|

Let’s take a

look at John Marlo’s original liner notes: "She was just a little girl of 17 who had high hopes and big dreams...

the pert teenager sat down at the piano to set down the melody in her heart.

It came quickly, almost effortlessly. Fate stepped in. An A&R executive

heard the tune, liked it, and liked the singer better. The singer? Same as

the writer. They rushed out a record. It was an immediate smash. Yes, a

youngster named Etta James had just written and recorded one of the great rock’n’roll

standards of all time... ‘Dance With Me, Henry!’"

Sounds cool,

right? Inspiring and all? Except that most of it is bullshit. First and

foremost, the track titled ‘Dance With Me, Henry’, included on this LP as the

lead-in number, is actually a recording from 1958, not 1955, when Etta was

already a young lady of 20. Second, considering the actual lyrics, the song

would formally be a cover version of ‘Dance With Me, Henry’

by Georgia Gibbs — that one was

actually released in 1955. So did Etta steal the song? No, of course not;

Georgia’s version was, indeed, in itself a «verbally sanitized» cover of

Etta’s ‘Roll With Me, Henry’, her first single for Modern, which was actually released in 1955, when

"she was just a little girl of 17", did become an immediate smash on the R&B charts, staying on

top for about a month, and also had to sport a fake title of ‘The Wallflower’

because, apparently, «roll with me» was considered inappropriate, though, honestly,

the song was all about just dancing from the very beginning.

So the liner

notes are not that wrong, right?

Marlo simply messed up the original recording with the slightly «tamer»

re-recording from three years later (probably intentionally — in 1961, the

conservative backlash against indecency in popular music was at its peak, and

Crown Records did not want to take unnecessary risks). But no, it gets worse.

The "pert teenager" never really "sat down at the piano"

to compose ‘Roll With Me, Henry’ for the simple reason that the melody of

‘Roll With Me, Henry’ was written at least a year earlier — by Mr. Hank

Ballard, whose ‘Work

With Me, Annie’ had been an even bigger hit in early 1954. ‘Roll With Me,

Henry’ was a transparent answer to ‘Work With Me, Annie’ (as is glaringly

obvious even from the rhythmic correlation of both titles), co-credited to

Etta with her discoverer and promoter, Johnny Otis, so it is not even clear

who of the two had the actual idea to latch on to Hank Ballard’s hit or came

up with the new lyrics. Even in 1961, I think, when public memories of big

hits from 1954–1955 were a little fresher than they are today, it would not

take much to expose the phoney character of the liner notes; and today,

although that age is quite a bit more removed, we have the benefit of much

better access to information, so here’s another lesson about the importance

of double-checking.

That said, the

phoney in question here is Mr. John Marlo and certainly not Etta herself.

Back in the 1950s — and, some might argue, even beyond that — her principal

and very transparent schtick was precisely that: take those big, bold,

catchy, oh-so-masculine musical creeds pumped out by various blues, R&B,

and rock’n’roll artists, add an extra bit of magic potion, and get them to

transition into big, bold, catchy, oh-so-feminist musical creeds of her own.

Although other female artists at the same time occasionally pulled such

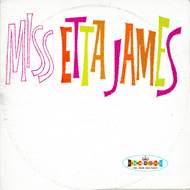

stunts as well, listening to both the songs included on Miss Etta James and the rest of her A- and B-sides from the same

period shows that nobody was doing this on such a rigorously consistent

basis. In sheer musical terms, our lady does nothing much here but steal,

steal, steal — from Muddy Waters, from Little Richard, from various doo-wop

artists whose names escape me because doo-wop is so not my thing — yet there

is always a valid point to all this material being so second-hand derivative:

she is literally translating all these songs from «man-speech» to

«woman-speech», which will never make them (like any translations) equally

valuable to the originals, but makes them perfectly enjoyable if you can

appreciate the pragmatics of the act and admire the passion displayed within.

As long as we refuse to buy the «17-year

old prodigy sitting down at the piano to create musical masterpieces» myth

that not-too-honest people tried to attach to this aesthetics, I think we can

enjoy the ride for all it’s worth.

Regardless of

its origins, ‘The Wallflower’,

a.k.a. ‘Roll With Me Henry’ (not

included on this LP), is a lot of fun, with Etta pulling off a fairly

convincing Ruth Brown impersonation — at 17, she did not yet have the time to

fully work out her own identity, but she did show enough confidence and

sassiness to roll along with the finest voices in contemporary R&B. (The

opening male vocals, by the way, come courtesy of Richard Berry, the author

of ‘Louie Louie’). I think that to most modern listeners, the song will be

primarily recognizable as a sympathetic piece of nostalgic proto-rock’n’roll

by way of Back To The Future, but

in 1955 it was, of course, all about role reversal — all through the Fifties,

Etta’s main calling was to show that gals can hold their own against guys,

and this is, naturally, where it all starts.

Because of the song turning into such a monster hit, it was inevitable

that Etta would revisit its theme at least several times throughout her Modern

career. Three years later, she did indeed revive the song once again under

its «censored» title of ‘Dance With Me, Henry’; ironically, though, from a musical standpoint the 1958 edition

was much wilder than the original (and certainly a hella lot wilder than the

cutesy Georgia Gibbs cover). It’s faster; it completely drops the male vocal

counterpart, so that it could be Etta’s show all the way; it features a much

more aggressive, barking and growling vocal delivery; and it has some

maniacal Little Richard-like sax solos to boot. If you want to make a quick audio

demonstration to somebody on what was the actual difference between «R&B»

and «rock’n’roll» in the 1950s, just play these two versions back to back... and

no verbal explanations are necessary. (The LP also includes ‘Hey Henry’, a

direct sequel to ‘Roll With Me Henry’ with another call-and-response session

between Etta and Berry — this one at least has a tiny bit of melodic

variation on the original rather than just adding yet another set of lyrics).

