guitar, the perfect choreography of the backing vocals —

it’s like a geometrically precise rococo construction without a single flaw

in the complex design; even a next-generation popmeister like Paul McCartney

would have a hard time topping something like this. But if I had to choose

between ‘I Gotta Know’ and something, like, say, ‘Milkcow Blues Boogie’?

(It’s a good thing I don’t). It’s not an issue of «pop» versus «rock», mind

you; it’s more an issue of inspiration versus perspiration, of ecstasy versus

craft, all of the good and evil of which can be found in «pop», «rock»,

«blues», «jazz», whatever label the algorithm sticks on it.

That

said, I do not want to make it seem as if «craft» and «perspiration» by

themselves are necessarily a bad thing, even if the balance of powers is

completely overthrown and all the good cards are on their side. It is, after

all, quite possible that, had Elvis had the strength to resist the Machine

and stubbornly stuck to his rock’n’roll formula, all he would be capable of

would be mediocre self-plagiarism (like, indeed, most of the stuff that Chuck

Berry did in his post-Fifties career); there is little reason to argue that,

if not for Colonel Parker and the rest of the Memphis Mafia, Elvis’ career

would have flourished (although it is true that he would probably spend less

time on his stupid movies). His submissive placing himself in the hands of

«professionals» did bring on mixed results, but said «professionals» weren’t

exactly mindless, soulless, heartless automatons — accusing the Nashville

session players of not loving music or not understanding its purpose would be

totally ridiculous. What they could

be accused of is a lack of ambitions: for most of those guys, music was there

to entertain people, giving them what they already want rather than

suggesting there might be something else

out there. The entire point of Elvis’ «maturity» was to subscribe to that

philosophy — a subscription fully and completely responsible for both his

high and low points from now on, and, ultimately, for August 16, 1977.

|

![]()