Unfortunately, Etta’s early winning streak did not last long. Running on

the strength of the momentum, her next single, ‘Good Rockin’ Daddy’, still

managed to climb to #6 on the R&B charts — written by Berry, it was

basically a piece of Muddy Waters-style mid-tempo Chicago blues transposed to

a danceable R&B setting, and another solid showcase for Etta’s vocal

confidence, but it just didn’t have the seductive aspect of ‘Henry’, and

besides, that accent on the second beat just doesn’t make you want to dance nearly as much as when it’s on the

first one, you know? The «lesson» was not learned, however, and the third

single was even slower and Chicago-er: ‘W-O-M-A-N’ was Etta’s intrusive

contribution to the Muddy Waters / Bo Diddley masculinity contest of ‘Hoochie

Coochie Man’, ‘I’m A Man’, and ‘Mannish Boy’. All about role reversal once

again, but the public didn’t really get it — some might say due to sexism,

others might point out that the buyers simply had had enough of the ‘Hoochie Coochie

Man’ riff in their lives. However, the other side of the single was ‘That’s All’,

a driving piece of rock’n’roll from sax player Maxwell Davis whose roots

clearly lie in the jump blues of ‘Good Rockin’ Tonight’ but whose level of

power and energy is about as top level as 1955 technically permitted anyone. With

a message as simple, punchy, and cockily delivered as "all you gotta do is rock and roll and that’s

all", the fact that this one did not sell is, if not a travesty,

then at least a curiosity.

And with that, it was all over for Etta at Modern — over the next three

years, the label let her put out 7-8 additional singles, none of which made any chart impact, as if the world was strictly

determined to have the artist remembered exclusively for ‘Roll With Me Henry’

and nothing else. This was an odd decision on the world’s part. For sure, all of these singles — no exceptions —

would continue to be highly derivative of other people’s work, running mostly

on the fire within Etta’s soul, throat, and loins, rather than on any kind of

original ideas. But this was precisely the situation with ‘Henry’ itself, and

the fact that it was merely a reinvention of ‘Work With Me, Annie’ did not

stop people from appreciating it. There certainly is an element of lucky

randomness here, which is a little frustrating.

Personally, having significantly expanded the original 10-track release

with at least 12 more recordings from the same era, I find the resulting

mega-collection of Etta’s recordings for Modern every bit as enjoyable as any

Ruth Brown or LaVern Baker record from the same era, to name just a few of

the top female R&B artists. Etta was really willing to try out anything

to succeed: we have slow, luscious blues ballads with a doo-wop flavor (‘Do Something

Crazy’; ‘I Hope You’re Satisfied’), playful reinterpretations of Muddy Waters

(‘My One And Only’, an easily recognizable variation on ‘Feel So Good’), poppier

takes on Chuck Berry (‘Strange Things Happening’, basically a fluffier

rewrite of ‘Thirty Days’), and lots and lots and lots of girl-perspective

takes on Little Richard. Blues, R&B, rock and roll, doo-wop, Latin, pure

dance pop, just about every popular genre works for Etta here — she is doing pretty

much the same thing that James Brown and the Famous Flames were doing all

through the 1950s, ready to try anything as long as it worked (and sometimes

even when it didn’t).

A particular favorite of mine from that period, unfortunately not included

on the LP, is ‘The Pick-Up’,

credited not to one, but two sax

greats from the illustrious state of Louisiana — Harold Battiste and Plas Johnson;

I do not know who of the two blows the actual sax on this track (maybe both?),

but it is a wonderful example of oh-so-New Orleanian musical humor, with Etta

holding an expressive spoken dialogue with the saxophone trying to «pick her

up». The real hero on the track is not Etta, but the saxophone, showing all

of the instrument’s emotional range in this particular case — from cockiness

and swag to moodiness and depression (once the «pick up» fails to work). It’s

a bit of a theatrical mini-masterpiece here, one of those countless inventive

nuggets from the past that all slipped through the cracks, but if you have a

couple of minutes to spare, it’s got serious potential to brighten up your

day for a while.

All in all, I would say that anybody interested in Fifties’ music from a

more sociological perspective should necessarily

give this stuff a listen — Etta here does for the male-dominated Chicago

blues and early rock’n’roll scene pretty much the same thing that Wanda Jackson

did for the rockabilly market: reverse the roles so that the ladies can take

charge, for a change. From a more strictly musical perspective, of course, this is not Etta’s best work, if

only because most of the songs are just carbon copies of other people’s

ideas. But I can also totally see how for some people this could be Etta’s

finest collection, if only because it features her so youthful, so raw, so

energetic, and without all that glossy orchestrated stuff that the people at Chess

would heap up on her from the very beginning of her tenure with the label. It’s

basically the equivalent of something like The Bangles’ self-titled EP, when

they were still a fiery punk-pop band before sacrifices had to be made for assured

mainstream success. One thing’s for certain: I would much rather "roll with Henry" than live

through "life is like a song",

and somehow I feel that back in those days, Etta would, too.

|

![]()